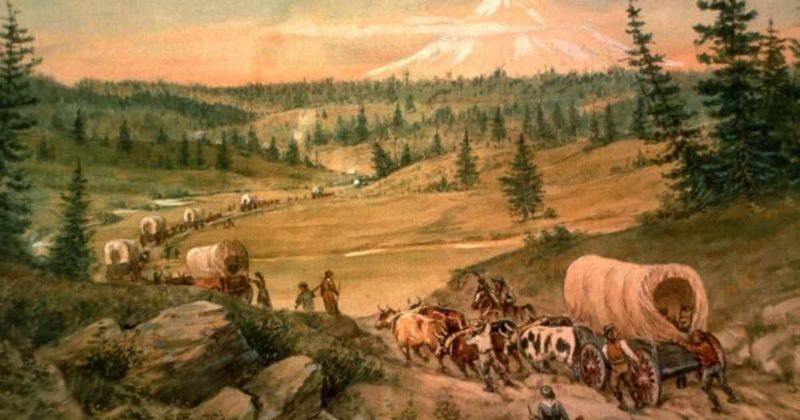

Traveling by covered wagon in the Old West was a journey characterized by endurance, resourcefulness, and a constant battle with the elements. These travelers embarked on a long and arduous trek, driven by dreams of new beginnings and opportunities in the vast, untamed territories. From the design of the “prairie schooners” to the social dynamics within wagon trains, each aspect of this journey required careful planning and adaptation. This guide explores the 15 essential aspects that defined this iconic chapter of American history, shedding light on the adventures and challenges faced by those who braved the trails.

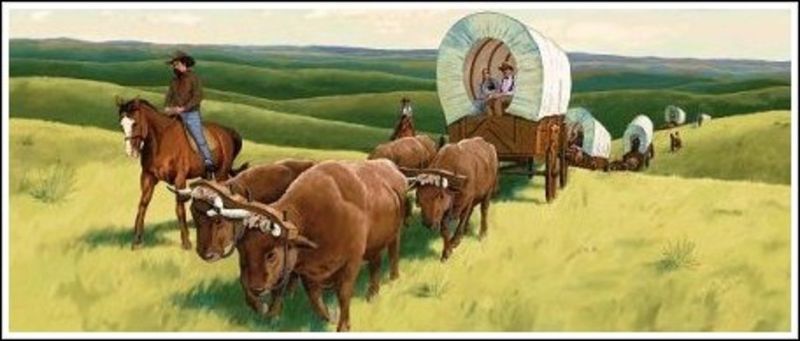

1. Slow and Steady: Average Pace of 10–15 Miles a Day

At a mere 2–3 miles per hour, covered wagons trudged along, barely overtaking a leisurely walk. Pioneers calculated daily journeys of 10–15 miles, mindful of the need to rest their animals.

The pace allowed for essential activities like setting up camps and hunting. It wasn’t a sprint; it was a marathon. Time was taken to forage and sometimes hunt for sustenance.

This pace required patience and perseverance as each mile was hard-earned. The trail’s slow rhythm shaped the pioneers’ mindset, as days stretched into weeks on the open plains.

2. The “Prairie Schooner” Design

Dubbed “prairie schooners” for their billowing canvas tops, these wagons were the ships of the plains. Lightweight and nimble, they were designed to brave the harsh landscapes.

The slender wheels reduced friction on the dusty trails, enhancing maneuverability. The wagon’s structure was both a home and a fortress, its design crucial for survival.

While their aesthetics seemed simple, these wagons were ingeniously crafted to withstand sudden rainstorms and the relentless sun. Their enduring design marked them as quintessential symbols of westward expansion.

