Long before Hollywood embraced diversity, a group of talented Black filmmakers carved their own path in the silent film era.

These visionaries created powerful stories that showcased authentic Black experiences when mainstream cinema ignored or stereotyped them.

Their groundbreaking work established independent Black cinema against overwhelming odds, yet their contributions remain largely uncelebrated in film history.

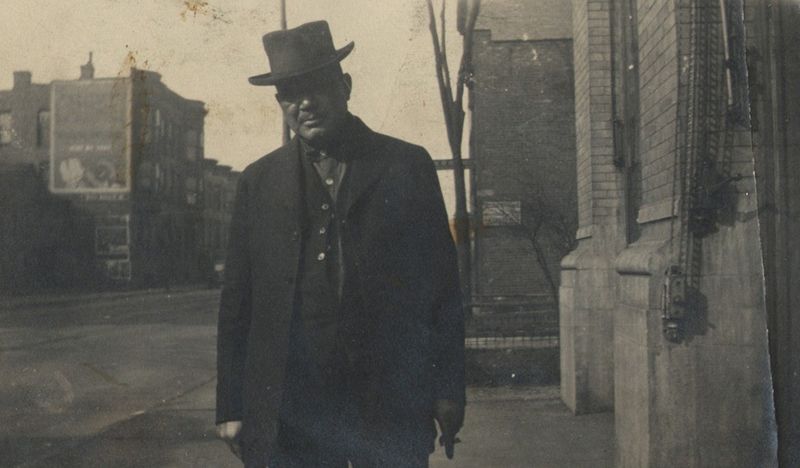

1. Oscar Micheaux: The Trailblazing Filmmaker

Born to former slaves in 1884, Oscar Micheaux transformed from novelist to filmmaker when Hollywood refused to adapt his book The Homesteader. Undeterred, he produced it himself in 1919, creating history as the first feature-length film by a Black director. Over three decades, Micheaux directed more than 40 films that boldly challenged racial stereotypes and addressed controversial issues like lynching and interracial relationships. His company distributed films directly to Black theaters nationwide. Remarkably, Micheaux accomplished all this with minimal resources, often shooting scenes in a single take and funding projects by selling stock in his production company to Black investors.

