Throughout history, power has corrupted even the closest family bonds. Some rulers, driven by paranoia, ambition, or the ruthless demands of leadership, made the chilling decision to execute their own flesh and blood. These royal family killings weren’t just personal tragedies—they shaped empires, altered succession lines, and revealed the darkest side of absolute power.

1. Qin Shi Huang (China, 259–210 BCE)

The first emperor of unified China didn’t hesitate to eliminate family threats. When his half-brother Chengjiao raised an army in rebellion, Qin Shi Huang’s response was swift and merciless.

The emperor, already known for his brutal efficiency, ordered Chengjiao’s immediate execution. This family purge was just one aspect of his ruthless leadership style that included burying scholars alive and creating the famous Terracotta Army to guard his elaborate tomb.

While Qin Shi Huang unified China and standardized everything from currency to written language, his paranoia about threats to his power ultimately led him to destroy anyone who challenged him—even his own brother.

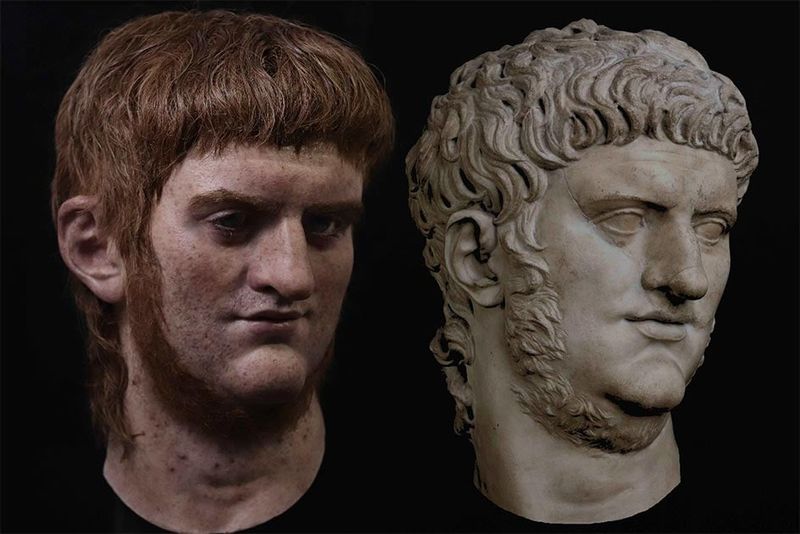

2. Emperor Nero (Rome, 37–68 CE)

Matricide marks one of history’s most notorious family betrayals. Nero, the troubled Roman emperor, ordered the assassination of his own mother, Agrippina the Younger, after she had schemed to place him on the throne.

Initially, Nero tried drowning her in a collapsible boat. When she survived by swimming to shore, he sent assassins to finish the job. Agrippina reportedly exposed her womb to her killers, telling them to stab the part that had given birth to such a monster.

Nero’s reign spiraled into tyranny after her death. He later kicked his pregnant wife to death and executed countless others before taking his own life as Rome turned against him.

3. Empress Wu Zetian (China, 624–705)

China’s only female emperor carved her path to power through family blood. Beginning as a concubine, Wu Zetian eliminated rivals with calculating precision, including her own sons who stood in her way.

She allegedly murdered her infant daughter and framed the empress, poisoned her eldest son Li Hong when he opposed her policies, and forced her second son Li Xian to commit suicide. Her ruthlessness extended to broader family purges, with nephews, cousins, and other potential threats systematically eliminated.

Despite this bloody legacy, historians acknowledge her administrative brilliance. Wu Zetian expanded Chinese territory, reformed government, and championed Buddhism while ruling effectively for decades—proving her deadly family sacrifices weren’t made in vain.

4. Henry VIII (England, 1491–1547)

The Tudor king’s marital body count makes him history’s most infamous husband. Henry VIII’s desperate quest for a male heir led him to execute two of his six wives on trumped-up charges of adultery, incest, and treason.

Anne Boleyn, mother of future Queen Elizabeth I, lost her head in 1536 after failing to produce a son. Catherine Howard, his fifth wife, met the same fate in 1542 for alleged infidelity. Henry’s bloodlust extended to distant cousin Margaret Pole, the elderly Countess of Salisbury, who was hacked to death by an inexperienced executioner.

