Jazz isn’t just music – it’s a force that changed America forever.

Born in New Orleans and raised in speakeasies, dance halls, and clubs across the nation, this uniquely American art form challenged social norms and transformed culture in ways most history books barely mention.

While textbooks focus on wars and presidents, jazz was quietly reshaping race relations, gender roles, and global perceptions of American identity.

1. America’s First Global Sound

Long before rock stars toured the world, jazz musicians were America’s first cultural ambassadors. New Orleans rhythms echoed through Paris cafés and Tokyo dance halls as early as the 1920s, creating America’s first musical export phenomenon.

Local sounds born in Louisiana spread across oceans, captivating listeners who had never set foot on American soil. Europeans embraced this fresh sound while their classical traditions seemed increasingly stuffy and old-fashioned.

Countries around the world formed their own jazz scenes, adapting the American innovation to their cultural contexts. This musical diplomacy happened organically, powered by recordings and touring musicians rather than government programs.

2. Black Artists on the Global Stage

While facing segregated bathrooms and “whites only” restaurants at home, Black jazz pioneers like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington received royal treatment abroad. European audiences celebrated these artists as cultural geniuses while Jim Crow laws restricted their basic rights in America.

The contrast was stark and revealing. In Paris, Armstrong dined in the finest restaurants; back home, he often couldn’t enter through the front door of venues where he performed.

This international acclaim created an uncomfortable contradiction that highlighted America’s racial hypocrisy. How could a nation claim democratic values while denying full citizenship to the very artists representing American culture worldwide?

3. Breaking Segregation’s Barriers

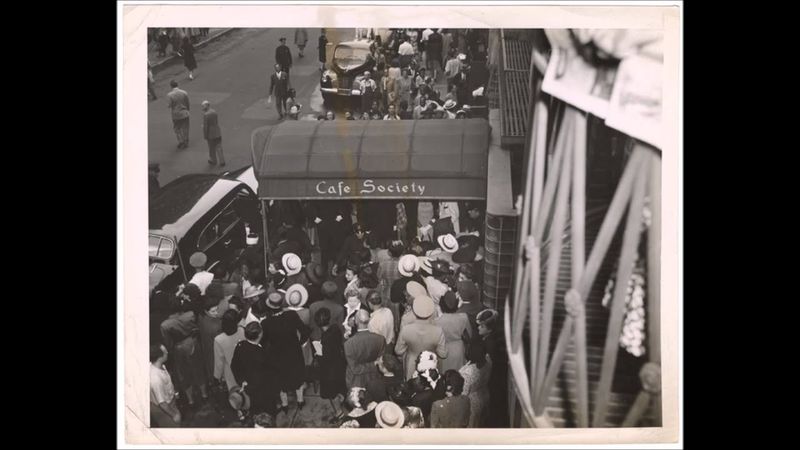

When New York’s Cafe Society opened in 1938, something revolutionary happened: Black and white patrons sat side by side enjoying music together. This Greenwich Village club boldly declared “the wrong side of the tracks” as its address, mocking segregation while creating an integrated space decades before civil rights laws.

Jazz venues became islands of integration in a segregated America. The music itself demanded this mixing – white musicians learned from Black innovators, creating collaborative spaces where talent mattered more than skin color.

Even in the Deep South, the back rooms of jazz clubs sometimes witnessed forbidden mingling across racial lines, united by a shared passion for this boundary-breaking music.

4. Redefining American Identity

Jazz embodied America’s cultural melting pot before that concept was widely embraced. Its DNA contained African rhythms, European harmonies, Caribbean influences, and blues expressions – all transformed through distinctly American improvisation.

This musical fusion challenged the dominant narrative that American culture was primarily European in origin. Jazz insisted on recognizing African American contributions as central to national identity, not peripheral.

When asked what American music was, conductor Leonard Bernstein simply replied: “Jazz.” This recognition forced a rethinking of what being American meant – moving from a narrow definition based on European heritage toward something more inclusive, dynamic, and reflective of the nation’s diverse origins.

5. Fuel for the Harlem Renaissance

The rhythmic innovations of jazz musicians directly inspired poets like Langston Hughes, who crafted verse that swung and syncopated like the music filling Harlem’s nightclubs. Artists captured the vibrant nightlife in paintings while writers documented this cultural explosion in novels and essays.

Jazz provided both soundtrack and subject matter for this unprecedented flowering of Black creativity. The music’s improvisational spirit encouraged artists in all mediums to experiment with form and express themselves with new freedom.

