When we talk about the fight for women’s voting rights, some names get left out of history books. Black women played a crucial role in the suffrage movement while facing both sexism and racism. They fought for the 19th Amendment knowing it wouldn’t fully protect their right to vote. Their work went beyond voting rights to include racial justice, education, and economic equality.

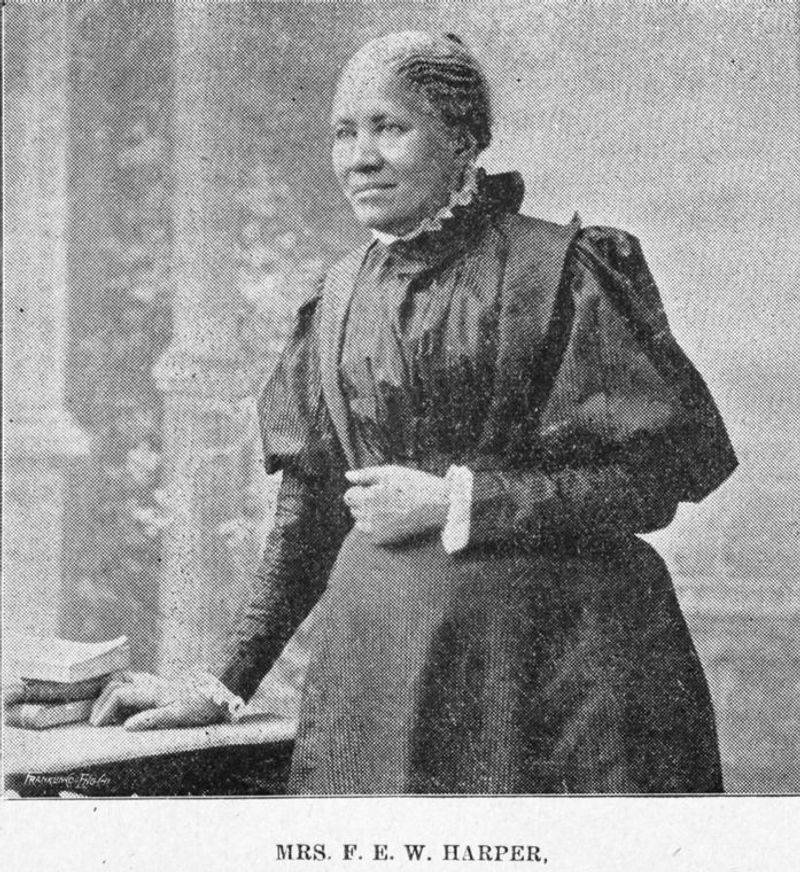

1. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper: The Poet of Protest

Born free in Baltimore in 1825, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper wielded her pen as a weapon against injustice. Her powerful novels and poetry addressed both racial and gender inequality at a time when Black women’s voices were routinely silenced. Harper’s 1866 speech at the Women’s Rights Convention revealed the divide in the suffrage movement when she boldly declared: “You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs.”

Harper stood her ground when white suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton opposed the 15th Amendment giving Black men the right to vote. She understood that for Black women, voting rights couldn’t be separated from racial justice. Her novel “Iola Leroy” (1892) became one of the first published by a Black woman in America.

Throughout her long career, Harper lectured across the country, helped enslaved people escape through the Underground Railroad, and advocated for temperance. Her legacy reminds us that the fight for equality requires addressing multiple forms of oppression simultaneously. Harper’s work connected voting rights to economic justice and protection from violence, creating a blueprint for modern intersectional activism.

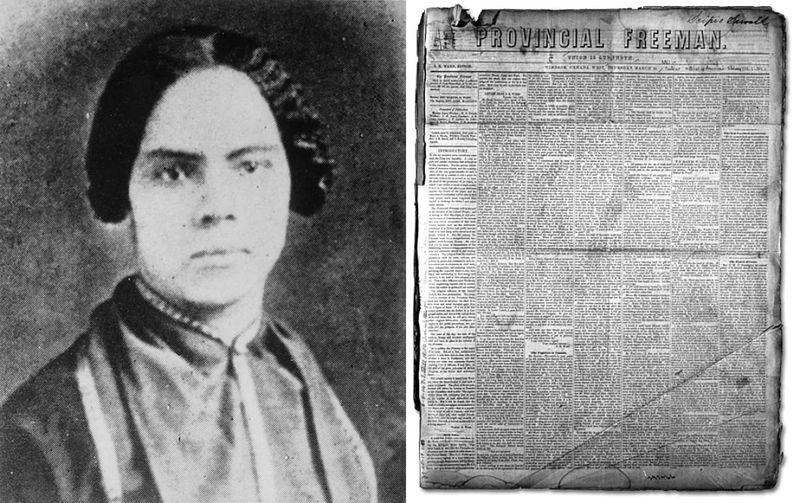

2. Mary Ann Shadd Cary: Breaking Barriers with Ink and Law

“The crowning glory of American citizenship is that it may be shared equally by people of every nationality, complexion, and sex.” These powerful words came from Mary Ann Shadd Cary, a woman of many firsts. When the Fugitive Slave Act threatened free Black Americans in 1850, Shadd Cary didn’t just flee to Canada – she established herself as North America’s first Black woman newspaper editor.

