The Great Depression, lasting from 1929 to the late 1930s, was one of America’s darkest economic periods. Families lost homes, farmers watched crops fail, and unemployment reached staggering heights. Talented photographers documented this suffering, creating powerful images that still resonate today. These 21 photos reveal the human toll of economic collapse and environmental disaster, telling stories that words alone cannot convey.

1. Migrant Mother

A worried face that became the human symbol of an American tragedy. Florence Owens Thompson, a 32-year-old mother of seven, sits with three of her children in a makeshift tent in Nipomo, California. Her anxious expression captures the uncertainty faced by thousands of migrant workers. Photographer Dorothea Lange discovered this family after they had sold their tent to buy food. The pea crop they had traveled to harvest had frozen, leaving them with nothing. Within days of this photo’s publication, the government sent aid to the camp. This single image did more to humanize the Depression than any statistic could, showing the resilience of a mother determined to keep her family alive despite impossible circumstances.

2. Dust Bowl Farmer

Against a sky darkened by swirling dust, a father and his two young sons walk hunched forward through a barren landscape. Their silhouettes tell a story of perseverance amid environmental catastrophe in Cimarron County, Oklahoma. Farming families like this one faced not just economic hardship but a natural disaster of biblical proportions. Years of drought combined with poor farming practices had turned America’s heartland into a wasteland where massive dust storms could block out the sun for days. Arthur Rothstein’s haunting image shows how these “black blizzards” became a daily battle for survival. Each step through the choking dust represented another day of fighting to keep their farm and way of life intact.

3. Breadline

Hundreds of men stand in a seemingly endless line, waiting for a single meal. Their faces show a mix of resignation and quiet dignity. Many wear suits and hats—reminders of better days before the economic collapse. By 1932, one in four Americans was unemployed. These breadlines became a common sight in cities across the nation, where formerly middle-class workers now depended on charity to feed their families. The contrast between the well-dressed men and their desperate circumstances speaks volumes. What makes this image particularly powerful is the orderliness of the line. Despite hunger and hopelessness, these men maintained their humanity and social order, waiting patiently for the small comfort of a free meal.

4. Dust Bowl Children

Two small boys stand side by side, their faces and clothes covered in a fine layer of dust. Their squinting eyes peer out from dirty faces with an unsettling maturity beyond their years. These children never knew a normal childhood. Born into the Dust Bowl era, they lived with constant hunger and the ever-present dust that found its way into food, beds, and lungs. Many children developed “dust pneumonia” from breathing the particles that infiltrated even sealed homes. Lange’s photograph forces viewers to confront the innocent victims of both economic and environmental disasters. While adults could somewhat understand the complex factors behind their suffering, these children simply endured a harsh reality they never chose or deserved.

