Throughout the Middle Ages, knights weren’t always the noble heroes of storybooks. Some were feared warriors who left trails of blood and terror across Europe. These armored fighters used brutal tactics that shocked even their contemporaries. From serial killers hiding behind noble titles to military leaders who burned entire towns, these knights represent the darkest side of chivalry.

1. Gilles de Rais (1404–1440)

Once a respected French nobleman who fought alongside Joan of Arc, Gilles de Rais harbored horrifying secrets behind castle walls. His descent into madness began after Joan’s execution, when he abandoned military pursuits for occult experiments.

Local children began disappearing near his estates, with estimates of victims ranging from 80 to 600. His servants later testified about witnessing unspeakable tortures and rituals.

Eventually captured and tried, de Rais confessed to his crimes before being hanged and burned. His shocking transformation from decorated knight to history’s first documented serial killer makes him perhaps medieval Europe’s most disturbing figure.

2. Vlad the Impaler (Vlad III Dracula, 1431–1476)

The real-life inspiration behind Bram Stoker’s Dracula earned his gruesome nickname through unprecedented cruelty. As ruler of Wallachia (modern Romania), Vlad employed impalement as his signature method of execution—driving stakes through victims’ bodies and leaving them to die slowly over days.

During one campaign against Ottoman invaders, he created a “forest” of 20,000 impaled corpses outside his capital. The sight reportedly caused the Sultan’s army to retreat in horror.

Despite his brutality, many Romanians view Vlad as a folk hero who defended Christian Europe against Ottoman expansion. His methods, however, remain among history’s most stomach-turning examples of psychological warfare.

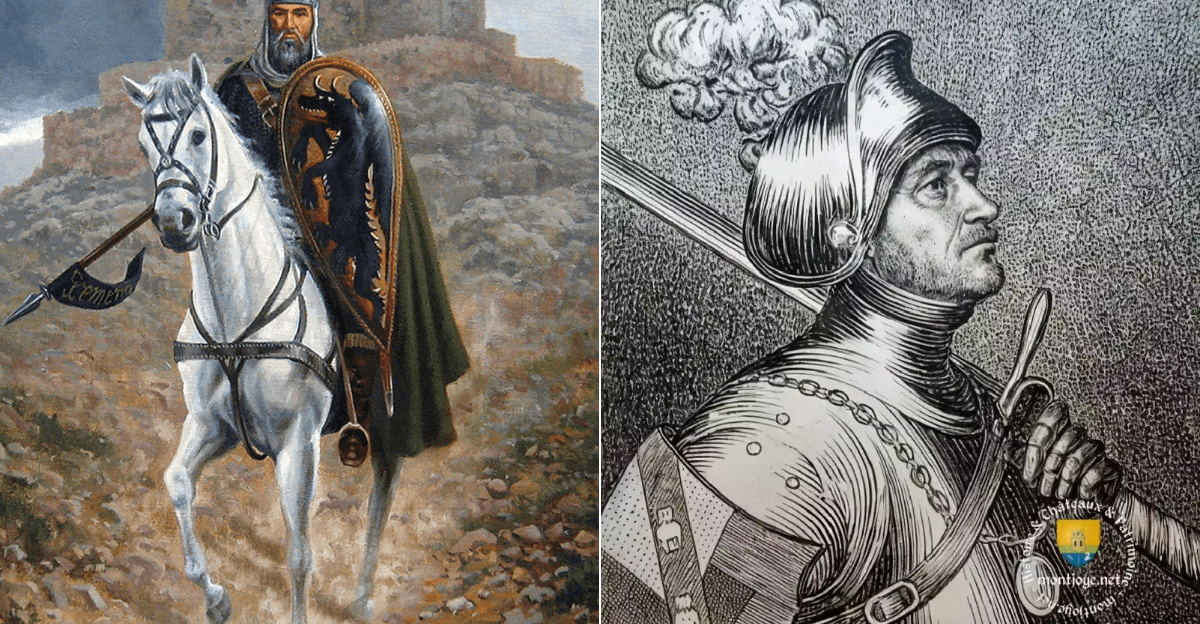

3. Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar (El Cid, 1043–1099)

Known as “El Cid” (from Arabic for “lord”), Rodrigo fought for both Christian and Muslim rulers in medieval Spain, showing loyalty only to whoever paid best. His battlefield prowess became legendary, but so did his collection of enemy heads.

