Throughout American history, visionary Black women educators created vital learning spaces when segregation barred African Americans from equal education.

These determined founders established schools that transformed lives despite overwhelming obstacles of racism, sexism, and limited resources.

Their educational institutions not only survived but evolved into colleges, universities, and community centers that continue shaping minds and opening doors today.

1. Mary McLeod Bethune’s Daytona Dream

Starting with just $1.50 and faith, Mary McLeod Bethune founded her school in 1904 with five young students. She personally collected boxes, crates, and discarded items to create makeshift desks and beds.

Her tiny school for Black girls grew into Bethune-Cookman University, now a respected HBCU with thousands of students. Bethune’s philosophy combined academic excellence with character development and community service.

She famously said, “The whole world opened to me when I learned to read.” This belief fueled her lifelong mission to provide quality education to African Americans during the harsh Jim Crow era.

2. Nannie Helen Burroughs: Making the ‘Impossible’ Happen

“We specialize in the wholly impossible” wasn’t just a motto for Nannie Helen Burroughs—it was her life’s mission. Denied teaching positions despite her qualifications, she responded by creating her own educational institution in 1909.

The National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington D.C. combined vocational skills with academic rigor and spiritual development. Her revolutionary “three B’s” philosophy—Bible, bath, and broom—emphasized moral character, cleanliness, and practical skills.

While other schools focused solely on domestic training, Burroughs insisted her students learn literature, public speaking, and business management—skills that prepared them for true independence.

3. Artemisia Bowden’s Sewing Class Revolution

From a humble sewing class to a thriving college—Artemisia Bowden’s 52-year leadership transformed St. Philip’s College in San Antonio. Known as the “Angel of San Antonio,” she began teaching practical skills to Black girls in 1898 during the height of segregation.

Her determination kept the school alive through the Great Depression when she used her personal salary to pay faculty. Remarkably, she fought for and won state funding in 1942, transitioning St. Philip’s into Texas’ first public junior college for African Americans.

Today, St. Philip’s serves over 13,000 students annually as one of the oldest and most diverse community colleges in America.

4. Thyra J. Edwards: Education With Global Vision

Labor organizer, journalist, and social worker Thyra J. Edwards established her Chicago school with a revolutionary perspective. Unlike most institutions of the 1930s, her curriculum emphasized international solidarity and workers’ rights alongside traditional subjects.

Edwards brought her extensive global experience into the classroom. Having traveled to the Soviet Union, Mexico, and Europe as a labor activist, she taught her students about worldwide struggles for justice.

Her school particularly focused on preparing young Black women to be community organizers and social change agents. Though less documented than other educational pioneers, Edwards’ approach to education as a tool for social transformation remains remarkably relevant today.

5. Lucy Craft Laney’s Bold Educational Experiment

In 1883, during the dangerous post-Reconstruction era, Lucy Craft Laney boldly opened her school for Black girls in Augusta, Georgia. The daughter of former slaves and the first African American woman to receive a college degree in Georgia, Laney understood education’s transformative power.

Her Home Industrial School (later Haines Institute) broke racial barriers by offering Latin, algebra, and college preparatory courses—subjects typically denied to Black students. Against fierce opposition, she insisted African American children deserved classical education, not just vocational training.

Her school’s motto reflected her philosophy: “God has nothing to make men and women out of but boys and girls.”

6. Carrie Steele Logan: From Orphanage to Academy

As a former enslaved person working as a railroad station maid, Carrie Steele Logan noticed abandoned children sleeping in boxcars. Her compassion sparked action—she began taking these children home, eventually selling her home and publishing her autobiography to fund an orphanage in 1888.

Logan’s Freeman’s Mission Industrial School in Atlanta expanded from childcare into comprehensive education. Children received academic instruction alongside practical skills like carpentry, farming, and domestic arts.

At age 61, when most contemplate retirement, Logan embarked on her greatest work. Her institution, later known as the Carrie Steele-Pitts Home, continues serving Atlanta’s children over 130 years later—making it the oldest Black orphanage in America.

