Life in 19th century America was filled with mystery and uncertainty. Before modern science could explain natural phenomena, people relied on superstitions to make sense of their world and protect themselves from misfortune. These beliefs weren’t just casual concerns—they were deeply embedded in daily routines and decisions, shaping how Americans lived, worked, and interacted with one another.

1. Ladder Avoidance

Ordinary ladders transformed into symbols of doom for 19th century Americans. Though partly rooted in practical safety concerns, the superstition carried deeper spiritual meanings that genuinely frightened people.

Many believed walking under a ladder broke the sacred triangle formed between the ladder, wall, and ground—a shape representing the Holy Trinity. Others connected it to medieval gallows, where executioners climbed ladders while the condemned stood below.

If someone accidentally passed beneath a ladder, they’d perform specific rituals to counter the bad luck: crossing fingers until spotting a dog, spitting three times through the ladder’s rungs, or making the sign of the cross. These weren’t casual habits but desperate attempts to avoid misfortune.

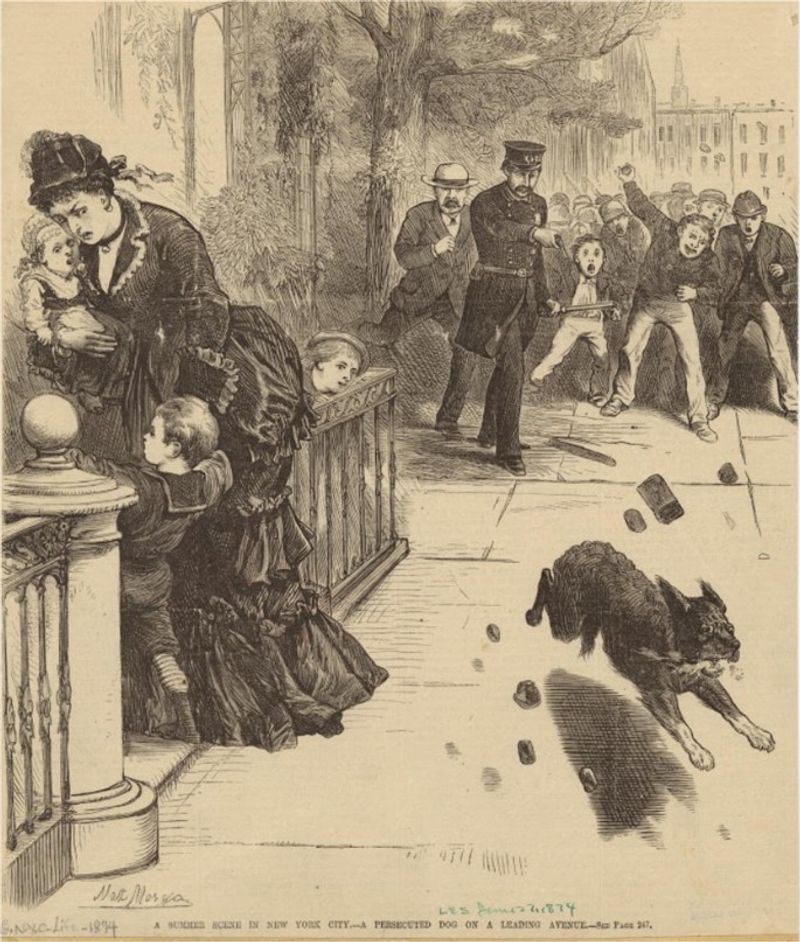

2. Black Cat Crossings

When a black cat crossed your path in 1800s America, panic often followed. Rural communities especially viewed these midnight-colored felines as witch companions or shape-shifted witches themselves, capable of cursing anyone they encountered.

Reactions varied regionally: Southerners might turn around and go home, abandoning their journey entirely. New Englanders sometimes threw salt over their left shoulder or made religious gestures to ward off evil. Midwesterners might spit on the ground or recite protective prayers.

Curiously, theater folk developed the opposite belief—they welcomed black cats backstage as good luck charms. Farmers sometimes valued black barn cats too, believing their presence protected grain stores from evil spirits that might cause crop failures.

3. Mirror-Breaking Dread

The sound of shattering glass struck terror into Victorian hearts. Breaking a mirror meant seven years of misfortune—a timeframe derived from ancient Roman beliefs about the soul renewing itself every seven years.

Americans of the 1800s took this superstition extremely seriously. When accidents happened, elaborate countermeasures followed: grinding mirror fragments to dust (eliminating their power), burying pieces under moonlight, or touching the shards to a tombstone at midnight. Wealthy families sometimes hired specialized “mirror doctors” to perform these rituals.

Mirrors were expensive luxuries then, making their breakage economically unfortunate as well. Some families kept broken mirrors in attics rather than disposing of them, fearing additional bad luck if the fragments were mishandled.

