Remember when product packaging could say just about anything to get you to buy? Before consumer protection laws, companies played fast and loose with the truth on their labels. From cigarettes claiming doctor approval to candy containing actual drugs, these vintage packages weren’t just stretching the truth – they were snapping it in half. Looking back at these marketing tactics feels like visiting a bizarre alternate universe where companies could make outrageous claims without consequences.

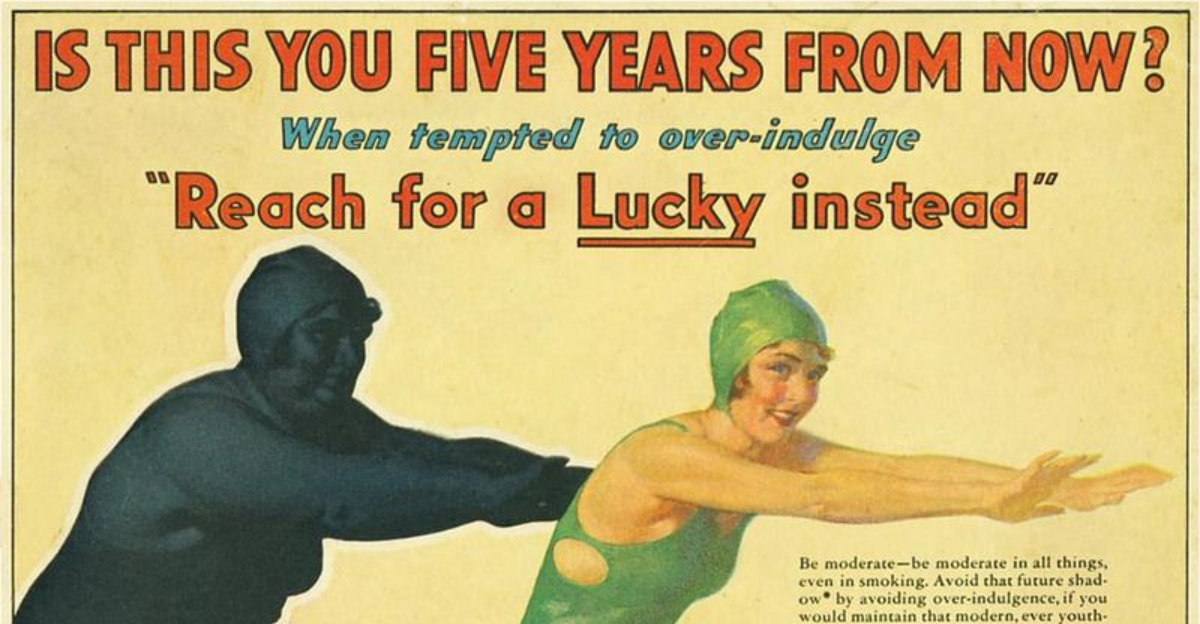

1. Lucky Strike’s Doctor-Endorsed Cigarettes

The tobacco industry once wielded medical authority like a magic wand. Lucky Strike boldly plastered “Recommended by Doctors” across their cigarette packs in the 1930s and 40s, complete with actors in white coats giving approving nods. The company paid physicians to endorse their product, claiming it was “less irritating to the throat” than competing brands. Some advertisements even suggested smoking as a weight-loss method! Modern FDA regulations now strictly prohibit any health claims for tobacco products. The manipulation of medical credibility to sell deadly products represents one of advertising’s darkest chapters – a practice that helped delay public recognition of smoking’s dangers for decades.