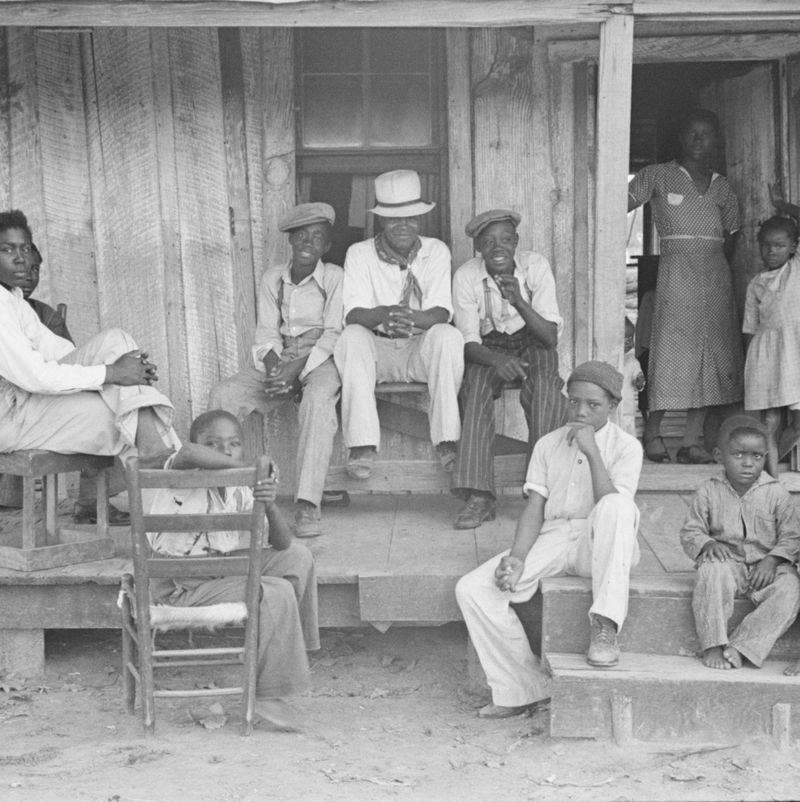

5. Sharecropper Family

Raw poverty stares back at us through the eyes of an Alabama tenant farming family. Standing in front of their bare wooden shack, their gaunt faces and threadbare clothes reveal generations of hardship made worse by the Depression. Walker Evans captured this family as part of his work with writer James Agee on their landmark book “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” The father’s weathered face shows years of backbreaking labor for minimal returns in a system that kept sharecroppers perpetually indebted to landowners. What makes this image unforgettable is the dignity these people maintain despite their circumstances. They stand tall, facing the camera directly, neither asking for pity nor hiding their reality—a visual testament to the resilience of America’s rural poor.

6. Homeless Man

Curled up on a city sidewalk, a man sleeps using newspapers as both mattress and blanket. Pedestrians walk past, their indifference suggesting how commonplace such sights had become in America’s cities. Before the Depression, homelessness at this scale was unimaginable. After the 1929 crash, countless formerly employed men found themselves without work, savings, or shelter. Many were veterans who had fought for their country only to find themselves abandoned by it. The newspapers covering this man create a bitter irony—the same pages reporting on the economic crisis were being used as his only protection against the elements. This anonymous photographer captured how urban homelessness had transformed from individual tragedy to mass phenomenon during the Depression years.

7. Farmer and Son

A father and his young boy lean into a howling dust storm, their bodies angled against the force of nature itself. The sky behind them has disappeared into an ominous dark cloud as they make their way to a wooden outbuilding. This photograph captures the daily reality for families in Oklahoma’s dust bowl region. What once was fertile farmland had become a desert-like wasteland where massive dust storms could appear suddenly, forcing farmers to battle not just poverty but an environment turned hostile. The protective posture of the father, shielding his son as best he can, speaks to the impossible choices parents faced. Many eventually abandoned generations-old family farms, joining the exodus of “Okies” heading west in search of work and cleaner air their children could safely breathe.

