The Great Fire of 1910 roared through Idaho, Montana, and Washington, consuming three million acres and claiming 87 lives in just two days. This catastrophic event, also known as the ‘Big Blowup,’ became a turning point in American forestry history. The flames that destroyed towns and forests alike sparked dramatic changes in how our nation approaches wildfire management, creating ripple effects that continue to shape policy and practice more than a century later.

1. Birth of Aggressive Fire Suppression

Flames that once roamed freely through America’s forests suddenly became public enemy number one. Before the 1910 disaster, many forestry experts considered wildfire a natural process, sometimes beneficial for forest health.

The devastating losses changed everything. Forest Service leaders, traumatized by the death toll and destruction, embraced total fire suppression as their primary mission. Every spark, no matter how small or remote, would be extinguished immediately.

This fundamental shift created the foundation for modern firefighting, prioritizing human safety and property protection above all else.

2. The ’10 a.m. Policy’ Revolution

Forest Service Chief Forester Roy Headley formalized America’s war on wildfire in 1935 with a remarkably ambitious directive. His ’10 a.m. policy’ demanded that every wildfire be contained by 10 a.m. the day after discovery – no exceptions.

Rangers mobilized with military precision when smoke appeared on the horizon. This aggressive approach dominated wildfire management for nearly 50 years, reshaping America’s relationship with forest fires.

The policy reflected the lingering trauma of 1910’s devastation and solidified the Forest Service’s identity as fire’s sworn enemy.

3. Smokey Bear’s Powerful Legacy

America’s most famous bear owes his existence to the Great Fire’s aftermath. The Forest Service, haunted by 1910’s devastation, launched Smokey’s iconic campaign in 1944 to enlist citizens in preventing forest fires.

His simple message – ‘Only YOU can prevent wildfires’ – became one of the most successful public service announcements in history. Generations of Americans grew up with Smokey’s gentle warnings about campfire safety and proper cigarette disposal.

The campaign effectively transformed public consciousness, making wildfire prevention a personal responsibility for every American venturing outdoors.

4. Congressional Funding Explosion

Money flowed like water after the 1910 disaster reshaped political priorities. Congress, shocked by the devastation, nearly doubled the Forest Service’s budget in direct response to the fire.

This financial windfall transformed a fledgling agency into a powerful force for conservation and fire management. New ranger stations appeared across the West, while equipment, personnel, and training programs expanded dramatically.

The funding surge solidified the Forest Service’s authority over public lands and established wildfire management as a critical government function worth significant investment – a precedent that continues today.

5. Military-Style Firefighting Organization

Rangers traded their forestry manuals for military field guides after 1910. The chaotic, uncoordinated response to the Big Blowup revealed the need for military-style organization in fire response.

Firefighting crews adopted strict chains of command, standardized training, and coordinated attack strategies. By the 1940s, elite ‘smokejumpers’ were parachuting into remote fires – a direct evolution of this militarized approach.

Fire camps began operating like forward military bases, with specialized roles for planning, logistics, communications, and frontline attack – a structure that remains the backbone of modern wildfire response.

6. The Revolutionary Pulaski Tool

Forest ranger Ed Pulaski became a hero when he saved most of his 45-man crew during the 1910 inferno by sheltering in an abandoned mine shaft. His harrowing experience inspired him to create something revolutionary.

Pulaski combined an axe blade with a grubbing hoe to create a versatile firefighting tool. Firefighters could now quickly switch between chopping and digging fire lines without changing equipment.

This ingenious invention remains standard issue for wildland firefighters today – a practical legacy of one man’s determination to improve firefighter effectiveness and safety after witnessing devastating losses.

7. Indigenous Knowledge Sidelined

Native American tribes had managed western landscapes with controlled burns for thousands of years before European settlement. These carefully timed fires prevented dangerous fuel buildup while promoting healthy ecosystems.

