During the 1960s, autism was shrouded in misunderstandings and myths that have since been debunked. This article explores ten misconceptions from that era, highlighting the progress made in understanding autism as a complex neurodevelopmental condition.

By examining these outdated beliefs, we can appreciate how far we’ve come in promoting awareness, acceptance, and support for autistic individuals.

1. Autism Was Caused by Cold, Unloving Mothers

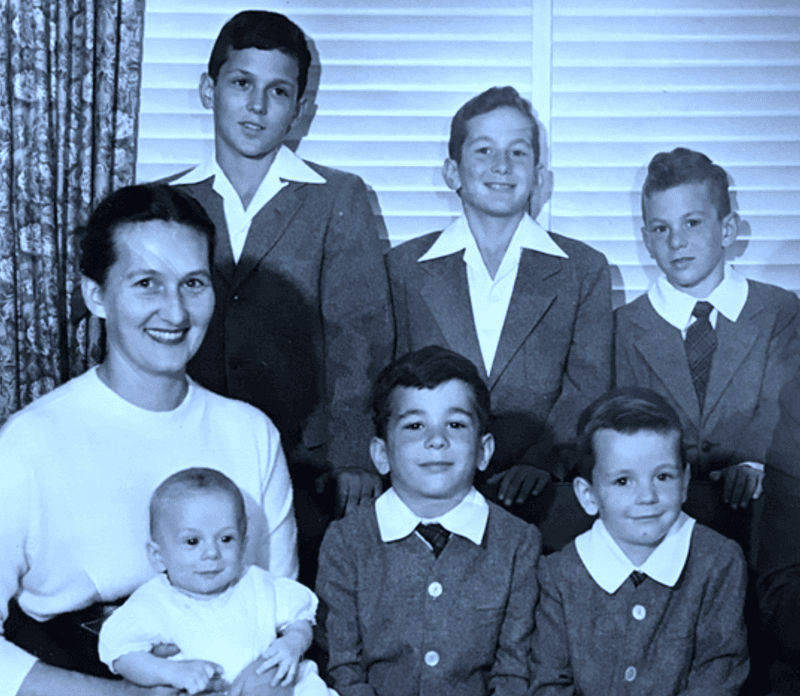

In the 1960s, a common belief was that autism stemmed from the emotional frozenness of mothers. Psychiatrist Bruno Bettelheim propagated this idea, branding these mothers as ‘refrigerator mothers’.

This theory led to feelings of guilt and blame among countless women. Today, we understand that autism is a neurodevelopmental condition with significant genetic links.

The shift from blaming mothers to recognizing the complexity of autism is monumental. Families now receive support and understanding instead of blame, showcasing a more compassionate and educated approach to autism.

2. Autism Was Rare or Practically Nonexistent

Back in the 1960s, autism was often seen as a rare condition, if acknowledged at all. Many autistic individuals were misdiagnosed with childhood schizophrenia, intellectual disabilities, or behavioral disorders.

This misconception was partly due to a lack of diagnostic criteria and awareness. Today, we recognize autism as more prevalent, thanks to refined diagnostic practices and greater awareness.

The idea that autism was ‘rare’ reflects past societal blind spots, highlighting our journey towards a more accurate understanding of neurodiversity.

3. Autistic Children Were Thought to Be Emotionally Distant

In the 1960s, autistic children were wrongly seen as emotionally detached or incapable of empathy. This stereotype painted them as unaffectionate and distant.

Modern insights reveal that autistic people experience deep emotions and empathy but may express them differently. Recognizing these unique emotional expressions enriches our understanding of autism.

We’ve moved from viewing autistic individuals as emotionally void to appreciating their diverse emotional landscapes. This shift fosters inclusivity and deeper connections within families and communities.

4. Autism Was Considered a Form of Childhood Schizophrenia

During the 1960s, autism and schizophrenia were frequently conflated in psychiatric literature. This confusion caused misdiagnoses and inappropriate treatments.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that autism was officially recognized as a distinct diagnosis in the DSM-III. Separating these conditions has allowed for tailored support and interventions.

Today, we clearly distinguish between autism and schizophrenia, providing more accurate diagnoses and care. This progression underscores the importance of ongoing research and the evolution of psychiatric understanding.

