When King Tutankhamun took the throne at age nine, he inherited a kingdom in turmoil. His father, Akhenaten, had made radical religious changes that upset Egyptian society.

As the boy-king ruled from 1332 to 1323 BCE, his subjects lived under specific expectations that helped restore order to ancient Egypt. These rules shaped daily life for everyone from farmers to nobles.

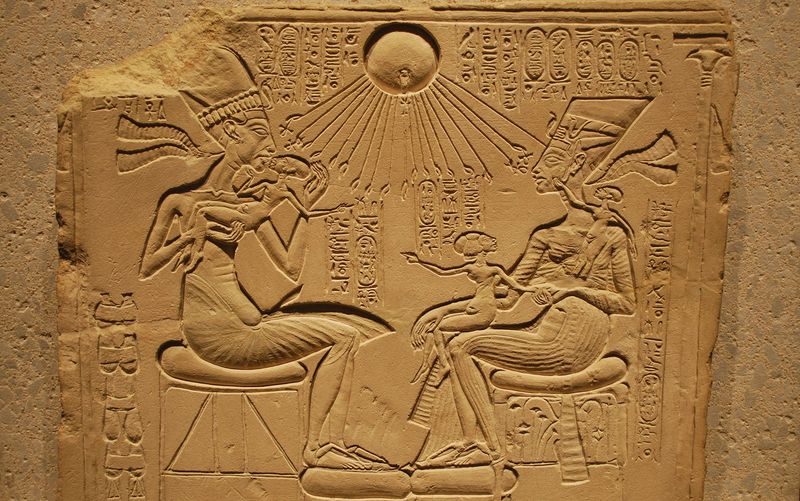

1. Worship Multiple Gods Again

The religious revolution was over. After Akhenaten forced everyone to worship only the sun disk Aten, Tutankhamun’s reign brought back the old ways. Citizens rejoiced as they could again pray to beloved deities like Amun, Osiris, and Isis. Temple doors reopened across the kingdom, with colorful processions filling streets that had grown quiet. Families returned to keeping household shrines where they left offerings for personal patron gods. Even common workers could now wear amulets of their favorite deities without fear of punishment. The familiar comfort of multiple divine protectors returned to daily life, replacing the confusing single-god system that had never truly taken hold in Egyptian hearts.

