Monks have always lived by rules that seem strange to the outside world. Throughout history, Christian monasteries developed unique practices to help monks focus on prayer and spiritual growth.

From extreme isolation to unusual daily schedules, these rules shaped monastic life in ways that might surprise you.

1. Walled-Up For Life: The Extreme Isolation of Anchorites

Imagine choosing to be bricked into a tiny room attached to a church—for the rest of your life! Anchorites and anchoresses volunteered for this extreme form of isolation, living in small cells with only a window to receive food and another opening to hear Mass.

These dedicated souls spent their days in constant prayer, often becoming spiritual advisors to people who would visit their window seeking guidance. Julian of Norwich, a famous 14th-century anchoress, wrote her revelations during her enclosure.

Once the ceremony of enclosure was complete, funeral rites were performed—the anchorite was considered dead to the world while still living!

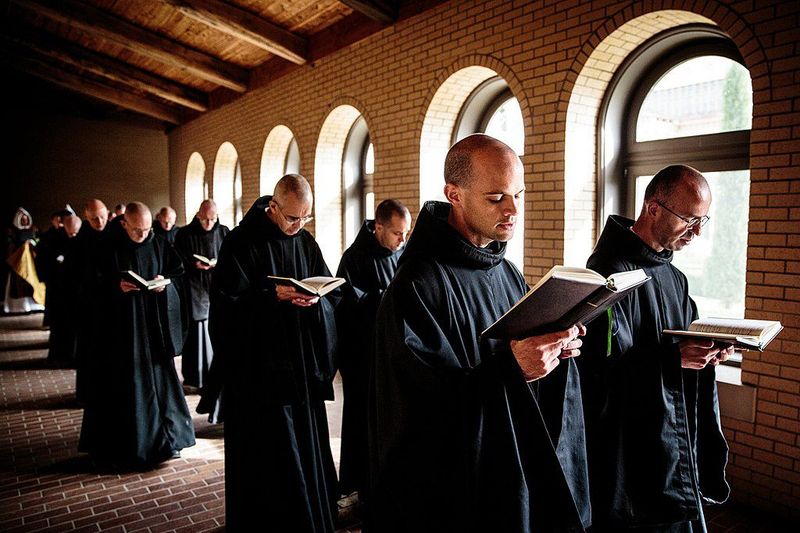

2. Never-Ending Prayer Shifts Around The Clock

Sleep? Who needs it when there are prayers to be said! The practice of laus perennis (perpetual praise) meant that monasteries arranged monks in rotating teams to ensure prayers continued 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

First established in the monastery of Agaunum (now Saint-Maurice) in Switzerland around 522 CE, this practice spread throughout Europe. Monks would take shifts, with each group singing the Divine Office before being relieved by the next team.

Just imagine the dedication—no matter the hour, weather, or season, the monastery’s prayers never ceased, creating what they believed to be an unbroken chain of worship to God.

3. One Meal A Day—And No Meat Allowed

Forget breakfast, lunch, and dinner—many medieval monks ate just once daily! Following Saint Columbanus’s strict rule, Irish monks limited themselves to a simple evening meal of beans, vegetables, and bread, often after sunset.

During special fasting periods, even this meager meal might be reduced further. Water was the primary drink, though some monasteries permitted small amounts of beer or wine.

The purpose wasn’t just self-denial. Monks believed hunger sharpened spiritual awareness and helped overcome bodily desires. Plus, these dietary restrictions served as a constant reminder of their vow of poverty and separation from worldly pleasures that ordinary people enjoyed.