Money flowing into jazz venues helped fund other artistic ventures, creating an economic ecosystem for Black creativity. This renaissance represented the first time mainstream America was forced to acknowledge Black cultural achievement on a massive scale.

6. A Weapon in the Cold War

When Soviet propaganda highlighted American racism, the State Department responded by sending jazz ambassadors abroad. Dizzy Gillespie’s 1956 Middle East tour became a diplomatic triumph as his bebop innovations demonstrated American creativity while his integrated band showcased racial cooperation.

The strategy contained a profound irony: musicians who faced discrimination at home were deployed to improve America’s image abroad. Dave Brubeck canceled 23 out of 25 college concerts in 1960 when schools wouldn’t accept his integrated quartet.

Nevertheless, these jazz tours succeeded where traditional diplomacy failed. Audiences who rejected American political messages embraced the music, creating cultural connections that transcended Cold War hostilities and showcased America’s creative freedom despite its social contradictions.

7. The Original Musical Protest

Billie Holiday’s haunting performance of “Strange Fruit” in 1939 marked perhaps the first explicit protest song in American popular music. Her devastating portrayal of Southern lynching shocked audiences years before protest music became a recognized genre.

Charles Mingus later confronted segregationist Arkansas governor Orval Faubus with his scathing instrumental “Fables of Faubus.” When Columbia Records refused to record the vocal version with its direct political lyrics, Mingus released it on another label, refusing to be silenced.

Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln’s 1960 “Freedom Now Suite” used extended jazz techniques to express rage at continuing inequality. These jazz protests preceded and influenced the more widely recognized protest music of the folk and rock eras.

8. Women Seizing the Spotlight

Female jazz pioneers fought a double battle – against racial prejudice and gender barriers. Pianist Mary Lou Williams arranged for Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman when women were expected to be singers or novelty acts, not serious instrumentalists or composers.

Billie Holiday transformed the role of vocalist from mere entertainer to profound artist. Her innovative phrasing influenced generations of singers across all genres, proving that interpretation could be as creative as composition.

Nina Simone later used her jazz platform to become the “High Priestess of Soul” and a fearless civil rights activist. These women claimed artistic authority in an era when female ambition was often dismissed, creating templates for women’s leadership that extended far beyond music.

9. The Soundtrack of Civil Rights

When civil rights marchers faced fire hoses and police dogs, jazz provided both inspiration and practical support. Benefit concerts featuring jazz legends raised crucial funds for organizations like CORE and SNCC when mainstream donors feared supporting such “radical” groups.

John Coltrane’s “Alabama” responded directly to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that killed four young girls. His saxophone captured both mournful tribute and determined resilience in the face of terrorism.

At freedom rides and lunch counter sit-ins, activists often hummed jazz standards to maintain courage. The music’s message of perseverance through improvisation – finding new paths when faced with obstacles – became a metaphor for the movement itself, turning musical principles into strategies for social change.

10. Pushing Military Integration

During World War II, Glenn Miller’s Army Air Force Band received attention, but it was the 761st Tank Battalion’s all-Black jazz band that made unexpected history. Their performances for white troops created such positive reception that military leaders were forced to reconsider segregation policies.

The Navy’s reluctant formation of the B-1 Band – its first Black musicians – came after sustained pressure from jazz fans within the ranks. These musicians served double duty, fighting both fascism abroad and discrimination within their own units.

By war’s end, the popularity of integrated jazz performances had helped build momentum for President Truman’s 1948 order to desegregate the armed forces. Music had accomplished what official policy resisted, creating spaces where talent transcended color lines.

11. Reshaping American Literature

Langston Hughes didn’t just write about jazz – he wrote like jazz, with rhythmic innovations and blue notes infusing his poetry. His work “The Weary Blues” captured a pianist’s performance with such authenticity that the poem itself seems to swing.

Jack Kerouac later typed his novel “On The Road” in a three-week creative burst on a continuous scroll of paper, attempting to capture bebop’s spontaneous energy in prose. The Beat Generation’s entire aesthetic borrowed heavily from the improvisational spirit of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Toni Morrison’s novel “Jazz” went further still, structuring its narrative like a jazz composition with multiple voices and perspectives. These literary innovations permanently altered American writing, introducing musical concepts to reshape storytelling itself.

