Uyghur cuisine represents the rich cultural heritage of the Turkic Muslim minority in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region.

These flavorful dishes combine Central Asian, Middle Eastern, and Chinese influences, creating a unique culinary tradition built around hand-pulled noodles, grilled meats, and freshly baked breads.

As China attempts to control the narrative around Uyghur culture, many of these traditional foods remain unknown to the outside world, despite their incredible flavors and historical significance.

1. Lagman (Hand-Pulled Noodles)

These mesmerizing hand-pulled noodles showcase the remarkable skill of Uyghur cooks who stretch and swing dough into long, elastic strands. The chewy noodles serve as the foundation for a vibrant topping of stir-fried meat and vegetables seasoned with cumin, star anise, and chili. Families pass down lagman-making techniques through generations, with each cook developing their signature pulling style. The dish represents both everyday sustenance and celebratory feasting in Uyghur communities. Traditionally eaten communally, lagman exemplifies how food preserves cultural identity even as the Chinese government restricts other expressions of Uyghur heritage.

2. Polo (Uyghur Pilaf)

Fragrant rice cooked with tender chunks of lamb, carrots, onions, and a blend of aromatic spices creates the centerpiece of Uyghur gatherings. Yellow from turmeric and saffron, polo fills homes with an irresistible aroma that signals celebration and hospitality. Every Uyghur household guards their unique polo recipe, with subtle variations in spice ratios and cooking techniques. The dish requires patience – first browning the meat, then layering ingredients carefully before allowing everything to steam together. Serving polo to guests represents the highest form of Uyghur hospitality, a tradition that strengthens community bonds despite increasing pressures on cultural practices.

3. Kawap (Lamb Skewers)

Sizzling over open flames, these skewers of marinated lamb chunks represent the soul of Uyghur street food. Vendors fan charcoal grills while sprinkling cumin, chili, and salt over the cooking meat, creating clouds of fragrant smoke that draw hungry crowds. The meat – usually from fat-tailed sheep – alternates with pieces of lamb fat that melt during cooking, basting the meat naturally. Each bite delivers a perfect balance of charred exterior and juicy interior. Beyond mere sustenance, kawap embodies the nomadic heritage of the Uyghur people, who traditionally raised livestock on the region’s vast grasslands before Chinese policies restricted their movement.

4. Samsa (Meat-Filled Pastry)

Golden-brown pastries studded with black sesame seeds emerge from traditional clay ovens, their flaky exteriors hiding savory fillings of minced lamb, onions, and spices. Bakers slap the raw dough triangles directly onto the inner walls of the tonur oven, where intense heat creates the perfect crispy-yet-tender texture. Morning markets throughout Xinjiang feature vendors selling fresh samsa, wrapped in paper for busy workers to enjoy on the go. The portable nature of these pastries made them ideal for the historically nomadic Uyghur lifestyle. Each region boasts its own samsa variation – some featuring pumpkin or wild herbs alongside the meat filling.

5. Goshnaan (Uyghur Meat Pie)

Goshnaan combines two Uyghur staples – bread and meat – into one satisfying meal. Minced lamb mixed with onions, spices, and sometimes pumpkin gets sealed inside flatbread dough before being pan-fried to golden perfection. Unlike samsa, goshnaan cooks on a flat griddle, creating a different texture – crispy on the outside with a slightly chewy interior. Skilled cooks flatten the dough remarkably thin while keeping the filling contained, a technique requiring years of practice. During winter festivals, extended families gather to make goshnaan together, with elders teaching younger generations the proper techniques – a cultural transmission that persists despite government efforts to standardize food practices.

6. Leghmen (Fried Noodles)

Not to be confused with lagman, leghmen features similar hand-pulled noodles but stir-fried rather than served in broth. The noodles take on a slightly smoky flavor from the hot wok, while retaining their characteristic chewiness that Uyghurs prize. Vegetables like bell peppers, tomatoes, and garlic chives add vibrant color and texture, complementing the tender pieces of lamb or beef. Cooks toss everything together with a sauce featuring black vinegar, which cuts through the richness of the meat. Street vendors throughout Kashgar and Urumqi compete for customers with their distinctive leghmen recipes, each claiming their spice blend or noodle technique produces the most authentic version.

