The Mayan civilization was one of the most advanced ancient cultures in the Americas, thriving for over 3,000 years across Mexico and Central America. They built incredible cities, created a complex writing system, and developed remarkable knowledge of astronomy and mathematics. Yet despite centuries of research, archaeologists and historians still puzzle over many aspects of this fascinating civilization that continue to defy simple explanation.

1. What Caused the Classic Maya Collapse (Around 900 AD)?

This mysterious disappearance happened across the Maya lowlands around 900 AD, when populations declined by 90% in some regions.

Scientists have proposed numerous theories: severe drought, warfare between city-states, overpopulation straining resources, peasant revolts against elites, or devastating epidemics. Tree ring and lake sediment data support the drought hypothesis.

What’s particularly puzzling is that different Maya regions collapsed at slightly different times and for potentially different reasons. The collapse wasn’t uniform, making it one of archaeology’s greatest mysteries—how could such a sophisticated civilization virtually disappear?

2. How Did They Develop Such Advanced Astronomy?

The night sky held profound meaning for Maya astronomers, who tracked celestial movements with astonishing accuracy. Without telescopes or modern instruments, they calculated the lunar cycle to within 34 seconds of modern measurements.

Their Venus tables predicted the planet’s appearances with just a two-hour error over 584 days. Even more remarkably, they developed the Long Count calendar capable of tracking time over vast periods—their calculations extend millions of years into past and future.

Archaeoastronomers remain puzzled by how such precision was possible with naked-eye observations alone. The Maya built observatories like El Caracol at Chichen Itza, but the knowledge transfer system that allowed them to compile centuries of astronomical data remains largely unknown.

3. What Was the Purpose of Their Ball Courts?

The thunderous echo of a rubber ball bouncing off stone walls once filled Mayan ball courts—massive I-shaped arenas found in nearly every city. At Chichen Itza’s Great Ball Court, a whisper at one end can be heard 500 feet away, and the acoustic properties create sounds resembling bird calls or rainfall.

Players used hips and shoulders—never hands—to knock a solid rubber ball through stone hoops mounted high on walls. Stone carvings suggest the game had cosmic significance, representing the movement of celestial bodies.

The game’s outcome could be life-or-death serious. Some reliefs show the losing captain being sacrificed, while others depict victors suffering this fate—considered an honor. Were these elaborate courts primarily for sport, religious ritual, political theater, or all three?

4. How Did They Build Such Precise Pyramids Without Metal Tools or Wheels?

Standing before a Mayan pyramid feels like witnessing the impossible. These massive structures align perfectly with celestial events—El Castillo at Chichén Itzá creates a serpent shadow during equinoxes that slithers down the staircase with mathematical precision.

The Maya quarried, shaped, and transported enormous limestone blocks weighing tons each. Yet they accomplished this architectural marvel without metal tools, wheels, or draft animals like oxen or horses.

Archaeologists believe they used stone tools, wooden levers, and countless human laborers, but the precision achieved remains baffling. How did they cut such perfect angles and align structures to astronomical events with such accuracy using primitive tools?

5. Why Did They Practice Extreme Body Modification?

Maya beauty standards would shock modern sensibilities. Noble parents carefully bound infants’ heads between boards to create an elongated, sloped forehead—a permanent mark of elite status. The pain didn’t end there.

Maya nobility drilled holes in their teeth to insert jade inlays and filed them into pointed shapes. Cross-eyed vision was considered beautiful, so parents dangled objects before their children’s eyes to permanently alter their vision.

Both men and women endured painful scarification, tattooing, and piercing rituals. These modifications weren’t simply fashion statements but deeply intertwined with religious beliefs and social hierarchy. What’s perplexing is the extremity of these practices despite their permanent, sometimes debilitating effects—suggesting powerful cultural motivations we still don’t fully comprehend.

6. How Did Their Writing System Remain Undeciphered for So Long?

Mayan hieroglyphs taunted scholars for centuries, their meanings locked away despite being in plain sight. Unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were deciphered after the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, Mayan writing remained largely mysterious until the 1970s-80s.

The Spanish conquistadors destroyed thousands of Mayan codices—bark-paper books—considering them works of the devil. Only four survived, leaving archaeologists with limited source material.

Russian linguist Yuri Knorozov made the breakthrough by realizing the glyphs combined both phonetic and logographic elements. Even today, about 15% of known glyphs remain undeciphered. The writing system’s complexity—with over 800 signs representing syllables, whole words, and concepts—makes it one of history’s most sophisticated scripts, raising questions about how such complexity evolved in isolation.

7. What Happened to Their Mysterious “Blue Pigment”?

The vibrant turquoise known as “Maya Blue” has survived centuries of harsh tropical conditions while modern paints would have long since faded. This remarkable pigment adorns murals, pottery, and even human sacrifices at sacred cenotes like Chichen Itza.

Scientists only recently discovered its secret—a unique combination of indigo plant dye and palygorskite clay, heated to create an extraordinarily stable compound. The knowledge of how to create this pigment disappeared after the Spanish conquest.

What’s fascinating is how the Maya developed this complex chemical process without modern scientific understanding. The pigment’s remarkable durability suggests they discovered principles of molecular bonding through experimentation. Was this sophisticated chemistry the result of trial and error, or did they possess a systematic understanding of materials that was lost to history?

8. Were the Maya in Contact with Other Civilizations?

Strange figures appear in Mayan art that don’t quite fit the expected pattern. Carvings at Copán and other sites show bearded individuals with non-Maya features—unusual since indigenous Americans typically have sparse facial hair.

