History books often celebrate leaders who changed the world through bold actions and decisive moves. But what about those who failed to act when action was most needed?

These rulers and presidents held immense power yet hesitated, ignored problems, or simply refused to adapt to changing times.

Their stories serve as important reminders that leadership requires more than just holding a title – it demands courage to face challenges head-on.

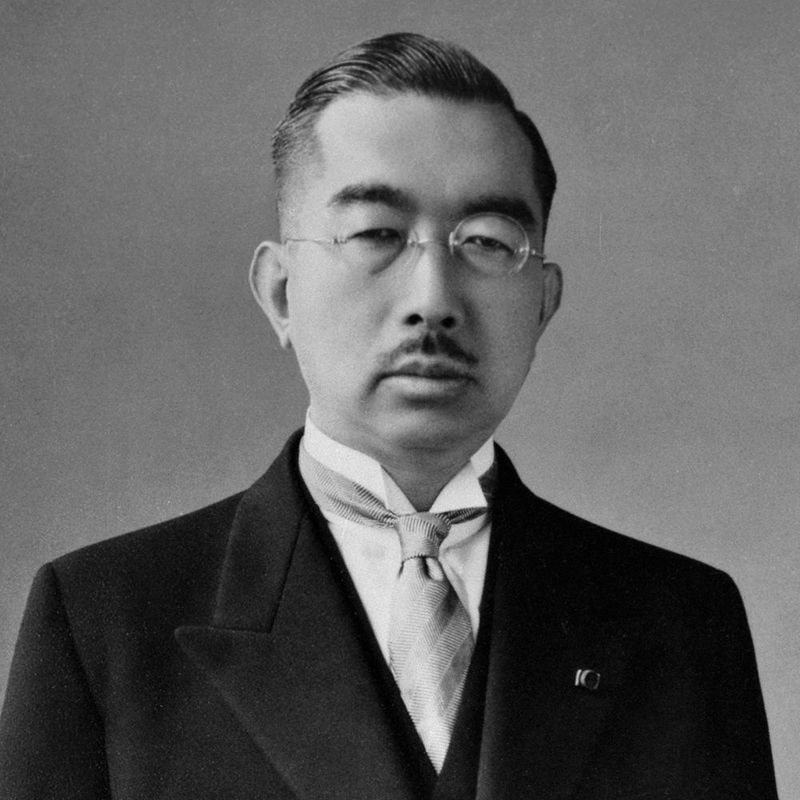

1. Emperor Hirohito: The Passive Wartime Ruler

Behind the imperial curtains, Japan’s 124th emperor maintained a puzzling silence during World War II. Though technically commander-in-chief, Hirohito rarely challenged his military leaders as they embarked on devastating campaigns across Asia.

His reluctance to intervene earlier in the war extended the conflict and multiplied suffering. Only after atomic bombs devastated Hiroshima and Nagasaki did he finally assert authority with his historic surrender broadcast.

Hirohito survived the post-war period by transforming into a symbolic figurehead, never fully addressing his wartime responsibility. This strategic inaction preserved his throne but left lasting questions about his moral leadership.

2. King Louis XVI: The Monarch Who Couldn’t Decide

Inheriting the French throne at age 20, Louis XVI faced a nation drowning in debt and seething with discontent. Rather than tackle these problems directly, he bounced between advisors and delayed crucial reforms.

His famous diary entry on July 14, 1789 – the day revolutionaries stormed the Bastille – simply read “Nothing,” revealing his disconnection from reality. When he did act, his half-measures only inflamed the situation.

Louis repeatedly postponed financial reforms while maintaining lavish court expenses. His indecisiveness created a leadership vacuum that revolutionary forces eagerly filled, ultimately costing him both his crown and his head.

3. Tsar Nicholas II: The Reluctant Reformer

Russia’s last tsar clung to autocratic traditions while the world modernized around him. Nicknamed “Nicholas the Bloody” after ordering troops to fire on peaceful protesters in 1905, he repeatedly failed to address the growing social unrest.