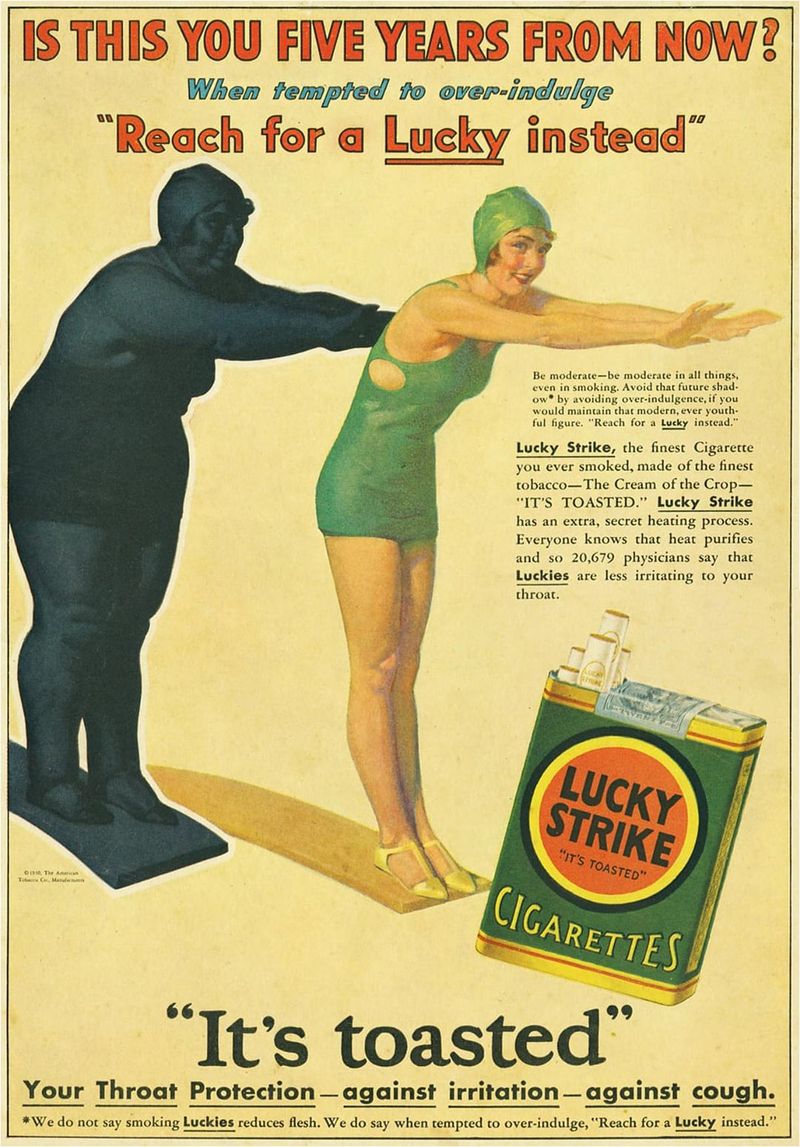

2. Cocaine Toothache Drops for Children

Parents in the late 1800s unknowingly dosed their crying infants with actual cocaine. These innocent-looking drops, marketed by Lloyd Manufacturing, promised “instantaneous cure” for teething pain and dental aches. The cheerful packaging featured smiling children, while the 15-cent medicine contained cocaine hydrochloride without any dosage warnings or safety instructions. Sold over-the-counter at general stores, these drops were just one of many cocaine-laced products before the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act. Today, such a product would violate dozens of laws and regulations. The casual distribution of unregulated narcotics to children represents a shocking reminder of how far consumer protections have evolved.

3. Sugar-Free Candy’s Explosive Secret

The “sugar-free” revolution of the 1970s and 80s created a minefield of digestive disasters. Candy packages proudly proclaimed “NO SUGAR!” in bold letters, but failed to mention the laxative effects of their sugar alcohol substitutes. Brands like BreathSavers and Sugar-Free Gummy Bears contained massive amounts of sorbitol and maltitol. Consumers who ate these treats in normal quantities often experienced severe intestinal distress – a fact conveniently missing from the cheerful packaging. Modern FDA regulations now require warning labels about potential digestive effects when products contain certain sugar alcohols. The misleading health halo of these early sugar-free products shows how selective disclosure can be just as deceptive as outright lying.

