During World War II, behind closed doors and sworn to secrecy, thousands of women became the unsung heroes of Allied intelligence. While history books often highlight men like Alan Turing, female codebreakers played a crucial role in deciphering enemy communications, ultimately shortening the war by years. Their brilliance, dedication, and innovation not only helped defeat the Axis powers but also laid the groundwork for modern computing and cybersecurity.

1. Secret Army of 10,000+ Women at Bletchley Park

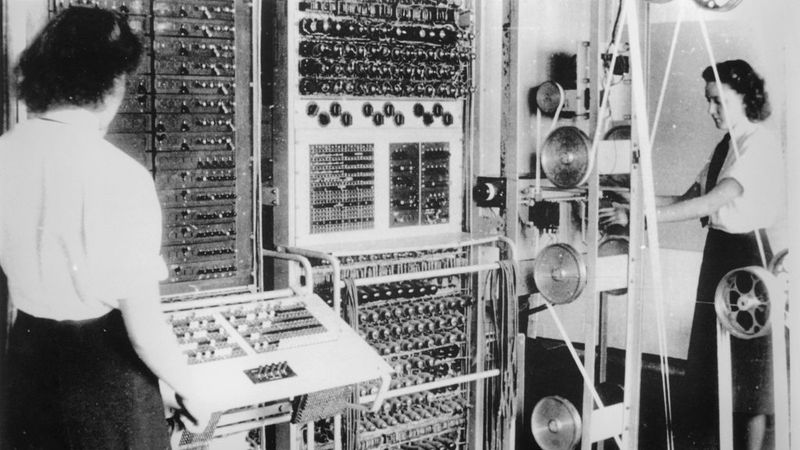

The famous British codebreaking headquarters employed over 10,000 women—roughly 75% of its entire workforce. These women came from all walks of life, from debutantes to schoolteachers.

Many arrived with degrees from prestigious universities like Oxford and Cambridge, while others demonstrated exceptional puzzle-solving abilities. Their roles ranged from operating the complex bombe machines to translating decrypted German messages and analyzing intelligence patterns.

Without this massive female workforce, Bletchley Park could never have processed the enormous volume of intercepted enemy communications that proved vital to Allied success.

2. Lifetime of Silence Under the Official Secrets Act

Upon joining Britain’s codebreaking operation, each woman signed the Official Secrets Act—a binding legal document forbidding them from discussing their work with anyone. Many couldn’t tell their husbands, children, or parents what they really did during the war.

This veil of secrecy continued for decades after WWII ended. Some women maintained their silence until the 1970s when information about Bletchley Park was finally declassified.

Imagine keeping such significant accomplishments hidden for a lifetime—many took their remarkable stories to their graves, never receiving public recognition for their world-changing contributions.

3. Joan Clarke: Brilliant Mathematician Paid Less Than Male Peers

Cambridge mathematician Joan Clarke worked alongside Alan Turing breaking the infamous Enigma code. Despite her exceptional abilities, the facility classified her as a ‘linguist’ rather than a cryptanalyst—a deliberate misclassification to justify paying her significantly less than male colleagues with identical responsibilities.

Clarke became deputy head of Hut 8, focused on naval ciphers, and received an MBE for her wartime service. Her relationship with Turing was portrayed in the film ‘The Imitation Game,’ though the movie took creative liberties with their actual history.

Despite gender discrimination, Clarke’s mathematical genius proved instrumental in cracking some of the war’s most challenging codes.

4. American WAVES: The U.S. Navy’s Female Codebreaking Force

Across the Atlantic, the U.S. Navy created WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), enlisting over 10,000 women for intelligence work. These remarkable women—many with backgrounds in mathematics, linguistics, and science—worked primarily at secret facilities in Washington D.C.

WAVES personnel tackled Japanese naval codes, including the notoriously difficult JN-25 cipher. Their cryptanalysis provided crucial intelligence about Japanese fleet movements, directly contributing to American victories in the Pacific theater.

The program represented the first time American women could serve in the Navy in roles other than nursing, opening doors for future generations of women in military intelligence.

