The Declaration of Independence marks America’s bold claim to freedom in 1776. This historic document, with its elegant prose and powerful ideals, changed the course of history forever. Behind those famous words lie surprising stories, hidden details, and quirky facts that most Americans never learned in history class.

1. Wrong Date Celebration

Americans celebrate Independence Day on the wrong date! While July 4th commemorates when Congress approved the final text, most delegates actually signed the document on August 2, 1776.

This month-long gap created a strange situation where America declared independence before most representatives had formally committed their signatures. Some delegates didn’t sign until months later, and a few never signed at all.

The tradition of July 4th celebrations began the following year with bonfires, bells, and fireworks, establishing a precedent that continues today.

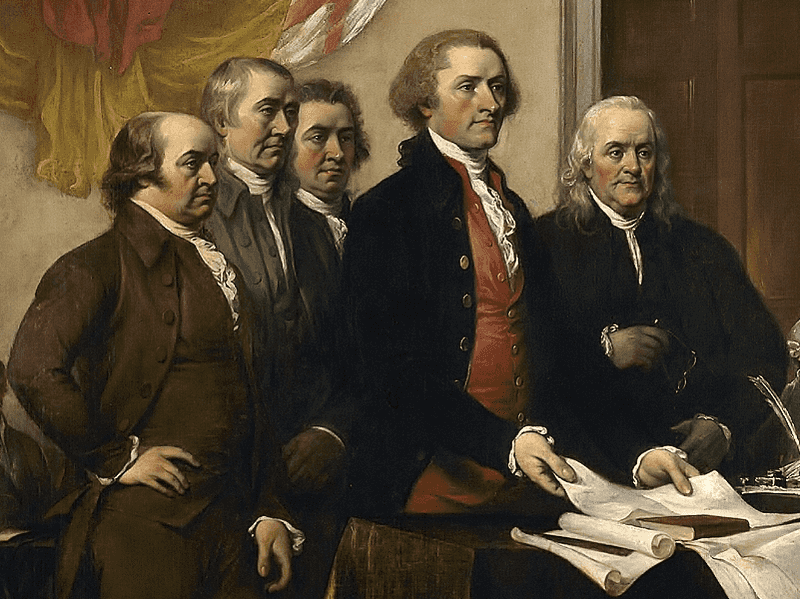

2. Five-Man Writing Committee

Thomas Jefferson gets most of the credit, but crafting the Declaration was a team effort. Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” – Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston – to draft the document.

Jefferson produced the initial draft, then the committee made revisions before presenting it to Congress. The full Congress then made 86 additional changes, cutting nearly a quarter of Jefferson’s text.

Jefferson was actually the committee’s second choice as primary writer. Adams declined the honor, believing Jefferson’s writing skills and Virginia roots would better unite the colonies.

3. Anti-Slavery Passage Removed

Jefferson’s original draft included a passionate paragraph condemning slavery as a “cruel war against human nature.” The passage explicitly blamed King George III for forcing the slave trade upon the colonies against their wishes.

This section was completely removed during congressional edits to appease Southern slaveholding colonies. Without this compromise, the Declaration would never have received unanimous approval.

The irony wasn’t lost on Jefferson, who owned over 600 enslaved people during his lifetime. This early moral compromise foreshadowed the difficult struggle America would face over slavery for the next century.