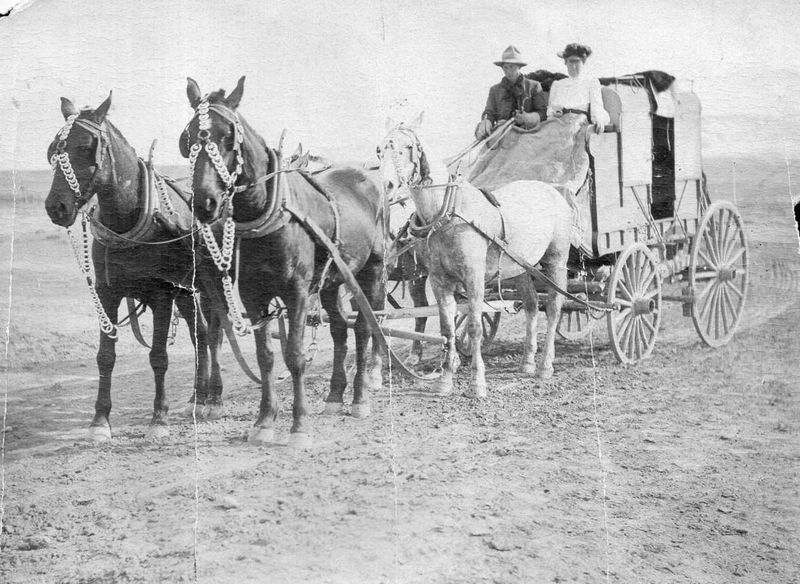

3. Oxen vs. Mules vs. Horses

Choosing the right animal was as strategic as packing supplies. Oxen were favored for their strength and resilience, thriving on sparse prairie grasses.

Mules offered endurance and sure-footedness through rough terrains, while horses, though faster, were temperamental and required more food. Each choice had its own trade-offs.

The bond between animal and driver was vital. Decisions often boiled down to personal preference or the specific demands of the terrain ahead. Each animal added a unique dynamic to the journey.

4. Packing Essentials: One Cubic Foot per Person

Packing for the trail meant ruthless decisions. Each person was allotted a mere cubic foot for personal items.

Prioritizing was crucial; cooking pots, spare clothing, and tools took precedence. Sentimental items were a luxury few could afford. The Bible often earned a spot as a spiritual anchor.

Overloading risked disaster, as excess weight could cripple the wagon. Thus, emigrants had to balance practicality with sentiments, a task that defined the essence of their journey.