After victories, El Cid ordered decapitations of high-ranking enemies, displaying their heads as trophies. Contemporary accounts describe him riding with bloody sacks containing heads of fallen Muslim commanders.

Modern Spain romanticizes him as a national hero, but historical records reveal a mercenary who switched sides repeatedly and employed terror tactics. His final achievement—capturing Valencia—involved a brutal siege that starved the city’s inhabitants before his forces stormed the walls.

4. William Marshal (1147–1219)

History remembers Marshal as “the greatest knight who ever lived,” serving five English kings and eventually becoming regent. Behind this sterling reputation lurked a tournament fighter of unmatched ferocity who claimed to have defeated over 500 knights in a single season.

Marshal pioneered brutal techniques like targeting horses rather than riders—considered dishonorable but devastatingly effective. He amassed fortune and lands through ransoming captured opponents.

During rebellions against King John, he ordered mass hangings of captured knights rather than accepting ransoms. His battlefield efficiency made him both respected and feared across Europe, proving that history’s “greatest knight” earned his reputation through ruthlessness as much as skill.

5. Jean de Metz (fl. 15th century)

A shadowy figure in Joan of Arc’s inner circle, Jean de Metz initially gained fame by escorting the future saint to meet the French king. His battlefield reputation, however, stemmed from cold pragmatism rather than divine inspiration.

Chronicles describe how de Metz routinely ordered the execution of prisoners who might slow his company’s advance. During the Loire campaign, he reportedly had dozens of English captives killed rather than arranging ransoms.

Unlike many of Joan’s companions who claimed religious motivation, de Metz approached warfare as brutal business. After Joan’s capture, he vanished from historical records—possibly continuing his mercenary career elsewhere or meeting a violent end himself.

6. Robert the Bruce (1274–1329)

Scotland’s national hero began his career with an act of shocking violence—stabbing his rival John Comyn to death on consecrated ground in Greyfriars Church. This sacrilege earned him excommunication but cleared his path to the throne.

The Bruce employed scorched earth tactics against English forces, burning croplands and executing those who collaborated with occupiers. After his famous victory at Bannockburn, he ordered the slaughter of Welsh archers rather than accepting their surrender.

His guerrilla campaigns featured midnight raids where sleeping English garrisons were put to the sword. While celebrated for Scottish independence, his methods would qualify as war crimes by modern standards—brutal even for his own violent era.

7. Tancred of Hauteville (1075–1112)

A Norman prince who joined the First Crusade, Tancred gained infamy during the siege of Jerusalem in 1099. After promising safe passage to Muslim civilians who sought refuge in the Al-Aqsa Mosque, he placed his banner over the building as protection.

Hours later, Tancred allowed his men to enter anyway, resulting in a massacre where thousands were slaughtered. Eyewitnesses described blood reaching their ankles inside the holy site.

After establishing himself as Prince of Galilee, Tancred continued campaigns of terror against Muslim villages, using torture to extract wealth from local populations. His betrayal at Al-Aqsa remains one of the Crusades’ most notorious atrocities, tainting his reputation despite his battlefield accomplishments.