While not directly murdering Elizabeth of York (his son’s mother), her suspicious death in childbirth raised eyebrows at court.

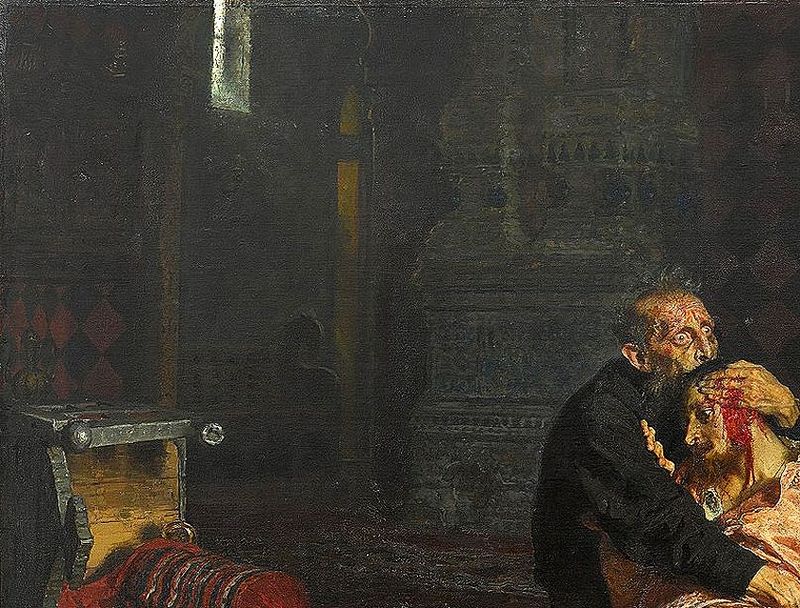

5. Ivan the Terrible (Russia, 1530–1584)

A single moment of rage forever changed Russian history. During a heated argument in 1581, Tsar Ivan struck his son and heir, Ivan Ivanovich, with his pointed staff, delivering a fatal blow to the head.

The tragedy plunged the already unstable tsar into profound grief. He repeatedly threw himself on his son’s coffin, wailing in anguish at what he had done. Artists have immortalized this moment of paternal regret in famous paintings like Ilya Repin’s masterpiece.

This family tragedy had lasting consequences for Russia. Without his capable heir, Ivan was succeeded by his unfit second son Feodor, leading to a period of chaos called the Time of Troubles that nearly destroyed the Russian state.

6. Sultan Mehmed III (Ottoman Empire, 1566–1603)

Royal succession in the Ottoman Empire came with a brutal price tag. When Mehmed III became sultan in 1595, he immediately ordered the execution of all nineteen of his brothers, some mere children, following a long-established Ottoman tradition called fratricide.

The brothers were strangled with silk bowstrings—a “privileged” death reserved for royalty that avoided spilling imperial blood. Their bodies were laid in rows before their weeping mother, who had watched all her sons die in a single day.

This institutionalized family slaughter wasn’t personal but political. Ottoman succession lacked primogeniture rules, meaning any brother could claim the throne, making these killings a coldly calculated insurance policy against civil war.

7. Emperor Kangxi (China, 1654–1722)

Kangxi’s reign stands among China’s most glorious, yet family tragedy shadowed his legacy. After naming his son Yinreng as heir, the emperor watched in growing horror as the prince’s behavior became increasingly erratic and violent.

Reports of Yinreng’s cruelty, sexual excesses, and plots against his father forced Kangxi’s hand. The heartbroken emperor deposed his son twice before finally imprisoning him permanently. Yinreng eventually died in his golden cage, never reconciling with his father.

Unlike many rulers who executed family members in cold blood, contemporary accounts suggest Kangxi genuinely struggled with this decision. He reportedly wept when signing the final order, calling it the most painful act of his sixty-year reign.

8. Peter the Great (Russia, 1672–1725)

The clash between Russia’s revolutionary tsar and his conservative son ended in tragedy. Alexei Petrovich opposed his father’s westernizing reforms, becoming a rallying point for traditionalists who wished to reverse Peter’s modernization of Russia.

