Long before the celebrated Tuskegee Airmen made history during World War II, a brave group of Black men and women challenged racial barriers in aviation. They pursued their dreams of flight despite facing discrimination at every turn. These extraordinary individuals opened doors for future generations by becoming the first to earn pilot licenses, establish flight schools, and demonstrate that the sky truly was for everyone.

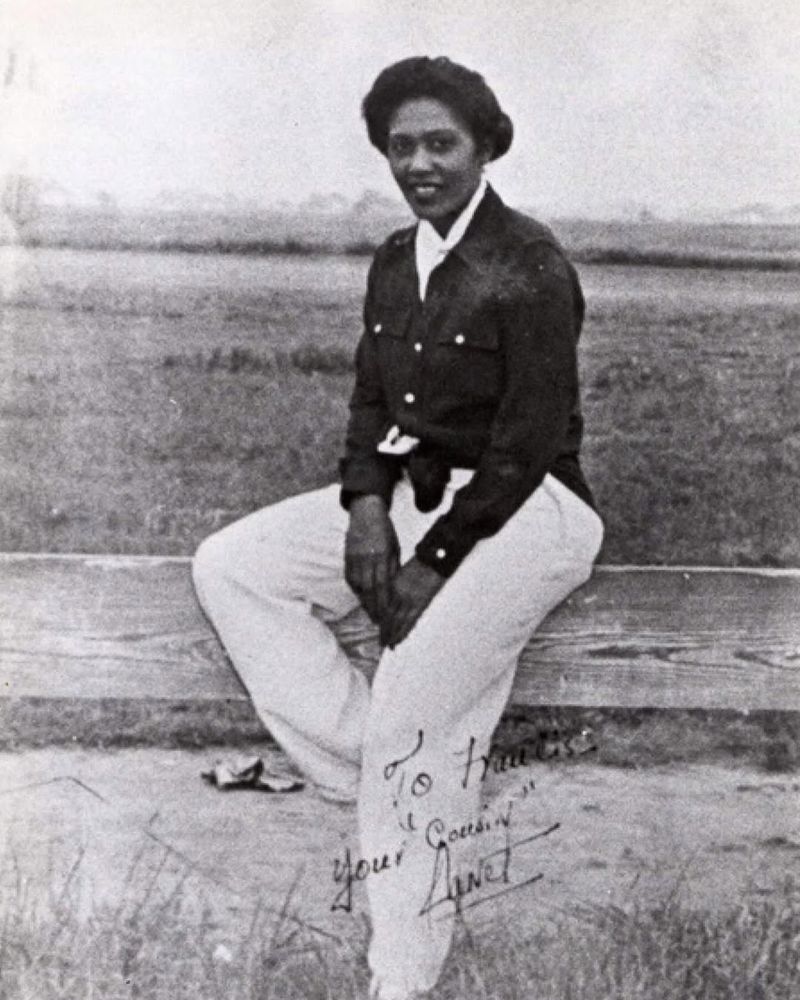

1. Bessie Coleman: Breaking Barriers in the Sky

When American flight schools slammed their doors in her face, Bessie Coleman simply looked across the Atlantic. In 1921, she journeyed to France and became the first African American woman to earn a pilot’s license.

Known as “Queen Bess,” Coleman thrilled crowds with death-defying aerial stunts at airshows across America. She refused to perform anywhere that discriminated against Black attendees.

Her dream of opening a flight school for African Americans was cut short by her tragic death in 1926, but her legacy of determination inspired countless others to pursue aviation despite seemingly insurmountable odds.

2. Eugene Bullard: The Black Swallow of Death

Escaping racial violence in Georgia at just 11 years old, Eugene Bullard stowed away on a ship to Europe. His extraordinary journey led him to become the world’s first Black combat pilot, flying for France during World War I.

The French embraced his talents while America remained segregated. His plane bore a personal insignia: a heart with a knife through it and the words “All Blood Runs Red.”

Despite his heroic service and 20 aerial victories, when Bullard later applied to join the U.S. Army Air Corps, he was rejected solely because of his race. France, however, awarded him their highest military honors.