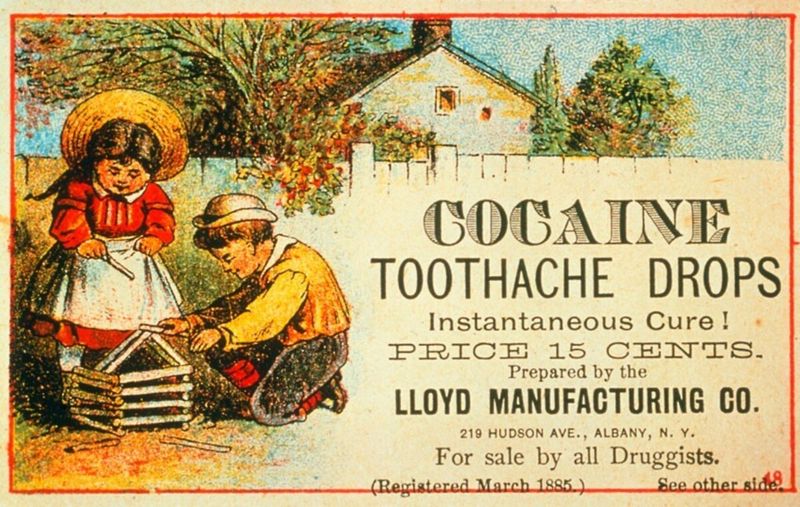

4. Fleischmann’s Trans-Fat Loaded “Heart-Healthy” Margarine

Margarine’s reputation as a heart-healthy alternative to butter represents one of food marketing’s greatest deceptions. Fleischmann’s margarine packages in the 1960s and 70s proudly declared “Cholesterol-Free!” with heart symbols and health claims. What consumers didn’t know: these products contained dangerous trans fats that significantly increased heart disease risk. The bright yellow tubs featured images of happy families and suggested doctor approval, despite mounting evidence of harm. Current FDA regulations require trans fat disclosure and have effectively banned partially hydrogenated oils. This case demonstrates how selective truth-telling – highlighting the absence of one harmful ingredient while hiding another – can mislead consumers about a product’s overall health impact.

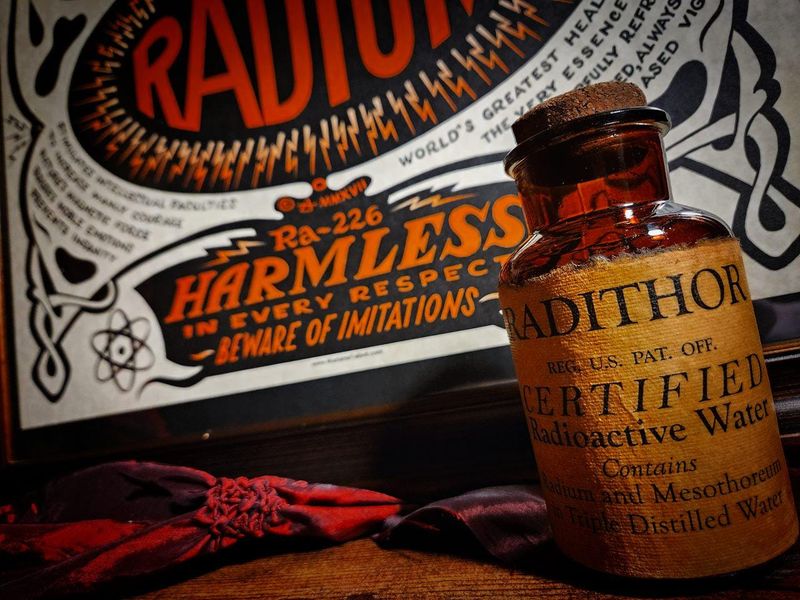

5. Radithor: The Radioactive Energy Drink

Glowing health took on a literal meaning with Radithor, a 1920s tonic that proudly advertised itself as “Certified Radioactive Water.” The elegant bottles contained distilled water infused with radium – a substance we now know causes radiation poisoning and cancer. Marketed as an energy booster and virility enhancer, Radithor’s packaging featured scientific-looking certificates and high-society endorsements. The product gained notoriety when industrialist Eben Byers died after consuming 1,400 bottles, his jaw and bones disintegrating from radiation. This catastrophic product directly influenced the creation of the FDA. Modern regulations prohibit radioactive substances in consumer products – a reminder that scientific-sounding claims can mask deadly dangers.

6. Baby Beauty Soap’s Skin-Whitening Promises

Pink packaging adorned with cherubic babies concealed troubling messages in mid-century skin-whitening soaps. Products like Nadinola and Fair & Lovely promised “whiter skin guaranteed” to mothers concerned about their children’s social prospects. These soaps, marketed across Asia, Africa, and America, contained mercury compounds and hydroquinone – substances now known to cause organ damage and skin disorders. Advertisements suggested lighter skin determined a child’s future success and marriageability. Today, such marketing would violate anti-discrimination standards and FDA safety regulations. The exploitative nature of these products – preying on social prejudices while delivering toxic ingredients – represents a particularly harmful intersection of cultural manipulation and consumer deception.