Forest Service leaders, traumatized by 1910’s destruction, rejected these indigenous practices as primitive and dangerous. Traditional ecological knowledge accumulated over centuries was dismissed in favor of total fire elimination.

This cultural arrogance created a tragic legacy of overgrown forests primed for catastrophic burns – a mistake forest managers would only begin acknowledging decades later as they rediscovered the wisdom of controlled burning.

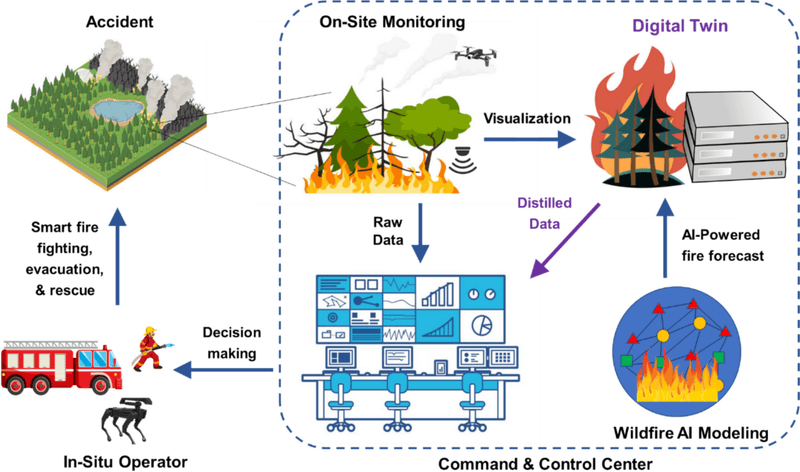

8. Technological Innovation Acceleration

America’s wilderness received unprecedented technological attention following the 1910 disaster. Fire lookout towers sprouted on remote peaks, staffed by vigilant observers scanning for smoke plumes during fire season.

Radio communications networks connected these isolated sentinels to headquarters, dramatically reducing response times. By mid-century, aircraft patrol routes complemented ground observation, while specialized firefighting equipment evolved rapidly.

This technological revolution transformed wildfire detection from a haphazard process dependent on chance sightings to a systematic monitoring network capable of spotting and responding to fires in their earliest, most manageable stages.

9. The Weeks Act’s Lasting Impact

Congressional response to the 1910 catastrophe extended beyond emergency funding. The Weeks Act of 1911 fundamentally transformed American forest management by authorizing federal purchase of private forestlands to protect watersheds and timber resources.

This landmark legislation enabled the creation of eastern national forests and established crucial federal-state partnerships for fire protection. Private landowners gained access to firefighting resources previously limited to federal lands.

The cooperative framework established by the Weeks Act remains the foundation of America’s integrated approach to wildfire management, where multiple agencies coordinate across jurisdictional boundaries to address fire threats.

