They’re the ultimate frontier legends—Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the duo who “discovered” the West and carved a path to the Pacific. Or so we were told. But the truth behind the Lewis and Clark expedition is far more complicated—and in many ways, totally different from the heroic tale found in textbooks. Here are 19 myths and misconceptions about Lewis and Clark that simply don’t hold up under scrutiny.

1. They Were the First Americans to Explore the West

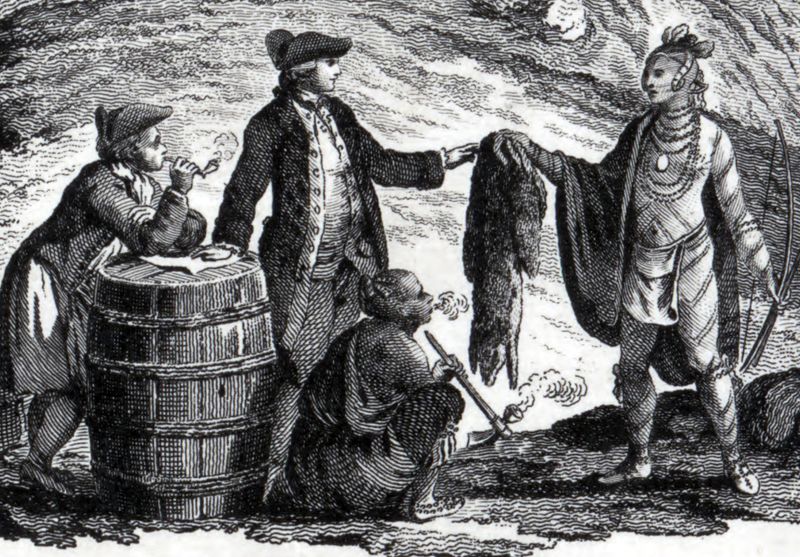

Nope. Long before Lewis and Clark, fur traders, trappers, and missionaries had already explored parts of the American West—many with the help of Native tribes. These early explorers laid the groundwork for future American expansion, often relying on Indigenous knowledge to navigate the challenging terrain. Their journeys may not have been as famous, but they were no less significant.

2. They Traveled Alone

The expedition wasn’t just two brave men against the wild—it included over 40 people, known as the Corps of Discovery, plus Sacagawea, her baby, and even a dog named Seaman. This diverse team worked together to face the unknown challenges of the West. Their unity was a key factor in the journey’s success.

3. They Discovered the Rocky Mountains

False again. Native Americans had known about and crossed the Rockies for centuries. Spanish explorers had also mapped parts of them decades earlier. The Rockies were a well-trodden and well-known landscape long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark.

