Marriage in the Middle Ages was nothing like the love-based unions we think of today. From arranged matches to property exchanges, medieval matrimony followed strict rules that shaped society for centuries.

These customs might seem strange to modern eyes, but they reveal fascinating insights about how our ancestors viewed family, love, and commitment.

1. Love Wasn’t a Requirement

Medieval marriages resembled business deals more than romantic partnerships. Families arranged unions to gain land, forge political alliances, or climb the social ladder. Children had little say in their marital future.

Romantic love was actually viewed with suspicion and considered a form of madness! Literature might celebrate passionate love stories, but real-life couples were expected to develop affection after marriage, not before.

The concept of marrying for love gradually emerged in the later Middle Ages, though it remained rare until much later centuries.

2. Marriages Were Often Arranged in Childhood

Imagine having your life partner chosen when you were still playing with toys! Noble families frequently betrothed their children as young as 5 or 6 years old to secure advantageous connections.

These child betrothals weren’t just suggestions – they were binding contracts sealed with legal documents and sometimes ceremonies. The actual marriage ceremony might be delayed until the children reached puberty.

Young Eleanor of Castile was only 13 when she married the future King Edward I of England, following an arrangement made years earlier – a typical royal match of the era.

3. Girls Could Marry at 12, Boys at 14

The Church established marriage age minimums that seem shockingly young by modern standards. Girls could legally wed at just 12 years old, while boys had to wait until 14.

These ages weren’t arbitrary – they roughly corresponded to when children reached puberty in medieval times. Physical maturity was considered more important than emotional readiness.

Many noble girls were married off immediately upon reaching the minimum age, especially if valuable alliances were at stake. Peasant families often waited longer, until their daughters were in their late teens and better able to manage household responsibilities.

4. Consent Was Technically Required — But Rarely Respected

Church law insisted that both bride and groom must freely consent to marriage – a surprisingly progressive stance for the time. The reality, however, rarely matched this ideal.

Family pressure, economic necessity, and social expectations created an environment where refusing a match could lead to punishment or disinheritance. Many young people, especially women, had no practical way to say no.

Silent consent was often enough – if a bride didn’t actively protest during the ceremony, officials assumed she agreed. Some girls were even drugged or threatened to ensure their compliance with unwanted marriages.

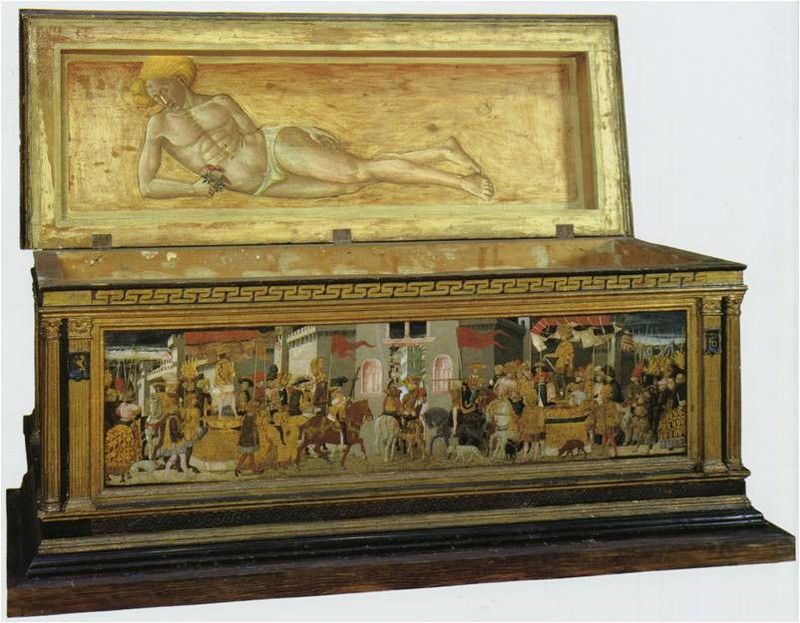

5. Dowries Were Everything

The dowry system dominated medieval marriages, requiring a bride’s family to provide substantial assets to her new husband. For wealthy families, these payments could include land, properties, jewelry, furniture, and even rights to collect taxes!