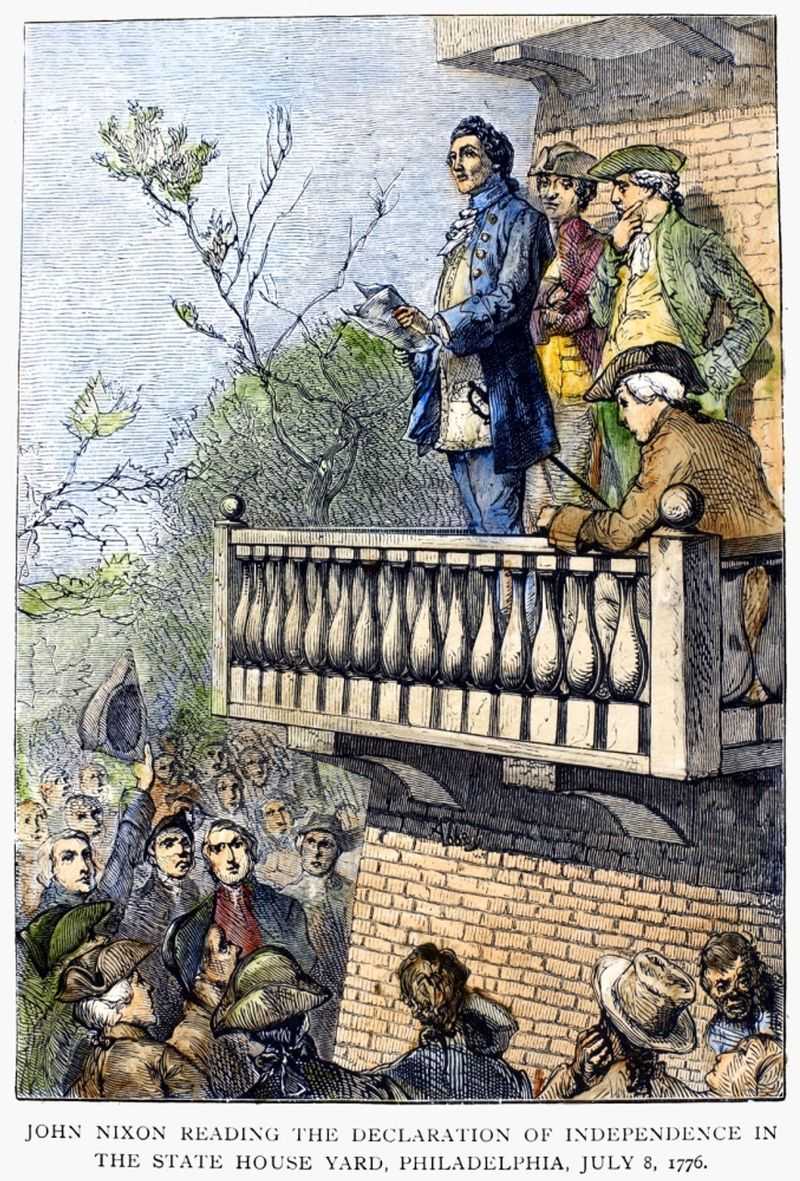

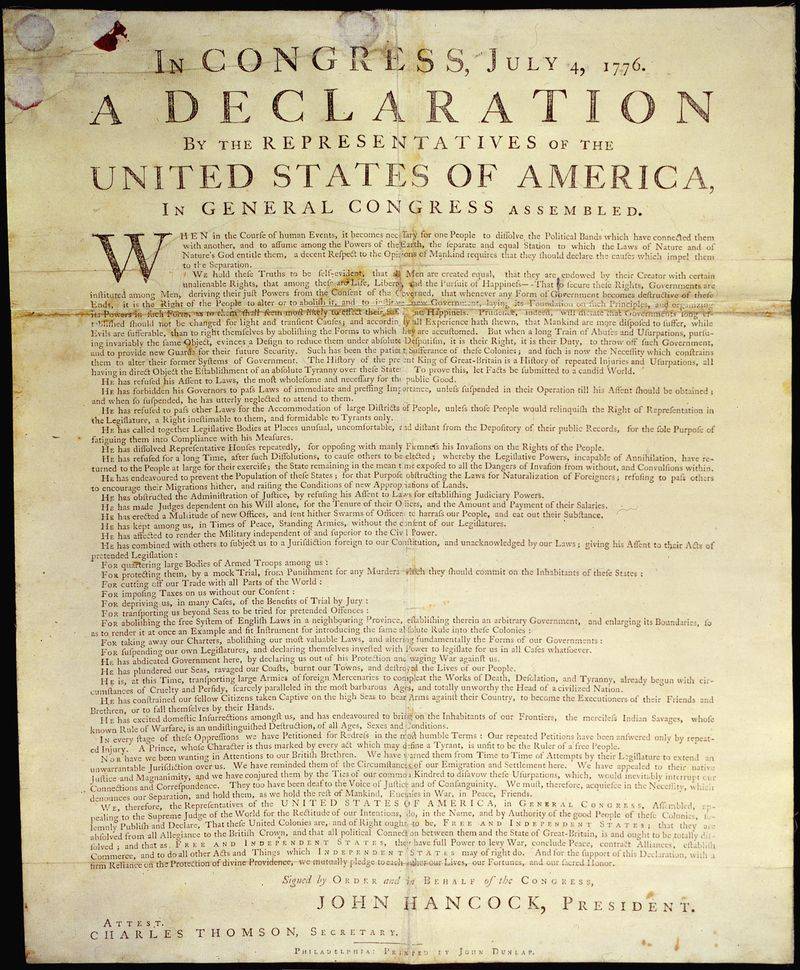

4. Delayed Public Announcement

After Congress approved the Declaration on July 4th, they didn’t immediately broadcast it to the world. The text needed to be formatted, printed, and distributed – no small task in 1776!

Philadelphia printer John Dunlap worked through the night producing what are now called “Dunlap Broadsides.” The first public reading didn’t occur until July 8th in Philadelphia’s Independence Square, where crowds cheered and the Liberty Bell reportedly rang.

George Washington had the Declaration read to his troops in New York on July 9th, inspiring soldiers who faced imminent battle with the British. Many Americans didn’t hear the news until weeks later.

5. Presidential Signers Club

Only two men who signed the Declaration later became President of the United States: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Both died on July 4, 1826 – exactly 50 years after the Declaration’s adoption – in one of history’s most remarkable coincidences.

Adams’ last words reportedly were: “Thomas Jefferson survives.” He was wrong – Jefferson had died hours earlier.

George Washington, though presiding over the Constitutional Convention that created the Declaration, couldn’t sign it because he was already leading the Continental Army in New York. James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution,” was too young and not yet in Congress.

6. Age Extremes Among Signers