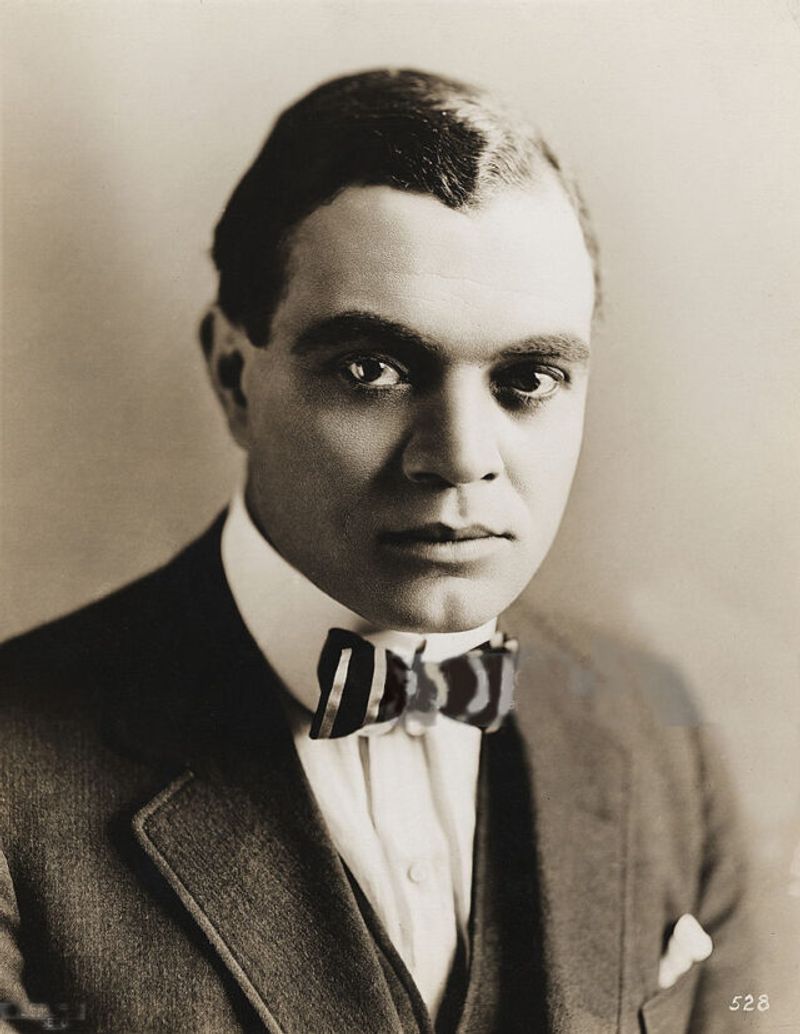

2. Noble Johnson: Hollywood Actor Turned Independent Producer

Standing six feet tall with striking features, Noble Johnson achieved the rare feat of crossing over into mainstream Hollywood roles during the silent era. His acting career included appearances in films like The Mummy (1932) and King Kong (1933). Frustrated by limited opportunities for Black performers, Johnson co-founded Lincoln Motion Picture Company in 1916 – the first Black-owned film production company in America. The company produced race films that portrayed African Americans with dignity and complexity. Johnson’s dual career required secrecy; many white Hollywood producers never knew about his pioneering work creating films for Black audiences, which might have cost him mainstream roles.

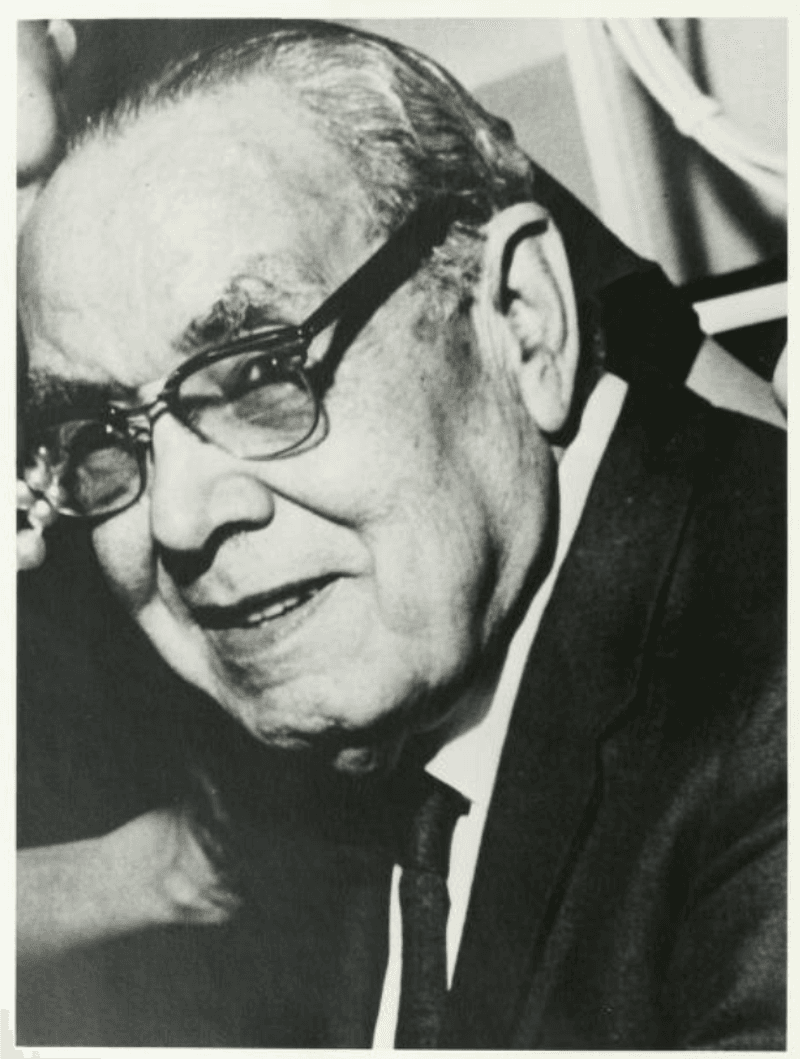

3. George P. Johnson: The Business Mind Behind Lincoln Films

While his brother Noble appeared on screen, George P. Johnson worked tirelessly behind the scenes as Lincoln Motion Picture Company’s business manager and marketing genius. His innovative distribution methods included traveling throughout the South with film reels, arranging screenings in Black churches and community centers. Johnson maintained meticulous records of early Black cinema, preserving letters, photographs, and business documents that might otherwise have been lost to history. His collection eventually became a priceless archive for film historians. After Lincoln Pictures closed in 1921, Johnson continued promoting Black cinema as a booking agent, connecting Black-owned theaters with race films from various producers.

