Sometimes the people who change the world aren’t planning to do it at all. History is full of regular folks who, through luck, timing, or pure accident, ended up reshaping how we live today. They weren’t kings or presidents – just everyday people going about their lives when something extraordinary happened. Their unplanned contributions have changed medicine, technology, and even how we understand what it means to be human.

1. Mary Anning (1799–1847)

Daughter of a poor cabinet maker, Mary never received formal education but possessed an extraordinary eye for fossil hunting. Walking along Dorset’s rugged coastline after storms, she could spot treasures others missed completely. Her discovery of the first complete ichthyosaur at just 12 years old stunned the scientific community. Male scientists often took credit for her finds, yet she persisted. Without knowing it, this working-class girl with a hammer and determination helped establish paleontology as a scientific discipline, forcing scholars to reconsider biblical timelines of Earth’s age and proving extinction was real.

2. Alexander Fleming (1881–1955)

Messy lab habits changed medicine forever. Fleming, a Scottish bacteriologist, returned from vacation in September 1928 to find something peculiar among his disorganized petri dishes – a mold contamination surrounded by a bacteria-free zone. Rather than discarding the “ruined” experiment, his curiosity led him to investigate. The mold, Penicillium notatum, was producing a substance that killed dangerous bacteria. Fleming’s accidental discovery of penicillin eventually saved millions of lives. Before antibiotics, even minor infections could be death sentences. His moment of scientific serendipity transformed modern medicine and earned him a Nobel Prize.

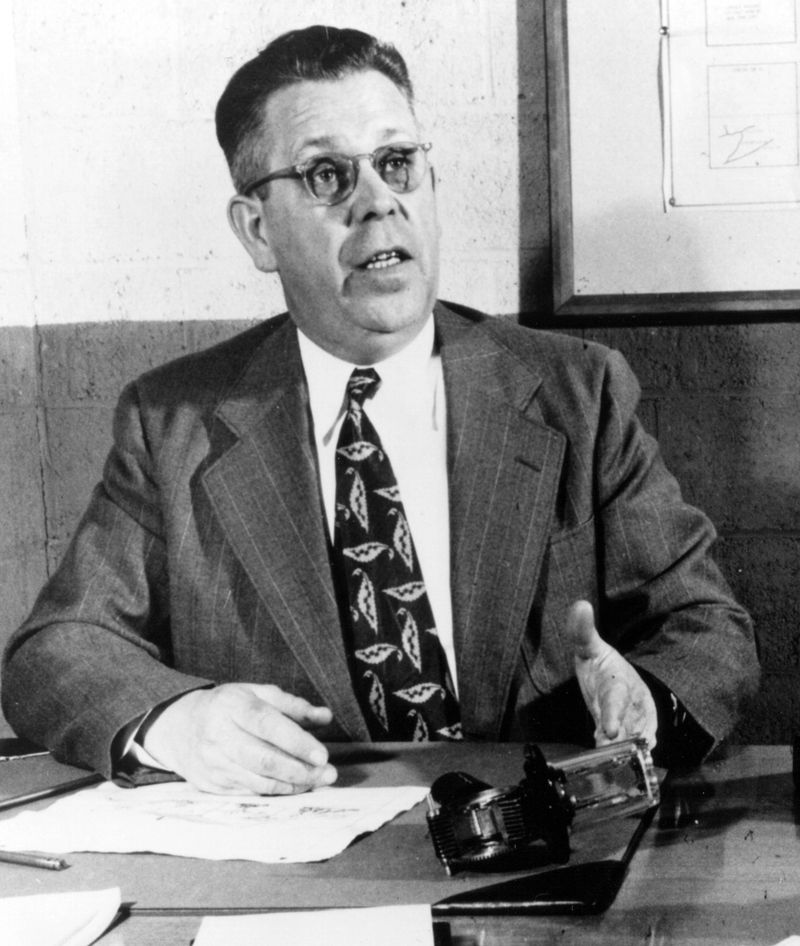

3. Percy Spencer (1894–1970)

A self-educated engineer with only a fifth-grade education, Spencer stood near a magnetron during a radar experiment at Raytheon and noticed something odd. The chocolate bar in his pocket had completely melted, though he felt no heat. Intrigued rather than annoyed, Spencer immediately began testing other foods. Popcorn kernels exploded. An egg cooked so rapidly it blew up in a colleague’s face. His curious investigation led to the first microwave oven – originally called the “Radarange” – a massive 750-pound device. Today’s compact kitchen essential exists because one man paid attention to a ruined snack.

