Long before mass production took over our lives, people created beautiful things with their own two hands. These handcrafted traditions weren’t just hobbies – they were essential skills passed down through generations, connecting families and communities. While modern technology has pushed many of these crafts to the brink of extinction, a growing movement of artisans is working to preserve these meaningful traditions before they vanish completely.

1. Quilting by Hand

Grandmother’s nimble fingers would stitch together fabric scraps, transforming yesterday’s dresses into tomorrow’s heirlooms. Every quilt told a story through its patterns – wedding ring designs for newlyweds or star motifs for a child’s birth.

Quilting bees brought women together in rural communities, combining practicality with socializing. Around a large wooden frame, they’d share gossip while their needles danced through layers of cotton batting.

Modern quilters typically use sewing machines, but traditional hand-quilting creates distinctive, tiny stitches impossible to replicate mechanically. The meditative rhythm of needle pulling thread through fabric connects today’s quilters with ancestors they never knew.

2. Canning and Preserving

Summer’s bounty once filled kitchens with steam and the sweet smell of fruit as families prepared for winter’s scarcity. Mason jars lined up like soldiers, waiting to be filled with jewel-toned jams, pickles, and vegetables. The distinctive ‘ping’ of a properly sealed jar was music to a homemaker’s ears.

Children would help by washing jars or picking berries, learning food preservation alongside multiplication tables. Before refrigeration became commonplace, this knowledge meant survival through harsh winters.

The science was precise – proper acidity, processing times, and headspace determined whether food would nourish or poison. Today’s canners often preserve family recipes alongside the technique itself.

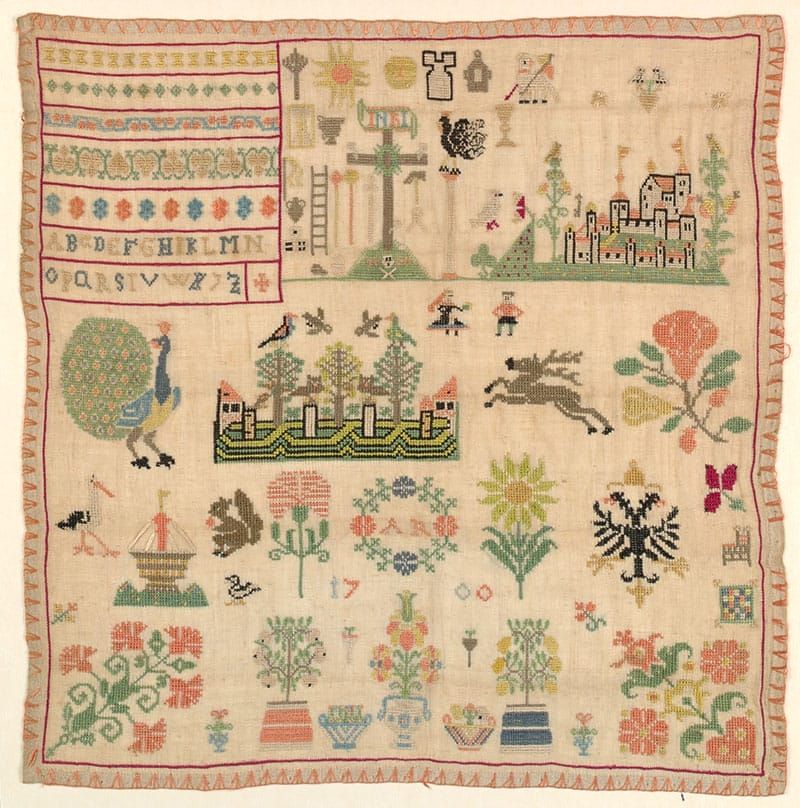

3. Embroidery

Colorful threads transformed plain linens into family treasures through the ancient art of embroidery. Young girls often learned their first stitches at age five or six, practicing on simple samplers that showcased their developing skills.

Each region developed signature styles – Hardanger from Norway with its geometric whitework or vibrant Mexican Otomi with its folkloric animals. American colonists adapted European techniques, creating distinctive styles that reflected their new homeland.

Beyond decoration, embroidery served as a quiet language. Hidden symbols in Ukrainian rushnyky conveyed messages about fertility and protection, while mourning samplers helped process grief. The therapeutic benefits of this slow, mindful craft are being rediscovered by a stressed-out modern generation.