4. Tressie Souders: Breaking the Gender Barrier

In 1922, when both the film industry and society restricted women’s opportunities, Tressie Souders shattered multiple barriers with her film A Woman’s Error. The Black press celebrated her as the first African American woman director, with headlines announcing her achievement in The Chicago Defender. Little biographical information about Souders survives, making her perhaps the most mysterious figure on this list. Her film explored complex themes of racial passing and identity – topics rarely addressed in mainstream cinema of the era. Sadly, no copies of A Woman’s Error are known to exist today, making it one of many lost treasures from early Black cinema history.

5. Maria P. Williams: Pioneer Producer and Businesswoman

Maria P. Williams wore many hats – newspaper publisher, community activist, and groundbreaking filmmaker. With her husband Jesse, she established Western Film Producing Company in Kansas City, creating opportunities for Black artists excluded from mainstream studios. Her 1923 thriller The Flames of Wrath showcased her multiple talents as producer, writer, and distributor. Williams personally handled the business negotiations, promotion, and distribution – extraordinary responsibilities for any woman of that era, let alone a Black woman. Beyond filmmaking, Williams organized community events and published articles advocating for greater Black representation in cinema, understanding film’s power to shape public perception.

6. Clarence Brooks: From Broadway to Pioneering Actor

With classical training and Broadway experience, Clarence Brooks brought refined acting techniques to early Black cinema. His performances in Lincoln Motion Picture Company films like The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition (1916) showcased dignified Black characters with professional careers – revolutionary portrayals for the time. Brooks eventually crossed over to mainstream Hollywood, appearing in the 1929 film Hearts in Dixie. However, he refused stereotypical roles that demeaned African Americans, often turning down more lucrative opportunities that contradicted his principles. Beyond acting, Brooks served as a casting director, using his position to create opportunities for other Black performers struggling to find meaningful work in a segregated industry.