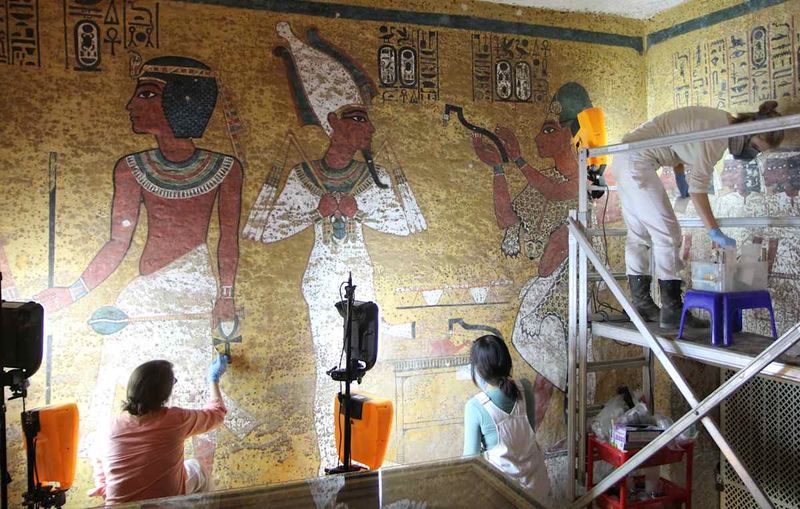

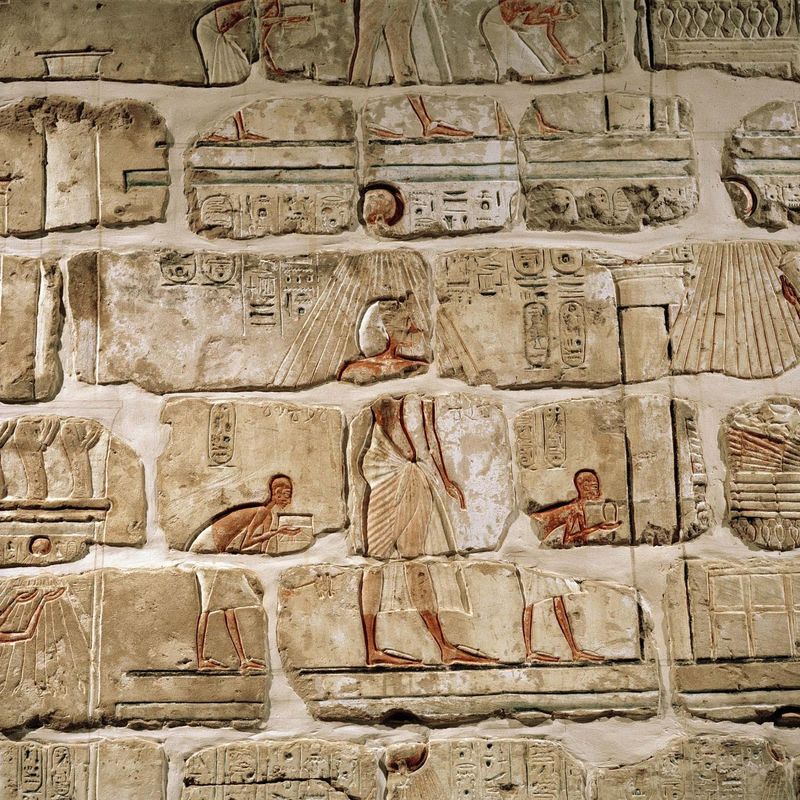

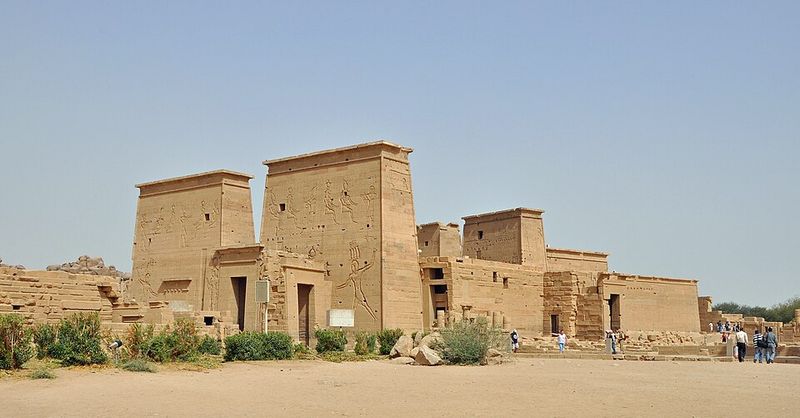

2. Help Rebuild Damaged Temples

Crumbling sanctuaries needed urgent attention after years of neglect. Tutankhamun’s government organized massive restoration projects, requiring citizens to contribute labor or resources according to their abilities. Artisans carved fresh images of traditional gods on temple walls while farmers delivered portions of their harvests to support priests. Stone workers and builders traveled far from home, often spending months away from their families to repair sacred sites. These restoration efforts weren’t just religious duties—they provided employment and economic stability. Communities took pride in their renovated temples, which once again became centers of both spiritual and social life throughout the Nile Valley.