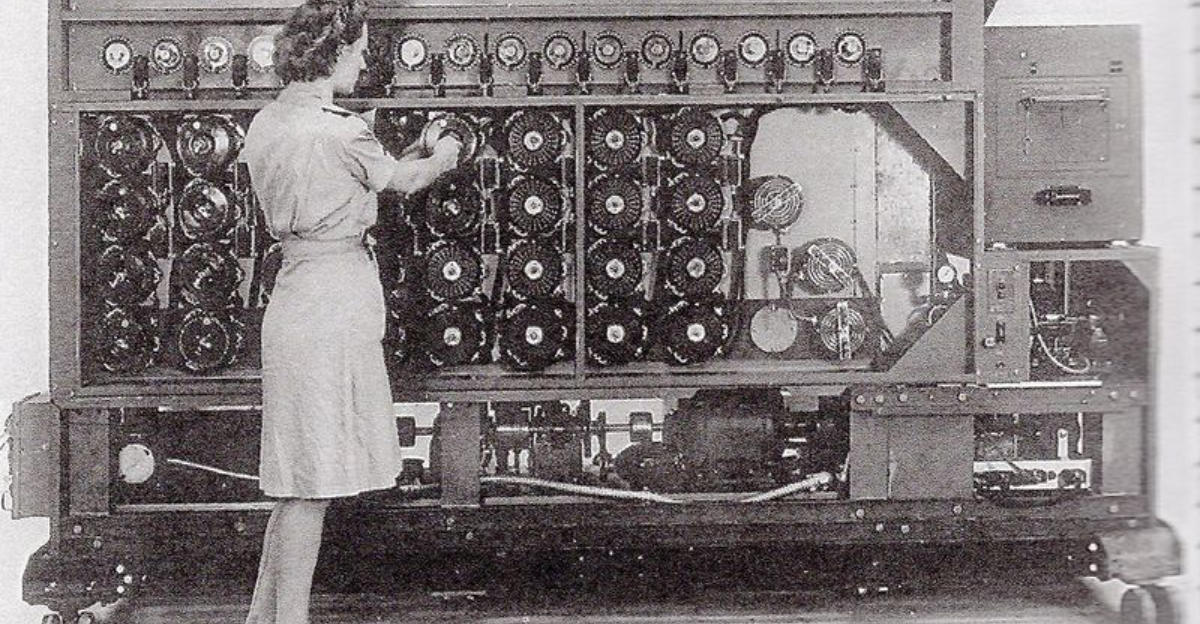

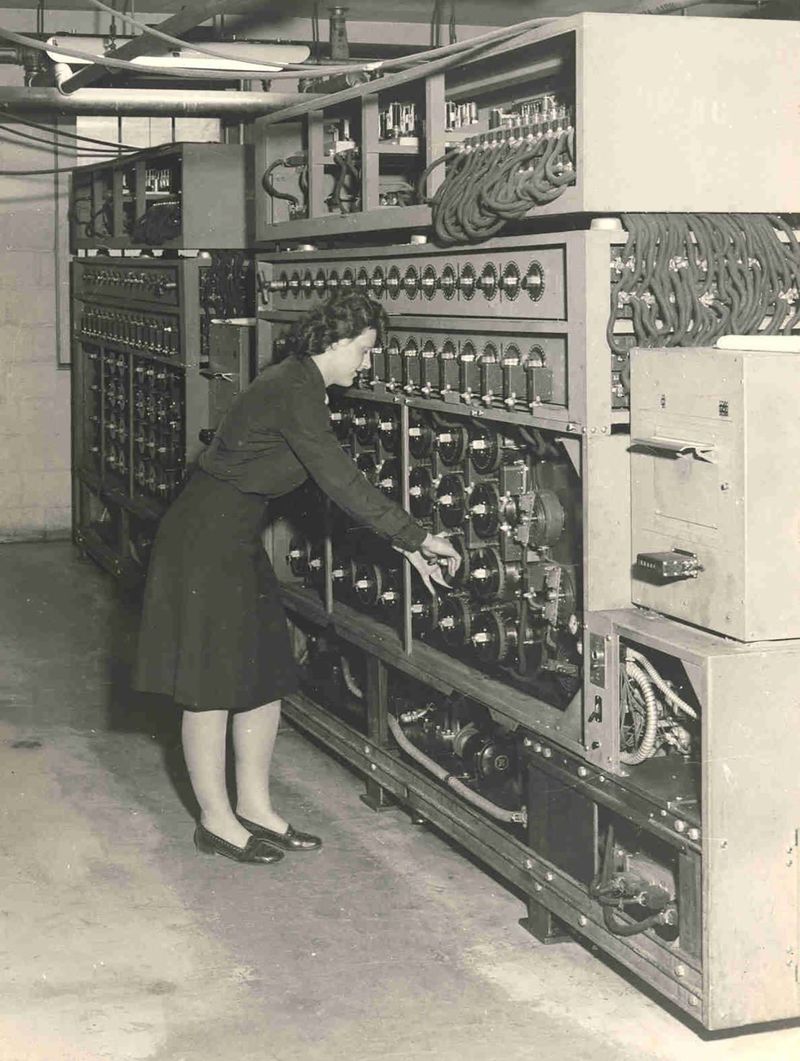

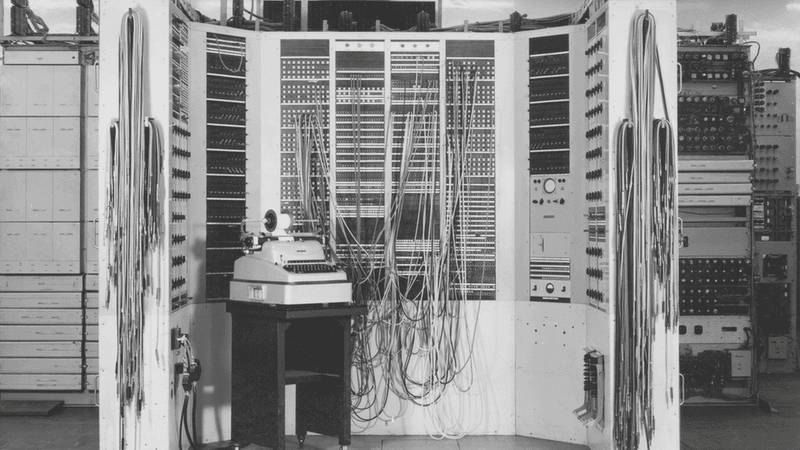

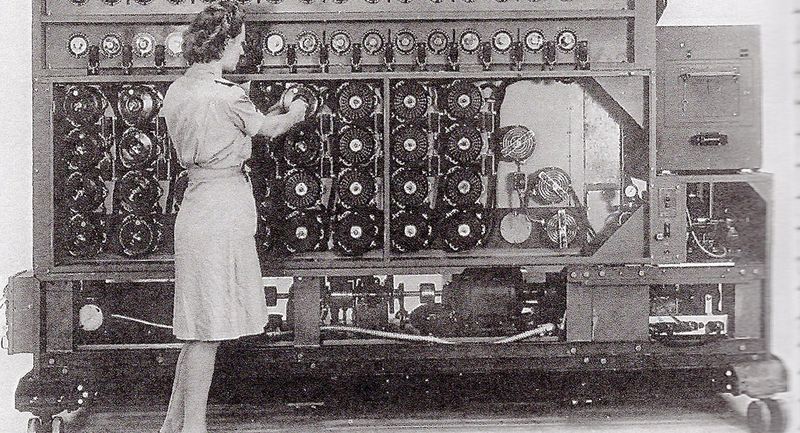

5. Pioneering Computer Programmers on the Colossus Machines

The Wrens (Women’s Royal Naval Service) operated Colossus—the world’s first programmable electronic digital computer—at Bletchley Park. These massive machines, designed to break the complex Lorenz cipher used by Hitler’s high command, required skilled operators to function properly.

Young women, typically in their late teens or early twenties, managed the delicate paper tapes, adjusted settings, and interpreted results. They became the world’s first computer programmers, developing techniques that would form the foundation of modern computing.

Without formal technical training, these women mastered cutting-edge technology through practical experience, creating procedural innovations still relevant to computer science today.

6. Crossword Puzzles as Secret Recruitment Tools

British intelligence devised an ingenious recruitment strategy—identifying potential codebreakers through newspaper crossword competitions. The Daily Telegraph ran special puzzles, and those who could complete them quickly received mysterious invitations to “contribute to the war effort.”

Many top solvers turned out to be women who demonstrated the perfect combination of lateral thinking, pattern recognition, and persistence needed for cryptanalysis. One famous competition in 1942 challenged readers to solve a difficult crossword in under 12 minutes—those who succeeded were discreetly approached about joining Bletchley Park.

This unconventional talent search brought brilliant female minds into the codebreaking operation who might otherwise have been overlooked.