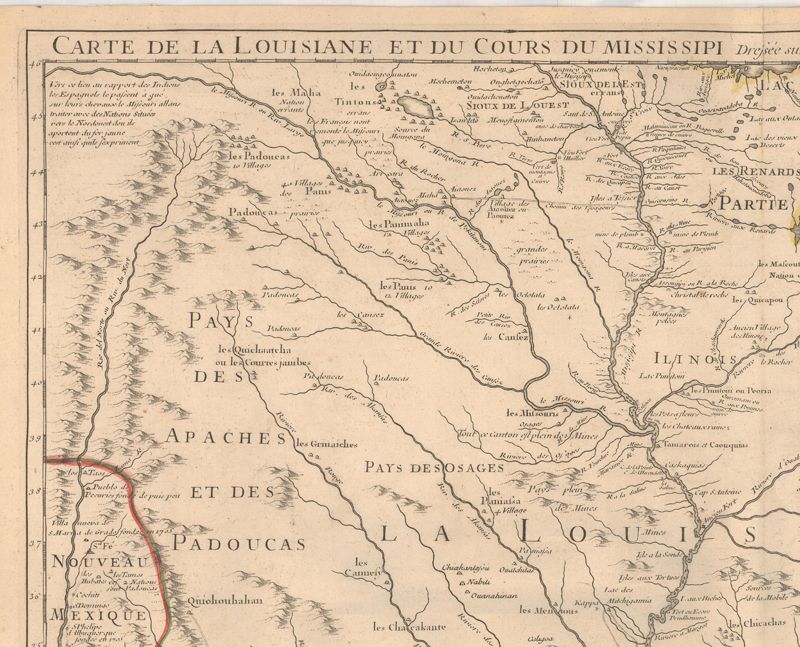

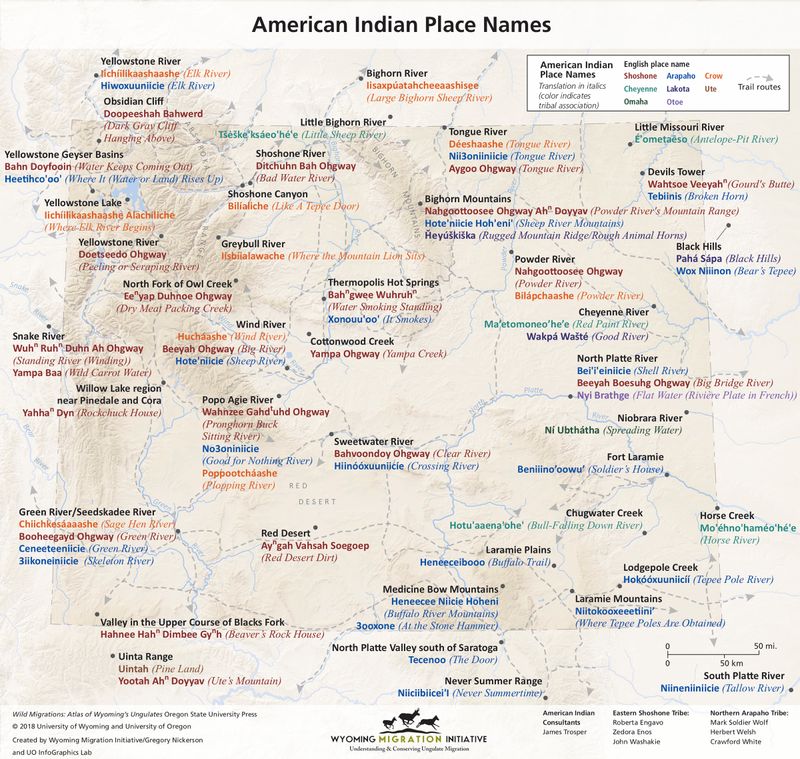

4. They Mapped Everything from Scratch

While the expedition produced important maps, they relied heavily on Indigenous knowledge. Many of their most accurate maps came directly from tribal leaders. The collaboration between cultures was essential for creating detailed cartography of the region.