The Declaration’s signers spanned an impressive age range. Benjamin Franklin, at 70, brought elder statesman wisdom to the revolutionary cause. His scientific fame and diplomatic experience lent crucial credibility abroad.

At the opposite end, South Carolina’s Edward Rutledge was just 26 when he signed – younger than many college graduates today. Between these bookends, most signers were middle-aged professionals: lawyers, merchants, and landowners with much to lose.

The average age was 44 – remarkably similar to today’s average age in Congress. This blend of youthful energy and seasoned experience helped forge America’s revolutionary vision.

7. Signer Who Took It Back

Richard Stockton of New Jersey became the only signer to renounce his signature. Captured by the British in November 1776, he endured brutal prison conditions in New York, including starvation and exposure to freezing temperatures.

Under duress, Stockton signed an oath of allegiance to King George III to secure his release. His home was looted, his library burned, and his health permanently damaged by his imprisonment.

Though many condemned his recantation, Congress eventually restored his reputation. Stockton’s ordeal highlights the very real dangers signers faced – they weren’t just risking political careers but their lives, families, and fortunes.

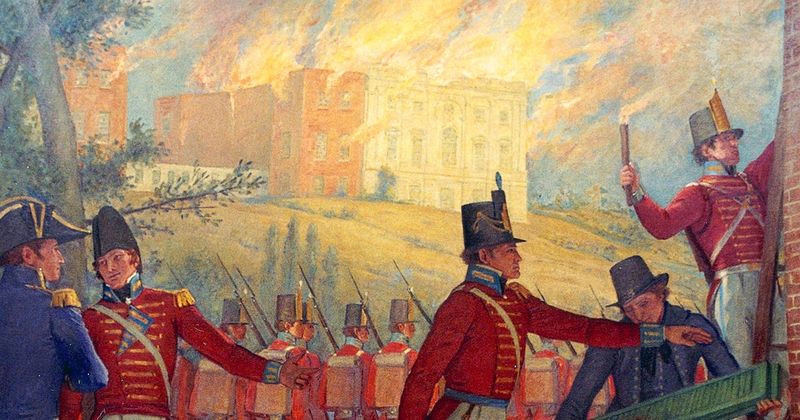

8. War of 1812 Rescue Mission

During the War of 1812, quick thinking saved the Declaration from British hands. As enemy troops approached Washington in August 1814, State Department clerk Stephen Pleasonton recognized the danger to America’s founding documents.