12. Revolutionizing Music Education

Before jazz, music education followed a rigid European model: read the notes, play them exactly as written. Jazz introduced the radical notion that personal expression and improvisation were not just acceptable but essential to musical artistry.

This transformed how music was taught. Conservatories that once rejected jazz now offer degrees in the genre, while grade school music programs incorporate improvisation exercises unimaginable in pre-jazz education.

The Berklee College of Music, founded in 1945 specifically to teach jazz, pioneered this educational revolution. Today, even classical musicians study jazz concepts to develop interpretive skills. This educational transformation represents perhaps jazz’s most lasting contribution – the idea that creating music means finding your own voice, not just reproducing someone else’s.

13. Challenging Gender Norms

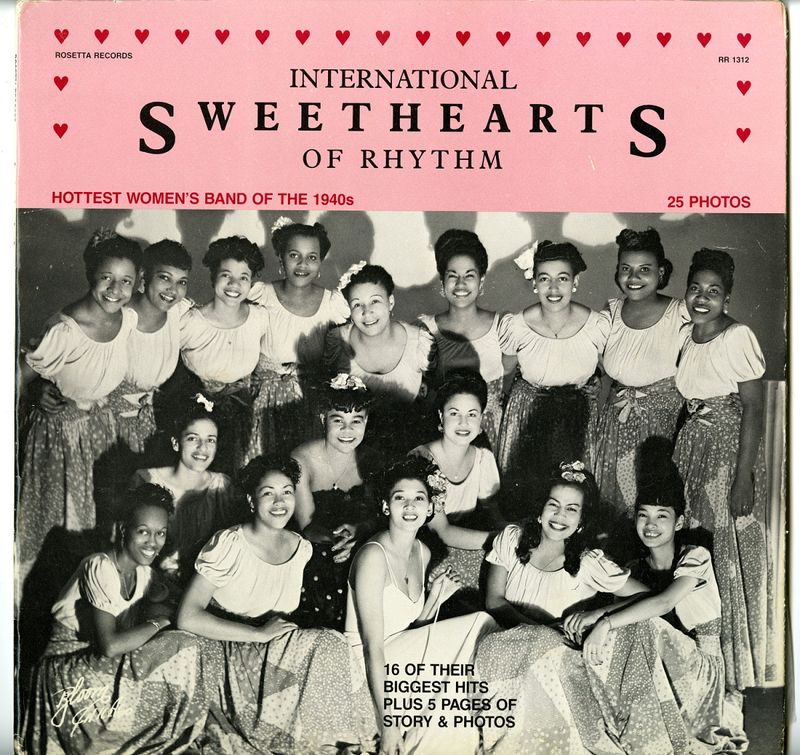

The International Sweethearts of Rhythm defied 1940s expectations by becoming the first integrated all-female jazz band in America. When male musicians were drafted during World War II, these women seized their opportunity, proving they could swing just as hard as the men.

Their success challenged fundamental assumptions about gender capabilities. Drummer Viola Smith’s famous 1942 article “Give Girl Musicians a Break!” argued that women possessed the physical strength and musical skill for any instrument – a revolutionary claim at the time.

Female instrumentalists like Mary Lou Williams and Melba Liston faced constant skepticism but earned respect through undeniable talent. Their persistence opened doors not just in music but in broader society by demonstrating women’s capacity for leadership in previously male-dominated fields.