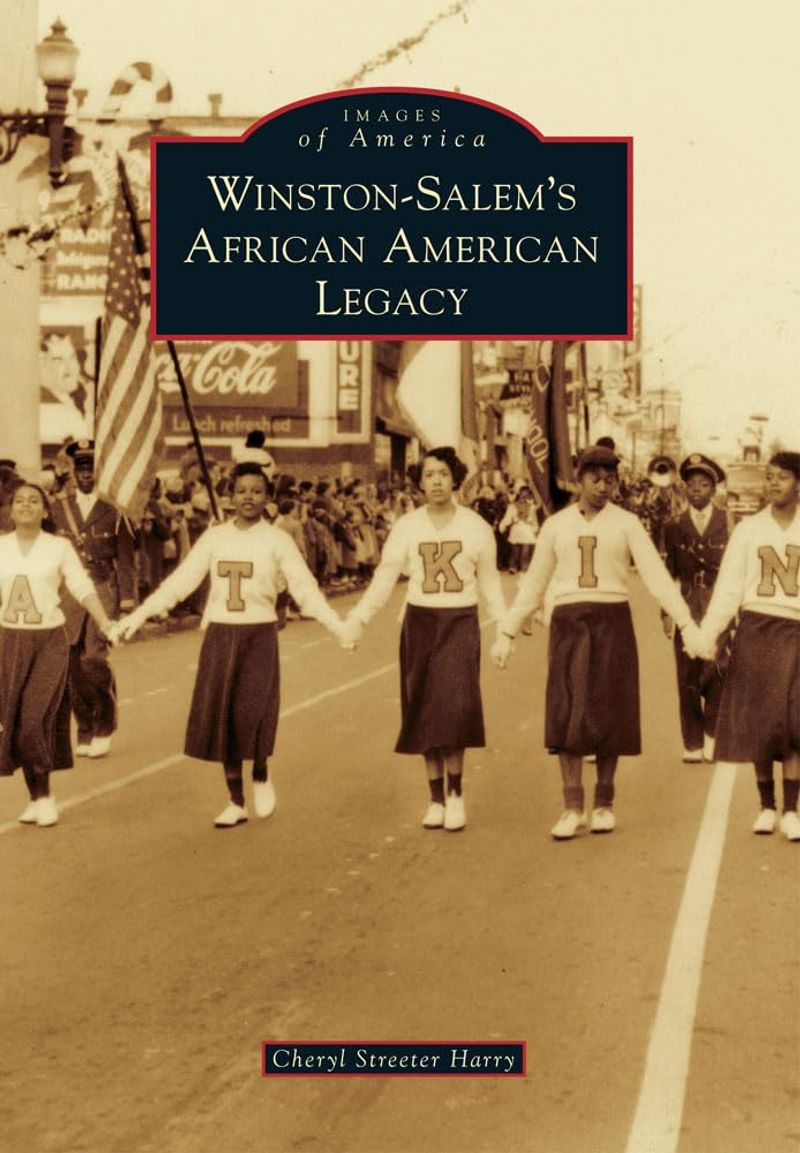

7. Winston-Salem’s Hidden Heroines

While Dr. Simon Green Atkins receives primary credit for founding Slater Industrial Academy (now Winston-Salem State University) in 1892, Black women educators formed its backbone. These unsung heroines taught classes in church basements before proper facilities existed.

Women like Ella Baker and Anna Julia Cooper served as early faculty members, developing innovative teaching methods despite severe resource limitations. Their dedication transformed a one-room schoolhouse into a thriving university that today serves over 5,000 students.

These pioneering educators insisted on teaching critical thinking alongside practical skills—a revolutionary approach during an era when many believed African Americans should receive only basic vocational training.

8. The Collective Vision of Mississippi’s Methodist Educators

The Mississippi Industrial College for Women emerged from the collective determination of African American Methodist women in the early 1900s. Unlike institutions with single founders, this school represented community organizing at its finest.

These women, whose individual names often went unrecorded in historical documents, pooled resources during an era when Black women earned pennies on the dollar compared to white men. Church basements served as first classrooms before permanent structures could be built.

Their curriculum balanced academic subjects with practical skills training, preparing young Black women for economic independence. Though the original campus no longer operates, its alumnae continued the educational mission through community programs throughout Mississippi.