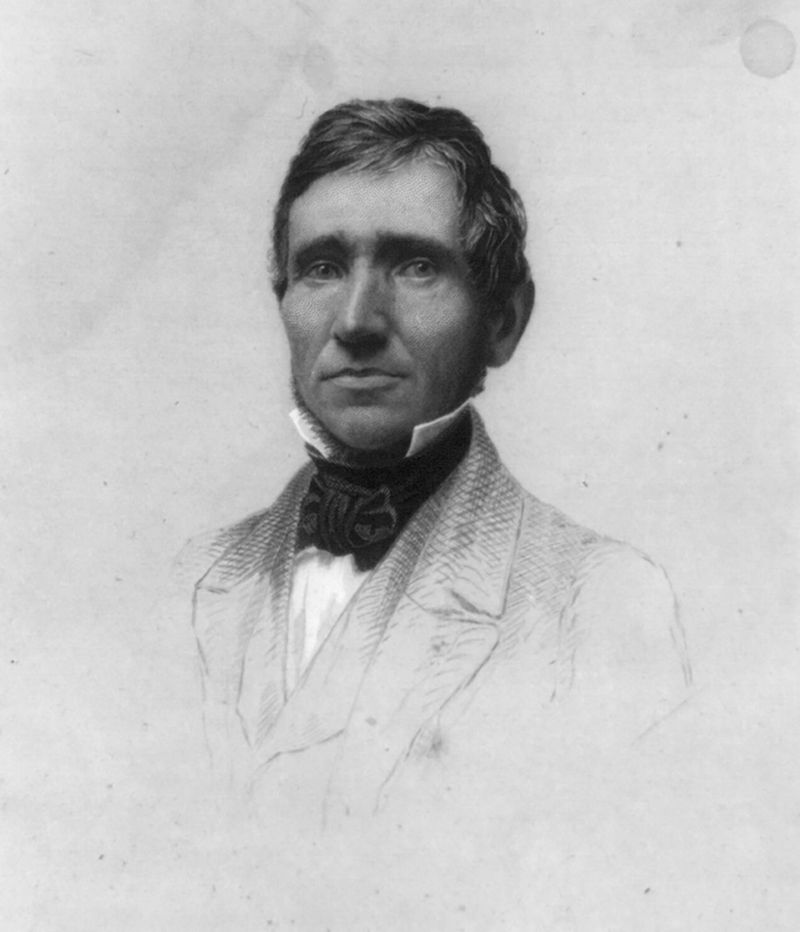

4. Charles Goodyear (1800–1860)

Obsession drove Goodyear to the brink of madness. For years, he experimented with rubber – a promising material that unfortunately melted in summer and cracked in winter. His quest bankrupted his family, landing him in debtors’ prison multiple times. The breakthrough came through pure accident in 1839. While demonstrating a rubber mixture at a general store, he spilled his concoction onto a hot stove. Instead of melting, it charred like leather, creating a weatherproof material. Goodyear had discovered vulcanization, revolutionizing manufacturing. Ironically, he died $200,000 in debt while companies made fortunes from his accident. The Goodyear tire company, named in his honor, wasn’t even his creation.