Pleasonton gathered the Declaration, Constitution, and other precious records. He packed them in linen bags and transported them to an abandoned gristmill in Virginia countryside.

His actions proved prescient when British forces burned the White House and Capitol days later. Without Pleasonton’s emergency evacuation, these irreplaceable documents might have been destroyed, leaving America without the physical embodiment of its founding principles.

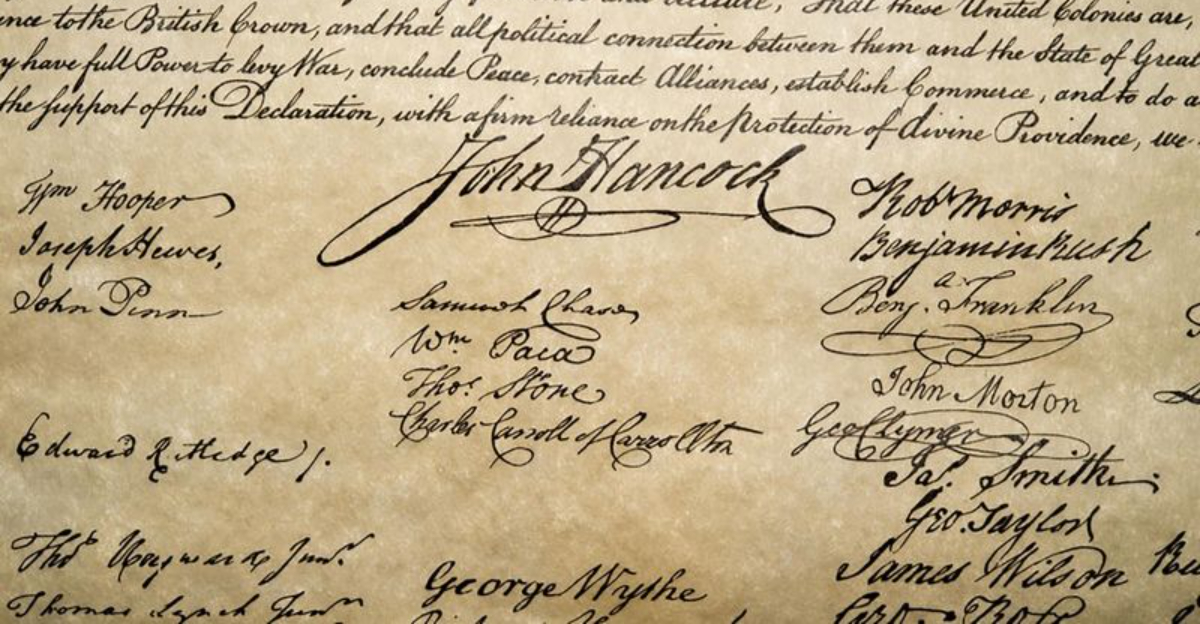

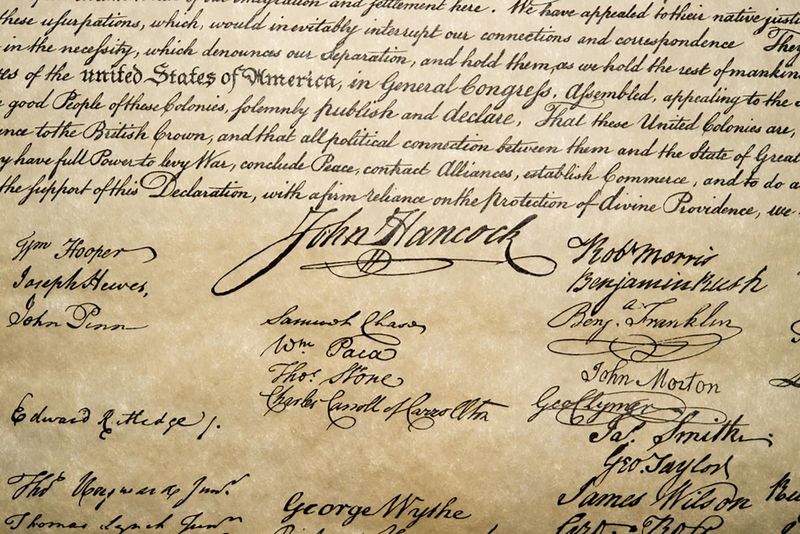

9. Hancock’s Signature Legend

John Hancock’s oversized signature spawned a famous myth. Supposedly, he signed extra-large so “King George could read it without his spectacles” – a defiant act of revolutionary bravado.

The truth is less dramatic but equally interesting. As President of the Continental Congress, Hancock signed first and alone on July 4th. His position entitled him to the center spot with ample space, while other signatures were added later in cramped conditions.

Hancock’s flamboyant handwriting wasn’t unusual for him – surviving documents show he always signed with similar flourish. Nevertheless, his name became synonymous with signatures, as in “put your John Hancock here.”

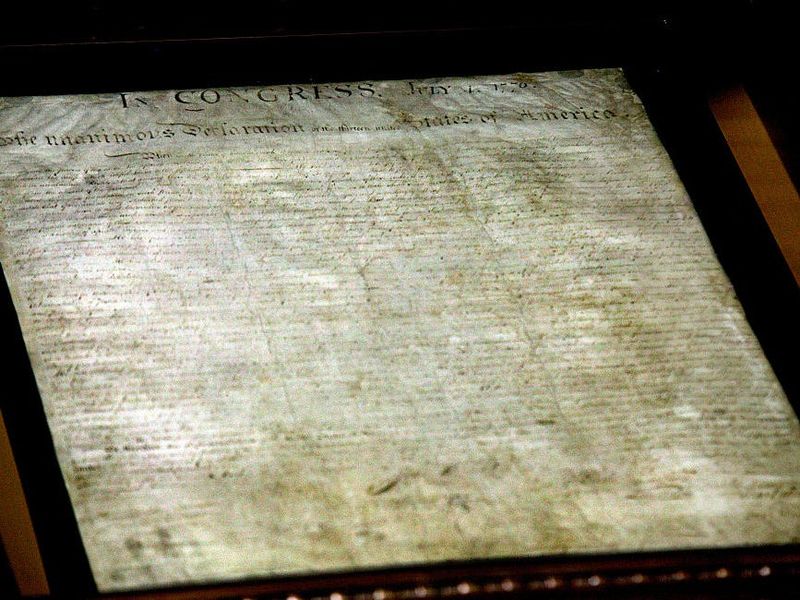

10. Preservation Nightmares

The Declaration nearly vanished twice due to preservation mistakes. During the 19th century, officials created an official copy using a wet-pressing technique that transferred some original ink to the press, severely fading the text.

