The 1970s brought us some unforgettable TV fathers who were more flawed than fabulous. As society questioned traditional family values, television writers created dads who ranged from hilariously inept to downright problematic. These characters reflected changing attitudes about fatherhood while entertaining millions of viewers with their mistakes and missteps.

1. Archie Bunker’s Bigoted Blunders

Carroll O’Connor’s iconic character embodied everything wrong with stuck-in-the-past patriarchs. His constant racist remarks and sexist attitudes weren’t just uncomfortable—they actively damaged his relationship with daughter Gloria and son-in-law Michael.

Family gatherings at the Bunker household inevitably erupted into shouting matches when Archie’s outdated worldview collided with the progressive 1970s. While the show used his character to expose the absurdity of prejudice, Archie’s parenting approach left much to be desired.

Most cringe-worthy was his inability to show genuine affection, replacing emotional connection with gruff commands and dismissive nicknames like “Meathead” for his son-in-law. Despite occasional glimpses of growth, Archie remained television’s poster child for fatherly dysfunction.

2. George Jefferson’s Status-Obsessed Parenting

Sherman Hemsley portrayed a father who moved on up but left his parenting skills in the basement. George’s relationship with son Lionel centered more on appearances than genuine connection, using his child as another status symbol in his collection.

Quick with insults and slow with affection, George regularly undermined his son’s independence while simultaneously pushing him to succeed. His explosive temper and stubborn pride created unnecessary barriers between them.

The most painful moments came when George prioritized business deals and social climbing over Lionel’s emotional needs. Though the show played these failures for laughs, viewers witnessed a father whose ambition often eclipsed his parenting responsibilities—a cautionary tale about success at the expense of family bonds.

3. Fred Sanford’s Manipulative Maneuvers

Redd Foxx mastered the art of parental manipulation as junk dealer Fred Sanford. His famous clutching-the-chest routine—”It’s the big one, Elizabeth! I’m coming to join you, honey!”—wasn’t just a comedic bit; it was emotional blackmail designed to control his adult son Lamont.

Fred’s parenting toolkit contained insults, guilt trips, and schemes to keep Lamont tethered to the family business. When conventional manipulation failed, he’d resort to playing the helpless old man card, effectively sabotaging his son’s independence.

Behind the laughter lay a father unwilling to process his grief over his wife’s death or acknowledge his son’s need for autonomy. Though fiercely protective in his way, Fred’s self-centered approach to fatherhood left Lamont perpetually stuck between filial duty and personal freedom.