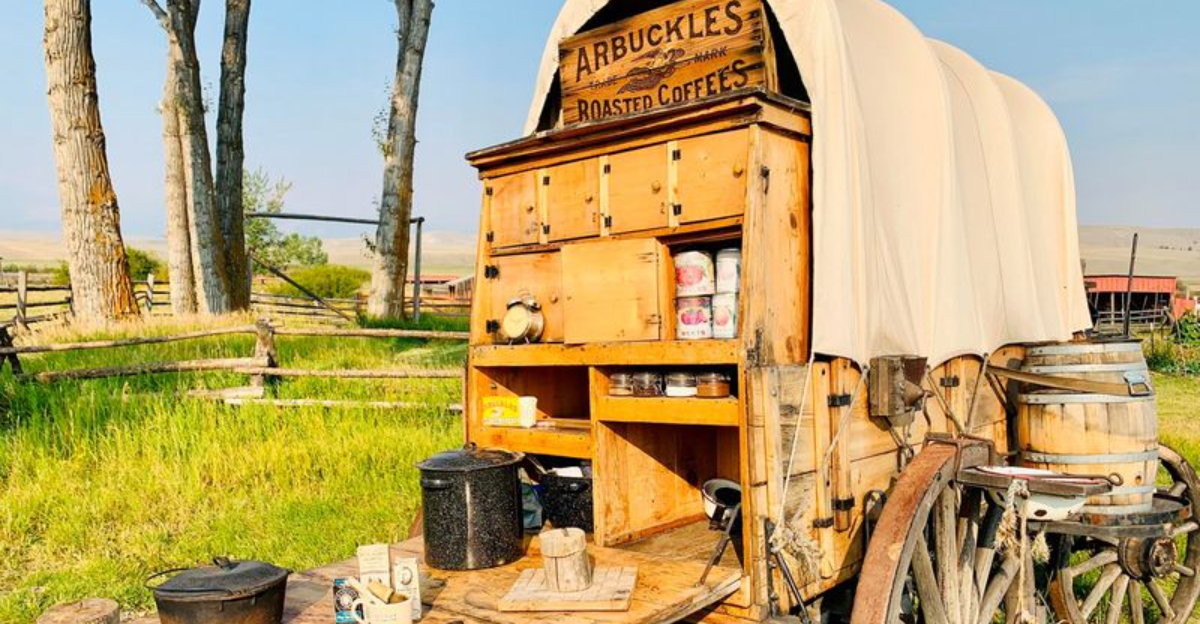

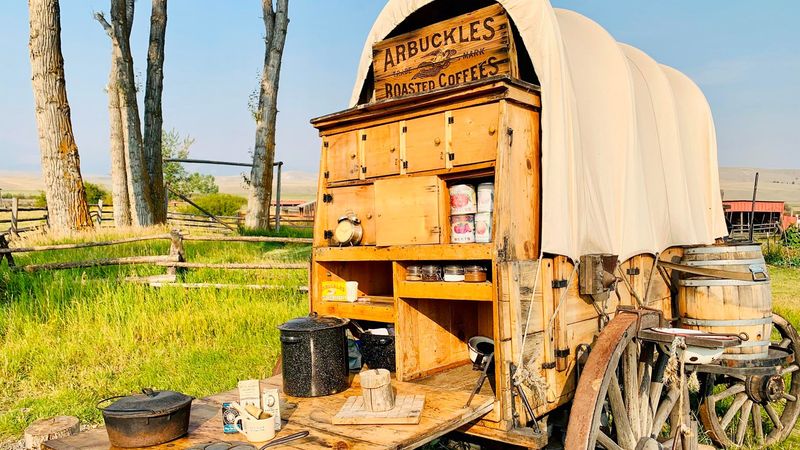

5. The Wagon Box: Your Mobile Home

A family’s sanctuary, the wagon box was more than a storage space—it was a mobile home.

Inside its 4- to 6-foot depth, barrels of food, cooking gear, and spare parts were meticulously arranged. At night, the tailgate became a communal hub, a makeshift table for weary travelers.

This compact space fostered innovation and adaptability, turning every inch into functional living quarters. The wagon box was a microcosm of frontier life, where resources were limited, and ingenuity thrived.

6. Trail Rations: Hardtack, Bacon, and Beans

Meals on the trail were a testament to survival instincts. Hardtack, a rock-hard biscuit, was a staple. Salted pork or bacon provided protein, while beans added sustenance.

Fresh meat was a luxury pursued through hunting, though overhunting soon made game scarce. Coffee and sugar offered brief moments of indulgence.

These rations fueled the arduous days but also reflected the scarcity and sacrifice inherent in the journey. The simple ingredients became symbols of resilience and tenacity.

7. The Importance of Water Sources

Water was life on the trail. Wagon trains followed rivers, creeks, and springs like lifelines, mapping daily water stops meticulously.

Oxen and humans alike could drink up to 15 gallons each per day. Missing a waterhole often spelled disaster, turning the quest for water into a race against time.

The need for water dictated routes and schedules, underscoring its critical role in survival. It was a constant reminder of the harsh realities on the trail, shaping every decision.