4. Knocking on Wood

The familiar tap-tap-tap on wooden surfaces wasn’t just a casual habit but a serious spiritual practice in 19th century America. Rooted in ancient pagan beliefs about forest spirits dwelling in trees, this gesture served as a direct communication with the supernatural world.

Americans knocked three times—once for the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—whenever they mentioned good fortune or future plans. Failing to perform this ritual after expressing hope was thought to invite disaster as punishment for pride.

Furniture craftsmen sometimes incorporated special knocking spots into their designs. Farm families selected specific “lucky trees” on their property designated for important knocks before major decisions, harvests, or journeys. The wood itself mattered—oak was considered most powerful.

5. Lucky Penny Findings

“Find a penny, pick it up, all day long you’ll have good luck.” This rhyme became a guiding principle during the 1800s when a single penny held significant purchasing power. The superstition likely evolved from older beliefs about pins bringing luck to their finders.

Pennies found face-up were considered particularly fortunate, believed to be deliberately placed by guardian angels. Many Americans carried their first-found penny as a permanent talisman, sometimes drilling holes to wear them as necklaces or sewing them into clothing hems.

Children were taught to spit on found pennies before pocketing them to “activate” the luck. Some families maintained special jars for lucky pennies, using them only for important purchases like seeds for planting or medicine during illness.

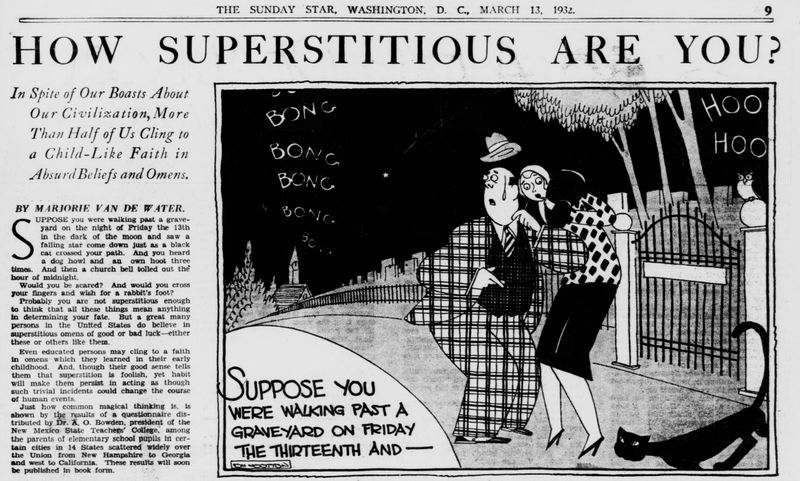

6. Friday the 13th Panic

The mere mention of Friday the 13th sent shivers down 1800s American spines. This dreaded date combined two already ominous elements: Friday (the day of Christ’s crucifixion) and the number 13 (recalling Judas as the 13th guest at the Last Supper).

By the late 19th century, this superstition had taken firm hold in American culture. Some trace its mainstream popularity to the 1880s secret society called the Thirteen Club, which deliberately mocked the superstition by dining together on Friday the 13th.

Businesses suffered on these dates as people avoided major decisions, travel, or celebrations. Many refused to start journeys, sign contracts, or even leave their homes until the cursed day had passed.

7. Rosemary as Theft Protection

Long before modern security systems, 19th century Americans planted rosemary around their homes as spiritual burglar protection. This aromatic herb served as the Victorian version of a home security system, believed to repel thieves through both mystical and practical means.

The superstition claimed that rosemary plants absorbed negative intentions, causing potential wrongdoers to suddenly forget their criminal plans when approaching a protected property. Some believed the plant would actually whisper warnings to homeowners when danger approached.

Beyond its supernatural qualities, rosemary’s strong scent did mask valuable food odors and its prickly nature deterred casual trespassers. Homeowners typically planted it beneath windows and near doors, often accompanied by specific blessing rituals to “activate” its protective powers.

8. Journey Return Taboo

Forgotten your handkerchief? Too bad—returning home after beginning a journey meant certain disaster for 19th century travelers. This superstition held such power that Americans would rather continue without essential items than risk the curse of turning back.

Gabriel Nostradamus’s popular 1899 book of superstitions specifically warned that reversing course after starting a trip would “spell disaster.” Those forced to return home would perform elaborate countermeasures: sitting in their original chair for five minutes before leaving again, exiting through a different door, or marking an X on the threshold.

Stagecoach drivers refused to turn back for forgotten passengers. Sailors wouldn’t return to port even for critical supplies if they’d already left the harbor. This belief was so ingrained that train stations kept shops selling essentials for travelers who refused to go home.

9. Upward Stumbles Bring Fortune

Tripping while climbing stairs wasn’t just embarrassing—it was a promising omen in 19th century America. This peculiar belief held that stumbling upward predicted imminent good fortune, while tripping downstairs foretold disaster.