A generous dowry could help a woman secure a better match and provide her with some security if widowed. Poor families struggled to gather even modest dowries, sometimes delaying marriages for years.

Italian merchant families kept detailed dowry records, with some payments worth multiple years of a merchant’s income – a massive financial sacrifice to secure advantageous marriages for their daughters.

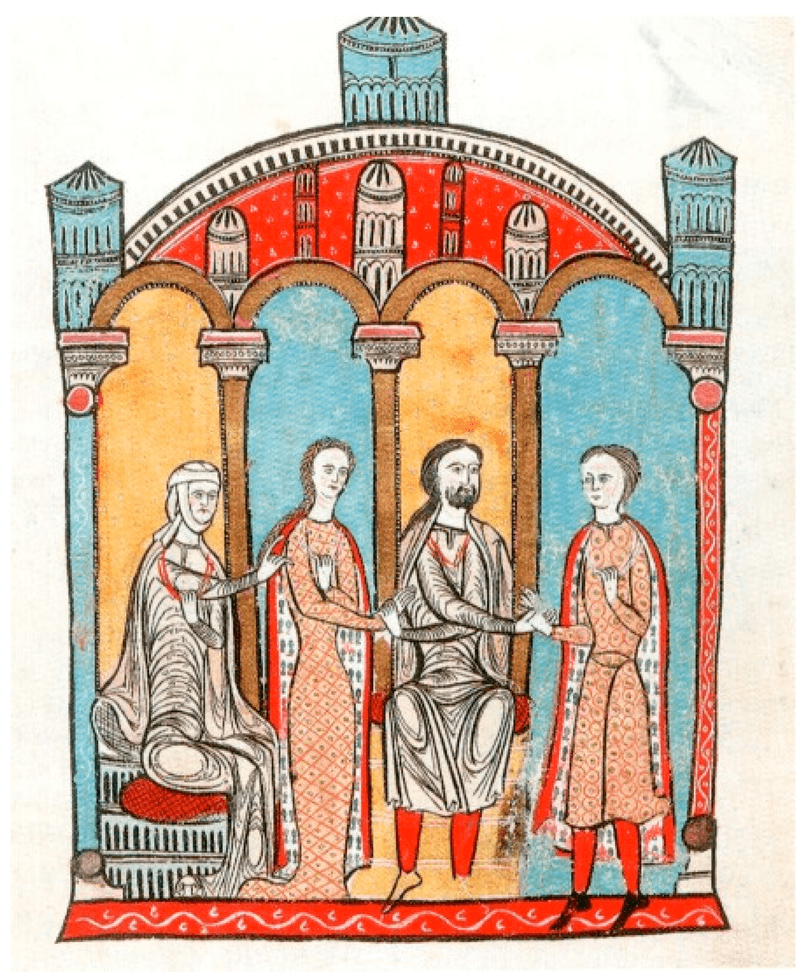

6. Marriage Was a Legal Contract, Not a Religious Ceremony

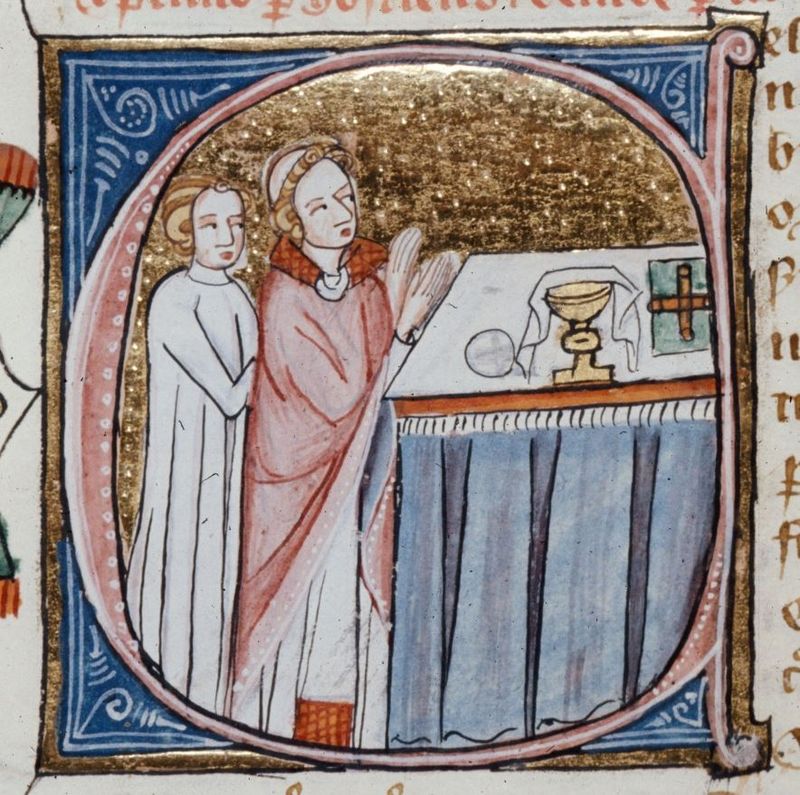

Surprising fact: for most of the early Middle Ages, marriage was primarily a civil arrangement! Two people could legally wed by simply declaring their intent to marry and exchanging consent – no priest required.

The Church gradually increased its authority over marriage during the 12th century. The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 finally established marriage as an official sacrament requiring church oversight.

Even after this change, “clandestine marriages” remained common and legally binding until the 16th century. A couple could marry by exchanging vows privately, though this often created inheritance disputes that kept medieval courts busy.

7. Weddings Didn’t Always Happen in Churches

Medieval weddings weren’t confined to church buildings as we might expect. Many ceremonies took place outdoors on church steps, in village squares, or even at local taverns!

The actual location mattered less than having witnesses who could verify the couple’s consent. Wealthy nobles might celebrate elaborate cathedral weddings, while peasants often married wherever was convenient for their community.

Marriage celebrations typically involved the entire village or town in feasting and merrymaking. Even humble weddings featured special foods, music, and dancing that might last for days – a rare break from the hardships of medieval life.