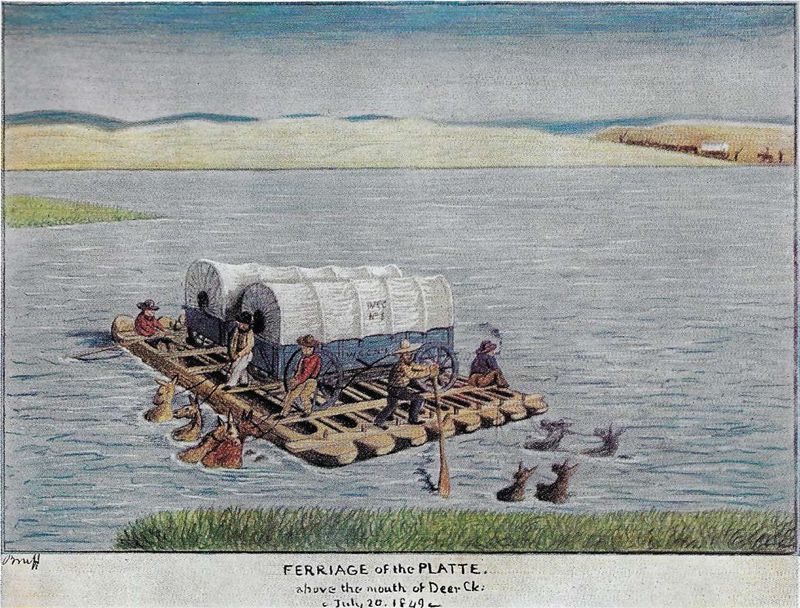

8. Crossing Rivers: Caulking and Ferry Fees

Rivers presented formidable challenges, requiring ingenuity and patience. Some wagons were caulked to float across, while others waited for ferries, paying fees of $1–$3 per wagon.

High waters could delay crossings for weeks, testing endurance and resources. The risk of losing goods or lives was always present.

These crossings were pivotal moments, demanding collaboration and strategic planning. They encapsulated the spirit of pioneering—overcoming obstacles with determination and teamwork.

9. Hand-Digging for Wagon Wheel Repairs

Breakdowns were inevitable, making repairs a vital skill. Travelers often hand-dug under wagons to replace broken wheels or axles.

Spare spokes and iron tires were precious cargo, essential for on-the-spot fixing. When parts ran short, local blacksmiths (“dongolas”) were hired.

These repairs demanded collaboration and resilience, illustrating the unpredictability of trail life. Each fix was a lesson in resourcefulness, a testament to human ingenuity in the face of adversity.

10. Daily “Wagons West” Routine

The day began at dawn, a symphony of activity as everyone pitched in. Animals were untied and yoked, while breakfast signaled the start of another long march.

Women and children packed lunches, typically jerky and hardtack, filling canteens for the journey ahead. Men led the teams, navigating toward the next water source.

This routine was a ritual of resilience, a dance with nature and time. Each day’s chores forged bonds and tested wills, shaping the rhythm of life on the trail.

11. Dealing with Dust and Cholera

Dust storms plagued travelers, leading to ailments like “dust pneumonia.” Yet, cholera posed the deadliest threat, lurking in contaminated water supplies.

It claimed countless lives, a grim reminder of the trail’s hazards. Medical supplies were limited, and quarantine was often the only recourse.

These challenges demanded vigilance and community support, underscoring the harsh realities of wagon life. Each dusty breath and tainted drink emphasized the precariousness of survival on the trail.

12. Night Watches and Prairie Skies

As night fell, camps arranged in protective circles became bastions of safety. Night watches patrolled for predators like wolves or bears and monitored the weather.

The expansive prairie sky was a canvas of stars, offering a rare beauty amidst hardship. The Milky Way often provided the only illumination.

This nightly ritual fostered a sense of security and wonder, a time for reflection under celestial splendor. It was a reminder of the vastness and mystery of the frontier.

13. Trading with Native Guides

Engaging with Native guides was both a necessity and a cultural exchange. These guides possessed invaluable knowledge of water sources and safe passages.

Trade involved exchanging goods like moccasins for knives or hides for flour. Building good relations was as crucial as navigating the physical landscape.

These interactions enriched the journey, highlighting cooperation over conflict. They added a layer of complexity and depth to the pioneer experience, merging diverse paths on the trail.

14. Social Bonds: Wagon Trains as Mobile Communities

Wagon trains were more than traveling groups; they were mobile communities. Potluck dinners, shared repairs, and makeshift schools for children fostered a sense of belonging.

When illness struck, community spirit shone through as neighbors carried the sick on stretchers between wagons. These shared experiences cemented social bonds.

Life on the trail was about mutual reliance and camaraderie, turning strangers into family. It was a journey of collective resilience, defined by shared hardships and joys.

15. Reaching the Destination: Triumph and New Beginnings

After months of relentless travel, reaching the destination was a triumph marked by fresh water, garden vegetables, and homemade bread.

The end of the trail signified new beginnings, as settlers laid down roots, turning dreams into reality. It was a moment of collective celebration and reflection.

This arrival was both an end and a beginning, a testimony to human spirit and perseverance. The journey forged new communities, laying the foundation for future generations in the American West.