7. Nan (Uyghur Flatbread)

The stamp of Uyghur identity comes in the form of these distinctive round flatbreads, their centers decorated with intricate patterns made by special wooden stamps before baking. More than just food, nan carries spiritual significance – elders bless it before eating, and breaking bread together seals friendships and business deals. Bakers rise before dawn to prepare the dough, which gets slapped onto the scorching walls of clay ovens. The intense heat creates a contrast between the crisp exterior and soft interior that defines perfect nan. Different regions produce unique variations – Kashgar nan features a thicker, softer texture while Turpan’s version is thinner and crispier with more oil.

8. Toghach (Stuffed Fried Bread)

Crispy on the outside yet fluffy within, toghach offers a delightful textural experience as teeth break through the golden crust to discover savory fillings. Unlike its baked cousins, this bread gets shallow-fried, creating a distinctive richness that makes it particularly satisfying during cold Xinjiang winters. Fillings vary seasonally – spring versions might include wild mountain herbs and young lamb, while autumn toghach features pumpkin and dried fruits. The bread’s portable nature made it perfect for shepherds and travelers crossing the ancient Silk Road. Families guard their toghach recipes jealously, with subtle differences in dough hydration and frying temperature creating signature versions unique to each household.

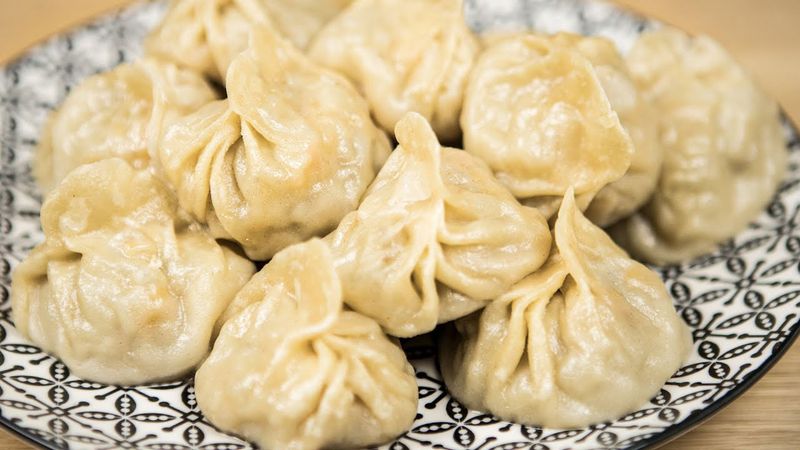

9. Yutaza (Steamed Dumplings)

Steam rises when the lid lifts from bamboo baskets filled with these delicate dumplings, their thin wrappers translucent enough to hint at the filling within. Unlike Chinese jiaozi, Uyghur yutaza features distinctive spice blends including cumin, black pepper, and coriander mixed with the minced lamb. Making yutaza becomes a communal activity, with family members gathering around tables to fold dumplings while sharing stories and news. The repetitive motion of pleating the wrappers creates a meditative atmosphere that strengthens family bonds. Traditionally served with a dipping sauce of black vinegar, chili oil, and garlic, yutaza exemplifies how Uyghur cuisine balances neighboring culinary influences while maintaining its unique character.

10. Korma Chop (Fried Meat Chops)

Sizzling hot and intensely savory, korma chop features thin slices of lamb quickly fried with onions, garlic, and a blend of spices that create a caramelized exterior while keeping the meat tender. The dish exemplifies the Uyghur preference for quick cooking methods that preserve the natural flavors of their prized lamb. Unlike Chinese stir-fries that use soy sauce, korma chop relies on the meat’s natural juices combined with cumin, dried red chilies, and sometimes a touch of tomato for depth. Cooks toss the ingredients continuously in well-seasoned woks that impart a subtle smoky flavor. Served over rice or with fresh nan, korma chop provides a quick but satisfying meal for Uyghur families.