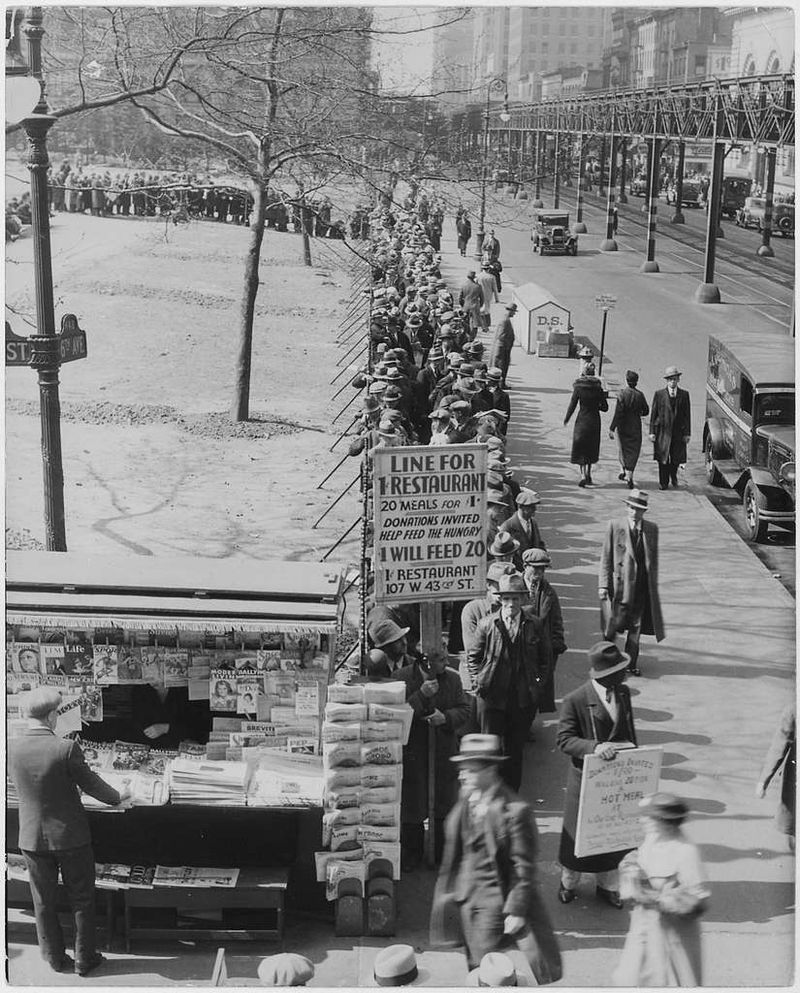

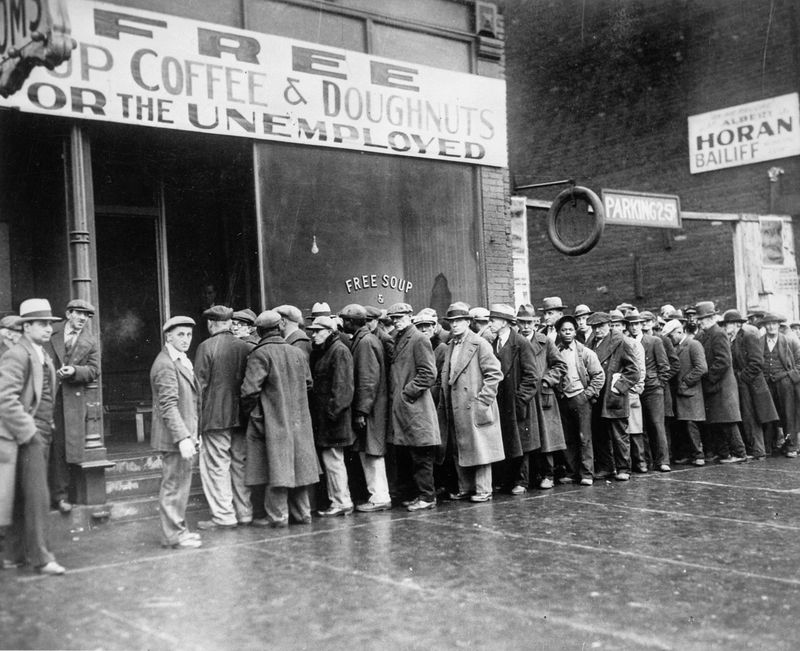

8. Soup Kitchen

Hunger writes itself across the faces of dozens of men standing in a Chicago soup kitchen line. Many wear coats and hats despite the warm weather—their only possessions they dare not leave behind. Soup kitchens became lifelines during the Depression, operated by charities and religious organizations when government assistance was minimal. For many men who had once been providers for their families, accepting charity marked a painful surrender of pride. The photographer captured not just physical hunger but the psychological toll of unemployment. These men’s expressions reveal the weight of shame and uncertainty about the future. By 1931, the initial shock of the economic collapse had given way to a grinding daily struggle for survival that would continue for years.

9. Migrant Family

A family of seven crowds around their packed car, preparing to leave behind everything they’ve known. Their weathered faces show both determination and uncertainty as they join thousands heading west on Route 66. These were the real-life counterparts to the Joad family in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.” Driven from their farms by dust storms and bank foreclosures, they followed rumors of agricultural work in California. The old jalopy contains their entire world—mattresses, cooking utensils, and children squeezed together. Lange’s photograph reveals both the desperation and the hope that fueled this migration. Despite having lost their land and livelihoods, these families maintained their bonds and belief in a better future somewhere down the road, even as that faith was repeatedly tested.

10. Bonus Army

Thousands of World War I veterans march through Washington D.C., demanding early payment of service bonuses promised for 1945. Their disciplined ranks speak to their military training, now employed in desperate protest. The Bonus Army’s story represents one of the darkest chapters of the Depression. After peaceful occupation of vacant buildings, these veterans and their families were violently evicted by Army troops led by General Douglas MacArthur, who used tanks, cavalry, and tear gas against fellow soldiers. This photograph was taken before the violent conclusion, showing the veterans’ orderly demonstration. Their signs and unified presence highlight how the Depression transformed ordinary citizens into protesters. These men had fought for democracy abroad only to find themselves fighting for economic justice at home.