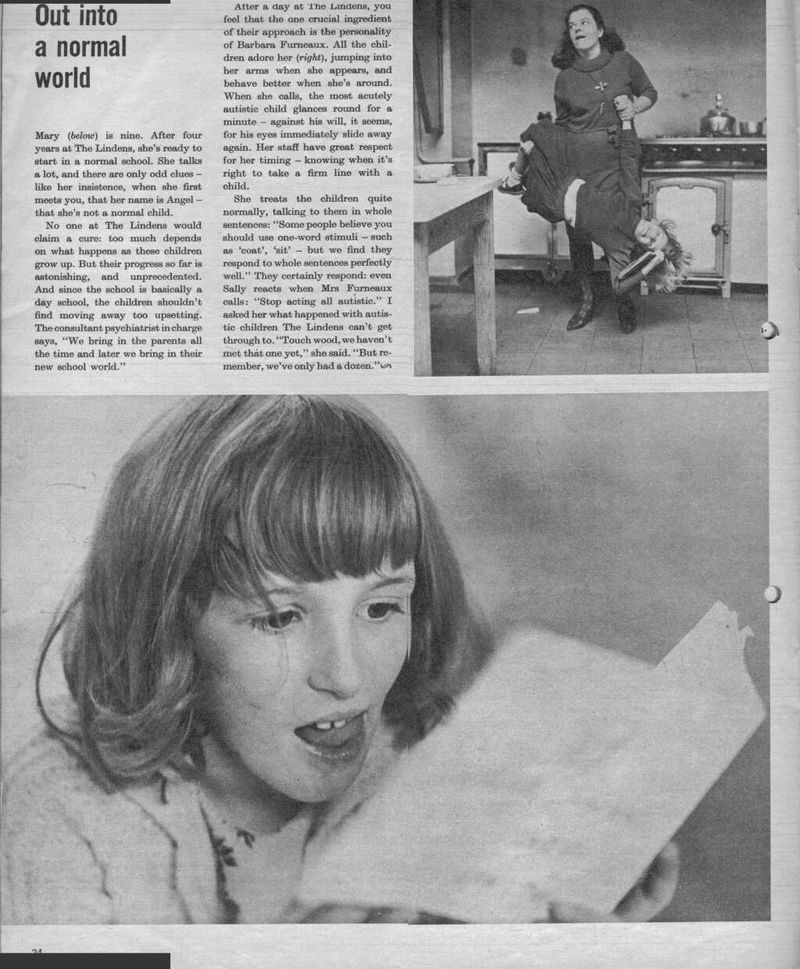

5. Autistic Individuals Could Not Learn or Thrive

In the 1960s, there was a misconception that autistic individuals couldn’t learn or succeed. Education systems often overlooked their potential, leading to inadequate support.

Today, we know autistic individuals can excel in various fields with the right support and understanding. Many make significant academic, professional, and social contributions.

This evolution reflects a broader acceptance of neurodiversity and the personalized education approaches now employed. Acknowledging their capabilities allows society to foster environments where autistic individuals can truly thrive.

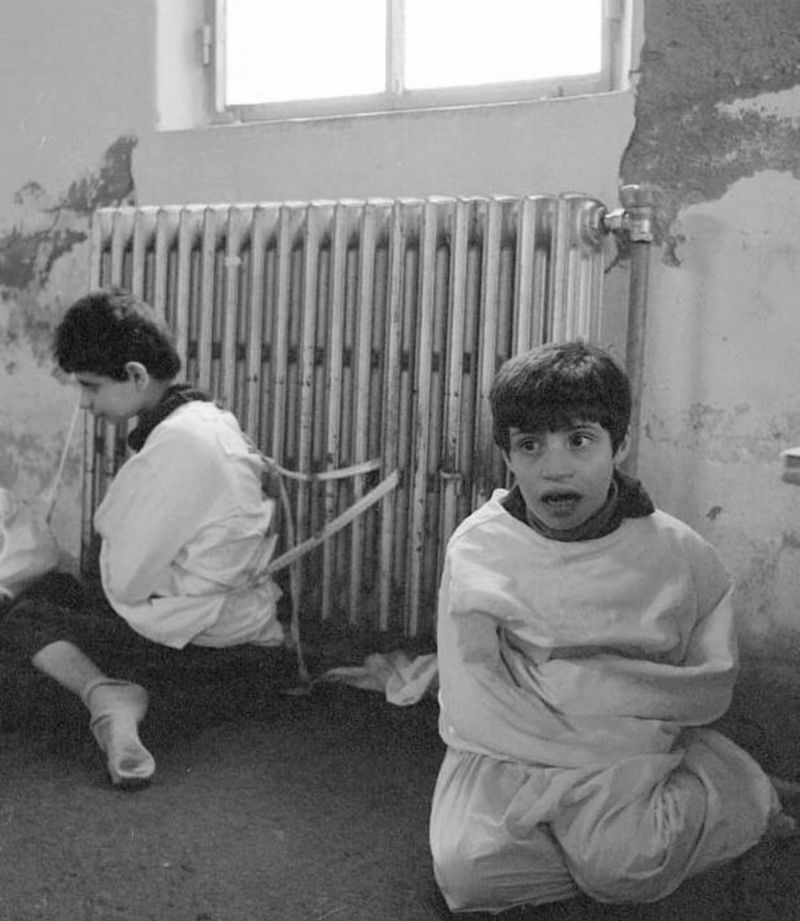

6. Institutionalization Was Often Seen as the Best Option

During the 1960s, institutionalization was often recommended for autistic children. These institutions were places of neglect and mistreatment, isolating children from family and community.