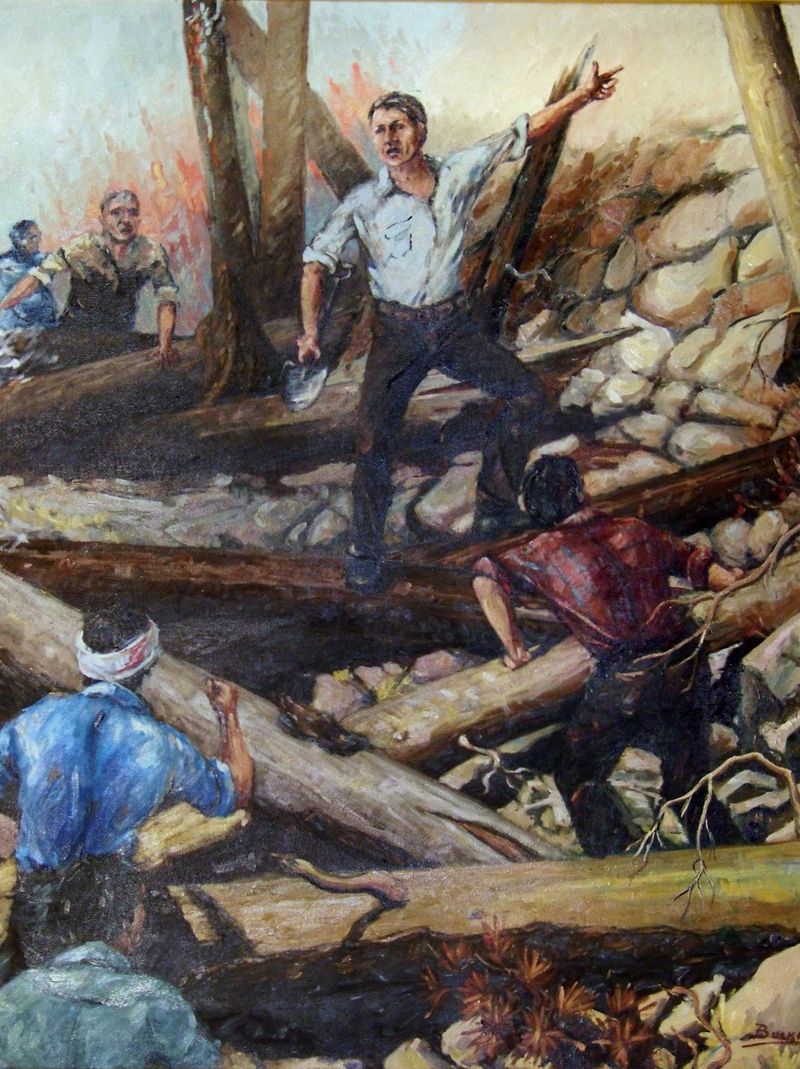

10. Firefighting as National Heroism

Ed Pulaski’s legendary rescue of his crew during the 1910 blaze transformed wildland firefighters into American folk heroes. His story – leading men to safety in an abandoned mine while holding them at gunpoint when they panicked – captured public imagination.

Newspapers celebrated the bravery of those who battled the flames, establishing a tradition of venerating wildland firefighters that continues today. This cultural shift elevated fire suppression from mere labor to patriotic duty and honorable sacrifice.

The heroic narrative created after 1910 helped recruit generations of firefighters willing to risk their lives protecting America’s forests and communities.