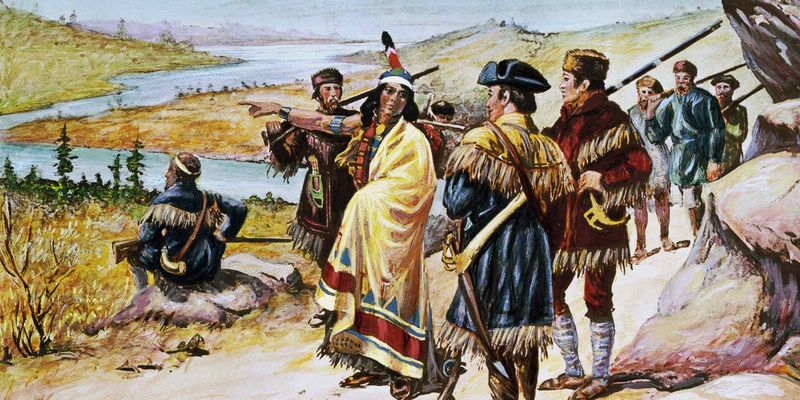

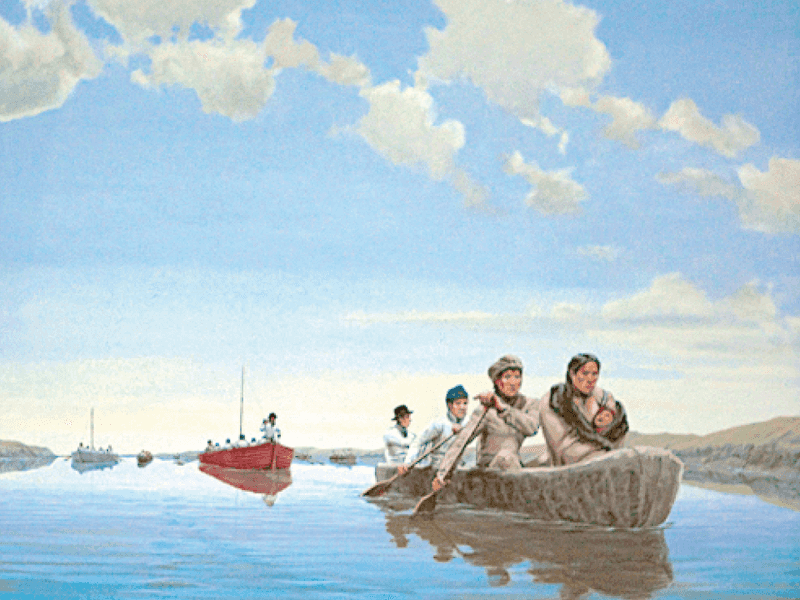

5. Sacagawea Was a Tour Guide

Hollywood loves this myth. In reality, Sacagawea was more of an interpreter and symbol of peace. Her presence helped the expedition avoid hostile encounters—but she wasn’t leading the way with a map in hand. Sacagawea’s role was crucial, yet different from the popular narrative.

6. They Never Got Lost

They absolutely did. The expedition became disoriented multiple times, especially in the Bitterroot Mountains, where they nearly starved. Getting lost was a part of exploring uncharted territories, and they faced it with determination.

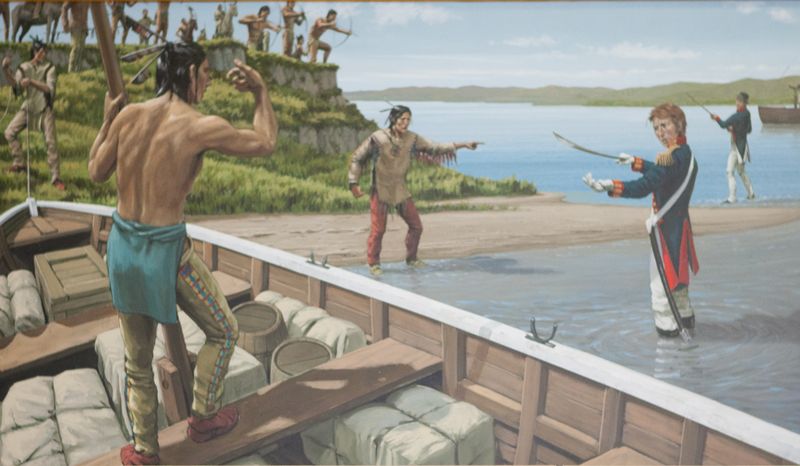

7. They Were Always Welcomed by Native Tribes

Some tribes were friendly, others were cautious, and a few were hostile. Diplomatic encounters were delicate and often tense—far from a guaranteed welcome. These interactions required careful negotiation and understanding from both sides.

8. It Was a Military Operation

Technically, yes—but not in the way people think. While Lewis and Clark were Army officers and operated under military protocol, the mission’s purpose was scientific, diplomatic, and exploratory—not conquest. Their task was to learn and report, not to conquer.

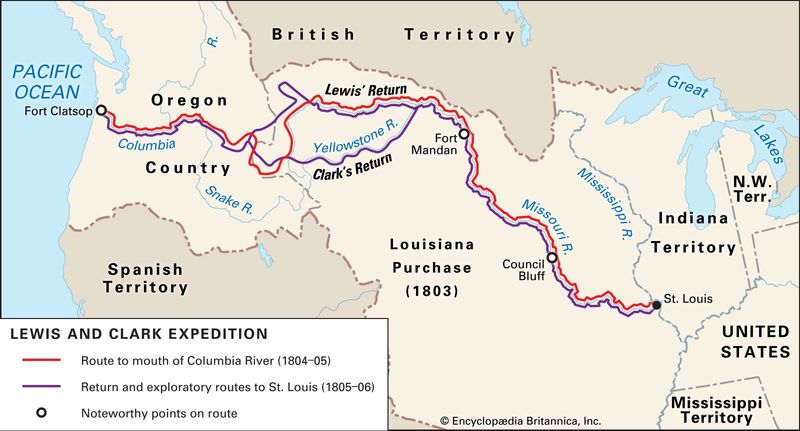

9. They Reached the Pacific and Turned Around

Actually, they stayed near the coast for months. They built Fort Clatsop in present-day Oregon and endured a brutal, wet winter before heading back. This extended stay was crucial for rest and preparation for the return journey.