3. Emory Malick: America’s Hidden Aviation Pioneer

In an era when aviation history focused almost exclusively on white pioneers, Emory Malick quietly made history. His groundbreaking achievement in 1912 – earning his pilot’s license – remained largely unknown for decades due to historical erasure.

Flying a fragile wooden and fabric Curtiss pusher biplane, Malick took to Pennsylvania skies when powered flight itself was still considered dangerous and experimental. His courage was extraordinary considering the additional risks he faced as a Black man in Jim Crow America.

Recent historical research has finally brought his remarkable story to light, revealing him as one of America’s earliest licensed pilots regardless of race.

4. William Powell: Creating Pathways for Black Pilots

After being denied entry to American aviation schools, World War I veteran William Powell refused to accept defeat. His response? Found the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in 1929, creating opportunities for Black pilots when none existed elsewhere.

Powell believed aviation represented more than transportation—it symbolized freedom and progress. “Black Wings,” his influential 1934 book, urged African Americans to claim their place in the skies and the aviation industry.

Under his leadership, the club organized the first all-Black air show in America, demonstrating to thousands of spectators that African Americans belonged in aviation. His motto: “Aviation is the doorway to opportunity.”

5. Hubert Julian: The Daredevil Black Eagle of Harlem

Trinidad-born Hubert Julian brought flair and spectacle to aviation that captured public imagination. Nicknamed “The Black Eagle of Harlem,” his dramatic parachute jumps over New York City drew massive crowds in the 1920s.

Julian’s larger-than-life personality matched his ambitious stunts. When he announced plans to fly across the Atlantic in 1924, Harlem residents raised funds to support this audacious goal—though his first attempt ended with his plane crashing into Flushing Bay.

He later served as a pilot for Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, connecting African American aviation to the Pan-African movement. His colorful aviation career spanned decades despite constant racial barriers.

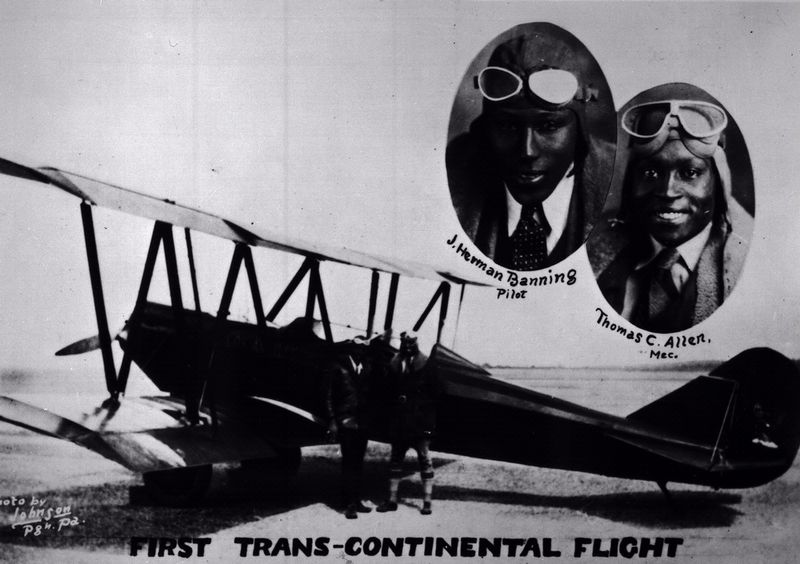

6. James Herman Banning: Coast-to-Coast Against All Odds

In 1932, when James Herman Banning and Thomas Allen completed the first transcontinental flight by Black pilots, they called it the “Flying Hoboes” journey. This wasn’t just a nickname—it reflected the harsh reality of having to beg for fuel, food, and lodging across America.

Their aging aircraft, purchased for just $600, constantly threatened to fail them. At each landing, they faced rejection from white-owned businesses and relied on Black communities for essential support.

The 21-city, 3,300-mile journey from Los Angeles to New York took 21 days. Each mile represented not just distance covered, but barriers broken in an America that refused to believe Black pilots could achieve such a feat.

