Before becoming America’s first president, George Washington cut his teeth as a soldier in the French and Indian War. These early military experiences between 1754 and 1763 molded him into the commander who would later lead American forces to victory against Britain. His triumphs, failures, and lessons during this first war equipped him with the skills needed to win independence.

1. The Spark That Lit a Global Powder Keg

At just 22 years old, Washington inadvertently triggered an international conflict that would reshape world history. His 1754 ambush of French forces at Jumonville Glen escalated tensions between Britain and France to the breaking point.

Few young men have shouldered such momentous consequences. The skirmish taught Washington how small frontier actions could explode into global wars.

This hard-earned wisdom served him well during the Revolution, where he carefully weighed how American actions might affect potential French alliance or British response.

2. Lessons From Surrender at Fort Necessity

Smoke still hung in the air when Washington signed surrender papers at Fort Necessity in July 1754. Unaware of the French language, he accidentally confessed to assassinating a French diplomat—a humiliating mistake for the young officer.

Rain poured through the hastily built fort as his men suffered their first major defeat. This embarrassment left Washington permanently suspicious of European powers and their tactics.

The bitter taste of surrender strengthened his resolve never to be outmaneuvered diplomatically again, a caution that would serve him well when negotiating with France during the Revolution.

3. Becoming the Enemy’s Most Wanted

The French commanders branded Washington a villain after Jumonville Glen. Though no official bounty exists in historical records, French forces specifically targeted the young Virginian in subsequent engagements.

Imagine knowing enemy soldiers were hunting specifically for you! This experience shaped Washington’s visceral understanding of occupation and foreign military presence.

When British forces later occupied Boston and New York, Washington’s opposition wasn’t just political—it was personal. He had felt the weight of being hunted by a foreign army and knew precisely what American citizens faced under British occupation.

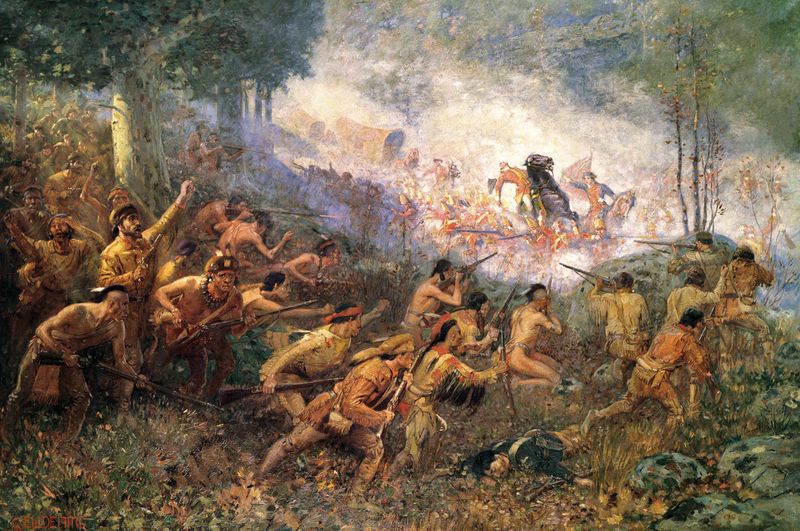

4. Survival Amid Braddock’s Bloody Defeat

Bullets whistled past Washington as he rode through chaos. General Braddock’s 1755 expedition against Fort Duquesne had collapsed into slaughter, with 456 British and colonial troops dead or wounded.

Washington had two horses shot from under him. Four bullet holes pierced his coat without touching his skin—a miracle that cemented his reputation for being divinely protected.

This catastrophe taught Washington the fatal flaws of European-style warfare in American terrain. During the Revolution, he would avoid Braddock’s mistakes, embracing mobility and terrain advantages rather than rigid formations that made perfect targets.