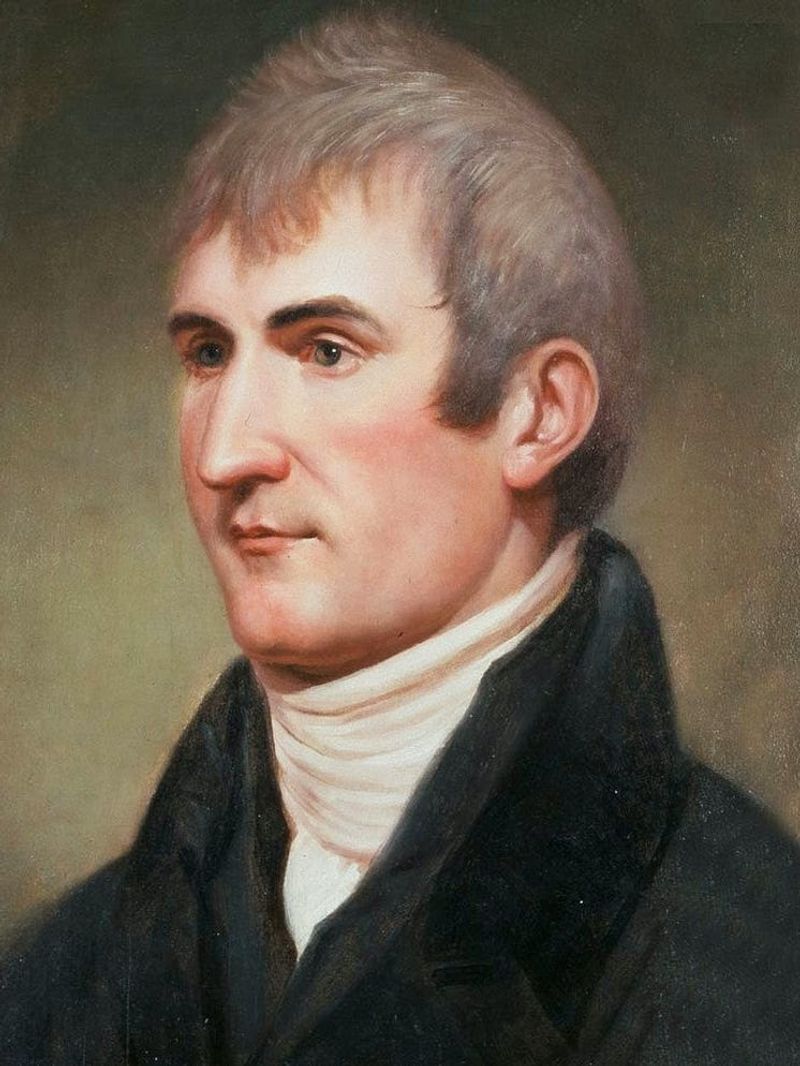

10. Clark Was the Leader

Many assume Clark led the mission, but it was Meriwether Lewis who was chosen by President Jefferson and held the higher rank. Clark was brought on later as co-leader, though they shared duties almost equally. Their partnership was central to the expedition’s achievements.