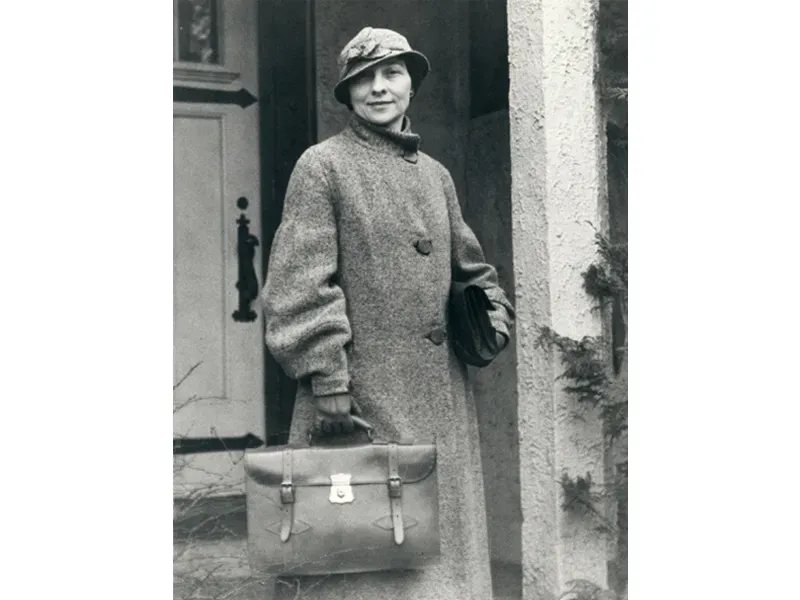

7. Elizebeth Friedman Dismantled Nazi Spy Networks Single-Handedly

American cryptanalyst Elizebeth Smith Friedman, often called “America’s first female cryptanalyst,” cracked complex codes revealing Nazi spy rings operating throughout South America. Her work exposed German agents communicating with U-boats and planning sabotage operations against Allied shipping.

Friedman’s discoveries led to dozens of arrests and disrupted Axis intelligence networks throughout the Western Hemisphere. Despite her extraordinary contributions, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover took public credit for these intelligence coups, and her role remained classified for decades.

Before the war, she had already made history by breaking alcohol smuggling codes during Prohibition and establishing the U.S. Coast Guard’s first cryptanalytic unit.

8. Post-War Dismissal Despite Superior Expertise

When victory bells rang in 1945, thousands of skilled female codebreakers faced an abrupt end to their careers. Despite years of specialized experience—expertise that couldn’t be taught in any university—most women were summarily dismissed to create positions for returning male soldiers.

The government discouraged them from pursuing further work in intelligence or the emerging computer field. Many returned to traditional roles as homemakers or took clerical positions far below their capabilities.

This mass dismissal represented an enormous brain drain, pushing pioneering women out of fields they had helped create and delaying women’s advancement in computing and cryptography for generations.

9. Battle-Changing Intelligence That Altered War’s Course

Female codebreakers directly influenced major military operations that determined the war’s outcome. Women in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park decrypted messages revealing German U-boat positions, helping Allied convoys avoid destruction and eventually winning the Battle of the Atlantic.

Their intelligence proved critical before D-Day, confirming that German high command had fallen for Allied deception plans. Without these interceptions, the Normandy landings might have faced much heavier resistance.

By some estimates, the work of these women shortened the war by two to four years, potentially saving millions of lives that would have been lost in a prolonged conflict.

10. Knitting Needles and Yarn: Unlikely Tools for Transporting Secrets

Female couriers developed creative methods to transport sensitive decoded information without arousing suspicion. Some ingeniously hid classified messages inside balls of yarn or knitting patterns, appearing as ordinary women with hobby materials rather than carriers of vital intelligence.

This technique proved especially effective for delivering information to Winston Churchill and military commanders. German intelligence often overlooked women as potential security threats, making female couriers particularly valuable for the most sensitive communications.

The stereotype of knitting as a harmless feminine activity provided perfect cover for these daring women who risked their lives carrying information that could determine the outcome of major military operations.

11. Ann Caracristi’s Critical Discovery in Japanese Encryption

Young cryptanalyst Ann Caracristi made a breakthrough that transformed America’s intelligence advantage in the Pacific. While analyzing intercepted Japanese Army communications, she identified a critical pattern in how they generated code keys, creating a vulnerability the Americans could exploit.

Her discovery allowed Allied forces to read thousands of Japanese military messages, providing advance warning of troop movements and battle plans. Caracristi’s brilliant analytical work saved countless American lives during Pacific island campaigns.

After the war, she continued her remarkable career, eventually becoming the first female Deputy Director of the National Security Agency in 1980—the highest position ever held by a woman in U.S. intelligence at that time.

12. Decades of Classification Delayed Recognition Until the 1970s

The extraordinary achievements of female codebreakers remained classified state secrets for over 30 years after WWII ended. While the public celebrated male war heroes, these women couldn’t even list their actual wartime roles on resumes or job applications.

When information about Bletchley Park was finally declassified in the 1970s, many of these pioneering women had already passed away or retired. Others were in their 70s or 80s before receiving any public acknowledgment for their contributions.

This extended classification created a significant gap in historical understanding, leading to decades where women’s critical role in Allied intelligence remained almost completely absent from history books and war memorials.

13. Foundations of Modern Computing and Cybersecurity

The techniques pioneered by female WWII codebreakers established fundamental principles still used in modern computing and cybersecurity. Their work on pattern recognition, statistical analysis, and machine processing of information created methodologies that directly influenced early computer science.

Women like Grace Hopper, who worked on early computing during the war, went on to develop the first compiler and helped create COBOL, a programming language still in use today. The punched card systems and logic processes developed for codebreaking evolved into core concepts for database design and information processing.

Every time we use encryption for secure online transactions, we’re benefiting from cryptographic principles these women helped establish decades ago.