His response to crises followed a predictable pattern: initial resistance, belated half-measures, then retreat to his family circle. During World War I, his decision to personally command the army proved disastrous, leaving the government rudderless.

While revolutionaries organized and soldiers deserted, Nicholas remained isolated at his headquarters. His failure to implement meaningful reforms when he had the chance accelerated Russia’s slide into revolution.

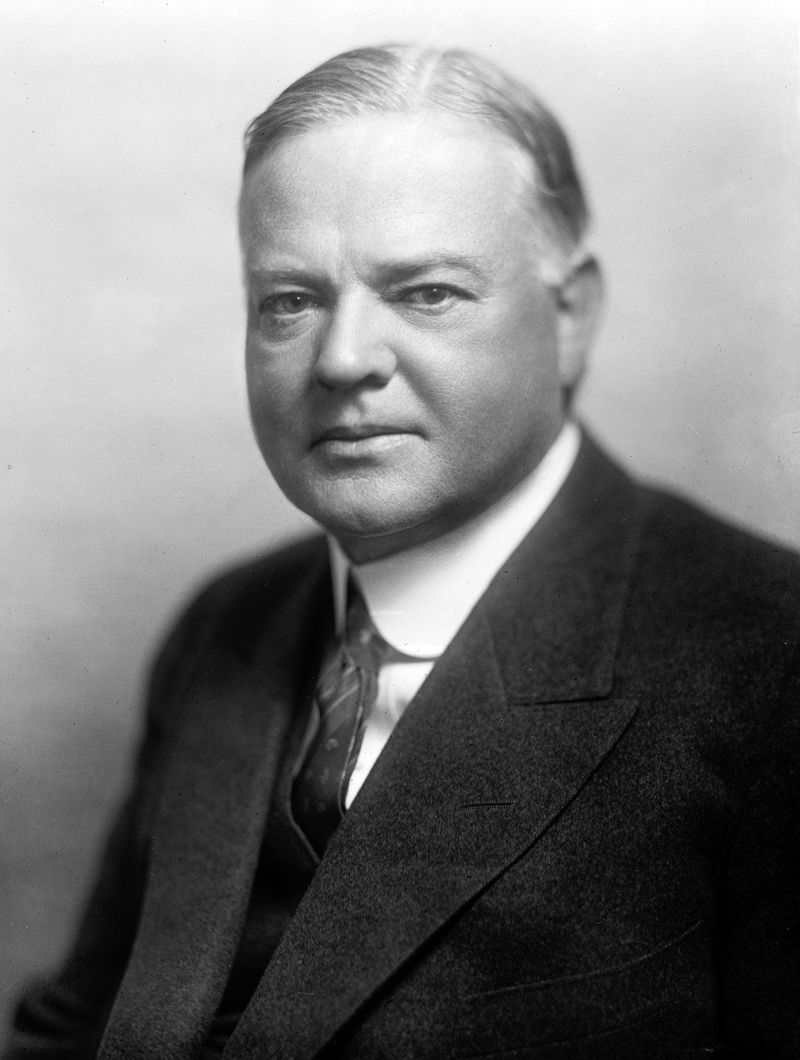

4. President Herbert Hoover: The Depression’s Bystander

Before becoming president, Herbert Hoover gained fame as a brilliant problem-solver and humanitarian. Yet when the Great Depression struck in 1929, this once-dynamic leader froze like a deer in headlights.

Clinging to beliefs that the economy would naturally correct itself, Hoover resisted direct federal intervention to help suffering Americans. His famous statement that “prosperity is just around the corner” rang hollow as unemployment soared to 25%.

While millions lost homes and livelihoods, Hoover’s limited responses – like the Reconstruction Finance Corporation – came too late and did too little. His paralysis during America’s greatest economic crisis defined his presidency and transformed his name into a symbol of governmental neglect.

5. Emperor Xianfeng: China’s Opium Crisis Non-Manager

Ascending to China’s throne at just 19, Emperor Xianfeng inherited a nation already reeling from the First Opium War. Instead of confronting these challenges, he retreated into palace pleasures and delegated power to corrupt officials.