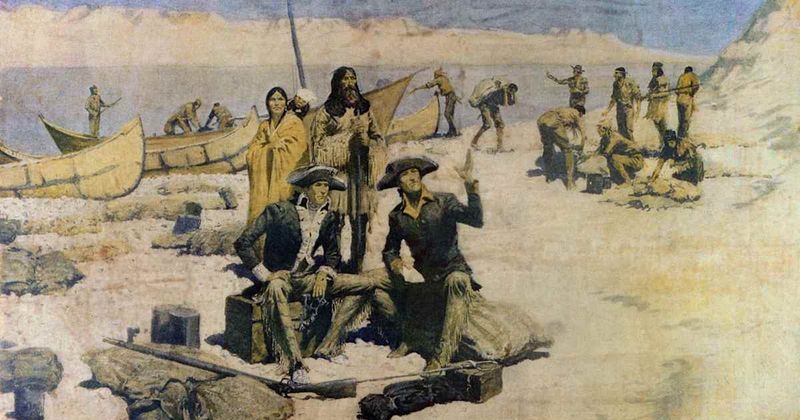

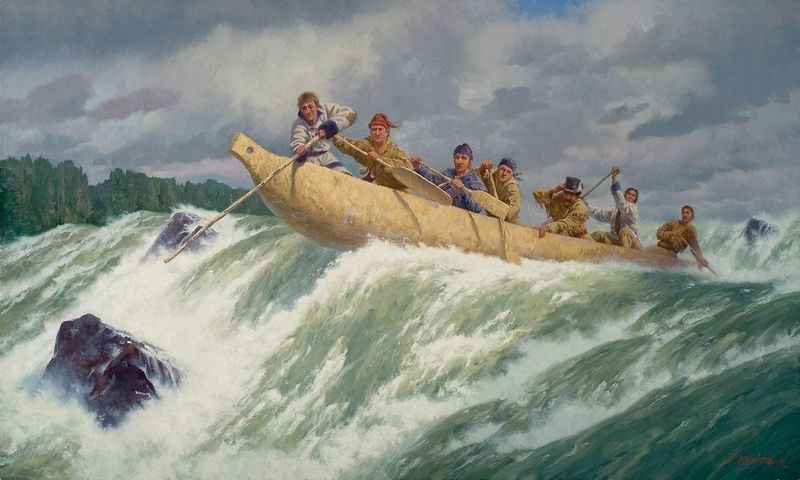

11. They Traveled by Horse

Only sometimes. The Corps primarily traveled by keelboat and canoe. They didn’t even acquire horses until much later—often borrowing them from Shoshone and Nez Perce tribes. Waterways were their main routes for much of the journey.

12. They Had No Scientific Goals

Wrong—President Jefferson specifically charged Lewis with documenting plants, animals, geography, and weather. They collected hundreds of specimens never before seen by Americans on the East Coast. Their scientific contributions were a major outcome of the expedition.

13. They Named Everything

Many of the rivers and mountains already had names—Indigenous ones. Lewis and Clark renamed places to honor U.S. politicians or friends, often erasing Native histories in the process. This practice reflects the complex legacy of exploration and naming.

14. The Expedition Was Always Under Control

They faced mutiny, desertion, illness, and even court-martials. At one point, a corporal was whipped 100 times for theft. The journey was fraught with challenges that tested their leadership and resolve.

15. They Found a Northwest Passage

That was the dream, but it didn’t happen. They hoped for a water route linking the Missouri River to the Pacific—but discovered the Rocky Mountains made that impossible. The myth of the Northwest Passage was one of many shattered ambitions.