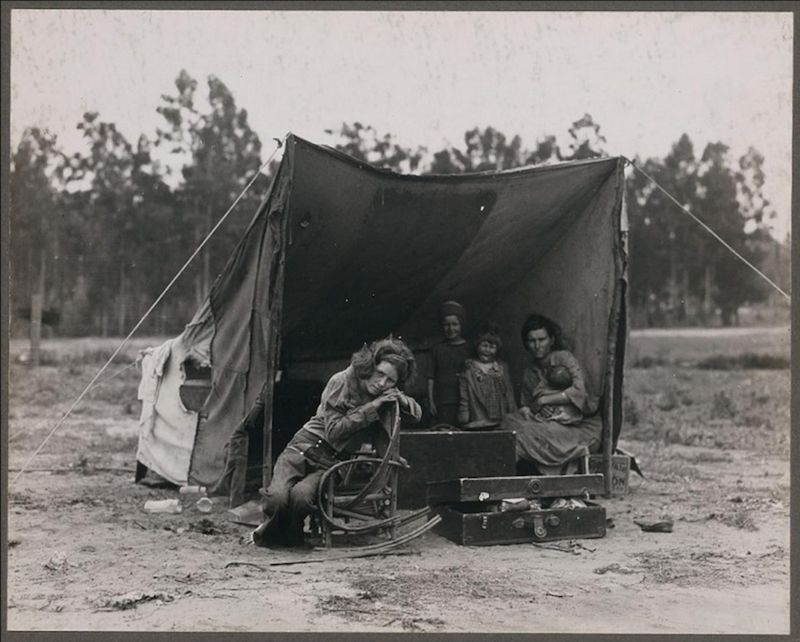

11. Tent Family

A young mother cradles her infant while two older children huddle close in the confined space of a ragged tent. Their temporary shelter, fashioned from canvas and branches, offers minimal protection from the elements. Families like this one represented America’s new nomads—agricultural workers who followed harvests up and down California, living in roadside camps with no running water or sanitation. After long days picking crops for meager wages, they returned to these makeshift homes to prepare meals over open fires. Lange’s intimate portrait shows how the Depression stripped away normal childhood experiences. The older children’s solemn faces reveal premature maturity born from witnessing their parents’ daily struggle. Yet the mother’s protective embrace also captures the fierce love that helped families endure these impossible conditions.

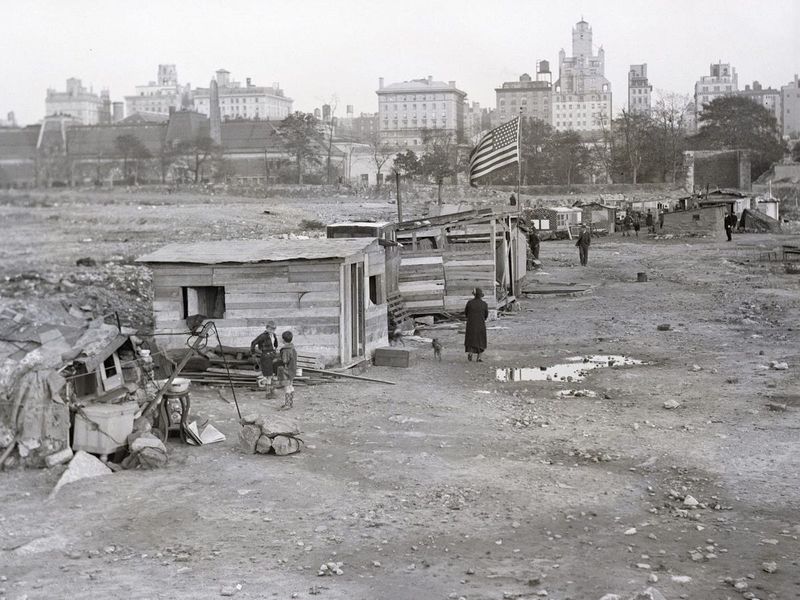

12. Hooverville

A sprawling village of makeshift shacks stretches across vacant land near an urban center. Constructed from scrap wood, cardboard, and discarded metal, these improvised homes housed thousands who had nowhere else to go. Named bitterly after President Herbert Hoover, whom many blamed for the Depression, these “Hoovervilles” appeared in cities nationwide. This particular settlement shows the ingenuity of desperate people—chimneys made from tin cans, walls from flattened food containers, and roofs from salvaged lumber. What makes this image particularly striking is the contrast between the shantytown and the city skyline visible in the background. The proximity of extreme poverty to urban wealth highlighted the economic inequality that the Depression had brutally exposed, with former working-class families literally living in the shadow of prosperity they could no longer access.