7. Campbell’s Ingredient Sleight-of-Hand

Campbell’s soup cans from the 1960s featured appetizing images of chicken chunks and vegetables swimming in savory broth. Reality often told a different story – watery concoctions with sparse meat pieces barely visible under a sea of salt and additives. Before modern ingredient labeling laws, Campbell’s and other soup manufacturers weren’t required to list ingredients in descending order of quantity. A soup might picture juicy meat but contain mostly water, salt, and MSG, with actual chicken appearing fifth or sixth on the ingredient list. Current FDA regulations mandate honest ingredient ordering and nutritional information. This historical packaging deception demonstrates how visual promises on packages created expectations that the actual products couldn’t deliver – a practice now constrained by truth-in-advertising laws.

8. Candy Cigarettes: Training Wheels for Addiction

Chalk-white sticks wrapped in perfect replicas of Marlboro and Lucky Strike packaging introduced millions of children to smoking imagery. Candy cigarettes of the 1950s-70s even featured red tips that mimicked lit cigarettes and produced puffs of powdered sugar “smoke.” Manufacturers marketed these treats directly to children with cartoon characters and placement near actual candy. The packaging made no distinction between the real product and the candy version, creating brand familiarity years before legal smoking age. Many countries now ban or restrict candy cigarettes due to their role in normalizing tobacco use. This deliberate blurring of adult and children’s products represents a particularly cynical marketing strategy that exploited children to develop future cigarette consumers.

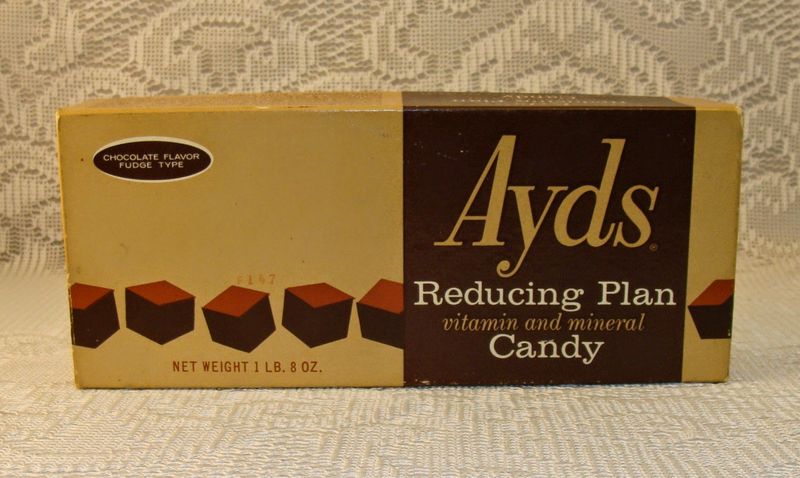

9. Ayds Weight Loss Candy’s Unfortunate Promise

The chocolate-caramel squares in Ayds’ weight loss candy boxes contained a secret ingredient: benzocaine, a numbing agent that deadened taste buds. The packaging promised users would “eat less, lose weight” through appetite suppression – without mentioning the pharmaceutical nature of its mechanism. Marketed primarily to women in the 1970s and early 80s, Ayds (pronounced like “aids”) featured before-and-after photos and claims of clinical effectiveness without substantial evidence. The unfortunate name became its downfall when the AIDS health crisis emerged. Modern regulations would require pharmaceutical disclosure and prohibit unsubstantiated weight loss claims. This product represents the blurry historical line between candy, medicine, and cosmetics that consumer protection laws now clearly define.