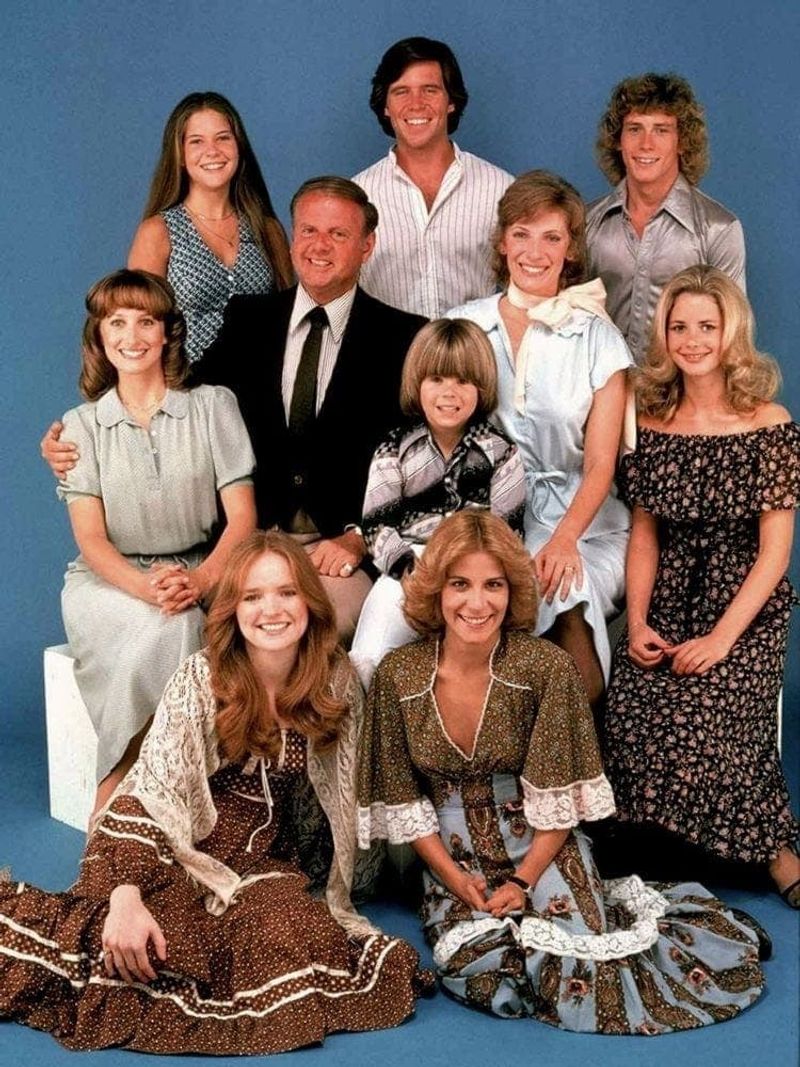

4. Tom Bradford’s Overwhelmed Oversight

Dick Van Patten portrayed the perpetually swamped patriarch of “Eight Is Enough” who demonstrated that quantity doesn’t equal quality in parenting. With eight children under one roof, Tom often retreated into his newspaper rather than tackling the emotional complexities of his brood.

Following his first wife’s death, Tom fumbled through single parenthood before remarrying, frequently delegating the heavy emotional lifting to his new wife Abby. His well-meaning but passive approach left children navigating significant life challenges with minimal guidance.

Most troubling was his inconsistent discipline—stern with some children while completely hands-off with others. Tom’s character served as a subtle warning about the consequences of emotional disengagement, even when physically present. His bewildered expressions became the visual shorthand for fathers drowning in family responsibilities.

5. Howard Cunningham’s Emotional Detachment

Tom Bosley’s “Mr. C” presented as the ideal 1950s father in this 1970s show, but his approach to parenting revealed significant blind spots. Despite his friendly demeanor, Howard remained emotionally distant from his children’s lives, retreating to his bathroom throne to read the newspaper whenever family tensions rose.

His son Richie faced numerous teenage challenges that Howard addressed with vague platitudes rather than meaningful guidance. Daughter Joanie received even less attention, while eldest son Chuck mysteriously vanished from the show without Howard seeming to notice.

The Cunningham patriarch embodied a generation of fathers who provided financially while remaining emotionally unavailable. His greatest parenting failure? Allowing local dropout Arthur Fonzarelli to become his children’s primary role model while he watched from the comfortable sidelines of his living room armchair.

6. Arthur Carlson’s Clueless Leadership

Gordon Jump portrayed the bumbling station manager of WKRP whose management style mirrored his approach to fatherhood: well-intentioned but hopelessly out of touch. His infamous turkey drop promotion—”As God is my witness, I thought turkeys could fly!”—perfectly encapsulated his decision-making abilities.

Though not technically a father to his staff, “The Big Guy” functioned as the station’s patriarchal figure, offering outdated wisdom and confused guidance. His inability to stand up to his domineering mother reflected his own stunted emotional development.

Behind his desk, Arthur played with toy trains rather than addressing station problems, avoiding conflict at all costs. His childlike naivety might have been endearing if it hadn’t repeatedly endangered his employees’ careers and sometimes their physical safety. Arthur represented fathers who never quite grew up themselves.

7. Dr. Arthur Harmon’s Condescending Commentary

Conrad Bain perfected the role of the insufferable know-it-all neighbor whose interactions with Maude’s family dripped with smug superiority. As husband to Maude’s best friend Vivian, Arthur regularly inserted himself into family matters with unsolicited advice steeped in outdated sexism.

His conservative views clashed spectacularly with Maude’s progressive household, creating uncomfortable moments when he attempted to lecture her daughter Carol on proper womanly behavior. Arthur’s pompous certainty about traditional gender roles made him the embodiment of patriarchal thinking that 1970s women were actively fighting against.

What made Arthur particularly cringe-worthy wasn’t just his opinions, but his absolute conviction in their correctness despite all evidence to the contrary. His character served as a cautionary tale about fathers who prioritize being right over being supportive or understanding.

8. Mike Brady’s Conflict-Avoiding Clichés

Robert Reed’s portrayal of the perfectly coiffed architect father looked ideal on paper but revealed serious flaws in practice. Behind Mike’s calm demeanor and ready-made speeches lurked a dad who avoided difficult conversations by papering over problems with greeting card platitudes.