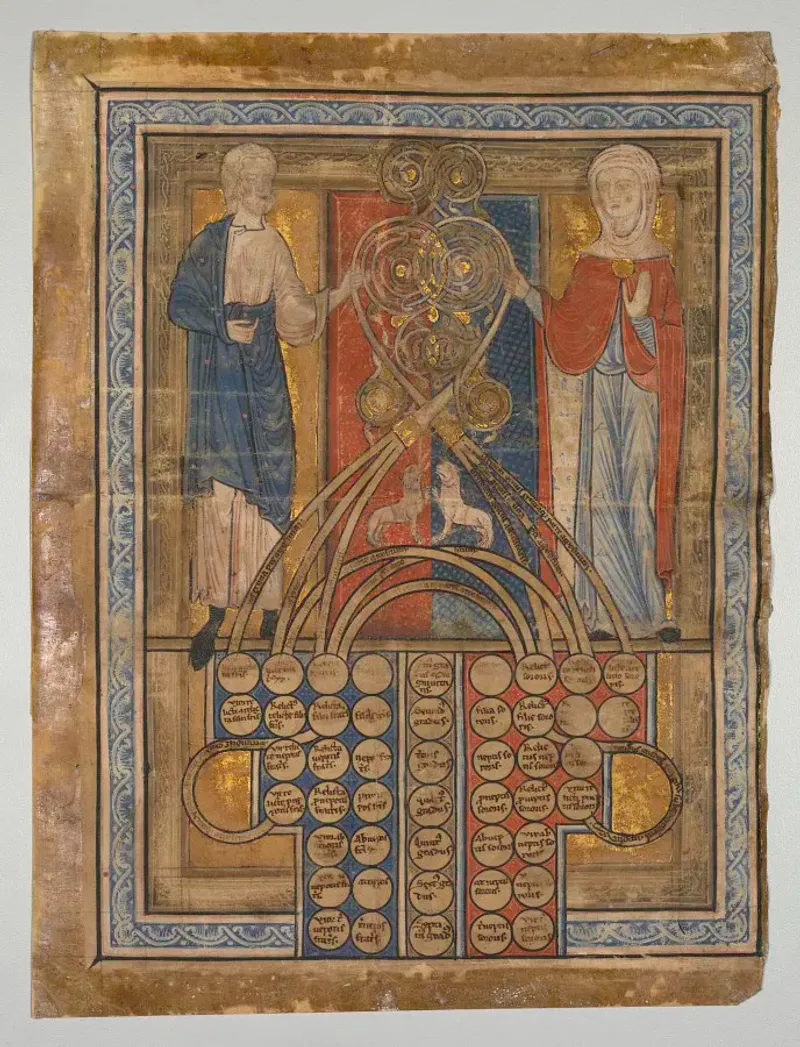

8. First Cousins? Totally Allowed (At First)

Marriage between cousins wasn’t just permitted in early medieval society – it was sometimes encouraged! Royal and noble families frequently married relatives to keep property within the family and strengthen bloodlines.

The Church gradually expanded marriage prohibitions, eventually banning unions between couples related within seven degrees of kinship. This created an absurdly wide restriction that theoretically prevented marriage between sixth cousins!

In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council reduced the prohibition to four degrees (third cousins), making family trees slightly less complicated. Wealthy families who wanted to break unwanted marriages often suddenly “discovered” previously unknown family connections.

9. Annulments Were a Noble Luxury

When King Henry VIII famously sought to end his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, he was following a long tradition of powerful nobles using annulments as medieval “divorces.” Unlike commoners, the wealthy could petition Rome directly with generous “gifts” to speed the process.

Claiming consanguinity (blood relation) was the most popular excuse, even when the relationship was extremely distant. Other grounds included non-consummation, previous vows, or forced consent.

Common people rarely had access to annulments due to the complex legal process and prohibitive costs. A peasant woman stuck in an abusive marriage had virtually no escape, while nobles could dissolve unions that no longer served their interests.

10. Wives Became Their Husband’s Property

The legal concept of “coverture” erased a married woman’s independent legal identity. Upon saying “I do,” a wife’s property, earnings, and even her body legally belonged to her husband.

A medieval wife couldn’t own property independently, sign contracts, or bring lawsuits without her husband’s permission. Her husband could legally “correct” her behavior through physical discipline that would be considered domestic abuse today.

Some clever women worked around these restrictions through special legal arrangements called “femme sole” status, allowing them to conduct business. This exception helped widows and wives of absent merchants maintain livelihoods when male protection disappeared.

11. Infidelity Laws Were Deeply Unequal

Medieval society maintained a stark double standard regarding marital faithfulness. A wife’s adultery was considered a grave crime that threatened family bloodlines and inheritance – punishable by public humiliation, confinement in a convent, or even death.

Meanwhile, husbands routinely kept mistresses with minimal social consequences. Only if a man’s affairs caused public scandal or involved another nobleman’s wife would he face serious repercussions.

Court records from medieval London reveal women paraded through streets wearing special headgear marking them as adulterers, while their male partners often escaped with minor fines or brief imprisonment.

12. Marriage Boundaries Were Blurred with Religion

The medieval Church preached clerical celibacy, but reality often looked quite different. Many village priests lived openly with female companions, sometimes called “housekeepers” but functioning as wives in all but name.