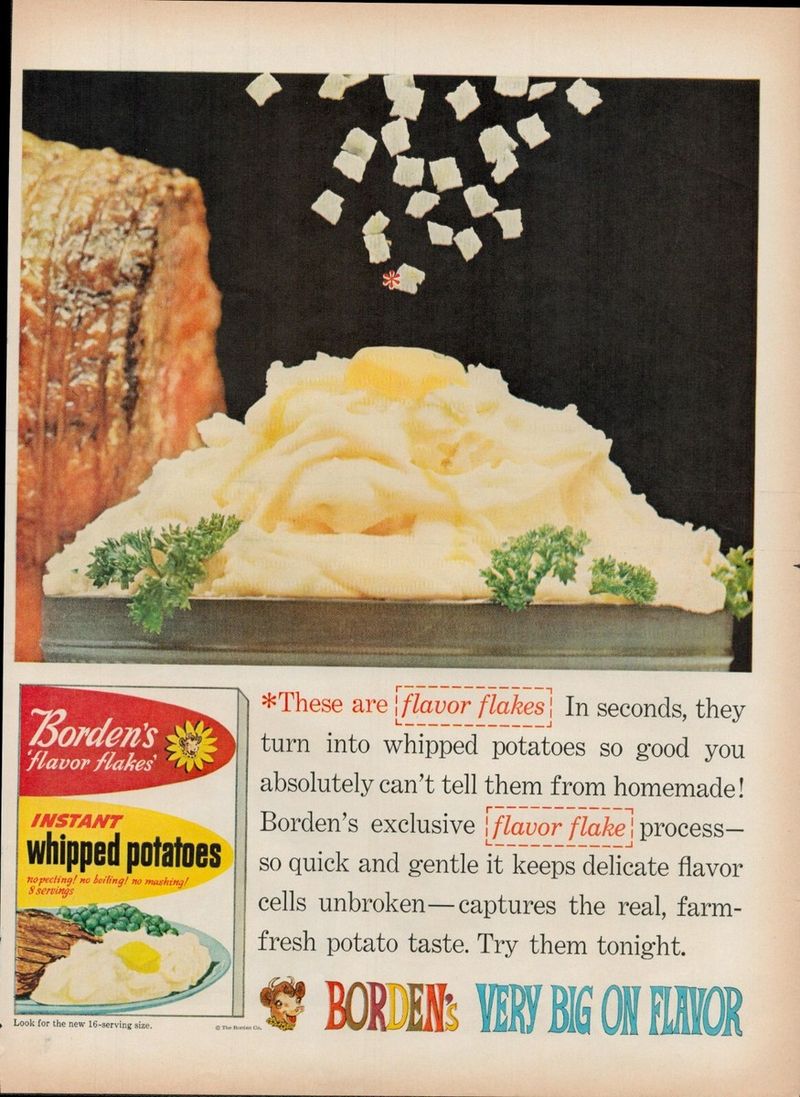

10. Instant Mashed Potatoes’ Farm-Fresh Illusion

Boxes of instant mashed potatoes from the 1960s featured farmhouses, fresh potatoes, and happy families enjoying what appeared to be homemade side dishes. Brands like Betty Crocker and Hungry Jack prominently claimed “Made with Real Potatoes!” in bold lettering. The reality inside those boxes? Highly processed potato flakes with preservatives, artificial flavors, and sodium compounds that bore little resemblance to actual potatoes. Manufacturers conveniently omitted mentioning the industrial dehydration process and chemical additives. Current regulations require clearer qualification of such claims. This disconnect between packaging imagery and actual contents demonstrates how nostalgic farm imagery created a halo effect around heavily processed foods – a practice that continues in more subtle forms today.

11. Jell-O’s Complete Meal Deception

Vibrant Jell-O packages from the 1930s-50s marketed gelatin desserts as appropriate meal replacements, particularly for weight-conscious women. Advertisements showed housewives serving colorful Jell-O molds as dinner centerpieces, with packaging that emphasized “satisfying” and “wholesome” qualities. Nutritionally, these products offered little beyond sugar, artificial colors, and gelatin. Some varieties suspended vegetables or fruits in the gelatin to enhance the illusion of nutritional value, while the packaging suggested regular meal substitution. Modern nutritional labeling requirements would prevent such implied meal-replacement claims. This marketing approach exploited women’s body image concerns while promoting potentially harmful eating patterns – demonstrating how packaging can normalize problematic consumption behaviors.