7. Thomas C. Allen: The Mechanic Who Made History Possible

Without Thomas Allen’s mechanical genius, the first transcontinental flight by Black aviators would never have succeeded. His skillful hands kept their ancient Alexander Eaglerock biplane—nicknamed “The Flying Hobo”—operational through 21 days of challenging flight.

Allen wasn’t just Banning’s mechanic; he was co-pilot and equal partner in their historic journey. When funds ran low, he performed mechanical work at each stop to earn money for food and fuel.

Despite his crucial role, history often overlooks his contribution. The pair’s achievement required not just piloting skills but Allen’s ability to improvise repairs with limited resources while facing racial hostility across America’s airfields.

8. Willa Brown: The Aviator Who Trained the Airmen

Willa Brown shattered multiple ceilings as the first African American woman to earn both a pilot’s license and a commercial license in the United States. Her achievements extended beyond personal milestones—she became a pivotal figure in training the pilots who would later become the legendary Tuskegee Airmen.

As co-founder of the Coffey School of Aeronautics in Chicago, Brown created a pipeline for Black pilots when military aviation remained segregated. Her advocacy reached Washington, where she lobbied Congress to integrate the U.S. Army Air Corps.

Brown’s political engagement extended to becoming the first African American officer in the Civil Air Patrol. Her life embodied her belief that “the air is the only place free from prejudice.”

9. Cornelius Coffey: The Educator Who Built Aviation’s Foundation

When Chicago’s mechanics schools refused to admit Black students, Cornelius Coffey sued them—and won. This determination characterized his entire career as he became the first African American to hold both mechanic and pilot licenses simultaneously.

Coffey’s greatest legacy was educational. The school he founded with Willa Brown in 1938 trained hundreds of Black pilots and mechanics, many of whom later joined the Tuskegee Airmen. His innovative teaching methods revolutionized aircraft maintenance training for all students.

For over 50 years, Coffey remained active in aviation, developing specialized courses and mentoring generations of Black aviators. Chicago honored him by naming the Coffey School of Aeronautics after him—the first such recognition for an African American aviator.

10. John C. Robinson: From Mississippi to Ethiopia’s Skies

Born in segregated Mississippi, John Robinson’s journey to becoming known as the “Brown Condor” and father of Ethiopia’s air force seems almost mythical. After training in Chicago, he answered Ethiopia’s call for assistance against Italian invasion in 1935.

Robinson organized Ethiopia’s first air force with just a few planes against Mussolini’s modern air fleet. His service represented more than military aid—it symbolized Pan-African solidarity against European colonialism.

Upon returning to America, Robinson faced the irony of being celebrated internationally while still facing discrimination at home. Nevertheless, he continued training Black pilots and advocating for integration in aviation until his death in a plane crash in 1954.

11. Marie Dickerson Coker: Breaking Boundaries Beyond the Cockpit

Though not widely recognized today, Marie Dickerson Coker pioneered multiple aviation fields for Black women. Beyond her daring parachute jumps that thrilled 1930s crowds, she became one of the first Black women to earn a commercial pilot’s license.

Coker’s versatility extended to Hollywood, where she performed as a stunt pilot and actor. When World War II began, she applied to join the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) but was rejected due to her race, despite her extensive qualifications.

Undeterred, she joined the Civil Air Patrol and continued advocating for Black women in aviation. Her persistence helped dismantle the dual barriers of racism and sexism that had previously limited African American women’s participation in flight.

12. Chauncey Spencer: The Lobbyist Who Changed Military Aviation

Chauncey Spencer understood that changing aviation policy required political action. In 1939, he and Dale White flew a rented plane from Chicago to Washington, D.C. specifically to demonstrate Black pilots’ capabilities to skeptical lawmakers.

Their flight caught the attention of then-Senator Harry S. Truman, who famously remarked, “I didn’t know Negroes could fly airplanes.” After witnessing their skills, Truman supported including Black cadets in the Civilian Pilot Training Program—a crucial step toward the Tuskegee Airmen program.

Spencer’s advocacy wasn’t just about flying; it was about citizenship. He believed that if African Americans were expected to serve in wartime, they deserved equal opportunities in all aspects of military service, including aviation.