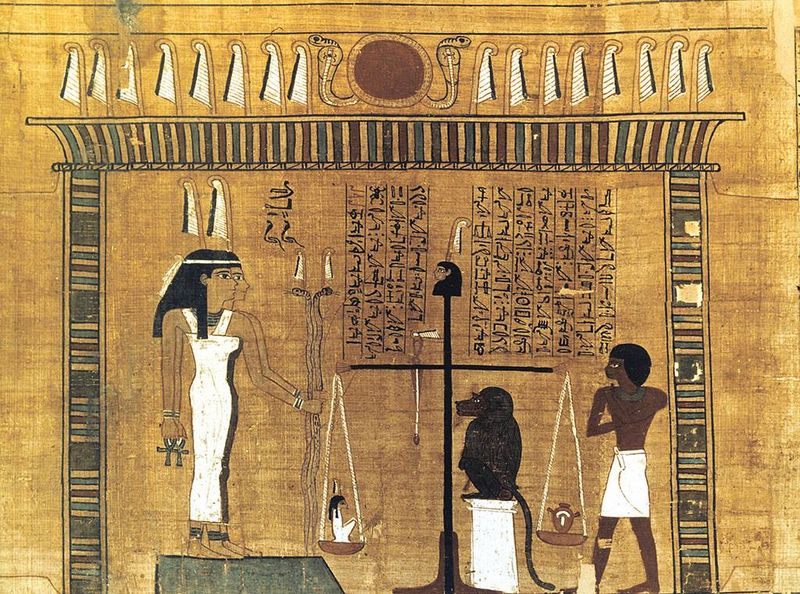

3. Live By The Principles Of Maat

Truth, justice, and cosmic balance weren’t just lofty ideals—they were daily requirements. Every Egyptian was expected to embody Maat in their actions, from telling the truth to treating neighbors fairly. This invisible code governed everything from business transactions to family disputes. Farmers measured field boundaries honestly. Merchants weighed goods with accurate scales. Even in private moments, people believed the goddess Maat watched their hearts. The concept extended beyond morality into maintaining natural harmony. Respecting the Nile’s cycles, honoring ancestors, and keeping one’s place in society all fell under Maat’s umbrella. Those who violated these principles risked divine punishment and community rejection.

4. Obey The Boy-King Without Question

Despite his youth, Tutankhamun’s word was absolute law. When royal decrees arrived in villages, citizens bowed their heads in immediate acceptance, regardless of personal opinions. The pharaoh wasn’t just a ruler but a living god on earth. Royal officials traveled the kingdom enforcing the king’s will. They collected taxes, conscripted workers for royal projects, and ensured public compliance with official policies. Challenging these representatives meant challenging the divine order itself. Even nobles and priests had to demonstrate perfect loyalty. Court ceremonies required elaborate displays of submission, with everyone from high officials to servants prostrating themselves before the royal throne. This absolute authority system maintained stability during the young king’s reign.

5. Accept Religious Diversity

Surprisingly modern in approach, Tutankhamun’s government didn’t force immediate religious conformity. Families who had embraced Aten worship under Akhenaten weren’t persecuted, though they gradually rejoined mainstream practices. This pragmatic tolerance prevented further social upheaval. Communities that had been divided by religious differences slowly healed as people worshipped according to their conscience while the official religion returned to tradition. Foreign merchants and diplomats maintained their own religious customs while in Egypt. Nubians, Canaanites, and others living within Egyptian borders continued honoring their ancestral gods alongside respecting Egyptian deities. This practical approach to religious differences helped stabilize the kingdom during Tutankhamun’s short reign.

6. Change Your Aten-Inspired Name

Names carried powerful magic in ancient Egypt. When Tutankhamun changed his own name from Tutankhaten (“living image of Aten”) to Tutankhamun (“living image of Amun”), subjects followed his example. Families visited temples to officially record name changes, replacing “Aten” elements with traditional deity references. Parents renamed young children while adults adopted new identities reflecting allegiance to restored gods. These changes weren’t merely administrative—Egyptians believed names connected directly to one’s soul and destiny. Court officials led this transformation, sometimes changing not just names but entire personal histories to distance themselves from Akhenaten’s era. Tomb inscriptions and family records were modified, effectively rewriting recent history to align with the restored religious order.

7. Support The Temple Economy

Temples weren’t just worship centers—they were economic powerhouses. Every citizen contributed to this system through taxes, offerings, or labor. Farmers delivered grain quotas while craftspeople donated finished goods or worked directly on temple lands. These religious institutions employed thousands as priests, artisans, farmers, and administrators. They operated bakeries, breweries, and workshops that produced everything from bread to furniture. Common people could find employment in these temple economies, providing stable income for families. Beyond material support, citizens participated in temple marketplaces, rented agricultural land from religious estates, and sought temple loans during hard times. This intertwined economic-religious system formed the backbone of Egyptian society, with everyone expected to maintain their role within it.

8. Join Religious Festival Celebrations

Colorful processions and joyous feasts marked Egypt’s religious calendar. When temple drums announced festivals like Opet or the Beautiful Feast of the Valley, everyone from peasants to nobles participated in these community celebrations. Work stopped as golden god-statues emerged from temple sanctuaries, carried through streets on elaborate barques. Families lined procession routes, throwing flowers and offering prayers while musicians played and dancers performed. These weren’t optional social events—they reinforced cosmic order. Behind the festivities lay serious purpose: ensuring continued divine favor for Egypt. Citizens brought offerings according to their means, shared ceremonial meals, and performed ritual acts at specific sacred locations. Absence without good reason showed disrespect to both community and gods.