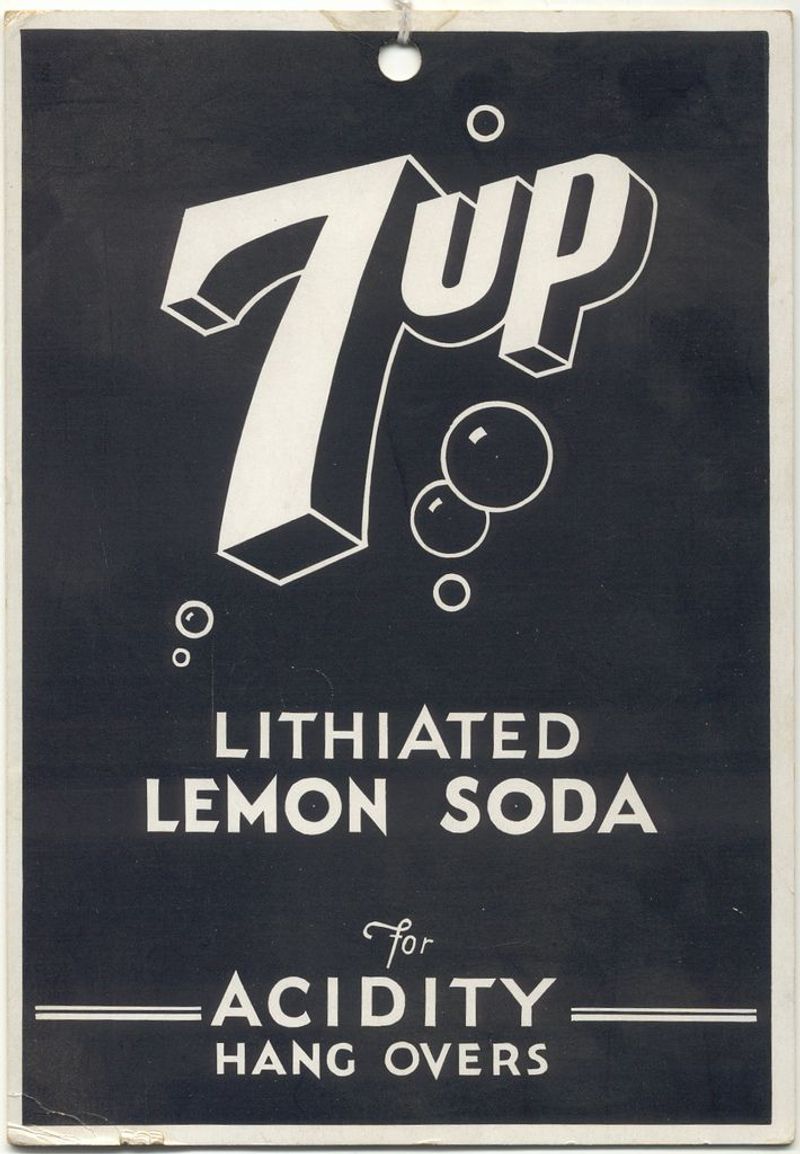

12. 7-Up’s Secret Mood-Altering Ingredient

Those crisp, clean 7-Up bottles from the 1930s and 40s hid a surprising secret ingredient: lithium citrate, a powerful mood-stabilizing drug now prescribed for bipolar disorder. The refreshing green bottles promised “mood elevation” and claimed to cure hangovers and even depression. 7-Up marketed itself as a health tonic rather than a soft drink, with packaging that emphasized its “medicinal” properties. The lithium remained in the formula until 1948, though the health claims persisted well into the 1950s. Current FDA regulations prohibit adding pharmaceuticals to food products without disclosure. This bizarre chapter in soft drink history reveals how commonly consumable products once contained powerful drugs without consumer knowledge – a practice now strictly regulated.