14. Reinventing Performance Standards

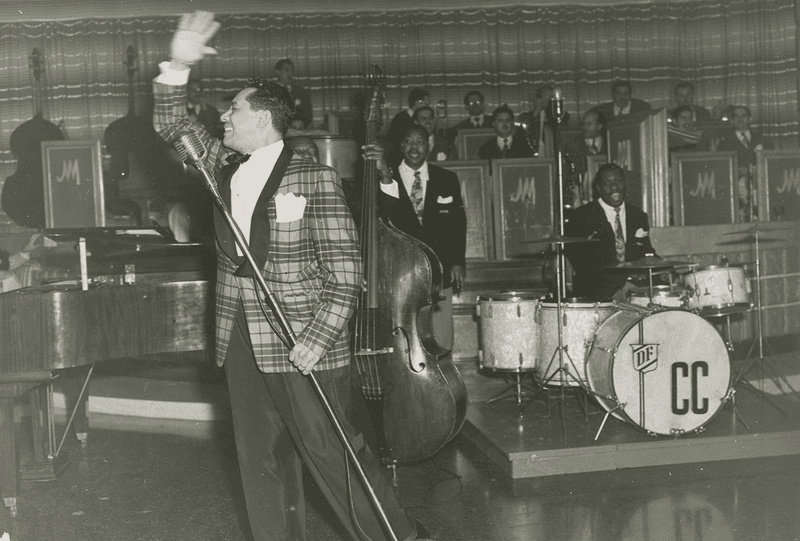

Classical musicians performed as faithful interpreters of composers’ intentions, but jazz musicians introduced a revolutionary concept: the performer as co-creator. Louis Armstrong’s improvisations elevated the soloist from technician to artist, fundamentally changing the relationship between written music and its performance.

This shift rippled through all performance arts. Theater embraced improvisation while dance incorporated individual expression within choreographic frameworks. Even classical soloists began taking more interpretive liberties.

Duke Ellington composed with specific musicians in mind, recognizing their unique voices as essential to the work itself. This elevated respect for individual creativity transformed how audiences understood artistic performance – valuing personal expression over technical perfection and introducing the concept that each performance should be a unique event.

15. Inspiring Civil Rights Leadership

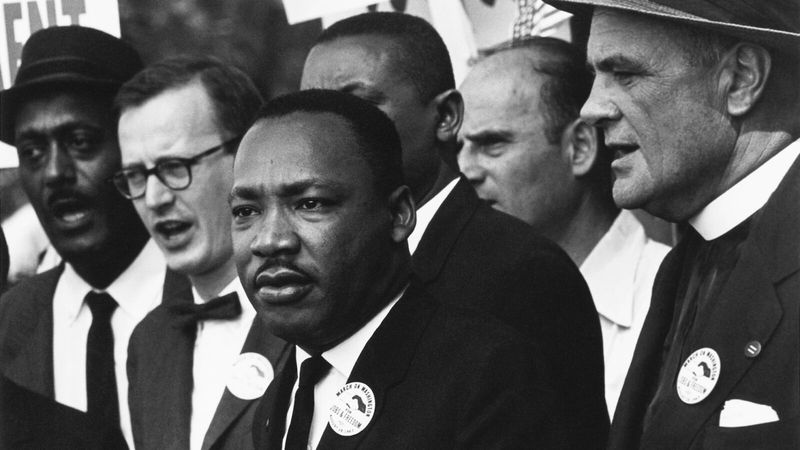

Martin Luther King Jr. spoke often about jazz’s influence on his oratorical style. His speeches employed call-and-response patterns and improvisational flourishes directly borrowed from jazz structures, particularly evident in his “I Have a Dream” speech’s musical cadences.

King specifically praised jazz as a model for social change. “Jazz speaks for life,” he wrote in his opening address for the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, describing how the music demonstrated freedom within structure – exactly what the movement sought in society.

Behind the scenes, jazz artists provided crucial financial support for civil rights organizations. Benefit concerts featuring Nina Simone, Max Roach, and others raised funds when mainstream donors feared association with the movement, creating an economic lifeline that helped sustain the struggle through its most challenging periods.

16. Democratizing Musical Excellence

Before jazz, musical greatness required formal training, expensive instruments, and access to conservatories – privileges largely reserved for the wealthy and white. Jazz upended this hierarchy by recognizing genius in self-taught musicians from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Louis Armstrong, who learned music in a boys’ home after being arrested at age 11, rose to become America’s most influential musician. Billie Holiday, who had no formal training, revolutionized vocal phrasing through pure instinct and emotional intelligence.

This democratization of musical excellence forced a reconsideration of talent itself. Jazz demonstrated that artistic brilliance could emerge from any neighborhood or background, challenging entrenched assumptions about who could create meaningful culture and suggesting that America was wasting tremendous potential through its social inequalities.

17. The History Books’ Missing Chapter

Despite jazz’s profound impact on American culture, most history textbooks reduce it to a brief mention in sections about the 1920s. This erasure reflects ongoing biases about what constitutes “serious” history versus “mere entertainment.”

Standard curricula might devote chapters to military conflicts while ignoring cultural revolutions that transformed everyday life. When jazz appears at all, it’s often separated from mainstream history in specialized sections about music or Black history.

This segregation of jazz from “official” American history perpetuates misconceptions about both the music and the nation itself. By marginalizing jazz’s role in shaping American identity, history books present an incomplete and fundamentally flawed narrative that diminishes the contributions of African Americans to national culture.