When Western powers demanded more concessions, Xianfeng vacillated between appeasement and empty threats. His court’s indecision culminated in the disastrous Second Opium War, which saw foreign troops loot and burn the magnificent Summer Palace.

Rather than rally his nation, Xianfeng fled Beijing for his hunting lodge at Jehol. There, isolated from reality and reportedly consumed by opium addiction himself, he died at 30, leaving China weaker than he found it.

6. King John: England’s Reluctant Ruler

Forever living in the shadow of his charismatic brother Richard the Lionheart, King John earned his notorious reputation through hesitation and poor judgment. When French King Philip II seized Normandy, John earned the nickname “Softsword” for failing to mount an effective defense.

His passive approach to kingship extended to domestic affairs as well. Rather than building alliances with powerful barons, John alienated them through arbitrary taxation and judicial abuses.

The famous Magna Carta of 1215 wasn’t a document John willingly signed – it was forced upon him by barons fed up with his misrule. Even then, John quickly reneged on his promises, triggering civil war and inviting French invasion before his timely death.

7. President Paul von Hindenburg: Democracy’s Reluctant Guardian

As Germany’s aging president during the Weimar Republic’s final years, former Field Marshal Hindenburg was democracy’s unlikely last defender. At 84, he watched passively as economic crisis and political extremism tore at Germany’s fragile democratic fabric.

Though personally opposed to Hitler, Hindenburg failed to use his emergency powers to prevent Nazi ascendance. His fateful decision in January 1933 to appoint Hitler as Chancellor – believing he could be controlled – opened the door to dictatorship.

Hindenburg spent his final months rubber-stamping Hitler’s increasingly authoritarian decrees. His death in 1934 removed the last institutional check on Nazi power, completing a transition to tyranny that his earlier inaction had enabled.

8. King Farouk I: Egypt’s Playboy Monarch

While Egypt struggled under British influence and poverty gripped his nation, King Farouk dedicated himself to an extraordinary lifestyle of excess. His collection of luxury cars, jewelry, and even pornography became legendary while his subjects suffered.

During World War II, Farouk’s sympathies toward Axis powers and corruption scandals eroded his legitimacy. Rather than addressing Egypt’s pressing social problems or leading anti-colonial efforts, he focused on personal pleasures.

As nationalist sentiment grew, Farouk responded with half-hearted reforms that satisfied nobody. His famous last meal before being overthrown in 1952 – reportedly a 30-course dinner – perfectly symbolized his disconnection from Egypt’s reality and his failure to meet the moment his country needed leadership.