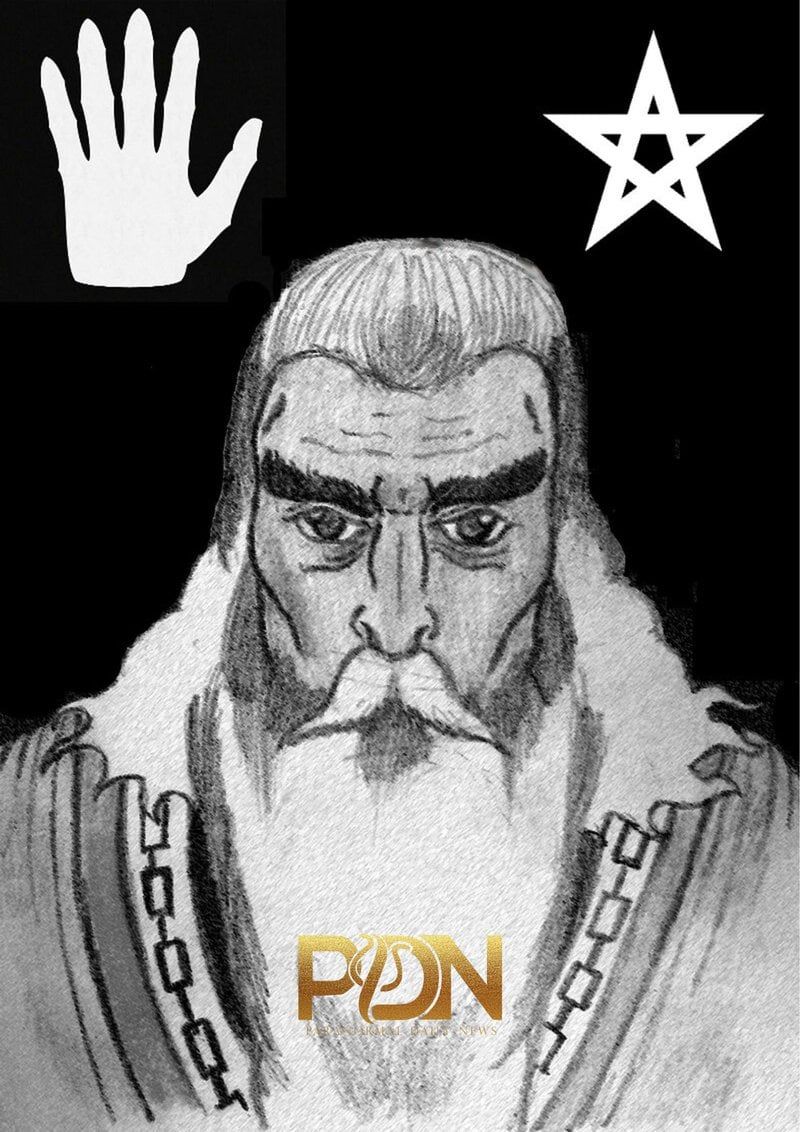

8. Jacques de Molay (1243–1314)

The last Grand Master of the Knights Templar led an organization that combined banking, military power, and religious authority. Before his own fiery execution, de Molay oversaw the Templars’ ruthless persecution of perceived heretics.

Under his leadership, Templar interrogators pioneered torture techniques to extract confessions from accused heretics. These methods included strappado (hanging by dislocated arms) and water torture—techniques later adopted by the Inquisition.

Ironically, de Molay himself would face these same tortures when King Philip IV turned against the Templars. After seven years of imprisonment and torture, he was burned at the stake in Paris, allegedly cursing the king and pope who condemned him to die within a year—a prophecy that came true.

9. Fulk Nerra (972–1040)

Known as “The Black Falcon,” this Count of Anjou built his reputation on calculated terror. After capturing the fortress of Saumur, Fulk had the wooden structures rebuilt with the bones of slain defenders mixed into the mortar—a literal foundation of enemies’ remains.

His preferred method of execution involved burning captives alive, sometimes while forcing their families to watch. Contemporary chronicles describe him ordering the construction of specialized cages to suspend victims over flames.