13. Flood Refugees

African American flood victims stand in line before a billboard ironically proclaiming “World’s Highest Standard of Living.” Their worn clothing and weary expressions contrast sharply with the smiling white family in the advertisement above them. When the Ohio River flooded in 1937, it compounded the suffering already inflicted by the Depression. Black Americans, facing both economic hardship and racial discrimination, were often last to receive relief and first to lose their homes in natural disasters. Margaret Bourke-White’s genius in this composition lies in capturing the stark divide between American mythology and reality. The billboard’s message of prosperity and the actual conditions of these displaced citizens creates one of the most powerful visual commentaries on race and class during the Depression era.

14. Coal Miner Family

A coal miner’s family gathers in their sparse cabin in West Virginia. Their gaunt faces and threadbare clothing tell of malnutrition and poverty that preceded the Depression but worsened dramatically during it. Mining families faced unique hardships during these years. When coal demand dropped, miners lost not just income but often their company-owned homes as well. This family’s living space reveals the bare minimum for survival—simple wooden furniture, a few cooking utensils, and walls papered with newspaper for insulation. Walker Evans captured both the material deprivation and the human connections that sustained these families. The physical closeness of family members in the frame suggests the emotional bonds that provided strength when material resources failed. Their direct gazes challenge viewers to see beyond statistics to the human cost of economic policies.

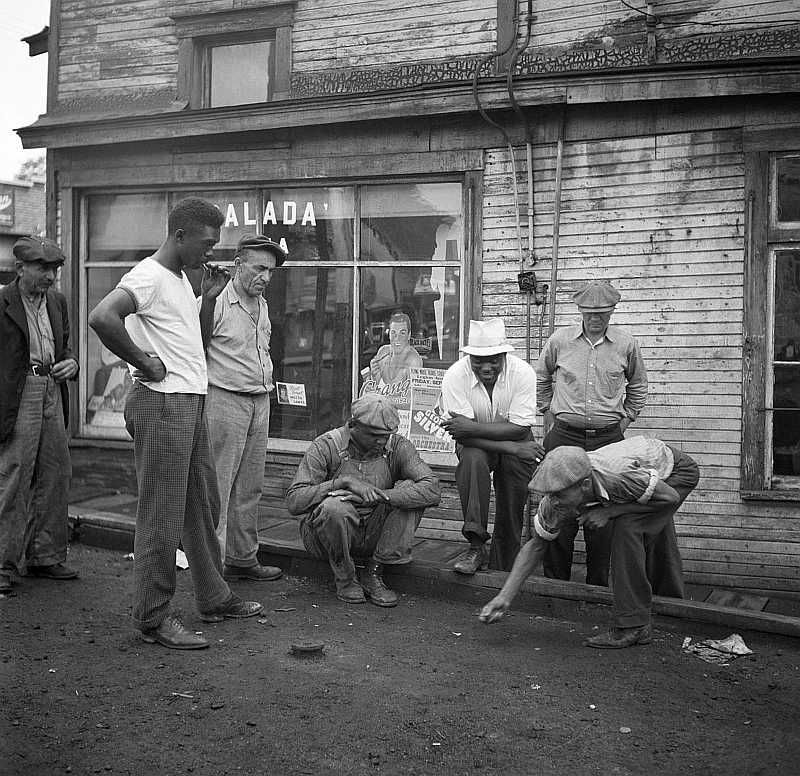

15. Day Laborers

A group of men huddle on a street corner at dawn, hoping to be chosen for a day’s labor. Some hold tools—shovels, hammers, paintbrushes—advertising their skills to potential employers who might drive by. The casual labor market became a last resort for millions during the Depression. Men would gather at known pickup spots before sunrise, competing for scarce jobs that might pay just enough for that day’s meals. The lucky ones would be selected; the rest would return home empty-handed. The anonymous photographer captured the quiet dignity of men who refused to give up. Despite repeated rejection, they continued to show up each morning, maintaining the routine of work even when work itself was scarce. Their weather-beaten faces reveal the toll of uncertainty and the determination to provide for their families however possible.

16. Black Blizzard

An apocalyptic wall of black dust towers over a small Texas town, dwarfing buildings and threatening to engulf everything in its path. Residents can only watch as the massive cloud approaches their community. These “black blizzards” could rise 10,000 feet high and travel at 60 miles per hour, turning day to night within minutes. Years of drought combined with poor farming practices had stripped the topsoil from millions of acres across the Great Plains, creating conditions for these devastating storms. George Marsh’s dramatic photograph captures the moment before impact, when the dust cloud appears almost supernatural in its menace. For residents of the Plains states, these storms meant not just property damage but respiratory illness, failed crops, and the slow death of communities that had flourished just years before.