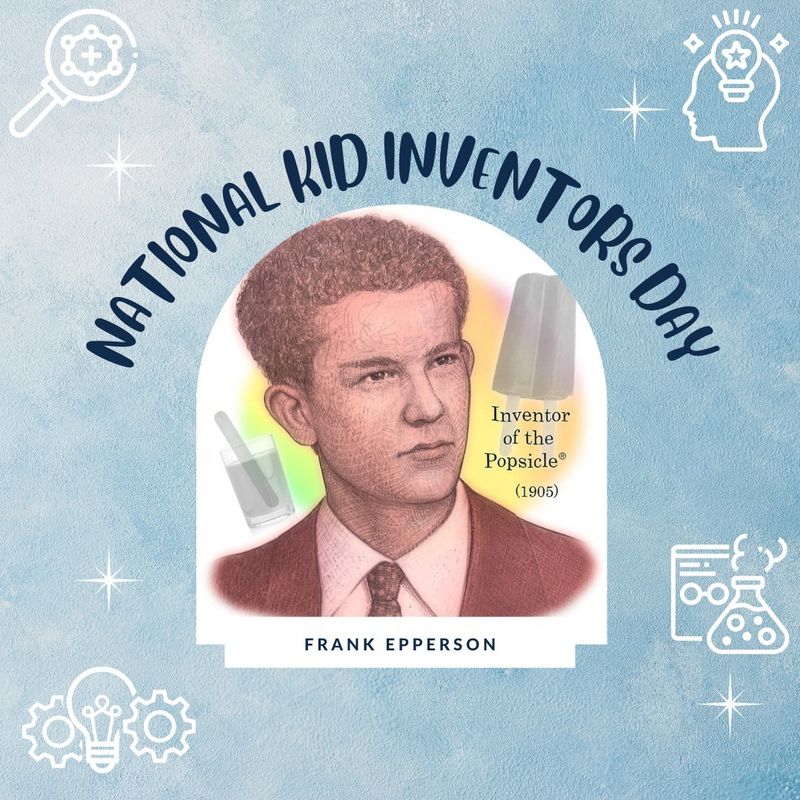

5. Frank Epperson (1883–1983)

Childhood accidents rarely create million-dollar industries. Eleven-year-old Frank left a cup of powdered soda mixed with water on his porch one freezing San Francisco night in 1905, stirring stick still inside. Morning revealed an icy treat on a convenient wooden handle. Young Frank dubbed his creation the “Epsicle” and initially kept it as a personal family treat. Eighteen years later, as a grown man with his own children, he finally patented his frozen novelty as the “Popsicle.” The accidental invention sold for $4,000 to the Joe Lowe Company. Today, over two billion Popsicles are consumed annually worldwide – all because a kid forgot to bring his drink inside.

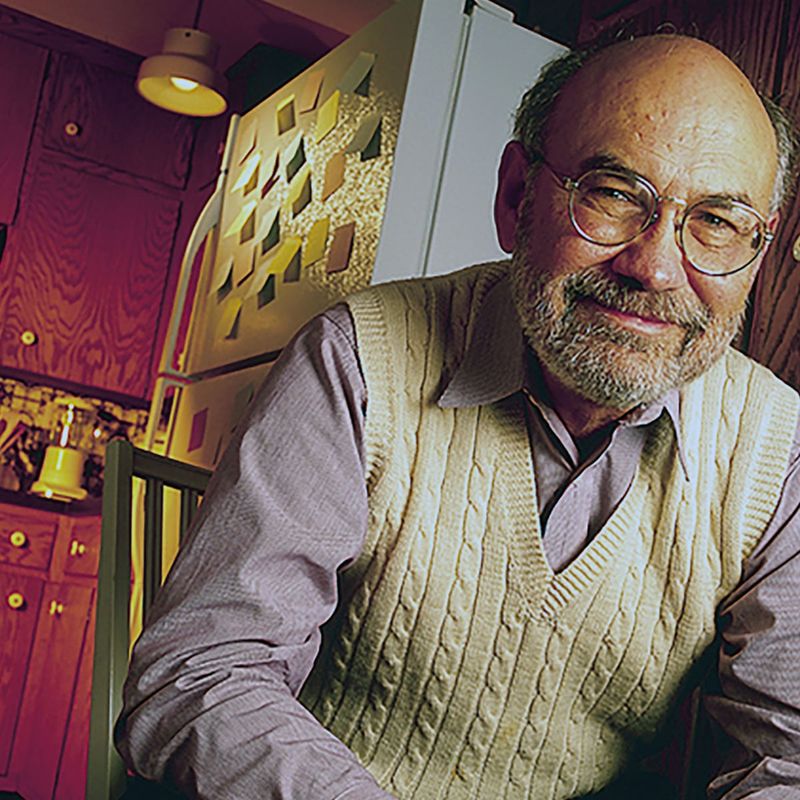

6. Spencer Silver (1941–2021)

Failure often precedes innovation. In 1968, chemist Spencer Silver attempted to create a super-strong adhesive for 3M’s aerospace division. Instead, he produced something bizarrely weak – a glue that stuck lightly to surfaces but could be peeled off without leaving residue. For five years, Silver promoted his “lousy” adhesive within 3M, finding no practical applications. The breakthrough came when colleague Art Fry, frustrated by paper bookmarks falling from his hymnal during choir practice, remembered Silver’s peculiar glue. Together they created the Post-it® Note, transforming office communication worldwide. Silver’s initially disappointing discovery now generates over $1 billion annually for 3M, proving some mistakes are worth making.

