Books have an incredible power to change how we see the world around us. Some stories entertain us for a while, but others stay with us forever, challenging our beliefs and opening our minds to new ideas. Over the past century, certain books have sparked conversations, launched movements, and even changed the course of history.

1. 1984 by George Orwell (1949)

Published shortly after World War II, this nightmarish vision of a surveillance state continues to send shivers down readers’ spines. Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece introduced terms like “Big Brother,” “doublethink,” and “thoughtcrime” that have become part of our everyday language.

The book follows Winston Smith’s dangerous rebellion against a government that controls not just actions, but thoughts themselves. Its warnings about propaganda, technology, and government overreach feel startlingly relevant in our digital age of data collection and privacy concerns.

2. A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking (1988)

Stephen Hawking accomplished something extraordinary with this bestseller – he made the cosmos accessible to everyday readers. Despite covering mind-bending concepts like black holes, the big bang, and the nature of time itself, Hawking’s clear explanations invite non-scientists into conversations previously reserved for physics professors.

What makes this achievement even more remarkable is that Hawking wrote it while battling ALS, using specialized computer equipment to communicate. The book’s enduring popularity proves that deep human curiosity about our universe transcends academic boundaries.

3. The Second S*x by Simone de Beauvoir (1949)

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” With this revolutionary statement, philosopher Simone de Beauvoir launched modern feminist thought. Her groundbreaking analysis examined how society, not biology, shapes female experience throughout history.

The book meticulously documents how literature, myths, and social structures have defined women as “other” – secondary to men. De Beauvoir’s work remains startlingly relevant today, offering insights on everything from childhood socialization to marriage dynamics.

Many readers discover that feelings they thought were personal shortcomings are actually shared experiences shaped by cultural forces.

4. Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter (1979)

Reading this Pulitzer Prize-winner feels like taking your brain to an intellectual playground. Hofstadter weaves together seemingly unrelated subjects – a mathematician’s logic theorems, an artist’s impossible drawings, and a composer’s intricate fugues – to explore the nature of consciousness itself.

The book playfully uses dialogues between fictional characters to demonstrate self-reference and recursive patterns. These same patterns appear across mathematics, art, music, and potentially, the human mind.

Readers willing to tackle this challenging journey are rewarded with a completely new way of thinking about thinking – and possibly, what makes us human.

5. The Road to Serfdom by Friedrich Hayek (1944)

Written during World War II by Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, this passionate defense of individual liberty warned that even well-intentioned government planning could lead to tyranny. The book challenged the growing post-war consensus that centralized economic control was the path to prosperity and equality.

Hayek’s arguments sparked fierce debates that continue today about the proper role of government in society. His central insight – that dispersed knowledge among millions of individuals cannot be effectively centralized – remains a cornerstone of free-market thinking.

The book’s influence extends far beyond economics, shaping political movements across decades.

6. Orientalism by Edward Said (1978)

Edward Said’s revolutionary work forever changed how we think about cultural representation. The Palestinian-American scholar meticulously documented how Western literature, art, and scholarship had created a distorted, exotic image of “the East” that served colonial interests.

Through careful analysis of everything from academic texts to popular novels, Said revealed how these representations weren’t innocent mistakes but systems of power. His work helped launch the field of postcolonial studies, giving voice to perspectives previously marginalized.

The book’s impact extends far beyond academia – its insights help us recognize how media representations of different cultures shape our worldviews today.

7. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S. Kuhn (1962)

Before Kuhn, most people imagined science as a steady march toward truth. This groundbreaking book completely reimagined how scientific progress actually happens. Kuhn introduced the concept of “paradigm shifts” – revolutionary changes in scientific thinking that completely transform a field.

Using historical examples like the Copernican revolution, Kuhn showed that science doesn’t simply accumulate facts. Instead, scientists work within shared frameworks that occasionally undergo dramatic upheavals.

The term “paradigm shift” has since escaped the boundaries of science, becoming cultural shorthand for any fundamental change in thinking – a testament to the book’s profound influence.

8. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932)

While Orwell feared those who would ban books, Huxley feared no one would want to read them at all. His chilling vision shows a society controlled not through fear, but through pleasure and distraction. Citizens are genetically engineered, conditioned from birth, and kept docile with recreational sex and “soma” – a perfect happiness drug.

The novel’s genius lies in making this dystopia seductive. Many characters seem content in their carefully controlled lives.

Modern readers often find Huxley’s predictions unnervingly accurate – from our entertainment obsessions to pharmaceutical solutions for unhappiness to the growing power of technology to shape human experience.

9. The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker (1973)

Why do humans build monuments, seek fame, create art, or wage war? According to Becker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning work, these diverse activities share a common source: our desperate attempts to deny our mortality.

The book draws on psychology, anthropology, and philosophy to argue that human civilization itself is an elaborate defense mechanism. Our awareness of death creates unbearable anxiety that we manage through “immortality projects” – efforts to create lasting meaning.

Becker’s insights help explain everything from religious fundamentalism to celebrity worship. The book offers no easy solutions but invites readers to live more authentically by confronting our deepest fears.

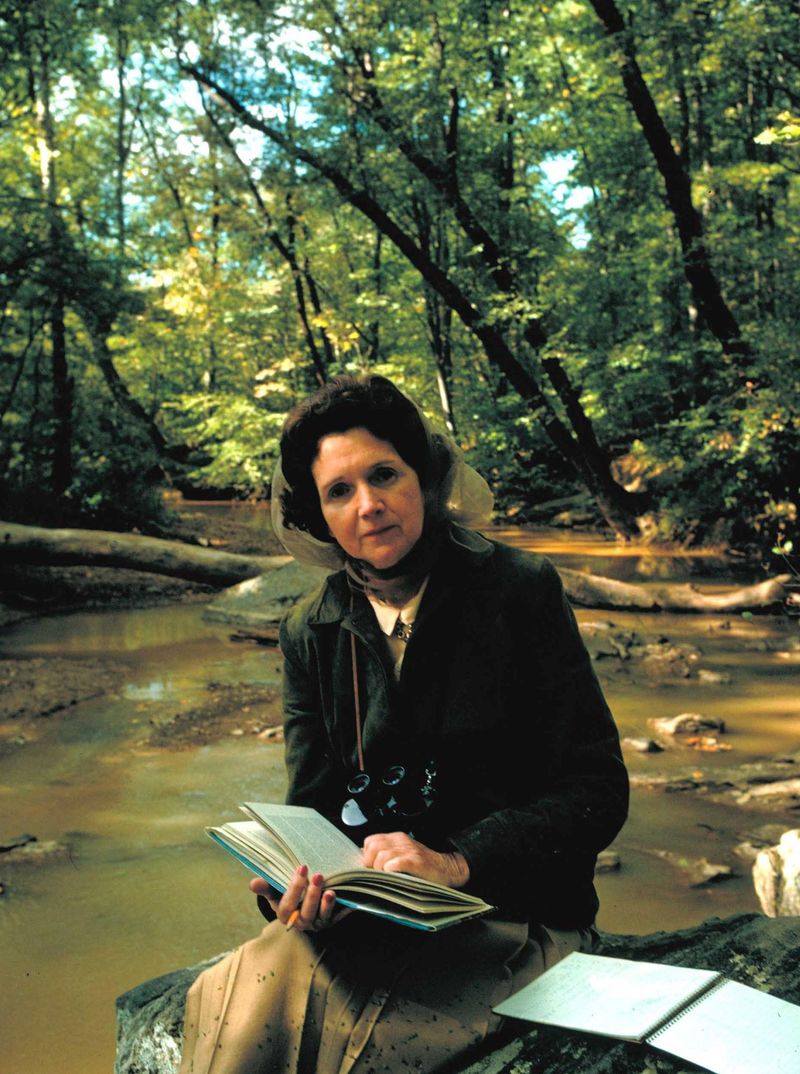

10. Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (1962)

“Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent.” With these haunting words, marine biologist Rachel Carson launched the modern environmental movement.