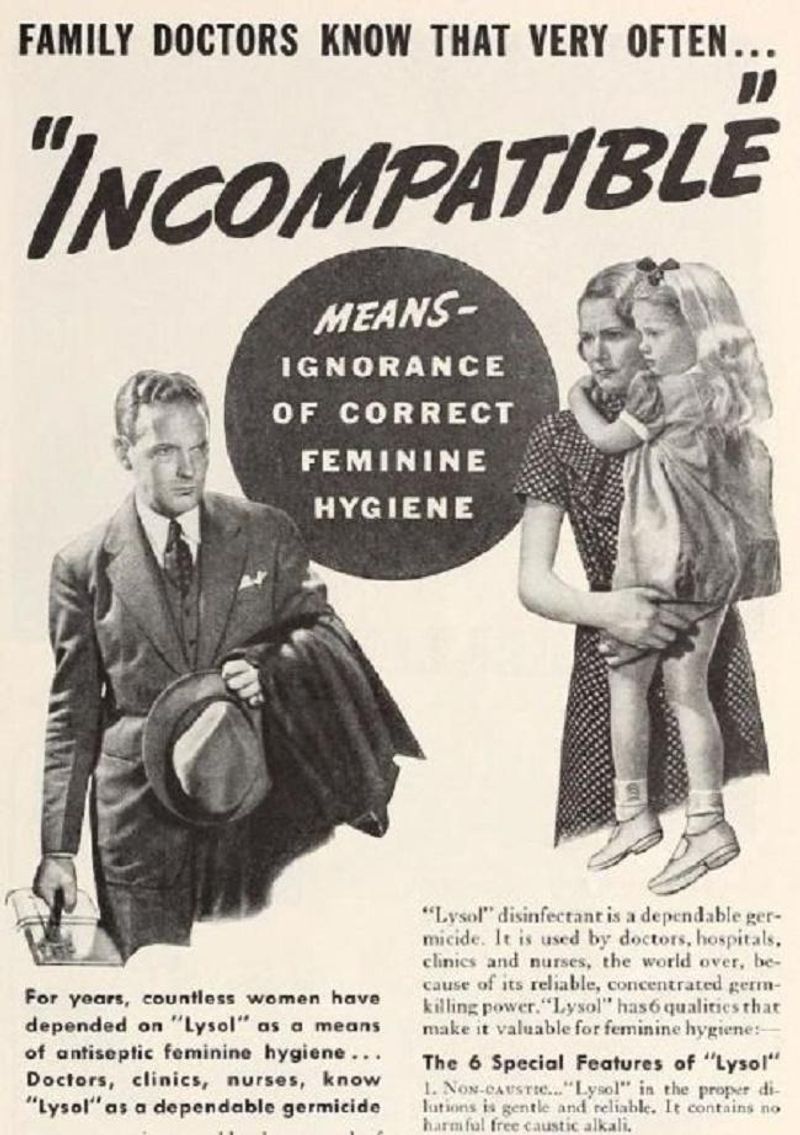

13. Lysol’s Disturbing ‘Feminine Hygiene’ Marketing

Brown glass bottles of Lysol disinfectant from the 1930s-50s featured demure packaging with coded language about “feminine hygiene” and “marital happiness.” Women recognized these as veiled references to contraception and vaginal cleansing. Lysol’s packaging suggested regular intimate use of this harsh chemical disinfectant, causing chemical burns, inflammation, and even death in some cases. The bottles featured romantic imagery of couples and subtle suggestions that wives who used Lysol remained desirable to their husbands. Modern regulations prohibit both misleading medical claims and dangerous off-label uses. This particularly harmful marketing exploitation took advantage of women’s limited access to contraception and medical information, causing physical harm while playing on relationship insecurities.