Her paper, The Provincial Freeman, boldly advocated for abolition and women’s rights when most publications wouldn’t touch these topics. Not content with journalism alone, Shadd Cary later became one of America’s first Black female lawyers after graduating from Howard University in 1883 at age 60. Her legal training strengthened her suffrage arguments.

In 1874, she testified before Congress, applying the American principle against taxation without representation to women’s situation. While fighting for women’s rights, she never abandoned her commitment to racial justice. Shadd Cary embodied the determination of Black suffragists who refused to choose between their identities as women and as Black Americans, insisting both deserved equal citizenship.

3. Mary Church Terrell: Education as Liberation

The daughter of formerly enslaved people who became wealthy business owners, Mary Church Terrell transformed her privileged education into a lifetime of activism. After becoming one of the first Black women to earn a college degree from Oberlin in 1884, Terrell dedicated herself to proving Black women’s intellectual capabilities through action rather than words.

When a close friend was lynched in Memphis, Terrell channeled her grief into founding the National Association of Colored Women in 1896. The organization’s motto, “Lifting as we climb,” reflected her belief that educated Black women had a responsibility to help others. Her suffrage work emphasized how the ballot could dismantle Jim Crow laws that kept Black Americans as second-class citizens.

Remarkably, Terrell’s activism spanned nearly a century. At age 90, she led successful protests to desegregate Washington D.C. restaurants in the 1950s, living to see the early civil rights movement. Throughout her life, she maintained that voting rights were meaningless without economic opportunity and social equality. Her bilingual education allowed her to represent Black women internationally, bringing their concerns to a global audience.

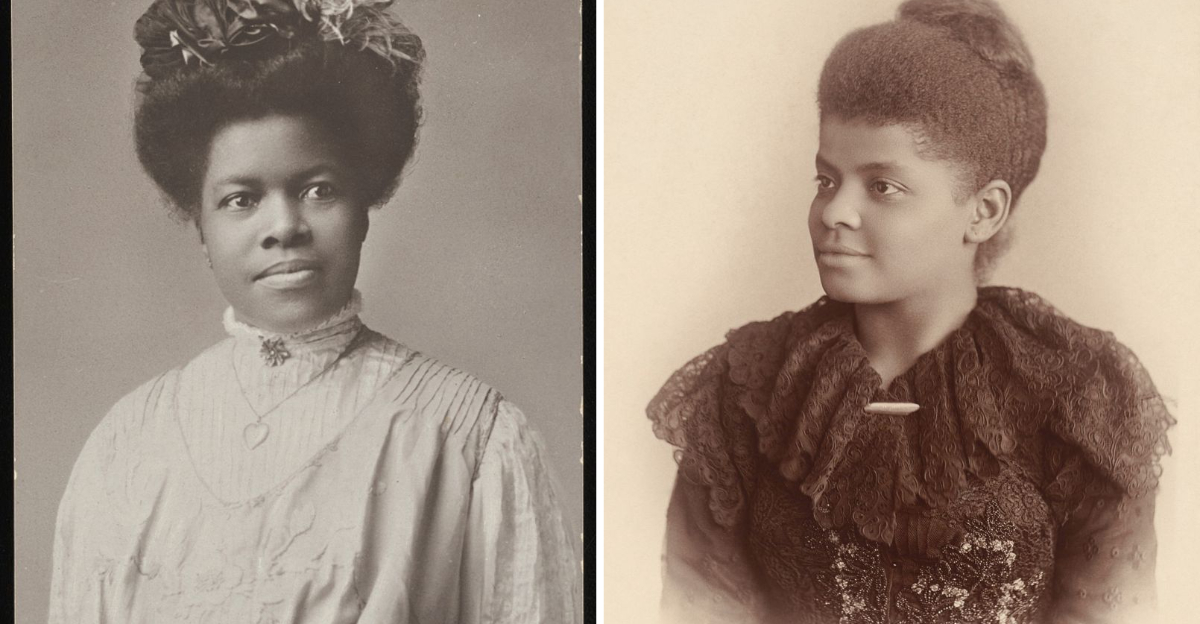

4. Ida B. Wells: Fearless Journalist Against Lynching

After losing her parents to yellow fever at age 16, Ida B. Wells refused to let her younger siblings be separated. This early stand against injustice foreshadowed her lifelong courage. When forcibly removed from a whites-only train car in 1884 despite having a first-class ticket, Wells sued the railroad—and initially won before the verdict was overturned.