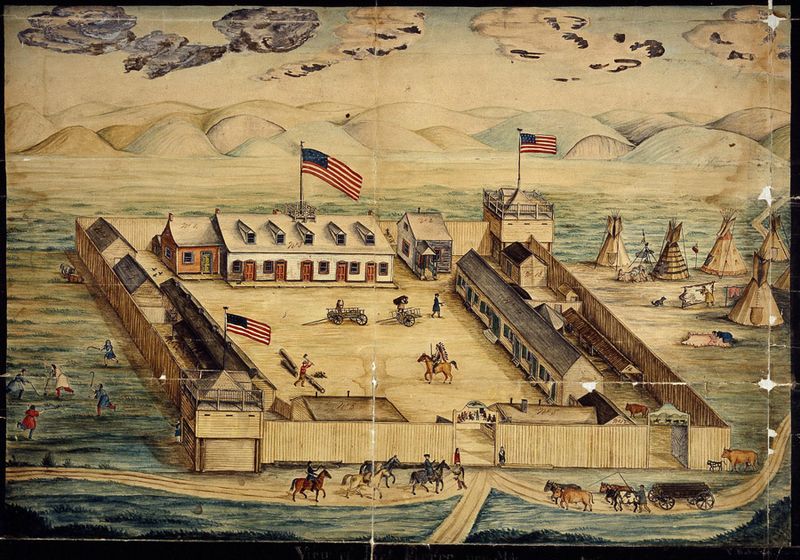

5. Creating a Defensive Masterplan

After witnessing Braddock’s bloodbath, Washington pioneered a new frontier defense strategy. Rather than marching columns of soldiers through forests, he established a network of forts along Virginia’s frontier, creating defensive strongpoints connected by mobile ranger units.

Colonial legislators balked at the expense. Yet Washington persisted, learning to balance military necessity with political reality—a skill that proved invaluable during the Revolution.

This early defensive mindset resurfaced years later at Valley Forge, where Washington chose strategic defense and preservation of forces over glorious but potentially disastrous offensives against superior British forces.

6. Founding America’s First Spy Network

Washington’s greatest weapon against the French wasn’t his musket—it was information. Commanding Virginia’s frontier forces, he recruited Native American scouts who provided crucial intelligence about enemy movements.

His letters reveal growing sophistication in gathering and analyzing intelligence. One dispatch to Governor Dinwiddie details French troop movements with remarkable precision, based on reports from his frontier spies.

This early experience spawned the Culper Ring—Washington’s Revolutionary War spy network. By the time he faced British forces, Washington had become America’s first spymaster, turning battlefield intelligence into a decisive advantage against numerically superior forces.

7. Mastering the Supply Chain Challenge

“No shoes, insufficient powder, and empty stomachs make poor soldiers.” Washington learned this brutal lesson commanding Virginia’s regiment during the French and Indian War.

Colonial legislatures constantly delayed funding. Washington’s personal letters reveal his frustration as his men went hungry and poorly equipped while bureaucrats debated budgets.

These early supply nightmares prepared him for the Revolution’s chronic shortages. When Continental soldiers later lacked shoes at Valley Forge, Washington drew on his frontier experience—organizing local production, appealing to civilian patriotism, and personally lobbying Congress with the persuasive skills honed in those earlier supply battles.

8. The Art of Strategic Retreat

Washington lost more battles than he won during the French and Indian War. Yet these defeats contained the seeds of future victory as he mastered the strategic retreat—preserving his forces to fight another day.

After one particularly difficult withdrawal, Washington wrote: “We shall learn to beat them finally, by being beaten often.” This resilience became his trademark during the Revolution’s darkest hours.

When forced to abandon New York in 1776, Washington executed a masterful withdrawal that saved the Continental Army from destruction. This wasn’t luck—it was a skill cultivated through painful experience on earlier frontiers.

9. Feeling the Sting of British Prejudice

Despite risking his life alongside British regulars, Washington faced constant reminders that colonials were second-class soldiers. British officers refused him a royal commission, regardless of his battlefield accomplishments.

“The distinction between a Royal officer and a Provincial officer is immense,” Washington wrote bitterly to his brother in 1756. Even when commanding hundreds of men, he ranked below British lieutenants fresh from England.

This systematic disrespect planted revolutionary seeds. When British generals later dismissed American fighting abilities during the Revolution, Washington knew their arrogance firsthand—and how to exploit it on the battlefield.

10. Meeting Future Revolutionary Figures

The French and Indian War served as a strange reunion preview. Washington campaigned alongside men who would later become key figures in the American Revolution—both allies and enemies.

Thomas Gage, who later commanded British forces at Lexington and Concord, served with Washington under Braddock. Horatio Gates, Washington’s future rival, was a British officer during the same campaigns.

Charles Lee, another future Revolutionary general, fought in the same forests. These shared experiences created complex personal dynamics that would influence Revolutionary War strategy and politics—Washington knew his opponents’ thinking because he had once shared tents and battlefields with them.