7. Karl Paul Link (1901–1978)

Mystery deaths plagued Wisconsin farmers in the 1920s. Their cattle were bleeding uncontrollably after eating sweet clover hay, and nobody understood why. Desperate farmers brought samples to biochemist Karl Paul Link at the University of Wisconsin. Link and his team discovered that moldy sweet clover contained a compound that prevented blood clotting. Rather than just solving the cattle mystery, Link recognized greater potential in this accidental finding. The compound – named warfarin after the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation – became first a powerful rat poison, then ironically, a life-saving blood thinner prescribed to millions of heart patients. President Eisenhower himself used it after his heart attack in 1955.

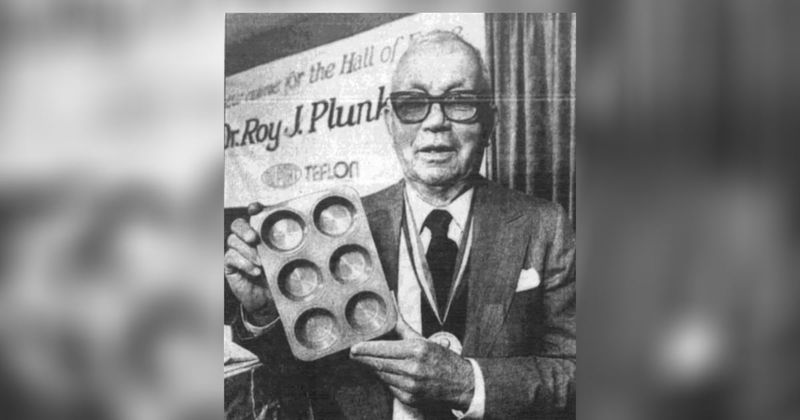

8. Roy Plunkett (1910–1994)

Refrigerant research led to an unexpected kitchen revolution. In 1938, 27-year-old chemist Roy Plunkett was developing new chlorofluorocarbon refrigerants at DuPont when he checked a stored gas cylinder that mysteriously stopped flowing. Puzzled, Plunkett sawed the cylinder open and discovered a slippery white powder coating the interior. The tetrafluoroethylene gas had somehow polymerized into a substance with remarkable properties – heat-resistant, chemically inert, and incredibly slick. This accident created polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), later branded as Teflon®. Initially used in military applications during WWII, it eventually revolutionized cookware in the 1960s. Plunkett’s curiosity about a failed experiment created a multi-billion-dollar industry.