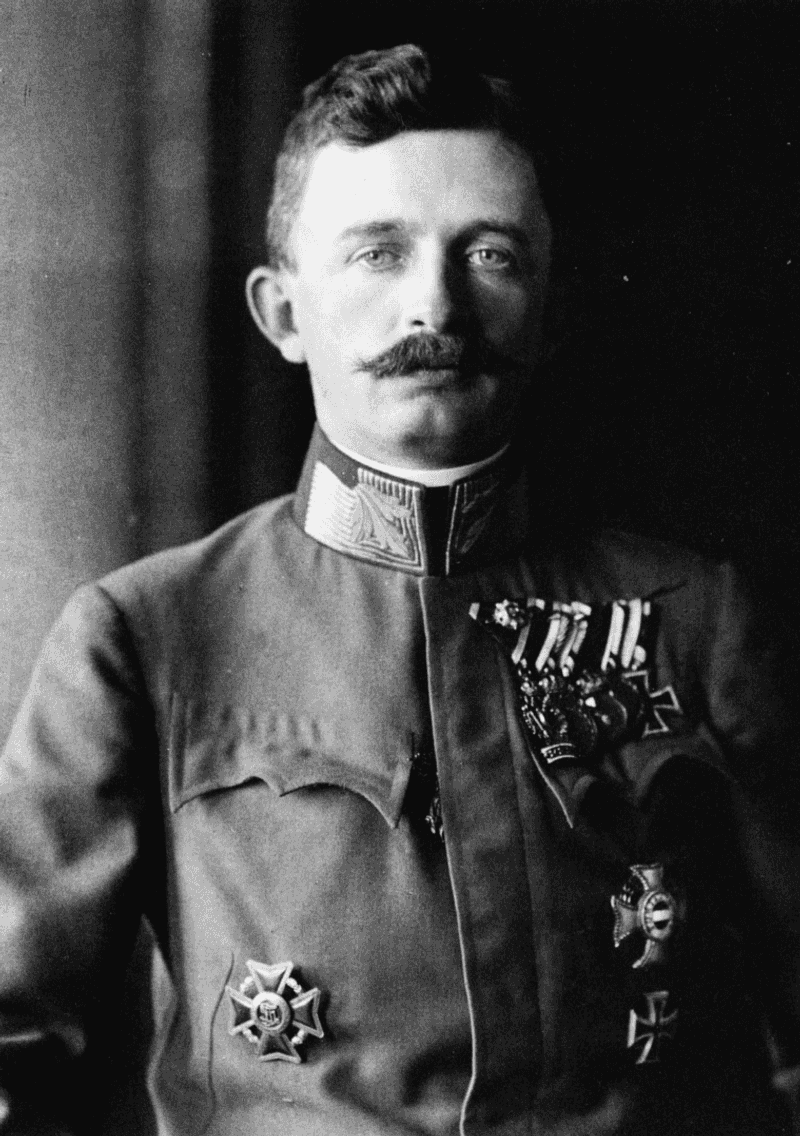

9. Emperor Charles I: Austria-Hungary’s Final Chance

Taking the throne mid-World War I, young Emperor Charles inherited a crumbling multi-ethnic empire desperately needing reform. Though personally inclined toward peace, Charles lacked the decisiveness to extract Austria-Hungary from its disastrous German alliance.

His secret peace negotiations with Allied powers in 1917 revealed good intentions but poor execution. When discovered, these half-measures only damaged his credibility with both sides.

As nationalist movements gained momentum within his empire, Charles hesitated between repression and concession. His belated proposal for a federal restructuring came too late to save the Habsburg monarchy. By war’s end in 1918, Charles hadn’t abdicated so much as watched his empire dissolve around him.

10. King Umberto II: Italy’s Month-Long Monarch

Nicknamed the “May King” for his incredibly brief 34-day reign, Umberto II represents perhaps the most extreme case of royal inaction. As Italy emerged from fascism and World War II, Umberto failed to distance himself from his father’s collaboration with Mussolini.

When Italians voted in a 1946 referendum on the monarchy’s fate, Umberto did little to champion constitutional monarchy as a viable path forward. His passive acceptance of his father’s abdication came too late to rebuild public trust.

After losing the referendum, Umberto departed for Portugal without resistance. While this peaceful transition spared Italy further conflict, it highlighted how thoroughly the monarchy had failed to adapt to modern democratic sentiments.