Before serious reforms in the 11th century, some clergymen even married officially. Pope Gregory VII strengthened celibacy requirements around 1075, but enforcement varied widely across Europe.

Parish records reveal communities often accepted priest-wife arrangements as normal, with children of these unions sometimes following their fathers into Church careers. Only when Church authorities conducted formal visitations would these relationships be temporarily hidden or penalized.

13. Divorce Was Nearly Impossible

Medieval marriages were meant to last until death – literally. The Church considered marriage an unbreakable sacrament, leaving annulment as the only escape route.

Unlike modern divorce, annulment didn’t end a valid marriage but declared it had never existed at all. Proving grounds for annulment required witnesses, documentation, and often political connections.

Abandoned spouses faced terrible dilemmas – they couldn’t remarry without proof their first spouse had died, leading to a limbo status called “half-marriage.” Some desperate people resorted to bigamy, risking severe punishment if discovered. Others simply lived apart while technically remaining married for decades.

14. Childbearing Was a Marital Duty

A medieval wife’s primary purpose was producing heirs – particularly sons. Royal marriage contracts sometimes specifically mentioned the expectation of children, with some even including clauses about returning dowries if the bride proved barren.

Women endured tremendous pressure and dangerous childbirth conditions to fulfill this duty. Queen consorts lived under constant scrutiny until they produced male heirs, regardless of how many daughters they bore.

Fertility remedies ranged from prayers to saints specializing in conception to bizarre herbal concoctions and magical rituals. Blame for childlessness fell almost exclusively on women, despite modern understanding that male factors contribute to half of infertility cases.

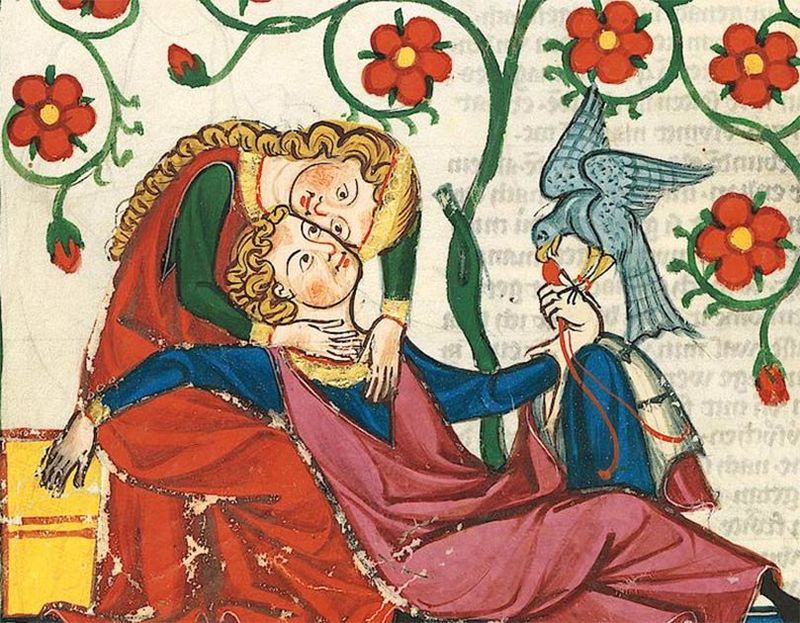

15. There Were Still Real Love Stories

Amid all these practical arrangements, genuine love stories still blossomed in medieval marriages. Personal letters between long-married couples reveal deep affection that developed over years of partnership.

The 12th-century French noblewoman Héloïse and her tutor Abelard defied social norms with their passionate romance and secret marriage. Their surviving love letters show emotional depth that rivals any modern romance.

Margery Kempe’s 15th-century autobiography describes her negotiation with her husband for a chaste marriage after bearing 14 children – showing that even within strict medieval frameworks, couples found ways to redefine their relationships based on mutual understanding.