When faced with genuine emotional turmoil among his six children, Mike retreated to his den to work on architectural drawings or delivered vague life lessons that rarely addressed the specific issue at hand. His famous study chats with the boys contrasted sharply with his hands-off approach to the girls’ problems, which he typically delegated to his wife Carol.

The Brady patriarch embodied the aesthetically perfect but emotionally shallow fatherhood that prioritized appearances over authentic connection. His greatest parenting sin? Making complex family dynamics seem solvable in 22 minutes with a smile and a catchphrase.

9. James Evans Sr.’s Explosive Temper

John Amos portrayed a hardworking father in Chicago’s housing projects whose fierce love for his family often manifested as intimidating anger. His catchphrase—”Damn, damn, DAMN!”—signaled impending emotional storms that left his children walking on eggshells.

James’ authoritarian parenting style reflected his determination to keep his children safe in a dangerous environment, but his explosive reactions created another kind of danger at home. His confrontations with son J.J. were particularly volatile, sometimes escalating to threats of physical discipline.

Though respected for his principles and work ethic, James’ inability to channel his frustrations constructively taught his children that anger was the appropriate response to life’s challenges. Behind his rage lay genuine fear for his family’s future, but his approach often undermined the very security he fought so hard to provide.

10. Lou Grant’s Newsroom Dictatorship

Edward Asner created an unforgettable character who transferred his personal frustrations into tyrannical newsroom management. Lou’s gruff exterior and bourbon-fueled leadership style made him more feared than respected among his journalistic “children.”

His approach to mentoring consisted primarily of barking orders and criticizing results without providing constructive guidance. Female journalists like Mary Richards faced particular challenges under Lou’s old-school management, as he struggled to adapt to women in professional roles.

What made Lou truly cringe-worthy was his emotional constipation—unable to express vulnerability or admit mistakes, he modeled toxic masculinity for an entire generation of viewers. Though occasionally showing glimpses of the caring man beneath the bluster, Lou’s default setting remained stuck on intimidation rather than inspiration, leaving his staff to seek emotional support from each other.

11. Walter Findlay’s Spineless Surrender

When faced with challenging parenting moments, Walter typically retreated to the liquor cabinet rather than engaging meaningfully. His pattern of withdrawal during family crises left Carol navigating life’s challenges without paternal guidance, while his drinking created additional problems rather than solving existing ones.

Walter’s most painful parenting failure was his tendency to undermine Maude’s parenting decisions behind her back, creating confusion about boundaries and expectations. Though occasionally standing up for himself in spectacular fashion, Walter’s day-to-day approach to family life modeled avoidance rather than engagement—hardly the example young Phillip needed.