Strangely, Fulk also undertook four pilgrimages to Jerusalem seeking forgiveness for his crimes. Each time he returned to France, he resumed his brutal campaigns with renewed vigor, apparently believing his pilgrimages had wiped his moral slate clean.

10. Edward the Black Prince (1330–1376)

The eldest son of England’s Edward III earned his dark nickname through brutal campaigns across France. His specialty was the chevauchée—systematic devastation of civilian areas to destroy enemy resources and morale.

Edward’s forces burned thousands of villages, poisoned wells, and slaughtered livestock. His darkest hour came at Limoges in 1370, where he ordered the massacre of 3,000 civilians after the city surrendered, reportedly watching impassively as women and children were cut down.

Despite these atrocities, Edward was celebrated in England as the perfect chivalric knight. His tomb in Canterbury Cathedral became a pilgrimage site, demonstrating how easily medieval society overlooked brutality when directed at foreign enemies.

11. Bertrand du Guesclin (1320–1380)

France’s greatest knight during the Hundred Years’ War was nicknamed “The Eagle of Brittany” for his swift, devastating attacks. Born ugly and ill-tempered, du Guesclin transformed these disadvantages into a fearsome battlefield persona.

He pioneered psychological warfare, sending agents ahead to spread rumors of his army’s size and cruelty. His troops systematically destroyed wells, crops, and food stores to create famine zones around English territories.

After capturing towns, du Guesclin often allowed limited looting time for his men—a practice that resulted in widespread rape and murder despite his supposed “control.” His guerrilla tactics eventually drove the English from much of France, but left a devastated countryside and starving population in his wake.

12. John Hawkwood (1320–1394)

An English knight who became Italy’s most feared mercenary, Hawkwood commanded the infamous White Company—a band of professional killers who sold their swords to the highest bidder. City-states paid enormous sums not to fight him but simply to go elsewhere.

His business model centered on what we’d now call protection rackets. Towns that couldn’t afford his services faced systematic destruction, with Hawkwood’s men executing civic leaders and assaulting women in public squares to demonstrate the cost of resistance.

Florence eventually solved their Hawkwood problem by hiring him permanently. He died wealthy and honored with a cathedral funeral, proving that medieval Italy could forgive any atrocity if the perpetrator eventually switched to their side.

13. Don Pero Niño (1378–1453)

This Spanish knight earned the title “The Cruel” through raids along the English and North African coasts. His personal chronicle, The Unconquered Knight, boasts of atrocities modern readers find horrifying but which Niño considered achievements.

During one expedition, he ordered coastal villages burned with inhabitants locked inside buildings. Women captured during raids were distributed among his men as “rewards.” His ships became notorious for their red sails, which signaled no quarter would be given.

Unlike many ruthless knights who acted from necessity, Niño’s cruelty seemed performative—designed to enhance his reputation. His autobiography reveals a man who genuinely believed brutality was admirable, offering a disturbing glimpse into medieval notions of heroism.

14. Godfrey of Bouillon (1060–1100)

Elected the first ruler of Jerusalem after the First Crusade, Godfrey cultivated an image of piety that masked extraordinary brutality. His forces breached Jerusalem’s walls in July 1099, unleashing what chroniclers called “a bloodbath like no other.”

Godfrey personally led attacks on the Temple Mount where Jewish residents had sought sanctuary. Contemporary accounts describe crusaders wading through blood reaching their knees as they systematically executed every non-Christian they found.

After the massacre, Godfrey refused the title “King” of Jerusalem, preferring “Defender of the Holy Sepulchre”—a pious gesture that contrasted sharply with his blood-soaked conquest. His brief rule established the Kingdom of Jerusalem through a foundation of religious violence that would characterize the next two centuries.

15. Sir William Wallace (1270–1305)

Hollywood portrayed him as a freedom fighter, but historical Wallace employed terror tactics that shocked even his contemporaries. Before becoming Scotland’s resistance leader, he reportedly skinned an English sheriff alive and wore the skin as a sword belt.