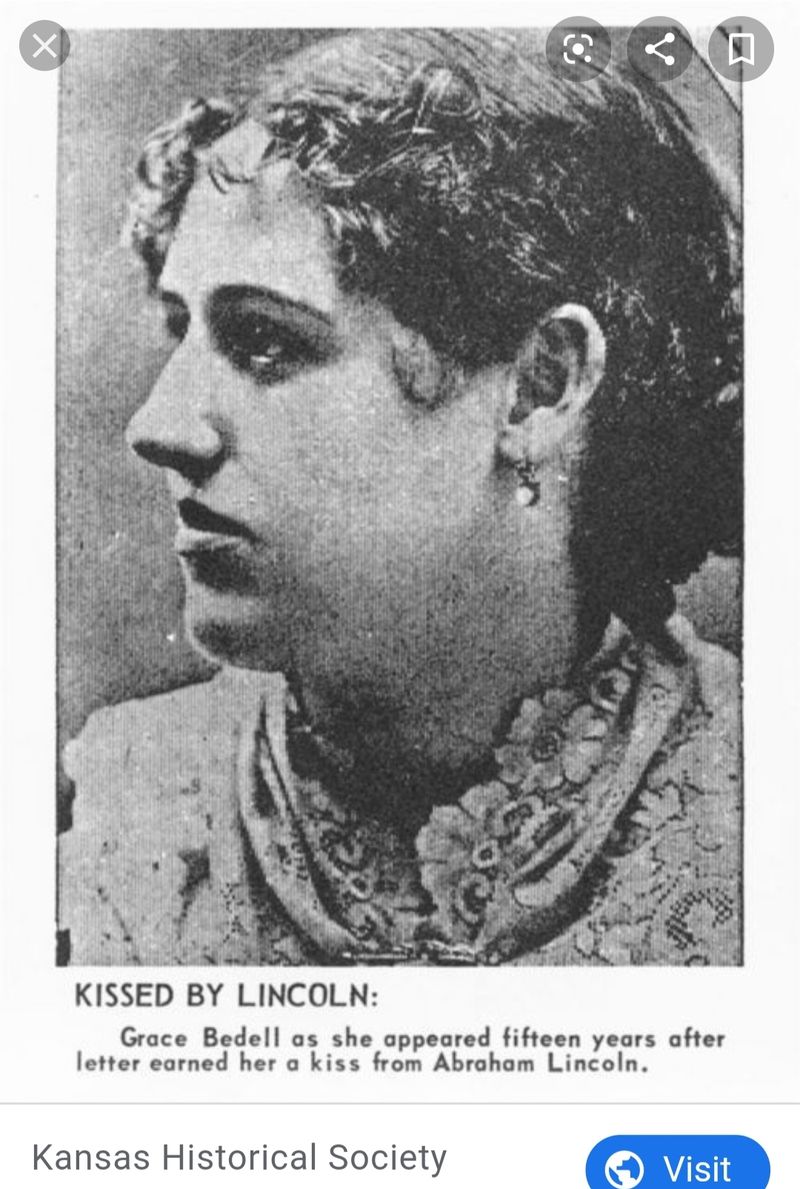

9. Grace Bedell (1848–1936)

Presidential image consultants existed long before television. In 1860, 11-year-old Grace Bedell wrote a candid letter to Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln suggesting he grow a beard: “All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you.” Surprisingly, Lincoln replied to the child and took her advice seriously. By his inauguration, his now-iconic beard was fully grown. When his train stopped in Westfield, New York during his journey to Washington, Lincoln specifically asked to meet Grace. This young girl’s suggestion permanently transformed Lincoln’s appearance into one of history’s most recognizable faces. Her simple letter may have helped soften his public image during America’s most divisive era.

10. George de Mestral (1907–1990)

Hunting trips should involve trophies, not textile breakthroughs. Swiss engineer George de Mestral returned from a 1941 Alpine hunting expedition covered in annoying burrs – those sticky seed pods that cling to clothing and fur. Instead of just brushing them off, de Mestral examined them under a microscope, discovering tiny hooks that caught on fabric loops. This natural fastening mechanism sparked an idea. Eight years of development created Velcro® (from velours and crochet – French for “velvet” and “hook”). Initially ridiculed, the fastener found its first major customer in NASA’s space program. Today, that hunting annoyance generates over $100 million annually and has applications from shoes to medical equipment.

11. Albert Hofmann (1906–2008)

Laboratory safety standards were different in 1943. Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann was researching ergot fungus derivatives when he accidentally absorbed a tiny amount of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD-25) through his fingertips. Feeling strangely restless, Hofmann left work early, experiencing what he described as “an uninterrupted stream of fantastic images of extraordinary plasticity… accompanied by an intense, kaleidoscope-like play of colors.” Three days later, he intentionally took a larger dose in the first planned LSD trip. His accidental exposure launched decades of research into psychedelics for treating mental disorders, sparked a counterculture revolution, and fundamentally changed how science understands consciousness and brain chemistry.