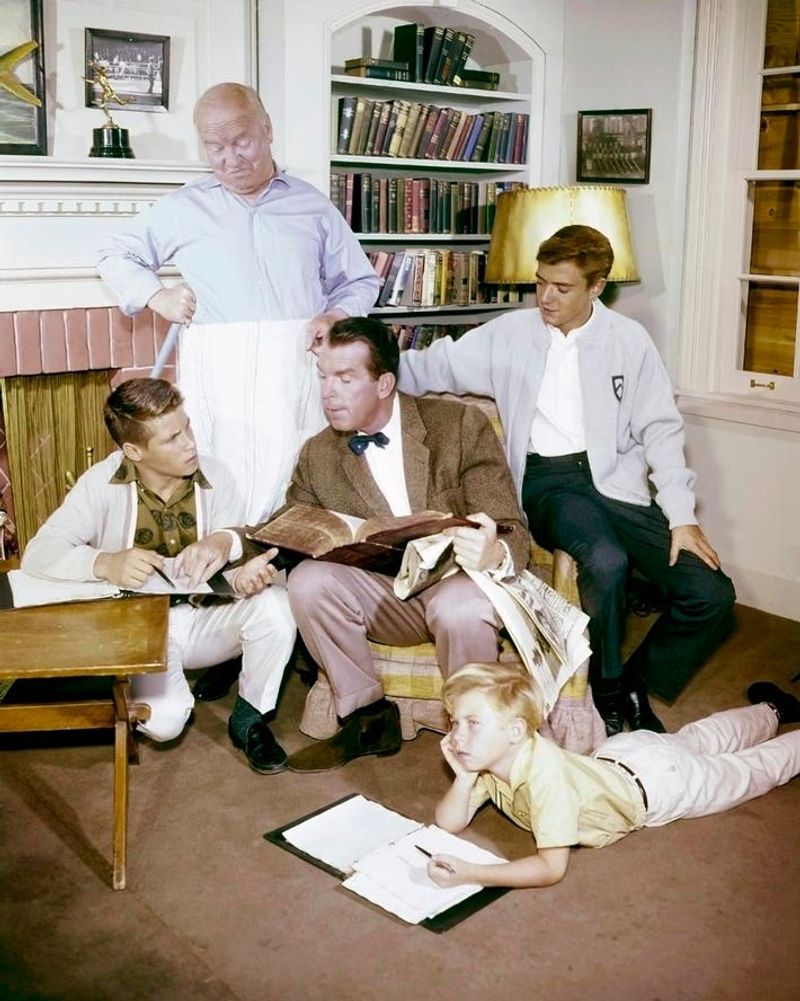

12. Steve Douglas’s Emotional Austerity

His reliance on housekeeper Uncle Charley and the boys’ great-uncle Bub for daily caregiving created an emotional distance that widened as his sons matured. When facing adolescent crises, Steve often retreated into his work, emerging only to deliver clinical advice devoid of genuine empathy.

Most troubling was Steve’s inability to discuss feelings—particularly grief over their mother’s death. This emotional austerity taught his sons to suppress rather than process their own emotions. Though the show continued into the early 1970s, Steve’s 1960s parenting style remained frozen in time, increasingly out of step with the era’s growing emphasis on emotional intelligence.

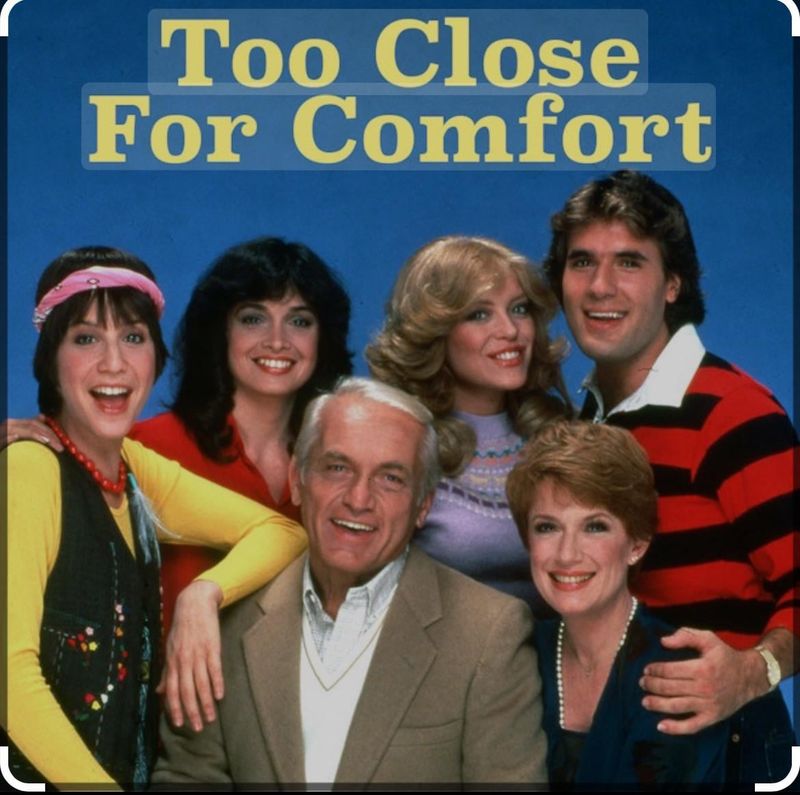

13. Henry Rush’s Boundary-Breaking Behavior

Henry’s cartoonist profession ironically highlighted his black-and-white thinking about appropriate behavior for his daughters. His constant unannounced visits to their apartment downstairs from his own revealed his inability to respect basic boundaries or privacy.

Most uncomfortable were Henry’s outdated views on dating and relationships, which he attempted to enforce through manipulation and guilt. His anxieties about his daughters’ sexuality manifested in intrusive behaviors that today would warrant a restraining order rather than a laugh track. Henry represented fathers who used concern as a justification for control.