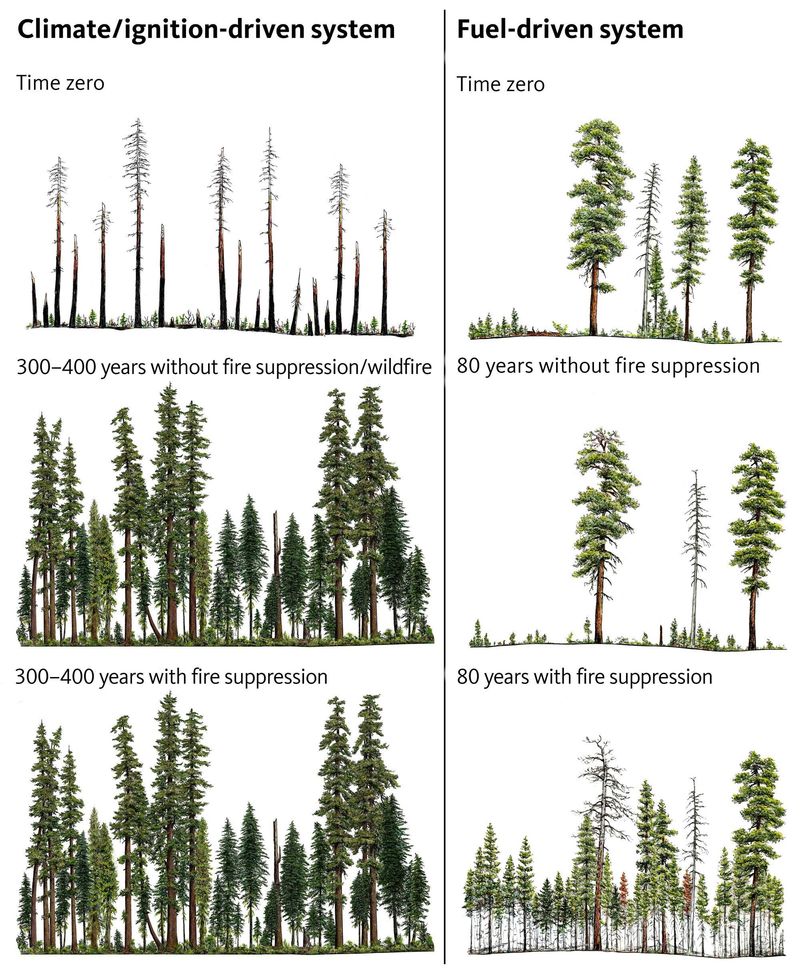

11. The Fuel Buildup Paradox

Success became failure in America’s forests through an ironic twist of ecological consequences. Decades of aggressive fire suppression prevented natural low-intensity burns that historically cleared forest understory.

Forests grew unnaturally dense with fallen branches, brush, and small trees creating perfect ladder fuels. When fires inevitably escaped control, they exploded into crown fires of unprecedented intensity.

Today’s megafires, burning hotter and faster than historical blazes, represent the unintended legacy of policies born from the 1910 disaster – a cautionary tale about disrupting natural cycles without understanding their ecological importance.

12. Return to Prescribed Fire Practices

Forest managers experienced a humbling revelation in the 1970s when they began acknowledging what indigenous people had known for millennia – ecosystems need periodic fire. The pendulum slowly swung back toward controlled burning as ecological understanding improved.

Prescribed fires were reintroduced to reduce dangerous fuel loads and restore forest health. This philosophical shift represented a dramatic departure from the total suppression doctrine established after 1910.

Modern fire management now incorporates indigenous knowledge that was dismissed a century ago, using carefully controlled burns to prevent catastrophic wildfires – essentially returning to practices that predated European settlement.

13. Climate Change Complications

Fire suppression policies created after 1910 assumed a stable climate that no longer exists. Today’s fire managers face longer fire seasons, record-breaking temperatures, and unprecedented drought conditions that transform forests into tinderboxes.

Climate change has amplified the consequences of past suppression policies, creating conditions where fires burn hotter, spread faster, and resist control efforts. The management approach born from the Big Blowup now struggles against meteorological realities its creators never imagined.

Adapting fire management for this new climate reality represents perhaps the greatest challenge since 1910, requiring fundamental reconsideration of century-old assumptions about fire behavior and control.

14. Scientific Research Revolution

The 1910 disaster sparked America’s first serious scientific examination of wildfire behavior. Early researchers sought to understand how fires spread, what conditions created extreme fire behavior, and how different suppression techniques performed.

By mid-century, formal fire science emerged as a distinct discipline with dedicated laboratories, experimental burns, and sophisticated computer modeling. Researchers studied everything from fire ecology to smoke chemistry, creating an entirely new field of scientific inquiry.

This knowledge explosion continues today, with fire science informing management decisions through better understanding of fire’s ecological role and behavior under varying conditions.

15. Policy Flexibility Lessons

The century following the Great Fire taught forest managers the dangers of rigid, one-size-fits-all approaches to wildfire. Modern policy emphasizes flexibility, allowing different responses based on ecological needs, human safety concerns, and resource values.

Some fires now receive full suppression while others are managed for resource benefits or simply monitored. This nuanced approach recognizes fire as a complex natural process rather than simply an enemy to defeat.

The evolution from the absolutist policies created after 1910 to today’s adaptive management represents perhaps the most profound legacy of the Big Blowup – learning that nature requires respect rather than domination.