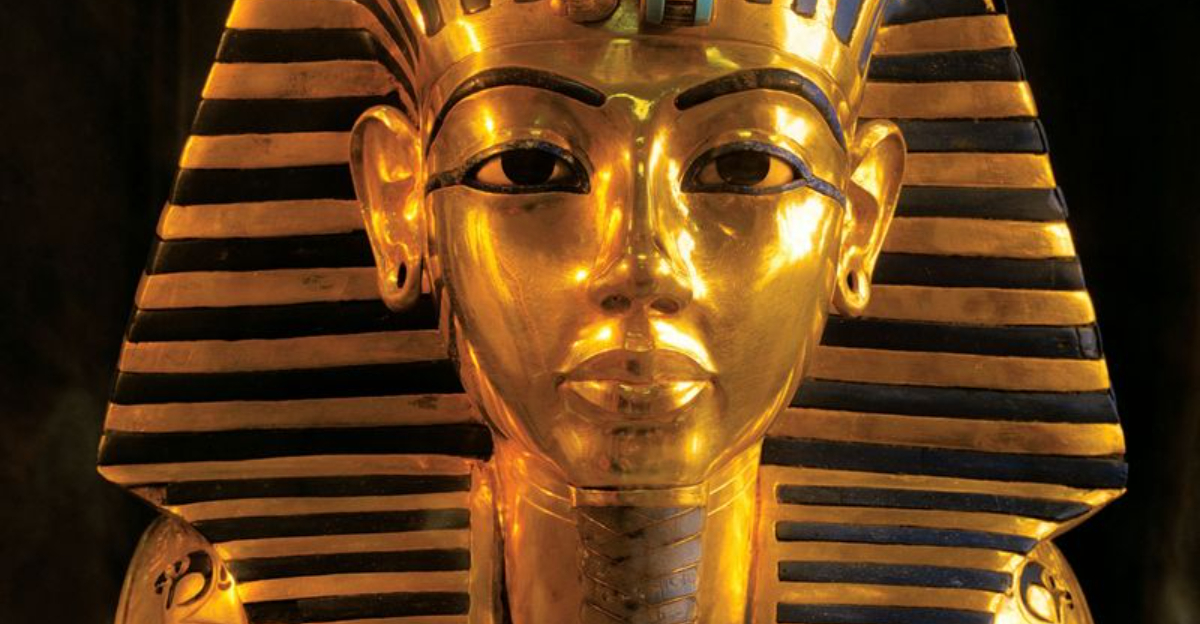

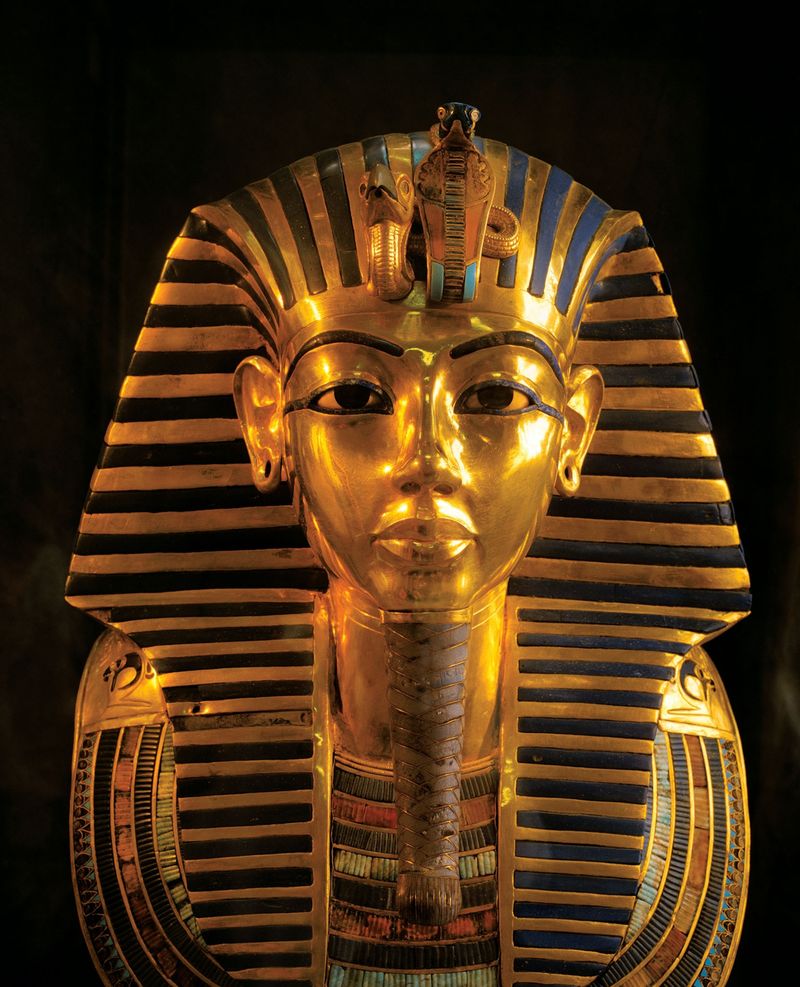

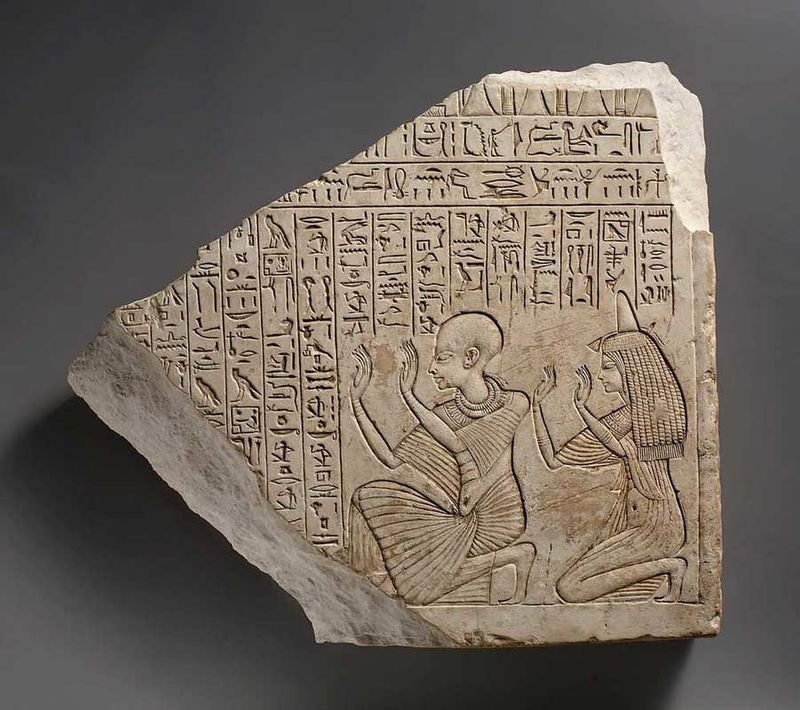

9. Prepare Properly For The Afterlife

Death preparations began during life itself. From humble farmers to wealthy officials, everyone saved resources for proper funeral arrangements based on their social status. Families accumulated burial goods throughout their lifetimes, ensuring loved ones would reach the afterlife properly equipped. Mummification—once reserved for royalty—had extended to anyone who could afford it. Modified versions of sacred texts like portions of the Book of the Dead became essential funerary items. Even modest tombs required specific magical spells and protective amulets. Beyond physical preparations, moral conduct mattered enormously. Egyptians believed their hearts would be weighed against the feather of truth after death. This belief encouraged ethical living and proper observance of religious duties as the ultimate preparation for eternal life.

10. Resolve Disputes Through Local Authorities

Justice began at the village level under Tutankhamun’s rule. When conflicts arose over property boundaries, inheritance, or personal injuries, citizens first brought their cases to local councils of elders rather than royal courts. These kenbet councils met in public spaces, often near the village gate. Witnesses testified openly while respected community members evaluated evidence and suggested resolutions based on precedent and common sense. Most everyday disputes never reached higher authorities. For serious matters like theft or violence, regional officials appointed by the pharaoh could intervene. The vizier—Egypt’s highest official below the king—handled only the most significant cases. This multilayered system maintained order while keeping royal courts free to address matters of state importance.