17. Child Labor

Small hands move quickly over a cotton loom in a Southern textile mill. The child, no more than ten years old, stands on a box to reach the machinery, her thin face showing exhaustion beyond her years. Though child labor laws existed, economic desperation during the Depression forced many families to send children to work instead of school. Factory owners, facing their own financial pressures, often welcomed these young workers who could be paid less than adults. Lewis Hine, who had documented child labor since the early 1900s, found conditions worsening during the Depression. His photographs helped reveal how economic hardship had reversed decades of progress in protecting children’s rights. This image stands as a reminder that the youngest Americans often bore the heaviest burden of the crisis, sacrificing education and childhood for family survival.

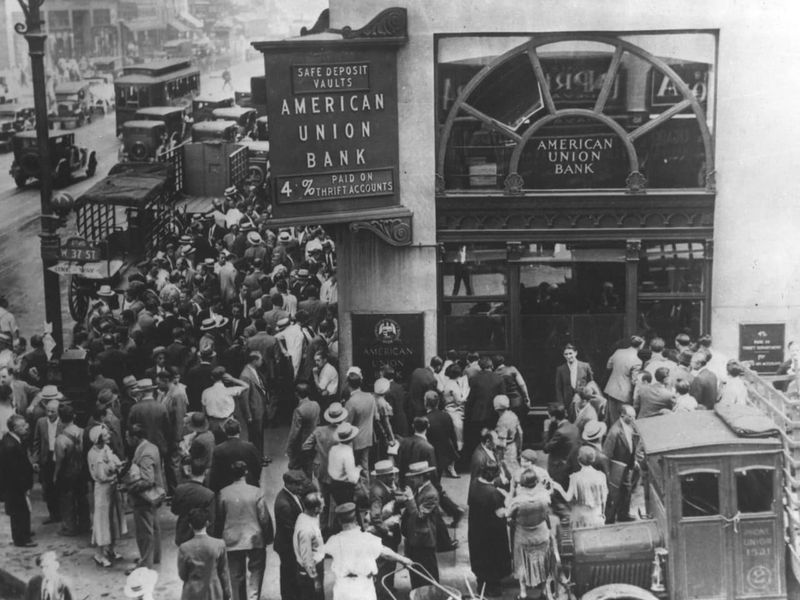

18. Bank Run

Panic etches itself across the faces of depositors crowded outside a closed bank, desperate to withdraw their life savings. The locked doors and “Closed” sign represent shattered trust in financial institutions that once seemed unshakable. Bank failures accelerated during the Depression’s early years, with over 9,000 banks collapsing between 1930 and 1933. Without deposit insurance, customers who couldn’t withdraw their money before a bank failed lost everything—savings, college funds, retirement accounts vanished overnight. This photograph captures the moment when abstract economic forces became painfully personal. Each face in the crowd represents a family facing potential ruin. The composition, showing the mass of humanity pressed against unyielding doors, powerfully symbolizes ordinary Americans’ helplessness against larger financial forces they neither controlled nor fully understood.

19. Migrant Car

An old sedan struggles down Route 66, loaded impossibly high with furniture, mattresses, and kitchen items. A family of six has somehow squeezed inside, leaving their Oklahoma farm behind for the promise of work in California. These “Okies”—though many came from other states too—formed one of America’s largest internal migrations. Fleeing both dust storms and bank foreclosures, approximately 400,000 people traveled west during the Depression years, often facing hostility when they arrived. Lange’s photograph captures both the desperate improvisation of these travelers and their determination to keep their family unit intact. The carefully tied household goods represent not just material possessions but connections to a former life and identity. Despite abandoning their homes, these migrants refused to abandon hope for a future where they might put down roots again.

20. New Deal Workers

Men in work clothes build a road through a rural landscape, their faces showing purpose rather than desperation for the first time in years. Their government-issued uniforms and organized activity mark a turning point in the Depression narrative. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration (WPA), put millions back to work on infrastructure projects across America. Unlike earlier relief efforts, these programs emphasized the dignity of work rather than charity. Russell Lee’s 1939 photograph captures the beginning of recovery, though full economic healing would require the wartime production of the 1940s. The straight road stretching toward the horizon serves as a powerful visual metaphor for a nation finally moving forward after a decade of hardship, with renewed confidence in both government institutions and their own capabilities.