11. Boso Lagman (Fried Lagman Noodles)

Transforming leftover lagman into something entirely new, boso lagman demonstrates the resourcefulness central to Uyghur cooking. The previously boiled hand-pulled noodles get a second life when stir-fried until slightly crispy, then tossed with eggs, vegetables, and whatever meat remains from yesterday’s meal. The dish exemplifies how Uyghur families traditionally wasted nothing, creating delicious meals from leftovers. Many claim boso lagman tastes even better than the original dish, as the noodles absorb more flavor during their second cooking. Modern Uyghur restaurants now prepare boso lagman from scratch rather than using leftovers, testament to its popularity beyond its practical origins.

12. Tugur (Boiled Dumplings)

Simple yet satisfying, tugur dumplings bob in boiling water until their thin wrappers become tender while protecting the flavorful filling inside. Unlike their steamed cousins, these boiled dumplings develop a silkier texture that melts in the mouth. Traditionally stuffed with lamb and onions seasoned with black pepper and coriander, modern variations might include pumpkin, wild herbs, or even sweet fillings for dessert versions. The cooking water transforms into a light broth served alongside the dumplings, with nothing going to waste. During winter festivals, extended families produce hundreds of tugur, storing extras outside in the freezing temperatures – nature’s refrigeration in the harsh Xinjiang climate.

13. Qatig (Yogurt Dish)

Tangy homemade yogurt serves as both refreshing beverage and cooling counterpoint to the rich, spiced dishes of Uyghur cuisine. Made from sheep or cow’s milk cultured with heirloom bacterial strains passed down through generations, qatig develops a distinctive flavor profile unique to each family. Summer versions feature qatig drizzled with local honey and topped with walnuts or mulberries. The contrast between the tart yogurt and sweet toppings creates a perfect balance, especially refreshing during hot desert afternoons. Beyond its culinary role, qatig holds cultural significance in traditional medicine, believed to promote digestive health and longevity – wisdom that modern science now confirms through research on probiotics.

14. Manta (Steamed Buns)

Large, palm-sized dumplings steam gently in stacked wooden baskets, their pleated tops creating distinctive spiral patterns that mark them as manta. Unlike Chinese baozi, these Uyghur steamed buns feature thinner dough and focus almost exclusively on meat fillings rather than vegetables. The perfect manta achieves a delicate balance – dough thin enough to cook quickly yet strong enough to contain the juicy filling of lamb, onions, and pumpkin. Skilled cooks create elaborate pleating patterns that aren’t just decorative but functional, helping steam penetrate evenly. Traditionally eaten by hand, manta often accompanies milk tea as a substantial breakfast that sustains farmers and herders through long workdays in Xinjiang’s challenging climate.

15. Chuchure (Soup with Dumplings)

Small crescent-shaped dumplings float in a clear, aromatic broth, creating a soup that warms body and soul during harsh Xinjiang winters. Unlike other Uyghur dumplings, chuchure features a thinner wrapper and smaller size, allowing them to cook directly in the broth rather than separately. The soup base develops depth from slow-simmered lamb bones, star anise, and black cardamom. Fresh herbs like coriander and wild garlic chives get stirred in just before serving, their bright flavors balancing the rich broth. Families traditionally gather around steaming bowls of chuchure during the first snowfall of winter, the communal meal symbolizing togetherness during the coming cold months.

16. Zhuafan (Sticky Rice with Meat)

Jewel-like carrots, raisins, and apricots glisten among grains of sticky rice, creating a colorful dish that bridges the gap between savory and sweet. Tender chunks of lamb enriched with rendered fat provide savory depth, while the fruits contribute natural sweetness without overwhelming the palate. Preparing zhuafan requires patience – first steaming the rice, then layering it with partially cooked ingredients before final steaming that allows flavors to meld perfectly. The dish frequently appears at weddings and celebrations, its abundance symbolizing wishes for prosperity. Regional variations reflect local ingredients – southern Xinjiang versions feature more dried fruits, while northern preparations include more root vegetables.