Carson’s meticulous research documented how pesticides like DDT were poisoning entire ecosystems, from insects to birds to humans. The chemical industry attacked her personally, but her scientific evidence proved irrefutable.

Within a decade, DDT was banned, the Environmental Protection Agency was created, and millions of ordinary citizens began thinking differently about humanity’s relationship with nature – all because one scientist dared to speak out.

11. Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault (1975)

Foucault’s fascinating history of prisons begins with a gruesome 18th-century public execution and ends with the seemingly more humane modern prison system. But his shocking conclusion? Modern punishment might actually represent more control, not less.

The book explores how power operates through surveillance, classification, and the creation of “docile bodies.” Foucault’s insights extend far beyond prison walls to schools, hospitals, factories – anywhere people are organized and observed.

His famous analysis of the “panopticon” – a prison design where inmates never know when they’re being watched – offers a powerful metaphor for understanding how modern society functions through internalized self-discipline.

12. The Master and His Emissary by Iain McGilchrist (2009)

Could the physical structure of our brains explain the course of Western civilization? Psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist makes this audacious claim by exploring the divided nature of the human brain.

The left hemisphere excels at narrow focus, analysis, and manipulation – while the right handles broader awareness, context, and meaning. McGilchrist argues that Western culture has increasingly favored left-brain approaches, creating a dangerously imbalanced worldview.

The book weaves together neuroscience, philosophy, art history, and literature to make its case. Readers may never see themselves – or society – the same way again after considering how their divided brains shape perception.

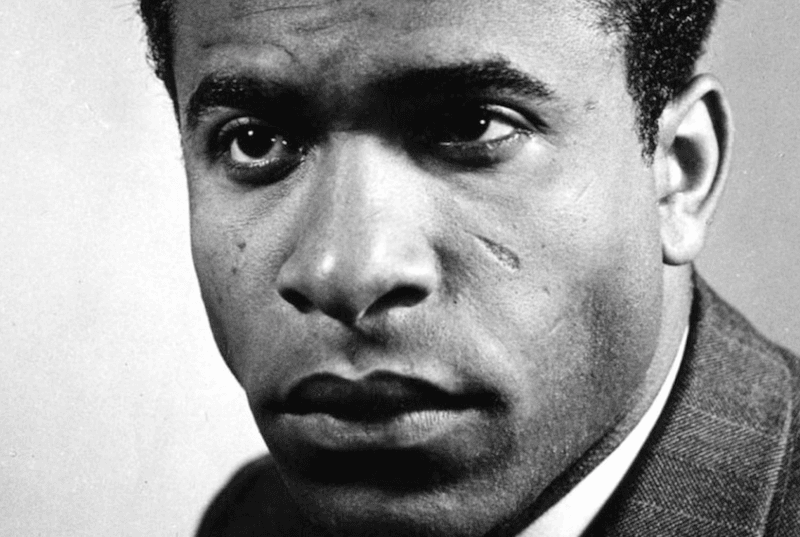

13. Black Skin, White Masks by Frantz Fanon (1952)

Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist from Martinique, wrote this revolutionary text examining the psychological damage inflicted by colonialism on both the colonized and colonizers. Drawing from his own experiences, Fanon explores how racism becomes internalized, creating profound identity conflicts.

The book combines personal narrative, psychiatric case studies, literary analysis, and philosophical reflection. Fanon’s unflinching examination of how language, relationships, and cultural representations maintain racial hierarchies remains painfully relevant.

His work influenced anti-colonial movements worldwide and continues to provide essential insights into race, identity, and power dynamics in contemporary society.