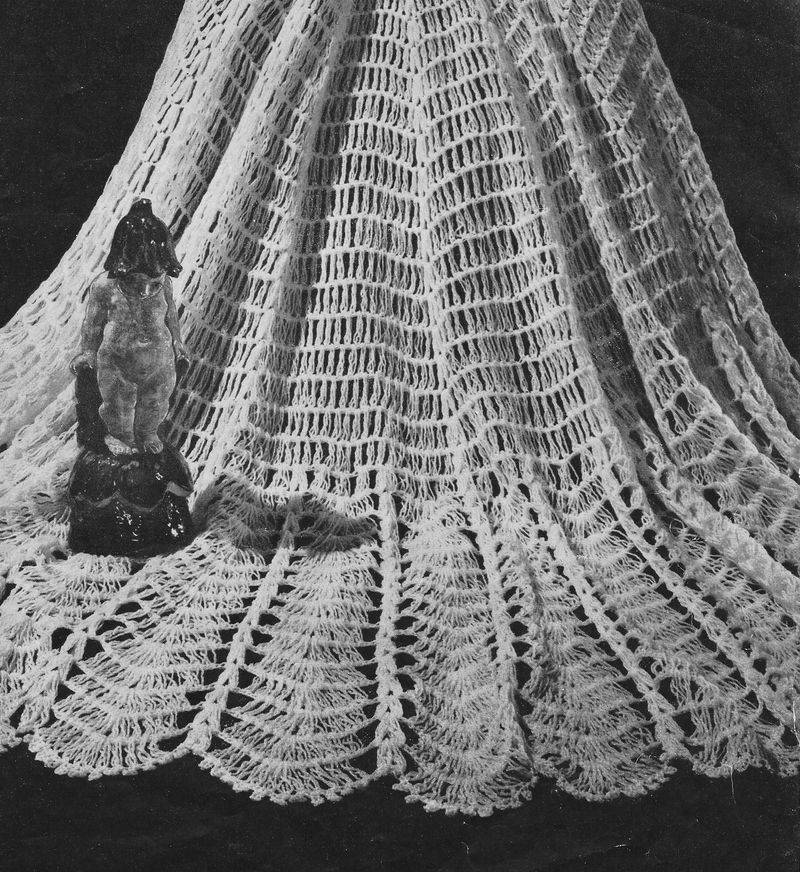

4. Tatting (Lace-Making)

Royal courts once prized the whisper-thin lace created through tatting – a technique involving small shuttles dancing between nimble fingers. Unlike knitting or crochet, tatted lace forms through a series of knots and loops, creating delicate patterns that adorned everything from christening gowns to wedding veils.

Tatting shuttles became family heirlooms, often crafted from ivory, tortoiseshell, or mother-of-pearl. The craft nearly disappeared in the 1950s when machine-made lace became affordable and fewer young women learned from their elders.

A tatted doily might represent hundreds of hours of work, with patterns memorized rather than written. Today, a small but dedicated community keeps this Victorian art alive through online tutorials and in-person workshops.

5. Basket Weaving

Harvested grasses, split oak, and willow branches became sturdy containers through the ancient craft of basket weaving. Native American tribes developed hundreds of distinct basket styles, each perfectly suited to specific purposes – from watertight cooking vessels to backpack-style carriers.

Appalachian communities relied on basket making for both utility and income. A skilled weaver could identify the perfect tree for harvesting splits by examining the bark, then transform raw materials into baskets that might outlive their makers.

Children often began with simple plaiting techniques before graduating to more complex patterns. The repetitive over-under motion created a meditative state, with knowledge passed through demonstration rather than written instructions. Modern basket weavers often struggle to source traditional materials due to habitat loss.

6. Candle Making

The autumn ritual of candle making once signaled winter’s approach. Families would gather around bubbling pots of tallow or beeswax, dipping wicks repeatedly until candles reached proper thickness. The sweet honey scent of beeswax or the earthy smell of bayberry filled homes during this essential task.

Colonial households might need 200-300 candles to survive winter’s darkness. Children participated by preparing wicks or helping with simpler dipped tapers while adults created molded candles for special occasions.

Before electricity, these handmade lights represented both necessity and luxury. Wealthy homes used beeswax or bayberry candles with cleaner, brighter flames, while poorer families relied on smoky tallow candles made from animal fat. Modern candle making focuses on aesthetics rather than survival.

7. Soap Making

Frontier families transformed waste into necessity through the dangerous alchemy of soap making. Wood ash lye combined with rendered animal fat in large iron kettles, creating a caustic mixture that required careful handling. The process took days – from collecting hardwood ash to leaching lye, rendering fat, and boiling the mixture to the perfect consistency.