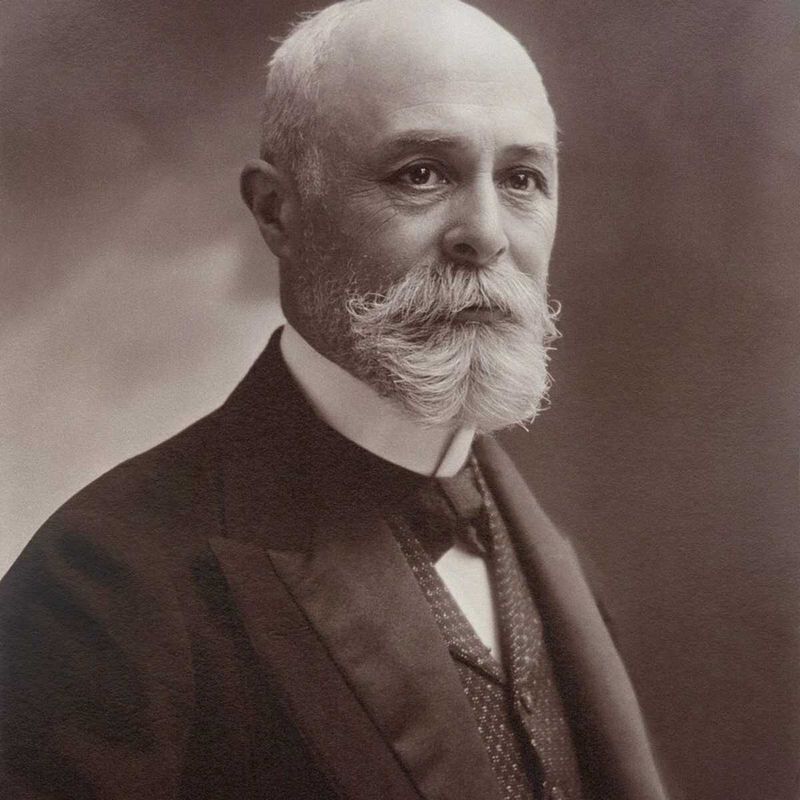

12. Henri Becquerel (1852–1908)

Cloudy weather led to a groundbreaking physics discovery. In 1896, physicist Henri Becquerel was investigating whether uranium salts produced X-rays when exposed to sunlight. His experiment required bright sun to work properly. During several overcast Paris days, Becquerel stored his unexposed photographic plates wrapped in black paper with uranium crystals on top in a drawer. Developing them later, he was shocked to find the plates were fogged despite never being exposed to sunlight. The uranium had emitted invisible rays without any energy input. This accidental discovery of radioactivity opened an entirely new field of physics, earned Becquerel a Nobel Prize, and eventually led to nuclear energy, radiation therapy, and atomic weapons.

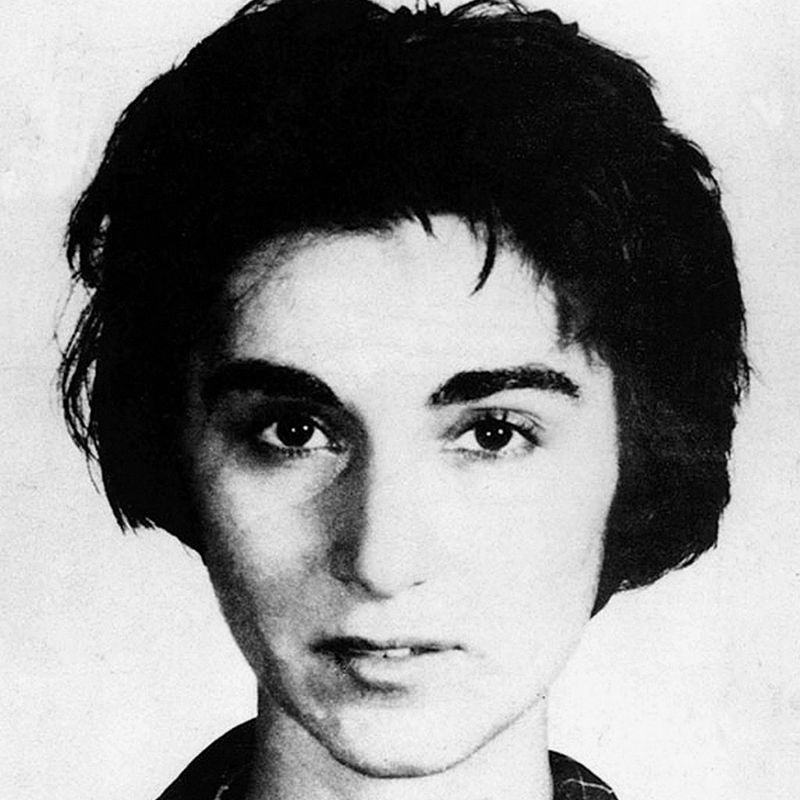

13. Kitty Genovese (1935–1964)

Her tragic death transformed psychology and emergency response systems. When 28-year-old Kitty Genovese was murdered outside her Queens apartment in 1964, initial reports claimed 38 witnesses watched or heard the attack but did nothing to help. While later investigations revealed this number was exaggerated, the case profoundly impacted social psychology. Researchers Darley and Latané conducted groundbreaking studies on the “bystander effect” – how individuals are less likely to help when others are present. Genovese’s murder also directly led to the development of the 911 emergency system in New York. Before her death, calling police meant finding the right precinct number, often causing deadly delays.