The narrative has significantly changed; today, we prioritize inclusion, community-based support, and independent living. Autistic individuals are encouraged to be part of society, with access to resources that foster independence and social integration.

This shift from isolation to inclusion marks profound progress in autism care, emphasizing dignity and respect for autistic individuals.

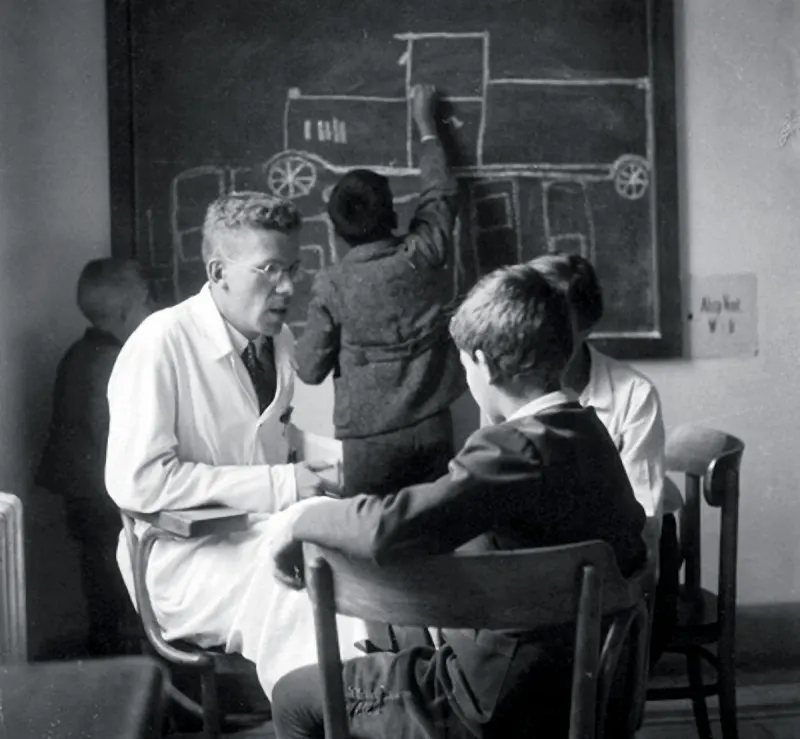

7. Autism Was Thought to Be Entirely Psychological

In the 1960s, autism was often viewed as a purely psychological issue, attributed to emotional or behavioral problems. This perspective overshadowed potential biological and neurological explanations.

Modern research has established autism’s basis in brain development and genetics. Understanding its neurological underpinnings has led to more effective interventions and support strategies.

This transition from a psychological to a neurodevelopmental viewpoint highlights strides in scientific understanding, fostering more compassionate and comprehensive care for autistic individuals.

8. Autistic Traits Were Seen as Behavioral Problems to Be “Fixed”

In the past, traits like stimming or nonverbal communication were viewed as problems needing correction. These behaviors were often punished or suppressed rather than understood.

Today, we recognize them as important aspects of autistic expression and communication. Instead of ‘fixing’ these traits, we embrace and support them, creating environments that respect neurodiverse needs.

This shift from suppression to acceptance allows autistic individuals to express themselves freely, promoting well-being and self-identity.

9. No Awareness of Autism in Girls or Women

The belief that autism predominantly affected boys led to girls being largely overlooked in diagnoses and research. This gender bias resulted in generations of missed or late diagnoses for women.

Today, we understand that autism affects all genders, though it may present differently. Efforts to recognize and diagnose autism in girls have improved, helping many receive the support they need.

Addressing these disparities marks progress in gender equity within autism research and care, ensuring all affected individuals are acknowledged and supported.

10. Autism Was Seen as All-or-Nothing

In the 1960s, autism was viewed in black-and-white terms: you either had ‘classic’ autism with severe symptoms or you were not autistic. The concept of an autism ‘spectrum’ didn’t exist.

Today, we recognize autism as a broad spectrum, encompassing a wide range of traits and abilities. This understanding allows for more personalized support and interventions, honoring the individuality of each autistic person.

Acknowledging the spectrum reflects our evolved comprehension of autism, promoting more nuanced and effective approaches to care.