Later, the document was displayed directly across from windows for over 30 years. Prolonged exposure to sunlight caused further deterioration, leaving the parchment yellowed and text barely visible today.

Modern conservators learned from these errors. Since 1952, the Declaration has been sealed in a titanium case filled with inert argon gas, displayed in a bulletproof enclosure at the National Archives, and lowered into a vault each night.

11. Rare Surviving Copies

Of hundreds of original Dunlap Broadsides printed on July 4-5, 1776, only 26 survive today. These first printed versions of the Declaration were distributed to colonial assemblies, committees, and commanding officers of the Continental Army.

Most were read aloud, posted publicly, then discarded or destroyed. Finding one today would be like winning the historical lottery – a Dunlap Broadside discovered in a flea market picture frame sold for $8.14 million in 2000!

Each surviving copy has its own fascinating journey. One was discovered in 1989 hidden behind a painting purchased at a Pennsylvania thrift store for $4, making it perhaps history’s most valuable accidental find.

12. Slow Rise to Reverence

Americans didn’t always revere the Declaration as they do today. For decades after 1776, it was considered primarily a wartime document – important historically but not sacred.

The shift began in the 1820s as the founding generation passed away. Political leaders like Abraham Lincoln later elevated the Declaration to almost religious status, focusing on its equality principles rather than its specific grievances against Britain.