Spring was soap-making season, when winter’s accumulated ashes and butchering fat could be processed outdoors. Children learned to respect the potent lye that could burn skin but also transform greasy dishes and dirty clothes.

Herbs or flower petals might be added for fragrance or medicinal properties. Modern artisanal soap makers have revived this craft with safer ingredients and scientific precision, though few use traditional lye made from wood ash.

8. Rug Hooking

Born from necessity in 19th century New England, rug hooking transformed fabric scraps into warm floor coverings for drafty homes. Using simple tools – a metal hook and burlap backing – women pulled loops of wool through the coarse backing to create durable, washable rugs.

Unlike elite needlework, rug hooking was considered a “country craft” practiced by rural and working-class women. Designs ranged from practical geometrics to elaborate pictorials depicting farm scenes or family homes.

Wool from outgrown clothing was carefully cut into strips, with dark colors reserved for borders and backgrounds. The craft nearly vanished during the Depression when manufactured flooring became affordable, but was revived in the 1960s as an art form rather than a necessity.

9. Knitting and Crocheting

Clicking needles and flying hooks once formed the soundtrack of evening family gatherings. While the television remained silent, stories flowed alongside the growing fabric of sweaters, socks, and blankets. Both practical and portable, these yarn crafts traveled from front porches to factory lunch breaks.

During World Wars I and II, knitting became patriotic duty as civilians created socks and sweaters for soldiers. Children learned simple stitches in school, with rhymes helping them remember complex patterns: “In through the front door, around the back, peek through the window, and off jumps Jack.”

Unlike many traditional crafts, knitting and crocheting never completely disappeared, though they transformed from necessity to hobby. Modern practitioners often learn from videos rather than family members, creating connections across digital rather than physical space.

10. Whittling

Pocket knives transformed ordinary sticks into extraordinary objects through the contemplative craft of whittling. Unlike formal woodcarving with its specialized tools, whittling required only a sharp blade and patience. Farm boys might carve simple toys during quiet moments watching livestock, while older men created practical items like butter paddles or fishing lures.

The craft served as both entertainment and informal apprenticeship. Through whittling, young hands learned how different woods behaved – pine’s softness versus oak’s stubborn grain – while developing knife control and design thinking.

Whittling circles formed around courthouse squares and country stores, where men exchanged stories alongside carving techniques. The distinctive spiral of wood shavings at someone’s feet signaled membership in this informal brotherhood, now rarely seen outside dedicated craft schools.

11. Leatherworking

The rich aroma of tanned hides once filled workshops where leather was transformed into everything from harnesses to fine boots. Leatherworking combined utility with artistry – practical items made beautiful through tooling, stamping, and dyeing techniques passed through generations.

Frontier families often practiced basic leatherwork out of necessity. Children might start with simple projects like knife sheaths before advancing to more complex items. The craft required specialized tools: awls for stitching holes, bevelers for decorative edges, and swivel knives for detailed carving.

Native American tribes developed distinctive styles using brain-tanning methods and porcupine quill embellishments. While commercial production has largely replaced handcrafted leather goods, a renaissance has emerged among craftspeople seeking connection to this tactile tradition with its distinctive smell and feel.

12. Weaving

The rhythmic clack of the loom once formed the heartbeat of American homes, transforming raw fiber into cloth for everyday use. Families might dedicate an entire room to a floor loom where wool, cotton, or flax became fabric through the careful interlacing of threads.

Weaving represented independence during colonial times. Many households maintained sheep specifically for home textile production, processing wool from shearing through spinning and weaving.

Pattern drafts became family treasures, passed down alongside weaving skills. Distinctive regional styles emerged – colorful coverlets from Pennsylvania or sturdy rag rugs from New England. While industrialization nearly extinguished home weaving by 1900, fiber artists and living history museums have preserved these techniques, celebrating the mathematical precision and creative expression found in this ancient craft.

13. Stenciling and Folk Painting

Before wallpaper became affordable, American homes gained color and pattern through hand-stenciled walls and furniture. Itinerant painters traveled from town to town with collections of hand-cut stencils, transforming plain surfaces with borders of pineapples, eagles, or flowering vines.

Folk painting traditions varied by region and cultural background. Pennsylvania German settlers created colorful hex signs for barns, while New England painters developed distinctive theorem painting on velvet. These decorative techniques required simple materials – homemade paints, brushes from animal hair, and stencils cut from oiled paper.

Children often learned by helping mix pigments from berries, roots, or minerals. When manufactured goods became widely available in the late 19th century, these personalized decorative traditions faded, though they’ve been revived by historical societies and decorative artists preserving regional aesthetics.