9. Oseola McCarty’s Unexpected Educational Legacy

Oseola McCarty’s story flips the traditional founder narrative—she worked as a washerwoman for 75 years, saving pennies that ultimately helped sustain Piney Woods Country Life School. Though not the original founder, her $150,000 donation in 1995 (her life savings) brought national attention to this historic Mississippi institution.

McCarty never finished school herself, making her commitment to education especially poignant. Her influence extended beyond financial support—she regularly visited classrooms, showing students how determination and sacrifice could create opportunities.

Today, Piney Woods remains one of America’s four remaining historically Black boarding schools, continuing to serve rural students with limited educational access.

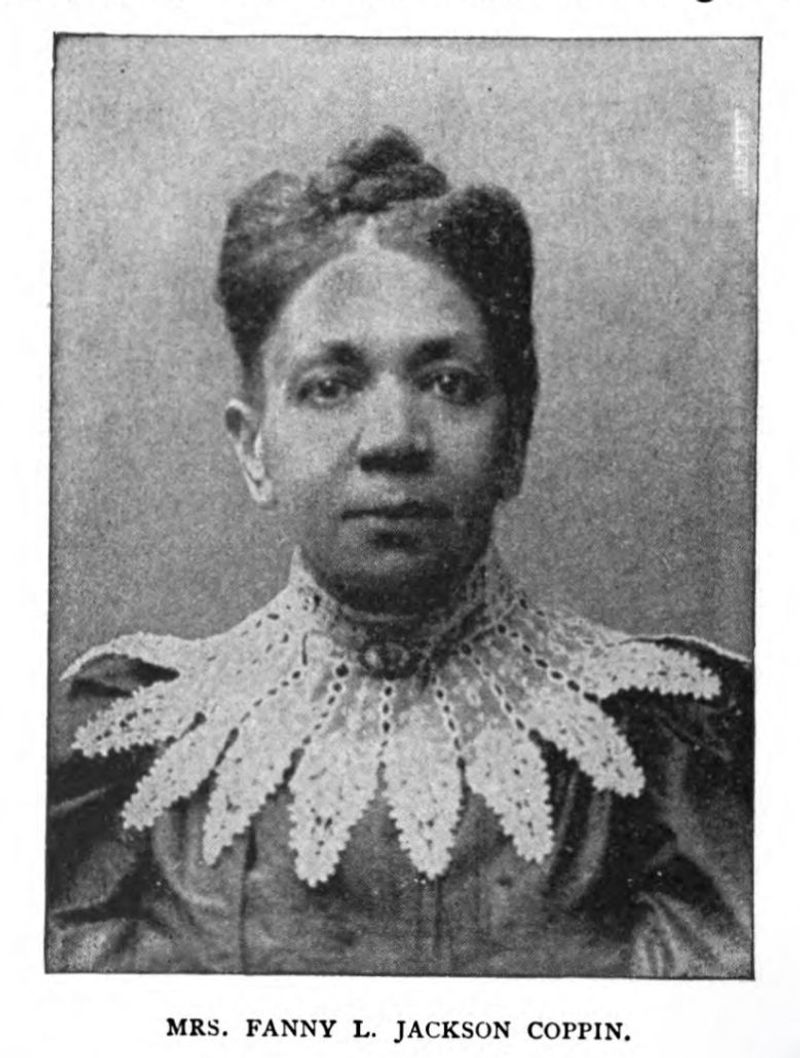

10. Fannie Jackson Coppin: From Enslavement to Educational Pioneer

Born into slavery and purchasing her own freedom at age 14, Fannie Jackson Coppin became the second African American woman to earn a college degree in the United States. Her remarkable journey led her to transform Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth in the late 1800s.

Coppin revolutionized the curriculum by adding an industrial department specifically designed for young women. She firmly believed technical skills combined with classical education would create truly independent graduates.

“Knowledge is power” wasn’t just a saying for Coppin—it was lived experience. Her educational innovations created pathways for thousands of Black women to secure employment beyond domestic service, fundamentally changing Philadelphia’s economic landscape for generations.