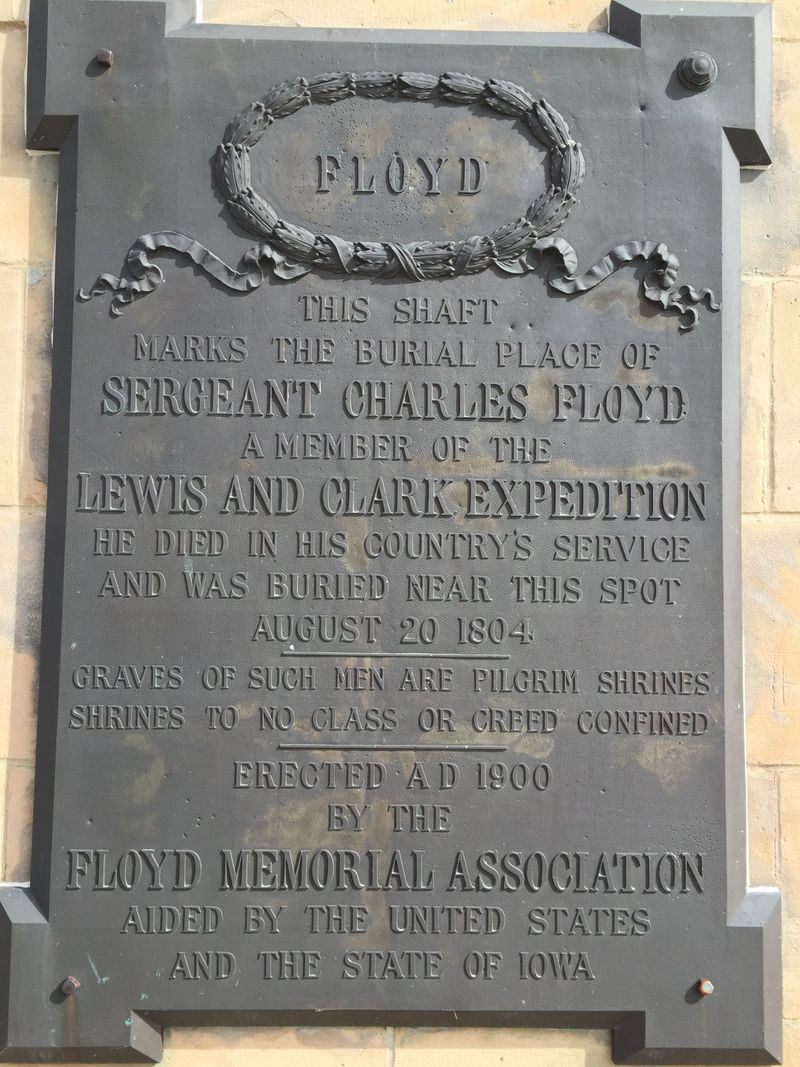

16. Everyone Survived the Trip

Not true. One member, Sergeant Charles Floyd, died early on—likely from a ruptured appendix. Remarkably, he was the only fatality on the multi-year journey. His death was a somber reminder of the expedition’s inherent risks.

17. Sacagawea Was Lewis’s Lover

There’s zero historical evidence for this romantic myth. Sacagawea was married to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trapper, and was likely just a teenager at the time. Her real story is one of resilience and cultural bridging, not romance.

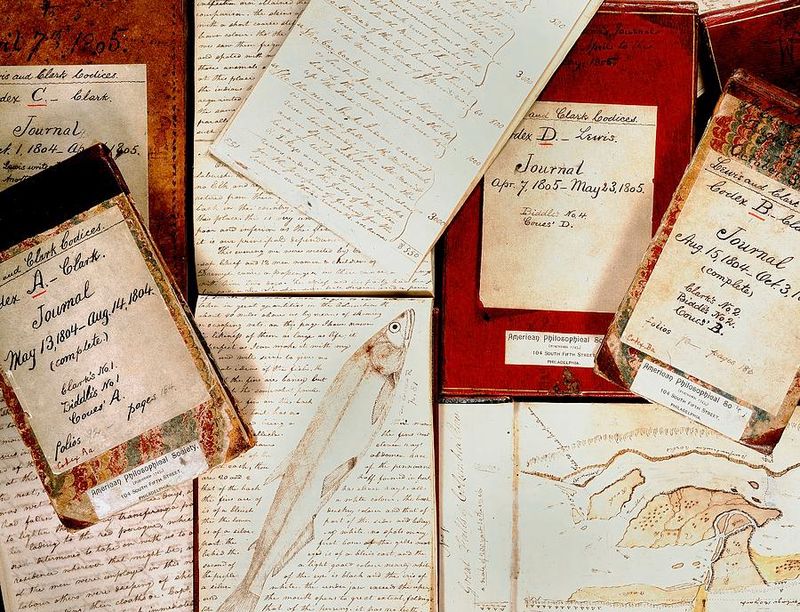

18. Their Journals Were Published Immediately

Lewis’s journals didn’t appear in full until years after his death. Editing, politics, and delays meant the public didn’t get the full story for decades. Despite the delays, these writings eventually became a vital record of the American frontier.

19. Meriwether Lewis Lived Happily Ever After

Tragically, Lewis died just a few years later, under mysterious circumstances. Some believe it was suicide; others think it was murder. The truth remains unknown, casting a shadow over his legacy.