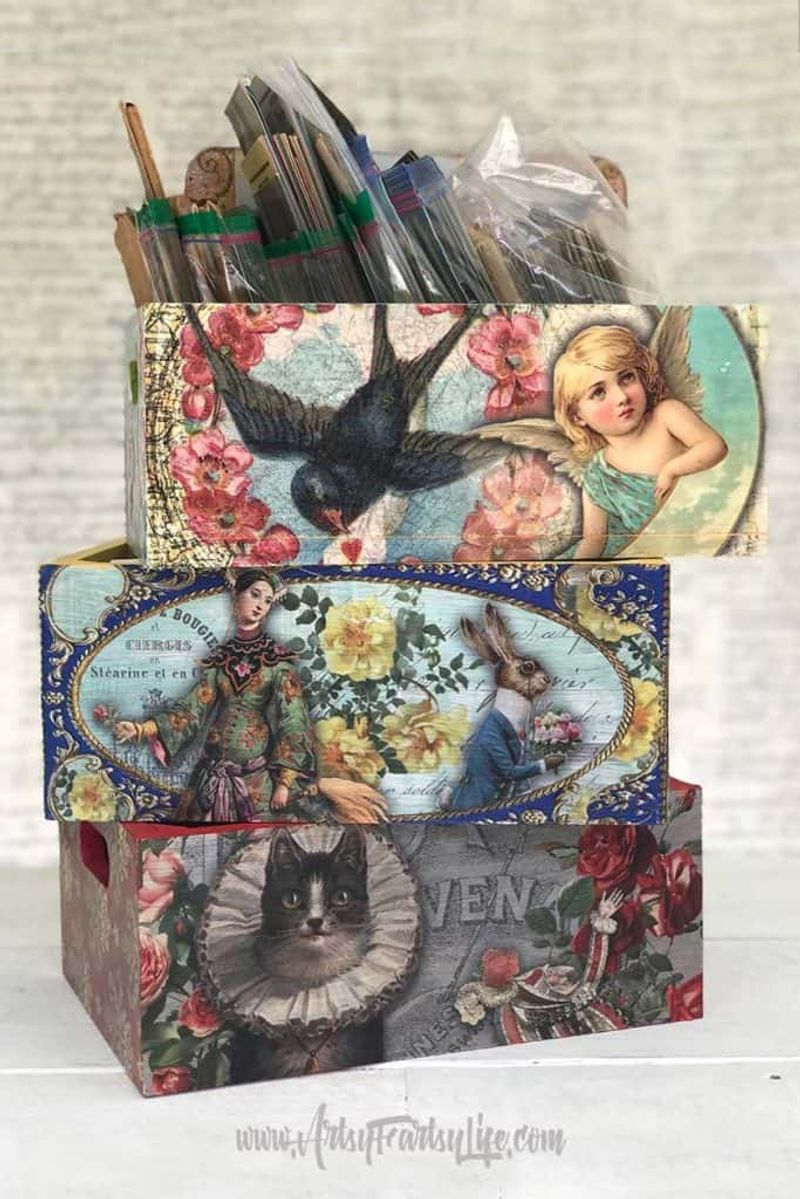

14. Decoupage

Magazine clippings, decorative papers, and layers of varnish transformed ordinary objects into conversation pieces through the Victorian art of decoupage. Queen Victoria herself embraced this accessible craft, helping popularize it among middle-class women seeking affordable ways to beautify their homes.

Practitioners carefully cut printed images – flowers, birds, or classical figures – then arranged them on surfaces ranging from small boxes to entire folding screens. Each layer received multiple coats of varnish, creating a finish that appeared painted rather than pasted.

The craft experienced several revivals, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s when mod podge simplified the process. Unlike many traditional crafts requiring years of practice, decoupage offered beginners immediate satisfaction. While no longer mainstream, this paper craft continues through altered books and mixed media art, preserving its accessible creative spirit.

15. Sewing Clothes by Hand

From first light until candles guttered, women’s hands once moved steadily through the essential task of clothing their families. Every stitch represented both necessity and care – hemming baby’s first gown or piecing father’s work shirt from fabric woven on the family loom.

Young girls began their sewing education by age six, creating samplers that taught both stitches and moral virtues. By their teens, many could construct entire garments without patterns, using body measurements and fabric scraps with remarkable efficiency.

Hand-sewing gatherings combined productivity with community building. Women might travel miles to participate in sewing circles that provided social connection while completing tedious work. While machines eventually replaced most hand-sewing, the intimate knowledge of fabric and construction techniques has experienced revival through sustainable fashion movements.