Wells’ investigative journalism exposed the truth about lynching: most victims weren’t accused of crimes against women as claimed, but were successful Black businessmen targeted out of economic jealousy. Her findings published in “Southern Horrors” forced her to flee Memphis when her newspaper office was destroyed by a white mob. Undeterred, she continued her anti-lynching campaign from Chicago.

During the 1913 Washington suffrage parade, Wells refused orders to march in the segregated section, boldly joining the Illinois delegation instead. She founded the Alpha Suffrage Club to mobilize Black women voters in Chicago, understanding that political power could help fight racial violence. Wells co-founded the NAACP but later criticized the organization when she felt it wasn’t aggressive enough in fighting lynching.

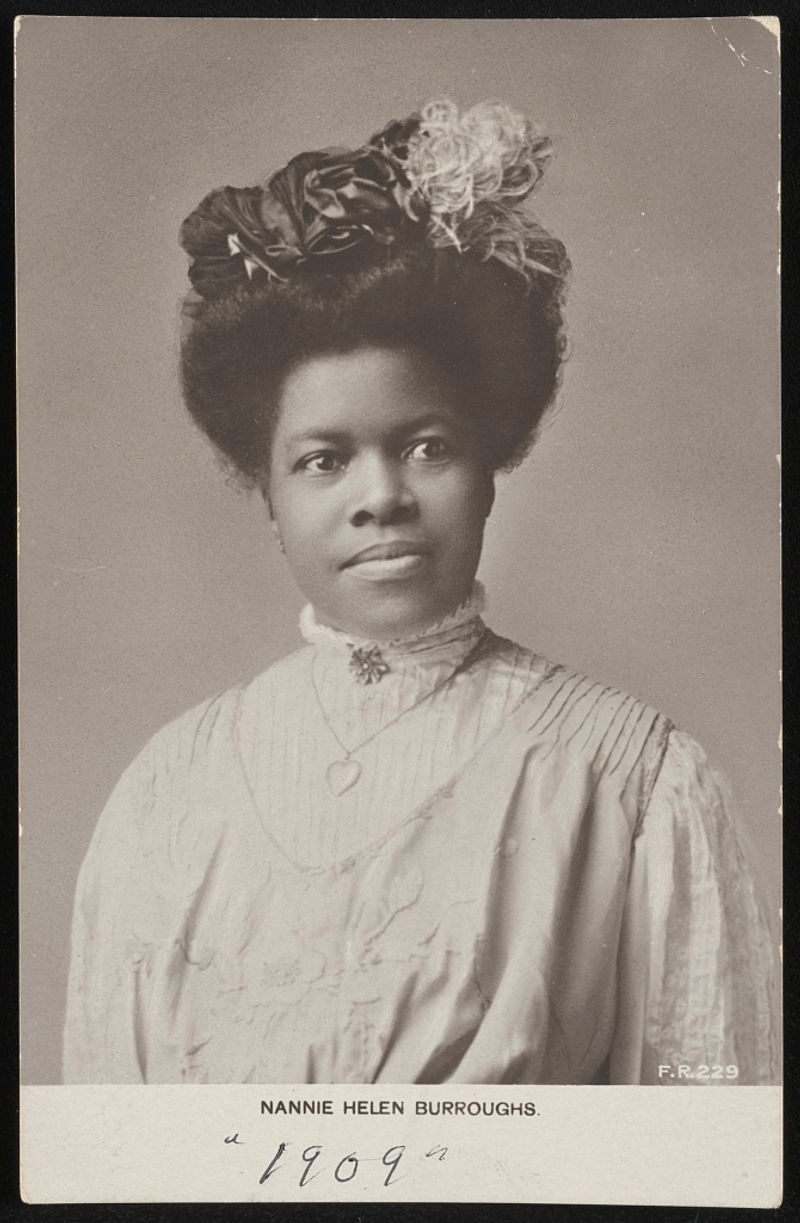

5. Nannie Helen Burroughs: Champion of Working Women

“We specialize in the wholly impossible” was the motto Nannie Helen Burroughs chose for her National Training School for Women and Girls. Established in 1909 in Washington D.C., the school embodied Burroughs’ belief that economic independence was essential for true freedom. When denied teaching positions because her skin was considered too dark, Burroughs created her own opportunity and then extended it to thousands of others.

Her school’s curriculum balanced academic subjects with vocational training and political education. Students learned trades alongside Black history and civic engagement at a time when most educational institutions for Black women focused solely on domestic service. Burroughs saw the vote as a tool for correcting harmful stereotypes, declaring: “When the ballot is put into the hands of the American woman, the world is going to get a correct estimate of the Negro woman.”

A devout Baptist, Burroughs also organized women within the church, founding the Women’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention. Her religious faith fueled rather than hindered her political activism. Throughout her 82 years, Burroughs remained committed to the idea that economic justice, religious faith, and political rights formed an inseparable foundation for Black women’s advancement.