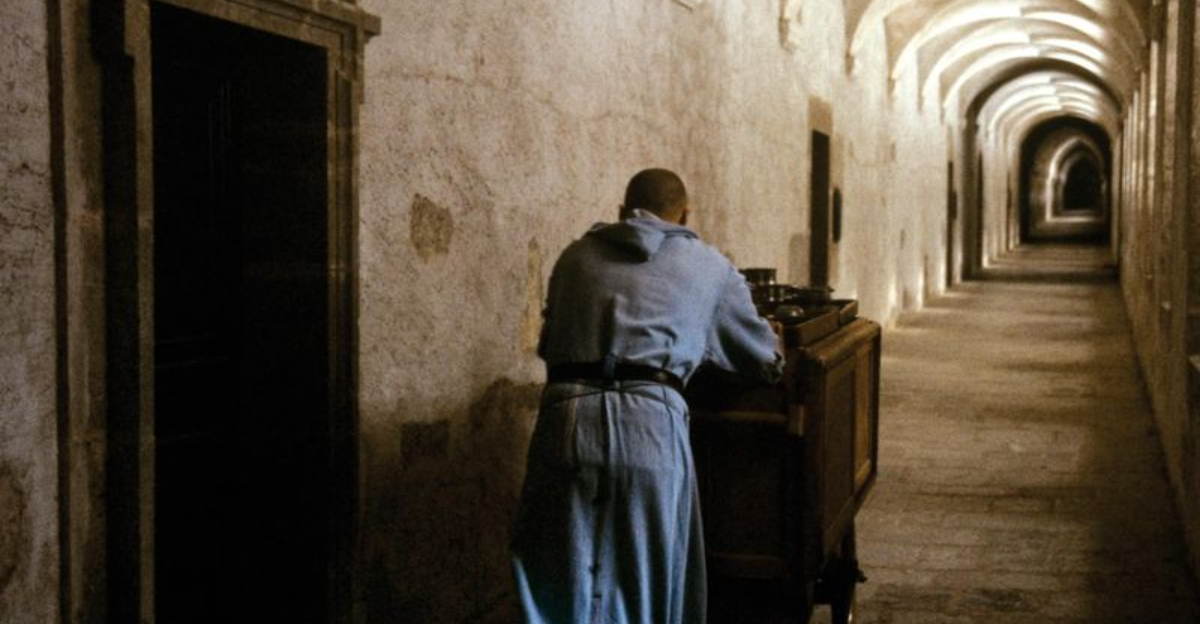

4. The Great Silence: Years Without Speaking

The walls weren’t the only silent things in medieval monasteries! Many orders required monks to maintain complete silence for most of the day and night. The Carthusian Order, founded in 1084, took this practice to extraordinary levels—monks would go years speaking only during weekly chapter meetings and occasional recreation periods.

Monks developed elaborate sign languages to communicate essential information without breaking their vow of silence. Even today, Carthusians speak so rarely that many develop throat problems when they do need to talk.

Saint Benedict considered excessive talking a gateway to sin and idle chatter. His famous rule states: “Speaking and teaching belong to the master; the disciple’s part is to be silent and to listen.”

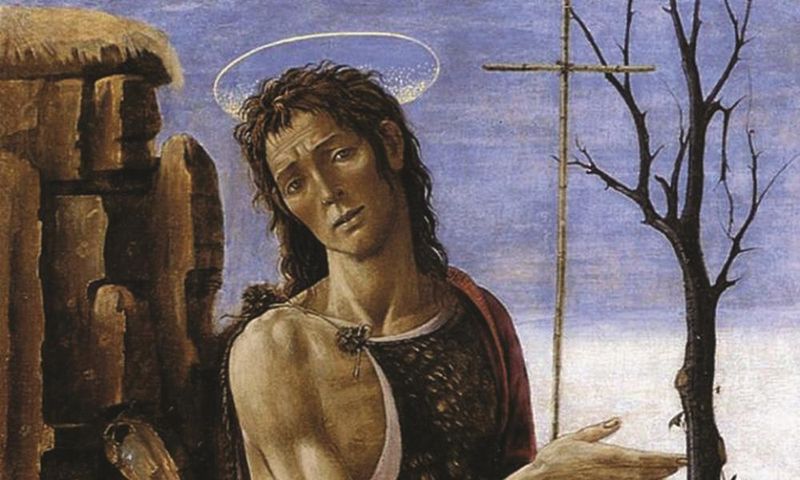

5. Women As Dangerous Temptations To Be Avoided

Some monastic rules treated women as walking spiritual dangers! Many male monasteries enforced strict separation, forbidding monks from speaking to or even looking directly at women. The Desert Fathers of early Christianity were particularly extreme—Saint Jerome advised monks to “flee from women as you would from a viper.”

Irish monastic rules forbade monks from traveling alone on roads where women might be encountered. Some monasteries even had special visitor areas where monks could meet female relatives, but only with witnesses present and through iron grilles.

This avoidance wasn’t just about temptation—monks believed women’s very presence could disrupt their spiritual focus and community harmony.

6. Sunset Marks The Start Of A New Day

While most of us start our day at midnight or sunrise, monks at Mount Athos follow Byzantine time—their day begins at sunset! This ancient timekeeping system aligns with the Biblical creation story where “there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.”

Their clock faces look familiar but read differently. When the sun sets, the clock strikes midnight, and a new day begins. This means their daily schedule shifts throughout the year as sunset times change.

Adding to the uniqueness, Mount Athos still follows the Julian calendar, which runs 13 days behind the modern Gregorian calendar. A visitor might arrive thinking it’s July 15th only to discover the monks are celebrating July 2nd!

7. Uncomfortable By Design: Wearing Hairshirts As Penance

Imagine wearing an itchy, scratchy shirt made from animal hair directly against your skin—on purpose! Many monks wore hairshirts (cilice) as a form of voluntary suffering and penance. These garments were deliberately uncomfortable, made from coarse goat or horse hair woven into a rough fabric.

The Valliscaulian Order, founded in Burgundy in the late 12th century, required all their monks to wear hairshirts beneath their regular robes. The constant irritation served as a reminder of Christ’s suffering and helped monks resist physical comforts.

Some particularly devoted monks would wear their hairshirts for years without removing them, leading to skin infections and sores they viewed as badges of spiritual devotion!