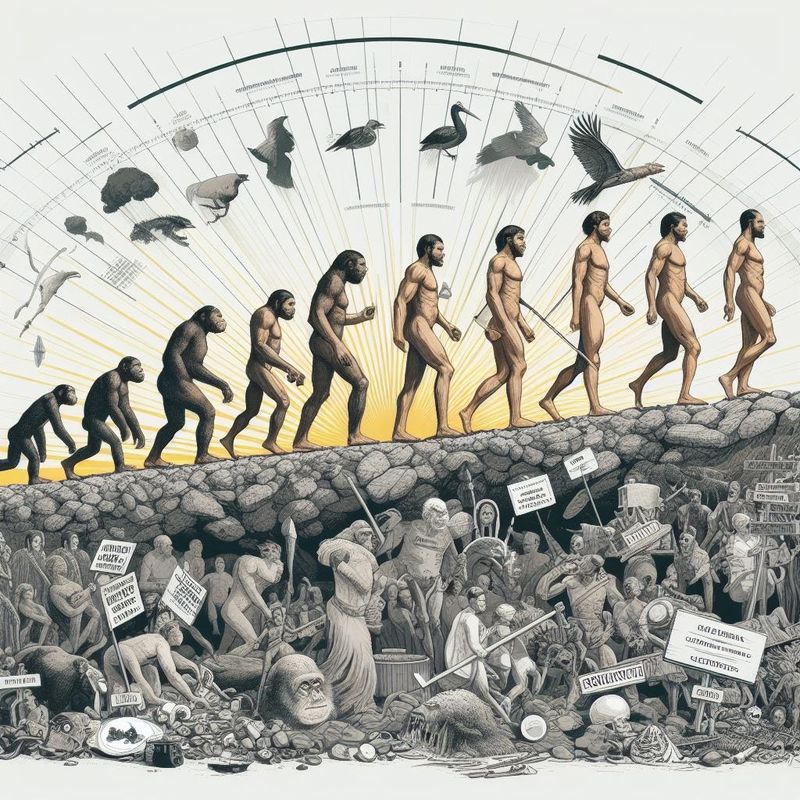

14. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins (1976)

Dawkins’ revolutionary book flipped our understanding of evolution upside down. Rather than seeing organisms as the central players, he proposed viewing genes themselves as the fundamental units of selection – using bodies merely as survival machines.

This perspective elegantly explains puzzling behaviors like altruism between relatives (they share genes) and parent-offspring conflicts. Dawkins introduced the concept of “memes” – ideas that replicate and evolve like genes – creating an entirely new field of study.

Despite controversies surrounding Dawkins himself, the book’s core insights have transformed biology. Its accessible writing brings complex evolutionary concepts to life through memorable examples and clear explanations.

15. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari (2011)

How did a seemingly unremarkable ape become Earth’s dominant species? Harari’s global phenomenon offers a sweeping yet accessible tour through human history, challenging readers to reconsider everything they thought they knew about our species.

The book’s most provocative claim? Much of human success relies on our unique ability to believe in shared fictions – from religions and nations to money and corporations. These collective myths enable large-scale cooperation unlike anything in the animal kingdom.

Harari combines insights from biology, anthropology, economics and more into a compelling narrative. His fresh perspective helps readers see familiar human institutions as the strange, remarkable constructions they truly are.

16. To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927)

Virginia Woolf’s modernist masterpiece doesn’t rely on dramatic plot twists or action sequences. Instead, it takes readers directly into the minds of its characters during an ordinary family vacation, revealing how rich and complex our inner lives truly are.

Through her revolutionary “stream of consciousness” technique, Woolf captures the fluid, fragmentary nature of human thought. Seemingly trivial moments – a dinner party, a painting session, a postponed trip – become profound explorations of art, relationships, and the passage of time.

The novel’s middle section, where time accelerates and an empty house decays, creates one of literature’s most powerful meditations on mortality and impermanence.

17. The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon (1961)

Written during Algeria’s bloody war for independence, this explosive manifesto became a handbook for anti-colonial movements worldwide. Fanon, a psychiatrist who joined Algeria’s liberation struggle, unflinchingly examines the psychological and physical violence of colonialism.

His most controversial argument? That oppressed peoples might need revolutionary violence to overcome centuries of dehumanization and reclaim their dignity and cultural identity.

Beyond its historical significance in liberation struggles across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the book continues to influence discussions about structural violence, cultural recovery, and the lingering psychological effects of historical trauma in post-colonial societies.