When someone stumbled upward, witnesses would call out congratulations on their coming good luck. The fortunate stumbler was expected to make a wish before reaching the top step to “claim” their blessing. Many deliberately avoided counting steps or looking at their feet afterward, fearing it would negate the lucky accident.

The superstition likely originated as a face-saving courtesy that evolved into genuine belief. Practical Americans appreciated this rare instance where clumsiness brought positive consequences. Wealthy homeowners sometimes kept one step slightly higher than others to “manufacture” lucky stumbles for important guests.

10. Indoor Umbrella Prohibition

The seemingly innocent act of opening an umbrella indoors sparked genuine fear among 19th century Americans. This taboo originated from practical concerns in cramped homes where open umbrellas could cause injuries or damage breakables, but evolved into supernatural dread.

Some believed it invited death into the household. Others traced the superstition to ancient Roman women whose homes collapsed after opening sun-shades indoors. The fear was so pronounced that umbrella salesmen developed special demonstration techniques to show their wares without fully opening them inside shops.

Accidentally opening an umbrella indoors required immediate countermeasures: closing it, taking it outside, reopening it, then bringing it back in closed. Children were strictly taught never to play with umbrellas inside, with the warning that each open-close cycle indoors meant another rainy day that month.

11. Hairy Arms Signal Wealth

Excessive body hair—typically considered undesirable—became a source of pride for some 19th century Americans who believed hairy arms and hands signaled future prosperity. This curious superstition likely originated as a way for particularly hirsute individuals to reframe their condition as fortunate rather than embarrassing.

The belief held specific rules: hair on the back of hands predicted inheritance, while forearm hair suggested earned wealth. The darker and thicker the hair, the greater the expected fortune. Some parents even examined their children’s arms to predict their financial futures.

Wealthy men sometimes rolled up sleeves to display particularly hairy forearms during business negotiations, suggesting their natural propensity for accumulating wealth. Women with unusually hairy arms might discreetly reveal them when seeking marriage proposals, hinting at their “lucky” nature without violating modesty standards.

12. Nighttime Nail-Cutting Ban

The mundane task of nail trimming became fraught with supernatural danger after sunset. 19th century Americans firmly believed cutting nails after dark invited misfortune, with variations specifying different outcomes depending on which day’s night you chose.

Monday night nail-cutting brought wealth, Tuesday brought gifts, but Sunday night guaranteed you’d do something evil that week. The superstition likely began from practical concerns about poor lighting causing injuries, but evolved into beliefs about night spirits being attracted to nail clippings.

Rural families were particularly strict about this rule, keeping special nail-cutting dishes near sunny windows for daytime trimming. Disposed clippings required careful handling—burning them brought poverty, burying them prevented toothaches, and throwing them away carelessly allowed witches to collect them for curses.

13. Whistling Weather Summoning

A cheerful whistle indoors could bring meteorological disaster according to 19th century Americans. This superstition originated with sailors who believed whistling aboard ships could “whistle up a storm” by offending sea spirits or challenging the wind itself.

As maritime beliefs spread inland, Americans adapted the superstition to mean indoor whistling might bring rain—particularly problematic before modern weather forecasting when sudden storms could ruin harvests. The belief held specific nuances: whistling with your back to the fire summoned rain, facing north brought snow, and whistling in mines risked cave-ins.

Children were hushed from whistling indoors, especially during planting or harvest seasons. Theater performers had their own version—whistling backstage supposedly led to poor attendance (bad “box office wind”). Many rural communities maintained designated outdoor “whistling spots” where the practice was considered safe.

14. Misfortune’s Rule of Three

“Bad luck comes in threes” wasn’t just a saying but a dreaded certainty for 19th century Americans. After experiencing two unfortunate events, people would anxiously await the third, often interpreting ordinary occurrences as fulfillment of the pattern.

This superstition affected daily decision-making, with many Americans becoming exceptionally cautious after two mishaps. Farmers might delay planting, travelers postpone journeys, and businesses avoid new ventures until the third misfortune arrived and cleared the way for better luck.

Some tried to “cheat” the system by manufacturing a minor third misfortune—deliberately breaking something inexpensive or performing a small task poorly. Protective rituals included sleeping with scissors under the pillow (to “cut” the connection between misfortunes) or wearing clothes inside-out until the third event occurred.

15. Blessing Gifts for Children

First-time visitors to homes with new babies arrived bearing very specific gifts in 19th century America. Cake symbolized sweet life, salt represented preservation and purification, while eggs signified fertility and rebirth—each carefully selected to influence the child’s future.

These weren’t mere presents but spiritual investments in the child’s destiny. Visitors performed specific rituals while presenting their gifts: salt was sprinkled in a circle around the infant’s cradle, cake was broken (never cut) over the baby’s head, and eggs were rolled from head to toe while reciting blessings.