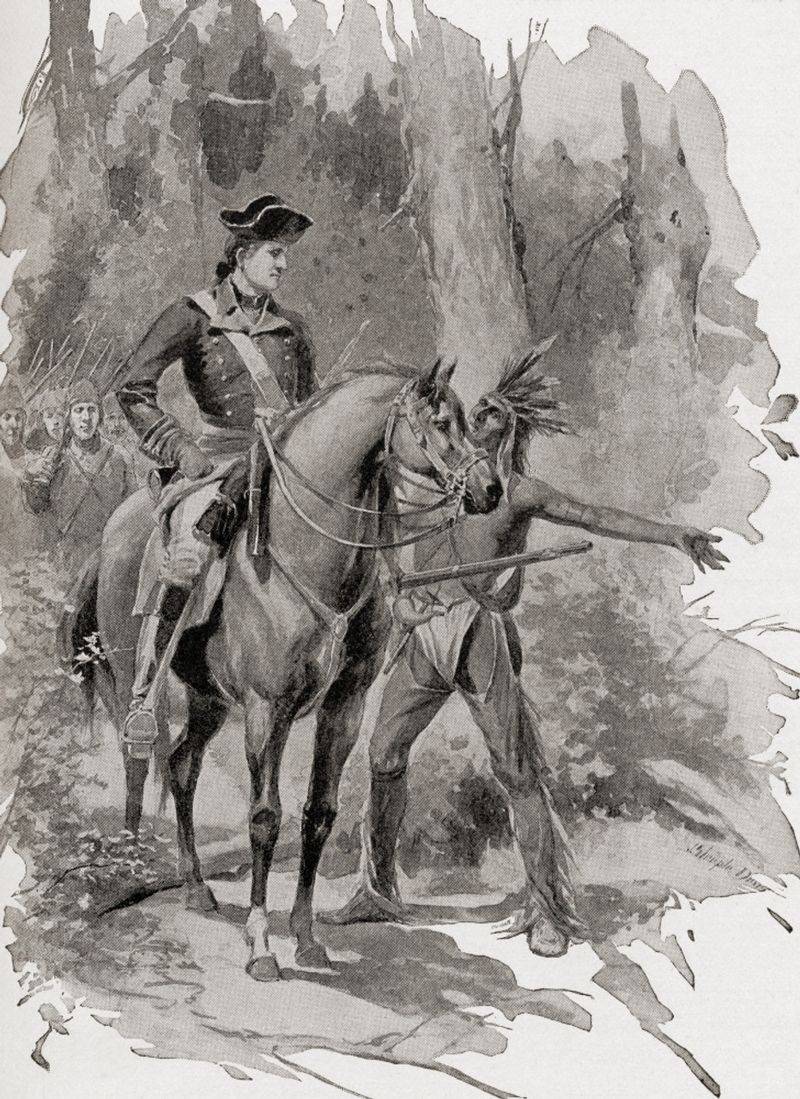

11. Learning Native American Diplomacy

Washington’s early encounters with Native American tribes were often clumsy. Yet these frontier negotiations taught him crucial lessons in cross-cultural diplomacy that would serve the Revolution.

After one particularly difficult council with Iroquois leaders in 1758, Washington noted the importance of respecting their customs rather than imposing European diplomatic protocols. He learned to listen before speaking—a rare quality among colonial leaders.

During the Revolution, Washington’s frontier-forged diplomatic skills helped secure crucial Native neutrality in key campaigns. While his approach wasn’t perfect, his respect for tribal sovereignty exceeded most contemporaries.

12. Surviving Against Impossible Odds

Four musket balls through his coat. Two horses shot from under him. Countless near-misses that should have ended his life. Washington’s repeated survival during the French and Indian War seemed beyond mere luck.

A Native American prophecy emerged: “The Great Spirit protects this man. He cannot be killed in battle.” Even Washington’s enemies began believing he possessed supernatural protection.

This reputation for divine favor followed Washington into the Revolution. When bullets again missed him during later battles, soldiers saw confirmation of his destiny to lead America to independence—a psychological advantage that bolstered troop morale during the darkest revolutionary moments.

13. Witnessing the Power of Colonial Unity

Before the Albany Congress proposed colonial union, Washington experienced military cooperation firsthand. Virginia troops fought alongside Pennsylvania militias and New York forces—a practical demonstration that colonies could unite effectively.

“When joined in common cause, the colonies possess remarkable strength,” Washington wrote after observing multi-colony operations in 1758. This lesson stayed with him.

Later, as commander-in-chief, Washington insisted on a truly continental army rather than separate state forces. His vision for American military unity grew directly from seeing colonial cooperation during his first war—a practical federalism forged in frontier combat years before the Constitutional Convention.