13. Janet Harmon Bragg: Investing in Aviation’s Future

When flight schools rejected her applications, Janet Harmon Bragg helped build one. Using her salary as a nurse, she invested in the Challenger Air Pilots Association, which purchased land and built an airfield outside Chicago specifically for training Black pilots.

Bragg’s determination was legendary. After being denied a commercial license in Chicago due to her race, she simply traveled to another testing center and passed with flying colors, becoming one of the first Black women to earn a commercial pilot’s license.

“You have to fight for what you want and what you believe in,” she often said. During World War II, she applied to join the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots but was rejected because of her race.

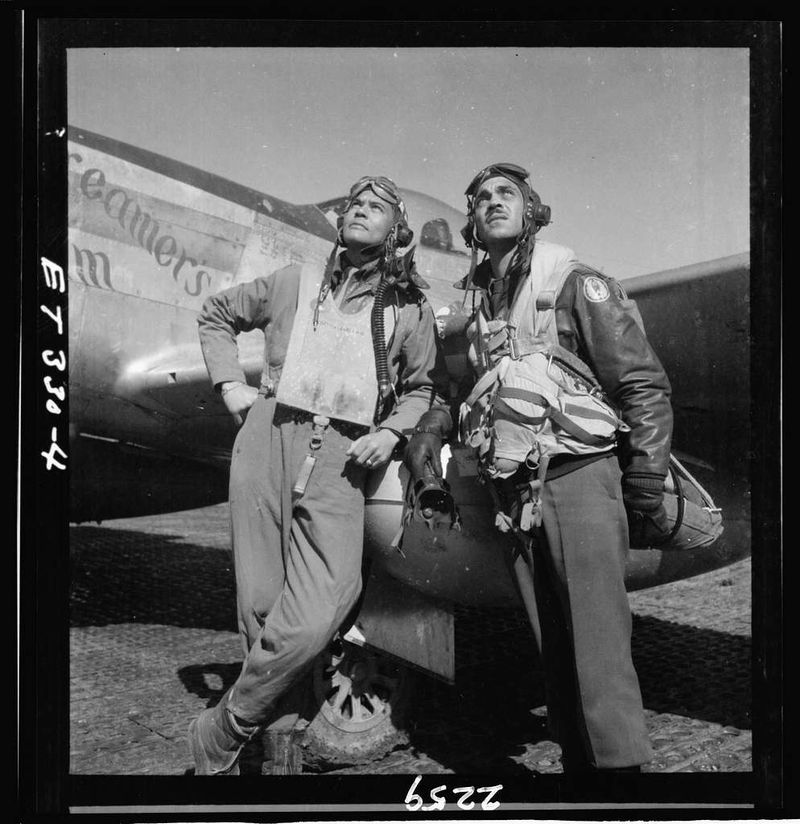

14. Edward C. Gleed: From Civilian Skies to Military Leadership

Before the Tuskegee program even existed, Edward Gleed was already challenging aviation’s color barriers. His early civilian flight training prepared him to become one of the first Black military pilots when the opportunity finally arose.

Rising through the ranks, Gleed eventually commanded the 332nd Fighter Group’s 301st Squadron. Fellow pilots respected his calm leadership under fire and his exceptional navigation skills that brought many pilots home safely from dangerous missions over Europe.

After completing 132 combat missions, Gleed continued his military career and advocated for full integration of the armed forces. His progression from civilian enthusiast to combat commander demonstrated the artificial nature of barriers that had kept Black pilots from military service.

15. Alfred Anderson: The Instructor Who Impressed a First Lady

As chief flight instructor at Tuskegee, Alfred “Chief” Anderson literally held the future of Black military aviation in his hands. His flying skills were so renowned that when Eleanor Roosevelt visited in 1941, she requested a flight with him despite Secret Service concerns.

That 30-minute flight changed history. Afterward, Mrs. Roosevelt famously declared, “I can go up with this young man anytime” and used her influence to support the Tuskegee program against military officials who wanted it terminated.

Anderson had earned his pilot’s license in 1929, paying for lessons with money from his job as a steel mill worker. By the war’s end, he had trained nearly 1,000 Black pilots who went on to distinguished military careers, forever changing American aviation.