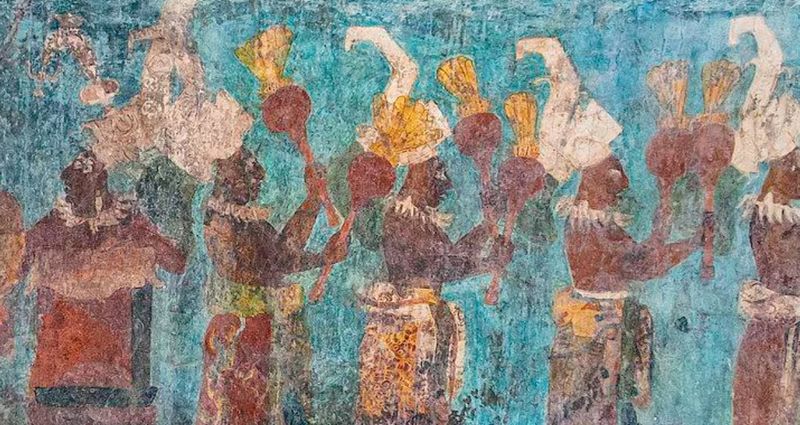

The famous “Tecún Umán” relief depicts what some interpret as a figure with African features. At Chichen Itza, murals show possible contact with central Mexican cultures, but some researchers see hints of more distant connections.

Archaeological evidence confirms trade with distant Mesoamerican peoples, but the debate continues about potential pre-Columbian contact with cultures across oceans. Similarities between Mayan and Asian religious symbols have fueled speculation. Did isolated artistic coincidences create these resemblances, or might the Maya have encountered visitors from across the seas long before Columbus?

9. What Was the True Purpose of Human Sacrifice?

Blood-red handprints still stain the walls of ancient Maya temples, silent witnesses to rituals we struggle to comprehend. While less extensive than Aztec practices, Maya human sacrifice was nonetheless central to their religious life—from royal bloodletting to heart extraction and decapitation.

The sacred cenote at Chichen Itza has yielded hundreds of human remains, many of children. Hieroglyphs describe these victims as “divine nourishment” for the gods.

Modern scholars debate whether these practices served purely religious purposes or had additional functions. Did they reinforce social control through terror? Were they responses to ecological stress? The psychological impact of witnessing such rituals must have been profound, yet Maya society maintained these practices for centuries—suggesting complex motivations beyond simple bloodlust that remain difficult for modern minds to fully grasp.

10. Where Did Their Knowledge of Zero Come From?

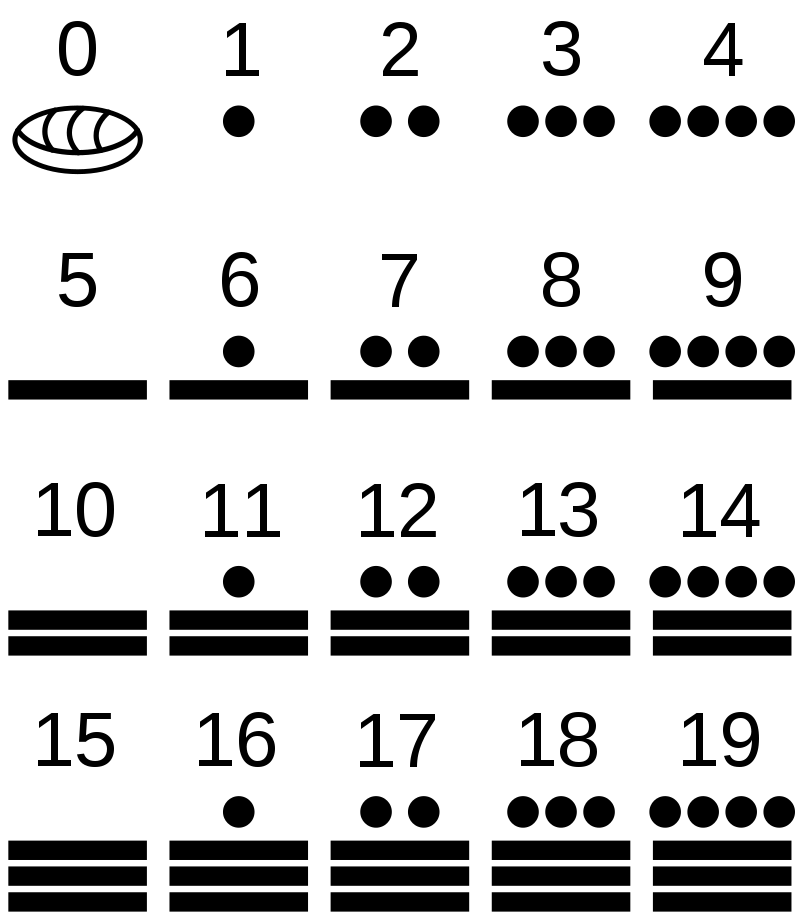

A shell-shaped glyph representing nothingness revolutionized mathematics in the Americas. The Maya invented zero as a placeholder value around 350 AD—centuries before European mathematicians adopted the concept from Arabic numerals.

This mathematical breakthrough allowed them to calculate sums in the millions and track vast time periods in their calendars. The Maya developed this concept independently from Old World civilizations, using a vigesimal (base-20) system rather than our familiar decimal system.

The concept of zero represents a profound philosophical leap—the idea that nothingness deserves its own symbol. How did multiple civilizations separately arrive at this abstract concept? The Maya understanding of zero as both emptiness and completion suggests a sophisticated mathematical philosophy that emerged without known outside influence, raising questions about how mathematical thinking evolves across cultures.