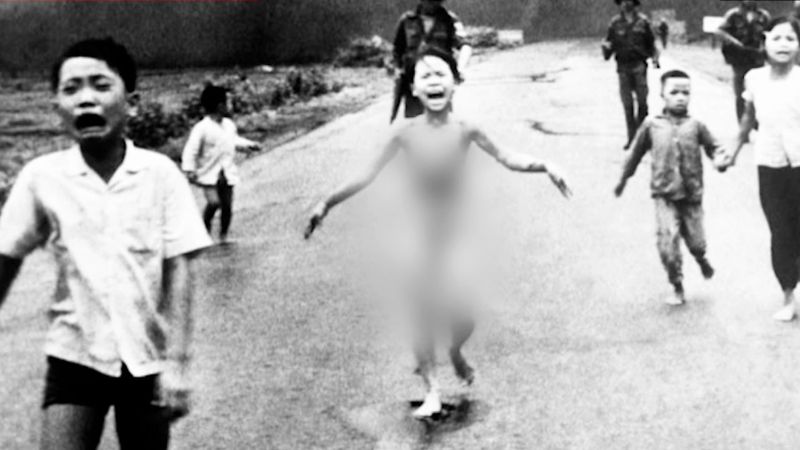

14. Phan Thị Kim Phúc (b. 1963)

One horrifying photograph changed the course of a war. On June 8, 1972, nine-year-old Kim Phúc ran screaming down a Vietnamese road, her clothes burned away by napalm, her skin on fire. AP photographer Nick Ut captured the moment. The image of this terrified child cut through political rhetoric about “necessary military action.” Published worldwide, it crystallized anti-war sentiment and became a defining symbol of the conflict’s human cost. Remarkably, Kim Phúc survived her burns. Ut took her to a hospital after taking the photo. Now a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador and peace activist, she transformed from accidental war icon to intentional advocate, her unplanned place in history giving her a powerful platform.

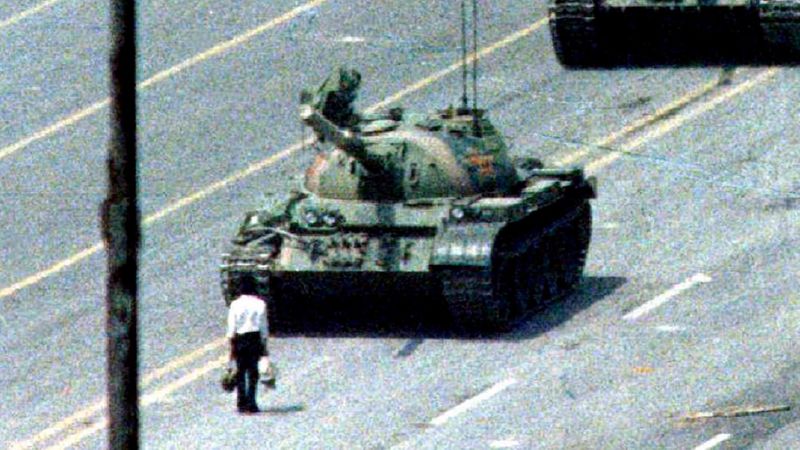

15. “Tank Man” of Tiananmen (unknown)

His name remains unknown, but his courage became universal. On June 5, 1989, a solitary Chinese man carrying shopping bags stepped in front of advancing tanks leaving Tiananmen Square after the government’s bloody crackdown on pro-democracy protesters. For several minutes, he blocked their path, even climbing onto one tank to speak with its driver. Then he disappeared into the crowd, his identity never confirmed despite global interest. This anonymous shopper’s spontaneous act of defiance, captured by foreign journalists from hotel balconies, became an enduring symbol of resistance against overwhelming power. TIME magazine later named the unknown man one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century.

16. Tsutomu Yamaguchi (1916–2010)

History’s most unlucky lucky man endured the unimaginable – twice. On August 6, 1945, Yamaguchi was in Hiroshima on a business trip when the first atomic bomb detonated just 3 kilometers away. Despite burns and radiation exposure, he managed to return home – to Nagasaki. Three days later, while explaining his Hiroshima experience to his disbelieving boss, the second atomic bomb exploded. Yamaguchi became the only person officially recognized by Japan as having survived both nuclear attacks. His extraordinary testimony about nuclear weapons’ human cost influenced post-war disarmament debates. After decades of silence, he became a vocal peace advocate in his final years, his accidental historical position giving unique moral authority.

17. Frank Whittle (1907–1996)

Rejected ideas sometimes change the world. As a young Royal Air Force cadet in 1928, Frank Whittle proposed a revolutionary aircraft engine using turbine technology. His superiors dismissed it as impractical fantasy. Undeterred, Whittle continued developing his “useless” idea in his spare time while serving as a test pilot. Working with minimal resources, he created the first viable jet engine prototype in 1937, despite having no official backing. World War II finally brought recognition to his invention. Commercial jet travel, now connecting our global society, exists because one stubborn pilot refused to abandon his side project. Whittle’s persistence transformed how humans traverse the planet.