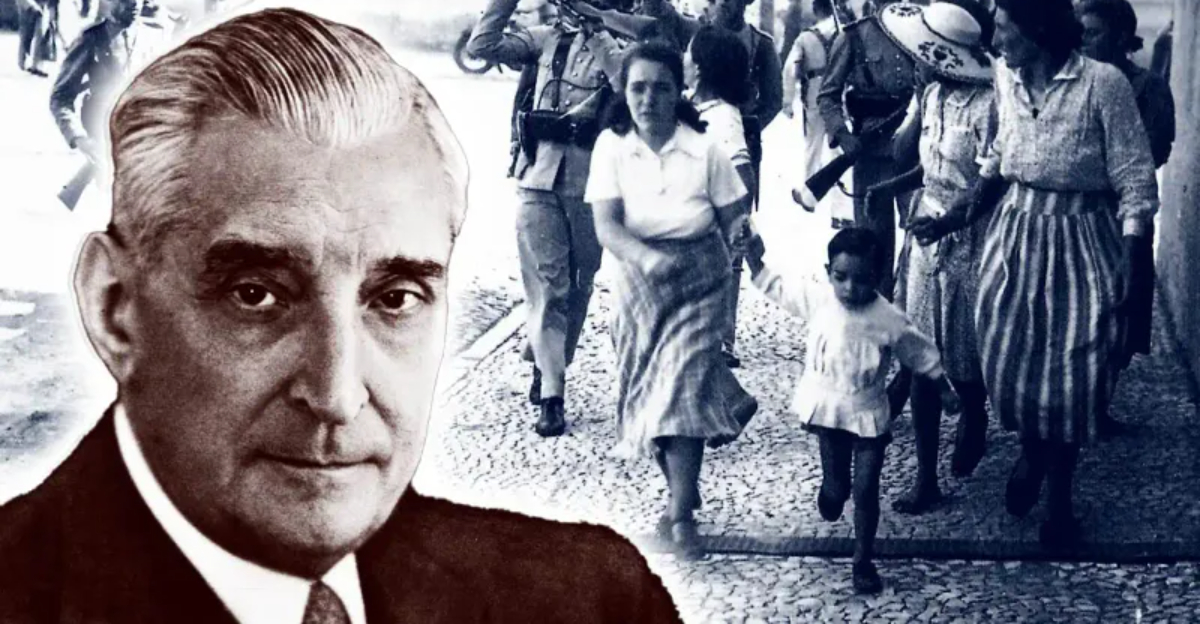

11. President António Salazar: Portugal’s Fading Dictator

After decades as Portugal’s authoritarian ruler, Salazar’s final years revealed the dangers of a leader who refuses to adapt. As colonial wars drained Portugal’s resources in the 1960s, the aging dictator stubbornly maintained policies from a bygone era.

Even after suffering a debilitating stroke in 1968, Salazar continued to believe he governed Portugal. His ministers, remarkably, maintained this fiction, bringing him fake government papers to review.

This bizarre charade – where a man no longer in power thought he still ruled – perfectly symbolized Salazar’s disconnection from changing realities. His refusal to prepare for succession or reform his regime left Portugal unprepared for the inevitable transition, which came abruptly through military coup after his death.

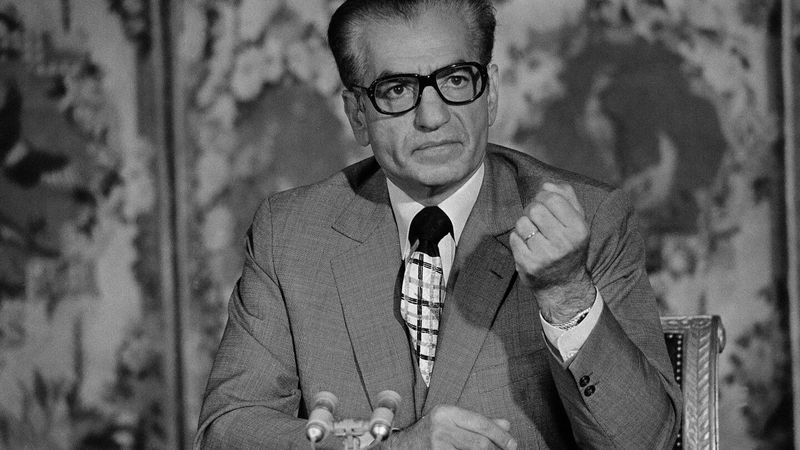

12. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi: Iran’s Tone-Deaf Monarch

As revolutionary pressure mounted in 1970s Iran, the Shah responded with a bewildering mix of concessions and crackdowns that satisfied nobody. Despite his Western education, he failed to understand the religious opposition brewing in his rapidly modernizing nation.

When protests erupted, the Shah vacillated between brutal suppression and sudden leniency. His notorious statement that he “heard the revolution” came far too late to implement meaningful reforms.

Even as his government crumbled, the Shah delayed crucial decisions about power-sharing. His final act – leaving Iran “for vacation” in January 1979 – epitomized his inability to face reality. This permanent departure without formal abdication created a power vacuum that revolutionary forces quickly filled.