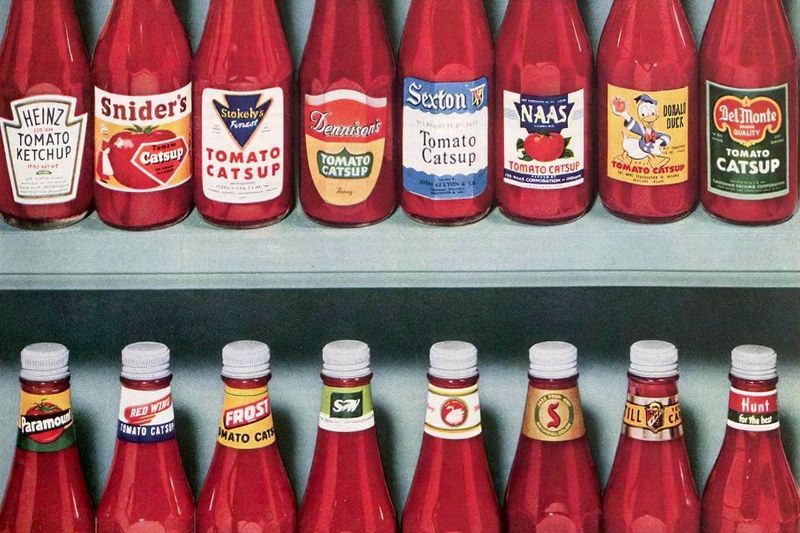

14. Ketchup’s ‘All Natural’ Color Trick

Ketchup bottles from the 1970s proudly proclaimed “No Artificial Colors!” in bold lettering while glossing over the cocktail of other artificial ingredients inside. Brands like Heinz and Hunt’s featured farm-fresh tomatoes on labels, creating a natural halo effect. Meanwhile, these products contained newly-developed high fructose corn syrup, artificial preservatives, and flavor enhancers. The selective emphasis on one natural aspect while hiding numerous artificial components exemplifies the “health washing” that dominated food marketing before comprehensive labeling laws. Today’s clean labeling regulations require more complete disclosure of ingredients. This historical packaging strategy – highlighting a single positive attribute to mask multiple negative ones – continues to evolve as consumers become more ingredient-conscious.

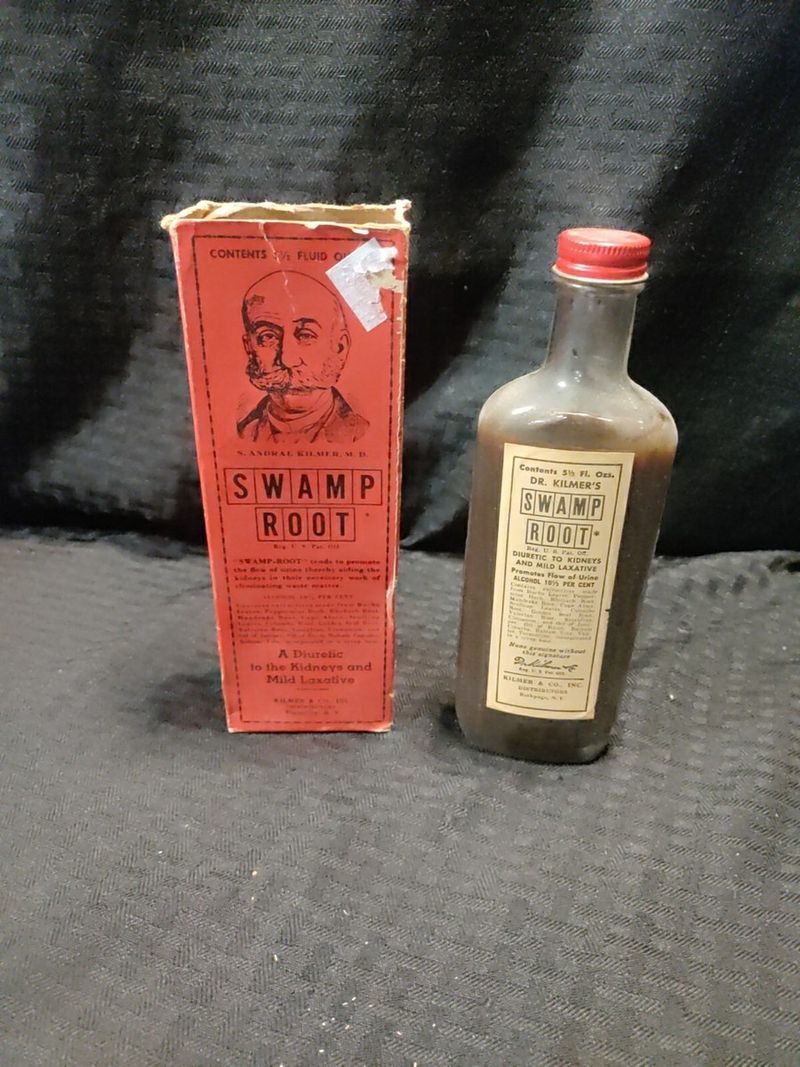

15. Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root Kidney Cure-All

Ornate bottles of Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root promised miraculous healing for virtually every ailment known to humankind. The elaborate packaging featured pseudo-scientific language, testimonials from “cured” patients, and claims of effectiveness against kidney disease, liver problems, and even “female complaints.” Inside the impressive bottle? A simple mixture of alcohol, water, and plant extracts with no proven medical benefits. These products remained on shelves well into the 1970s in some rural areas, despite containing up to 12% alcohol with no therapeutic value. Modern FDA regulations prohibit unsubstantiated health claims and require clinical evidence. This quintessential snake oil represents the wild west era of patent medicines that directly led to the creation of consumer protection agencies.