18. Anne Frank’s Diary Keeper (Miep Gies, 1909–2010)

A secretary’s quick thinking preserved one of history’s most powerful voices. After Nazi police raided the Secret Annex on August 4, 1944, arresting the eight Jews hiding there, office worker Miep Gies returned to gather any valuables before the space was looted. Among scattered papers, she found Anne Frank’s diary and notebooks. Without reading them, Gies locked these writings away, hoping to return them to Anne after the war. When Otto Frank returned as the family’s sole survivor, Gies gave him his daughter’s diary. Its publication revealed Anne’s extraordinary voice and humanized Holocaust statistics for millions. One secretary’s split-second decision to salvage “just some papers” preserved history’s most famous teenage diary.

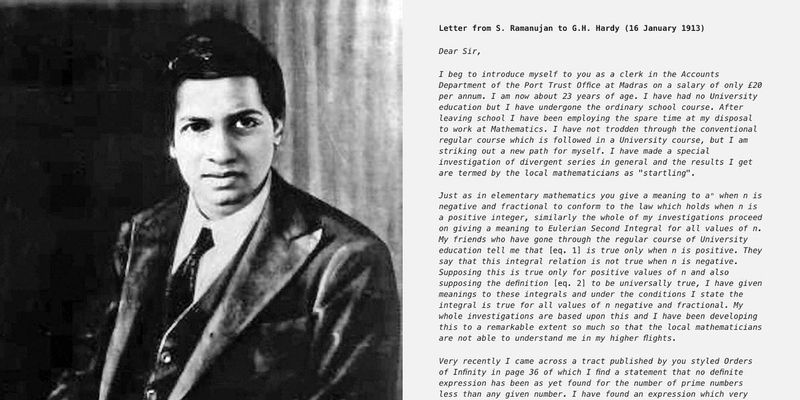

19. Srinivasa Ramanujan’s Postman (Madras Post Office clerk)

Mathematics changed because one postal worker did his job well. In 1913, a humble Indian clerk named Srinivasa Ramanujan mailed his strange mathematical formulas to professors at Cambridge University, hoping someone would recognize their value. Most recipients dismissed these unsolicited papers from an unknown, uneducated man in colonial India. But the letters reached mathematician G.H. Hardy because an anonymous postal clerk ensured proper delivery. Hardy immediately recognized Ramanujan’s extraordinary genius and arranged his journey to Cambridge. This unknown postal worker’s routine delivery connected two worlds, allowing a self-taught mathematical prodigy to revolutionize number theory. Sometimes history’s pivotal messengers remain nameless.

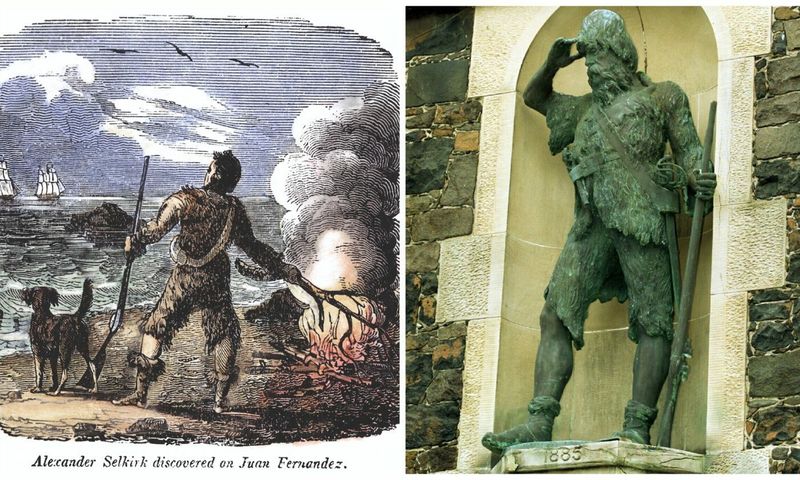

20. Alexander Selkirk (1676–1721)

Being marooned created literary history. Scottish sailor Alexander Selkirk argued with his captain about their ship’s seaworthiness during a 1704 privateering expedition. After demanding to be put ashore on an uninhabited Pacific island, Selkirk immediately regretted his decision as he watched the ship depart. For four years and four months, he survived alone, hunting goats, domesticating feral cats, and scanning the horizon for rescue. When finally discovered in 1709, he had become a skilled survivalist. Writer Daniel Defoe later based Robinson Crusoe on Selkirk’s ordeal, creating the first English novel and inventing the castaway genre. A sailor’s impulsive decision during an argument inadvertently shaped literary history.