Raw eggs were discouraged for practical reasons, but hard-boiled ones adorned with symbols were popular. These gift rituals crossed social boundaries—even wealthy families welcomed salt from poor neighbors, believing humble offerings carried special protective power for children.

16. Peacock Feather Fears

The brilliant colors of peacock feathers concealed dark omens for 19th century Americans. Despite their beauty, these feathers were banished from homes—especially theaters, where their presence supposedly guaranteed production failures and accidents.

The superstition traced back to the “evil eye” pattern visible in the feather’s eye-like markings. Many believed these eyes were always watching, bringing misfortune to households. One famous incident involved an Australian theater manager who, upon discovering peacock designs in newly painted scenery, ordered the entire set repainted before opening night.

Even scientific-minded Americans often succumbed to this fear. Newspaper accounts from the period describe society hostesses removing guests’ peacock feather fans and hat decorations before allowing them entry. Farmers particularly avoided them, believing peacock feathers in the home would prevent hens from laying eggs.

17. Theatrical Good Luck Taboo

The phrase “good luck” triggered panic among 19th century American actors and theater workers. Directly wishing performers well was believed to tempt jealous spirits into sabotaging the production. Instead, the counter-intuitive “break a leg” became standard—suggesting something seemingly negative to fool lurking evil forces.

This theatrical superstition emerged from older performance traditions and spread throughout American theater communities by the mid-1800s. Actors developed elaborate pre-show rituals to protect themselves after hearing accidental good luck wishes: turning three times counterclockwise, touching a piece of the stage with their left hand, or whispering lines from Shakespeare’s tragedies.

Theater managers sometimes deliberately wished bad fortune on opening nights, hoping reverse psychology would appease supernatural forces. Production staff avoided mentioning specific disasters, fearing spoken fears might manifest during performances.

18. Squinting Women Warning

Encountering a squinting woman on the street sent 19th century American men scrambling for protective measures. This peculiar superstition held that passing such a woman without speaking directly to her guaranteed imminent misfortune.

The belief wasn’t merely casual—business deals were postponed, journeys delayed, and important decisions reconsidered after such encounters. The required countermeasure was specific: the affected person must address the woman directly before continuing their day. Any greeting would suffice, but avoiding eye contact during the interaction reportedly strengthened the protection.

This superstition likely originated from prejudices against people with physical differences, combined with ancient beliefs about the “evil eye.” Ironically, women with vision problems often found themselves approached by strangers offering unexpected greetings—never realizing they were perceived as potential harbingers of doom.

19. Ship Launching Ceremonies

Launching a new vessel without proper rituals spelled certain disaster for 19th century American sailors. These ceremonies weren’t mere celebrations but essential spiritual protection against the ocean’s dangers.

The tradition of breaking champagne bottles across bows began replacing earlier blood sacrifices in the late 1800s. Before this humanization, animal sacrifices (and in ancient times, human sacrifices) were considered necessary to appease water spirits. Sailors believed unnamed ships were invisible to sea gods and would refuse to board until christening ceremonies were complete.

Women were considered powerful figures in these rituals—a ship christened by a woman was believed to sail faster and survive storms better. However, superstition dictated that women who christened ships should never sail on them afterward, as the vessel would become jealous of its “mother” sharing attention with others aboard.

20. Evil Eye Protection

The malevolent power of an envious gaze terrified Americans across all social classes during the 1800s. This ancient belief in the “evil eye”—a glance capable of causing illness, misfortune, or death—shaped daily interactions and inspired countless protective measures.

Famous opera singer Adelina Patti exemplified how seriously this superstition was taken, refusing to perform if a cross-eyed conductor led the orchestra. Many Americans wore protective amulets—coral for children, garlic cloves for farmers, special blue beads for pregnant women. Homes featured strategic mirrors to reflect evil gazes back to their source.

The superstition created genuine social tensions. People with unusual eye colors or conditions faced suspicion and avoidance. Complimenting someone’s child without touching them afterward was considered dangerous—potentially signaling envy that could trigger the evil eye’s curse.

21. Bird-in-House Omens

A bird flying through an open window and into a home sent 19th century American families into immediate crisis mode. This event wasn’t just startling—it was interpreted as a death omen, specifically predicting that someone living in that house would die within the year.

Different bird species carried varying levels of doom. A robin suggested the death would be gentle, while blackbirds or crows foretold painful endings. White birds, especially doves, indicated a child’s death. The superstition was so firmly established that families sometimes temporarily moved out after such incidents.

Countermeasures included catching and releasing the bird through a different window or door than it entered, burning a lock of hair from each family member, or having a priest or minister bless the house. Some communities brought in “bird charmers” who claimed to be able to redirect the death omen to livestock instead.