By the Civil War, the document had transformed from practical political tool to national scripture. This evolution shows how Americans gradually constructed their national identity around the Declaration’s ideals rather than its original limited purpose.

13. Washington’s Absence

George Washington never signed the Declaration despite being the Revolution’s military leader. When the Continental Congress debated independence in Philadelphia, Washington was 90 miles away in New York, preparing to defend the city against imminent British attack.

Washington received his copy on July 9th and ordered it read to boost troop morale. Ironically, America’s most famous founding father missed the nation’s founding document signing.

Had the British naval attack succeeded in capturing Washington that summer, American independence might have collapsed before it began. His absence from the signing highlights how precarious the revolutionary cause was in those early months.

14. Wartime Road Trip

During World War II, the Declaration went on a secret journey to Fort Knox. In December 1941, just two weeks after Pearl Harbor, officials packed the document in a specially designed bronze container, cushioned it with cotton padding, and placed it in a reinforced case.

Under armed guard, the Declaration traveled by train to Kentucky alongside the Constitution and Bill of Rights. The precious cargo remained hidden in Fort Knox’s vault until 1944, when officials determined the threat of enemy attack had diminished.

This wartime precaution reflected both practical security concerns and the document’s growing symbolic importance to American identity during a global conflict.

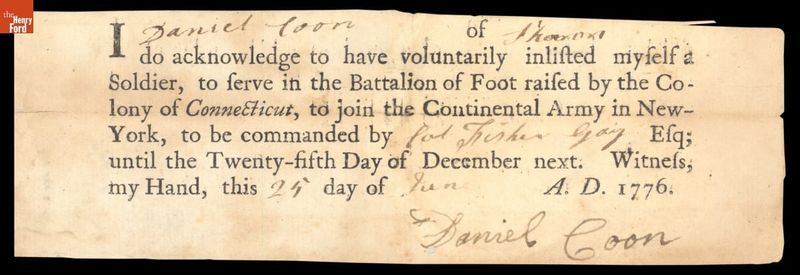

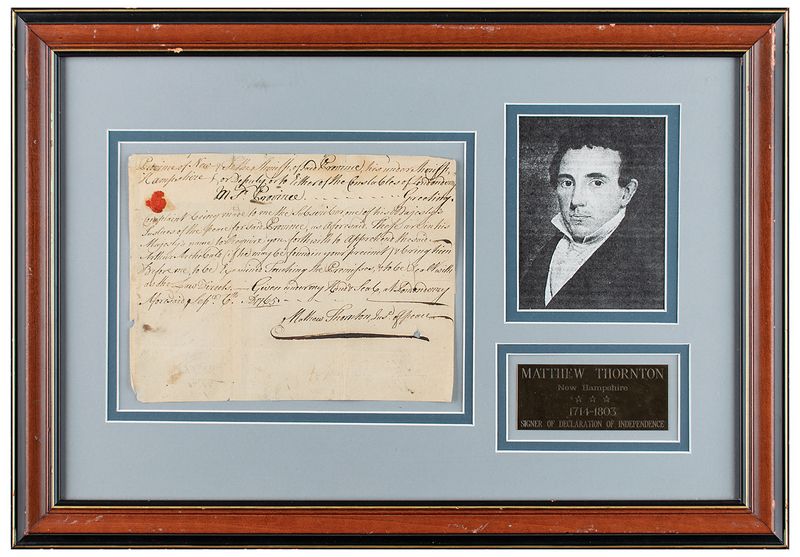

15. Late-Arriving Signer

Matthew Thornton of New Hampshire earned a peculiar distinction as the Declaration’s chronologically challenged signer. Elected to Congress in September 1776 – months after the document was approved – Thornton was nonetheless granted permission to add his name.

With no room left in the New Hampshire delegation’s section, Thornton’s signature appears awkwardly squeezed into available space at the bottom right. His late arrival demonstrates how fluid the signing process was.

Thornton wasn’t the only latecomer. Several delegates added their names weeks or months after July 4th, while others who voted for independence never signed at all due to illness, absence, or replacement by their state legislatures.