When Alexei fled abroad seeking protection, Peter lured him back with promises of forgiveness. Instead, the tsar had his son imprisoned and tortured in the Peter and Paul Fortress. The exact circumstances remain murky, but Alexei died during interrogation—likely from wounds inflicted during torture sessions personally supervised by his father.

This family execution reveals Peter’s ruthless prioritization of his vision for Russia over blood ties. To him, his son represented the backward-looking Russia he was determined to transform, whatever the cost.

9. Empress Catherine the Great (Russia, 1729–1796)

Catherine’s rise to power began with a family betrayal drenched in blood. After seizing the Russian throne from her husband Peter III in a palace coup, Catherine claimed he died of “hemorrhoidal colic” just eight days later.

Few believed this convenient story. Historical evidence strongly suggests Catherine approved his murder, though she likely didn’t order it directly. Her lover Alexei Orlov and his brothers probably strangled the former emperor, eliminating any chance of counter-revolution.

Though technically not a direct execution, Catherine’s willingness to benefit from her husband’s convenient death set the tone for her pragmatic, sometimes ruthless reign. She transformed Russia into a major European power while carefully maintaining the fiction that her hands remained clean of imperial blood.

10. Sultan Mahmud II (Ottoman Empire, 1785–1839)

Ottoman throne politics often turned deadly, as Sultan Mahmud II demonstrated with chilling efficiency. Upon claiming the throne in 1808, he faced an immediate threat from his cousin, the recently deposed Sultan Mustafa IV.

Mahmud wasted no time ordering Mustafa’s execution, eliminating his primary rival in a single stroke. This familial execution wasn’t personal but followed the ruthless Ottoman political tradition that tolerated no competing claims to the throne.

Interestingly, Mahmud later broke with tradition by not executing his own brothers when he gained power. He instead instituted reforms that eventually ended the practice of royal fratricide, suggesting he recognized the brutality of a system that had nevertheless benefited his own rise to power.

11. King Christian VII (Denmark, 1749–1808)

Mental illness and court intrigue created a royal Danish tragedy. King Christian VII, suffering from severe mental health problems (likely schizophrenia), fell under the influence of his physician Johann Struensee, who became his wife Caroline Matilda’s lover and Denmark’s de facto ruler.

When political enemies exposed this arrangement, the king—manipulated by others—signed execution orders for Struensee. The queen’s lover was tortured with red-hot pincers before being beheaded and dismembered. Caroline Matilda, though spared execution because of her royal British connections, was divorced and exiled, never seeing her children again.

While technically not executing direct family, Christian’s actions destroyed his family through judicial murder and banishment, all while being too mentally impaired to fully understand what he was doing.

12. Emperor Jiaqing (China, 1760–1820)

Family purges sometimes extended beyond blood relations to encompass powerful in-laws and court favorites. When Emperor Jiaqing ascended the Qing throne, his first act was ordering the execution of Heshen, his father’s corrupt favorite who had married into the imperial family.

Heshen’s execution was particularly humiliating—he was forced to strangle himself with a silk cord while his vast, ill-gotten fortune was confiscated. Though not a direct blood relative, his elimination represented Jiaqing’s determination to purge corruption from his father’s reign.

Behind the scenes, however, court records suggest several extended imperial family members also disappeared during this transition of power. Their quiet eliminations followed a pattern familiar to many dynasties, where new emperors secured their position by removing potentially troublesome relatives.

13. Romanov Dynasty (Russia, 1613–1917)

The most famous royal family execution marked the end of a 300-year dynasty. Though not ordered by a family member, the Bolshevik execution of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, and their five children in July 1918 remains history’s most complete royal family annihilation.

The family was awakened at midnight and led to a basement room in Yekaterinburg, told they were being moved to safety. Instead, a firing squad opened fire, shooting even the young hemophiliac heir Alexei and his teenage sisters. When bullets failed to kill the children due to jewels sewn into their clothing, executioners used bayonets and rifle butts.

This brutal end to the Romanovs symbolized the revolutionary determination to eradicate all traces of the old order.