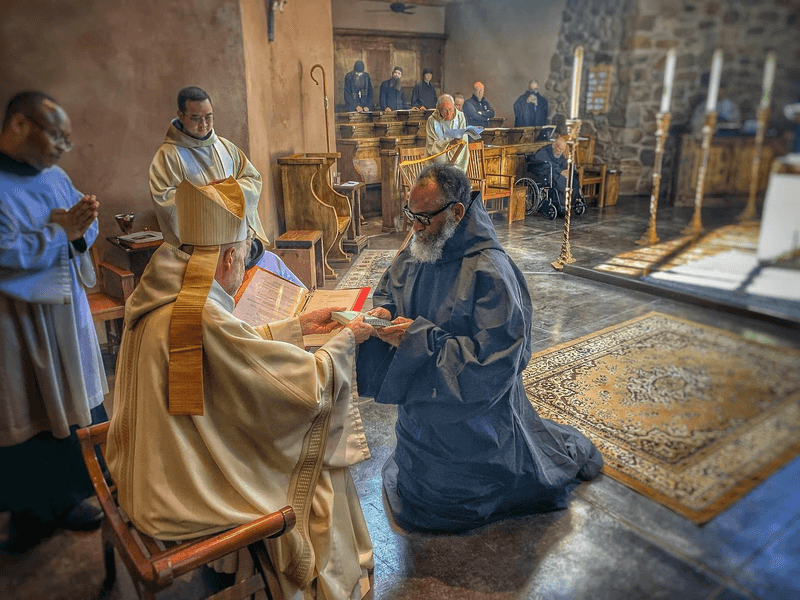

8. Work As Worship: Labor As A Sacred Duty

“Idle hands are the devil’s workshop” took on special meaning in monasteries! The famous Benedictine motto “Ora et Labora” (Pray and Work) established manual labor as a form of worship equal to formal prayer. Monks weren’t just praying—they were farming, brewing beer, copying manuscripts, and building.

Cistercian monks became expert farmers, transforming European agriculture with innovative techniques. Their day was carefully divided between prayer services and work periods, with no time for leisure.

Even high-born nobles who entered monasteries had to perform physical labor alongside commoners—a revolutionary concept in medieval society. The purpose was threefold: sustaining the community, avoiding idleness, and practicing humility through manual tasks.

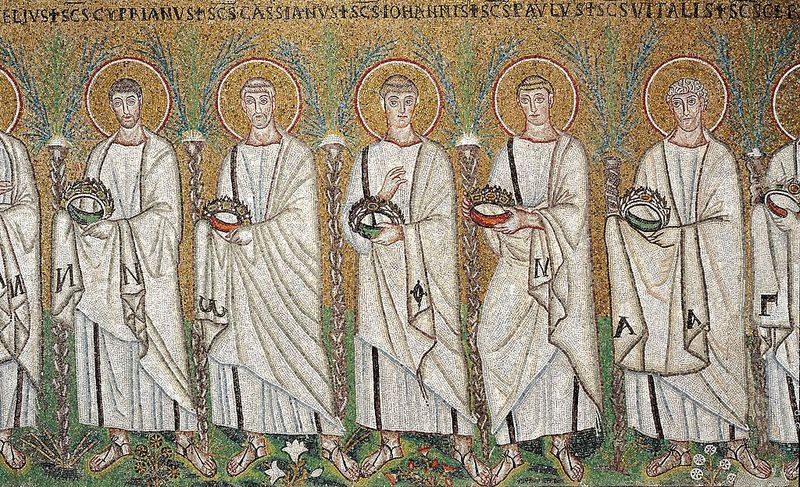

9. Sacred Friendship Ceremonies Between Monks

While strictly celibate, some medieval monks participated in formal friendship ceremonies called “adelphopoiesis” or “brother-making.” These rituals created spiritual bonds between monks that went beyond ordinary friendship but weren’t romantic relationships.

The ceremony involved prayers, holding hands, receiving communion together, and sometimes exchanging kisses of peace. Afterward, the monks were considered “brothers by choice” rather than by blood.

Historical records from Byzantine and Eastern Orthodox traditions show these relationships were blessed by the church and considered holy bonds. Scholars continue to debate their exact nature, but they represent a unique form of sanctioned emotional intimacy within the otherwise austere monastic life.

10. No Females Allowed—Not Even Female Animals

Mount Athos takes the “no girls allowed” rule to extraordinary lengths! This peninsula in Greece has banned all females—not just women but female animals too—since the 11th century. The only exceptions are cats (for pest control) and songbirds that naturally inhabit the area.

Legend claims the Virgin Mary once shipwrecked near Mount Athos and blessed it as her garden, decreeing it should be free from female presence. Even female livestock are prohibited—monks import meat rather than raise hens or cows.

This rule remains strictly enforced today. Female visitors face up to twelve months in prison if caught trying to enter this UNESCO World Heritage site that houses twenty Orthodox monasteries and approximately 2,000 monks.