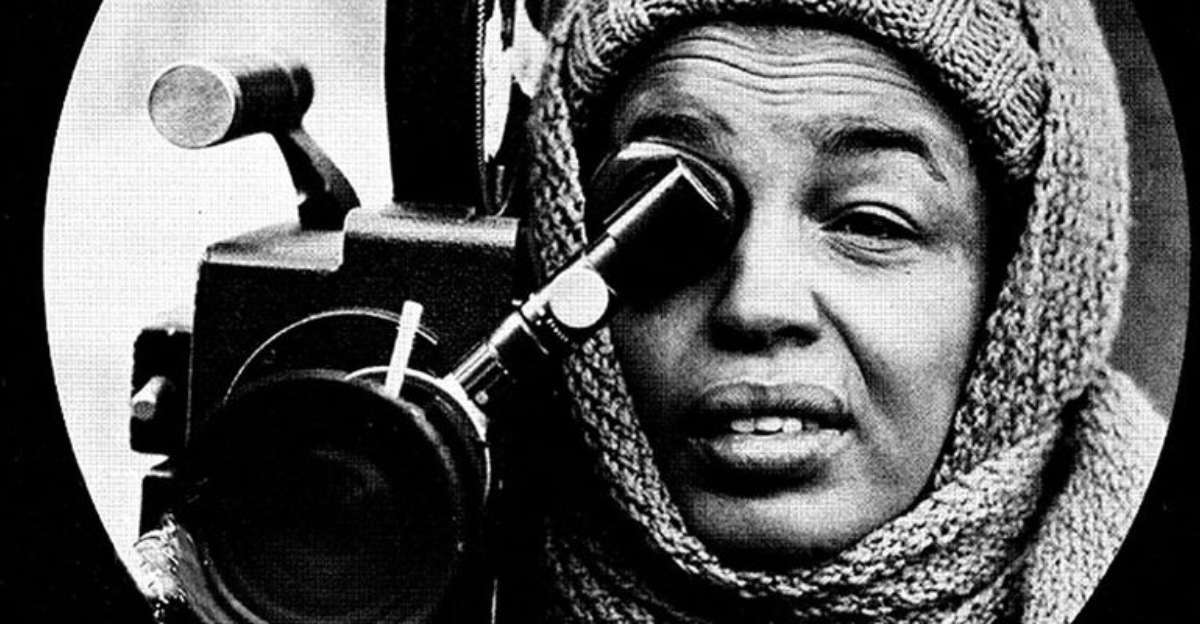

7. William Foster: America’s First Black Filmmaker

Before anyone on this list made their first film, William Foster was already blazing trails. His Foster Photoplay Company, established in 1910, predated Oscar Micheaux’s work by nearly a decade. As a former sports writer, Foster understood the power of media to shape public perception. Foster wore multiple hats – writer, director, producer, and distributor – often working with amateur actors recruited from Chicago’s vibrant Black community. His first film, The Railroad Porter (1912), deliberately countered the negative stereotypes found in white-produced films. Foster also created the first Black film advertising agency, promoting his work through clever marketing campaigns in Black newspapers across America.

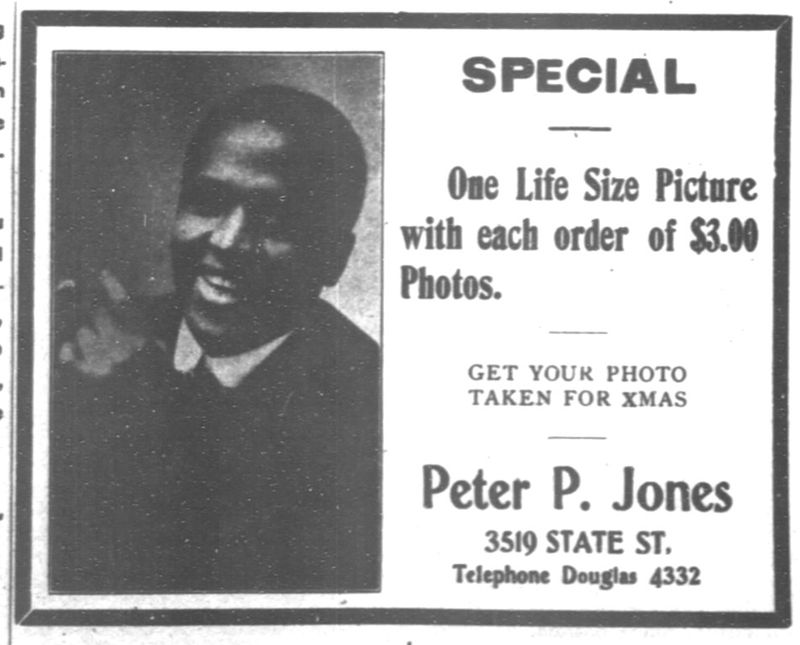

8. Peter P. Jones: The Educational Filmmaker

While many early Black filmmakers focused on entertainment, Peter P. Jones recognized cinema’s educational potential. His 1909 documentary A Trip to Tuskegee showcased Booker T. Washington’s famous institute, creating a visual record of Black educational achievement rarely seen in mainstream media. Jones began his career as a photographer before transitioning to motion pictures, bringing a distinctive visual style to his documentary work. His films often highlighted Black professionals, entrepreneurs, and educators – positive images that contradicted prevalent stereotypes. As an independent producer in Los Angeles, Jones maintained a photography studio that doubled as a gathering place for early Black Hollywood talents to network and share resources.

9. James and Eloyce Gist: Cinema as Spiritual Mission

Husband-and-wife team James and Eloyce Gist created films with a divine purpose. As traveling evangelists in the 1920s, they produced religious-themed movies shown in churches and community halls across America, reaching audiences overlooked by commercial theaters. Their most famous work, Hell-Bound Train (circa 1930), used powerful visual metaphors to illustrate the consequences of sin. Each railcar depicted a different moral failing – drinking, gambling, dancing – with Satan himself as the conductor. The Gists’ films blended silent film aesthetics with religious revival traditions, creating a unique cinematic experience. Their work represents an important intersection of Black spiritual practice and early independent filmmaking.