Wallace’s strategy involved making occupation unbearable through targeted brutality. English tax collectors found in Scottish territory faced public disembowelment. His victory at Stirling Bridge was followed by using strips of English commander Hugh Cressingham’s skin as souvenirs for his officers.

Even Wallace’s execution—being hanged, drawn, and quartered—reflected how seriously England viewed his threat. While modern Scotland celebrates him as a national hero, contemporary accounts from both sides describe a man who understood that psychological warfare required spectacular cruelty.

16. Sir John Chandos (1320–1369)

One of England’s most celebrated knights, Chandos built his reputation on battlefield victories that often involved breaking the chivalric code he publicly championed. His most notorious action came during a supposed truce with French forces near Lussac.

After negotiating a temporary peace, Chandos secretly positioned archers in the woods. When French knights arrived for further talks, his hidden forces unleashed volleys of arrows before charging the survivors. Dozens of French nobles died in what they considered an ambush during a truce.

Edward III rewarded this duplicity by making Chandos a founding Knight of the Garter—England’s highest chivalric order. His career demonstrates how medieval warfare often honored chivalry in public while rewarding its violation in practice.

17. Sir James Douglas (1286–1330)

Known to the English as “The Black Douglas,” this Scottish knight specialized in psychological warfare that gave children nightmares for generations. His signature tactic was the night raid, entering occupied castles through sewage outlets or scaling walls during storms.

Once inside, Douglas would burn sleeping English soldiers in their beds or slit their throats. After one successful raid, he piled the bodies of the garrison in the castle’s cellar, then added food supplies on top before setting everything ablaze—creating what became known as a “Douglas Larder.”

English mothers would quiet unruly children with the threat, “The Black Douglas will get you!” His shadow campaigns eventually made the English-Scottish border region ungovernable through sheer terror.

18. Sir Thomas Malory (1415–1471)

The author who gave us King Arthur’s noble tales led a life that contradicted everything he wrote about chivalry. Court records show Malory was jailed multiple times for violent crimes, including armed robbery, attempted murder, and rape.

His most notorious incident involved ambushing the Duke of Buckingham on a country road, then extorting protection money from local villages by threatening similar attacks. During one imprisonment, he escaped by swimming a castle moat, then allegedly returned to rape his jailer’s wife.

Malory wrote Le Morte d’Arthur while imprisoned in Newgate for his crimes. The irony remains striking—the man who defined our romantic vision of knights was himself a criminal knight who embodied the opposite of Arthurian values.

19. Sir William de Soules (d. 1320)

A Scottish border lord whose cruelty became legendary, de Soules combined political treachery with what locals believed was actual witchcraft. After plotting against Robert the Bruce, he retreated to his castle where rumors spread about children disappearing from nearby villages.

Local folklore claimed de Soules practiced black magic requiring child sacrifices. While these specific accusations remain unproven, historical records confirm his execution for treason—by being boiled alive in a lead cauldron at Ninestane Rig.

Archaeological excavations at his castle uncovered unusual remains in the foundations, fueling speculation about human sacrifices. Whether genuine sorcerer or just exceptionally cruel, de Soules’ memory survived in Scottish border ballads warning children away from forests near his former lands.

20. Sir John Fastolf (1380–1459)

Shakespeare transformed him into the comic Falstaff, but the real Fastolf was anything but funny to French villagers. As military governor of conquered territories in France, he implemented a systematic terror campaign against civilian populations.

Fastolf ordered summary executions of French peasants suspected of aiding resistance fighters. Villages that failed to meet impossible supply quotas saw their leaders publicly tortured. His troops were permitted to commit atrocities with impunity—a policy designed to crush French morale.

After being accused of cowardice at the Battle of Patay, Fastolf became even more brutal toward civilians, perhaps compensating for his damaged reputation. His name became so notorious in northern France that mothers threatened misbehaving children with “Fastolf will come for you.”