American history textbooks often gloss over the harsh realities faced by enslaved people on Southern plantations.

Beyond the well-known horrors of slavery lie lesser-discussed aspects of daily life that reveal both the cruelty of the system and the remarkable resilience of those trapped within it.

These hidden truths paint a more complete picture of how enslaved individuals navigated their circumstances, preserved their humanity, and resisted oppression in ways both subtle and bold.

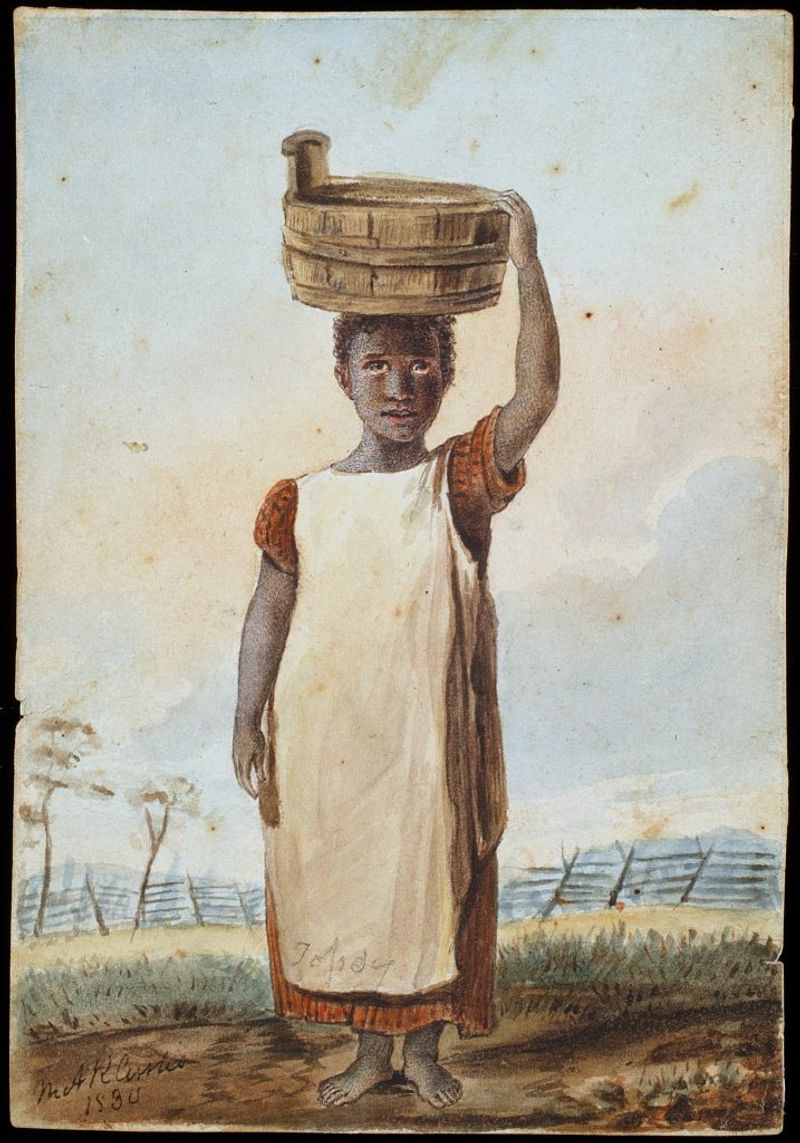

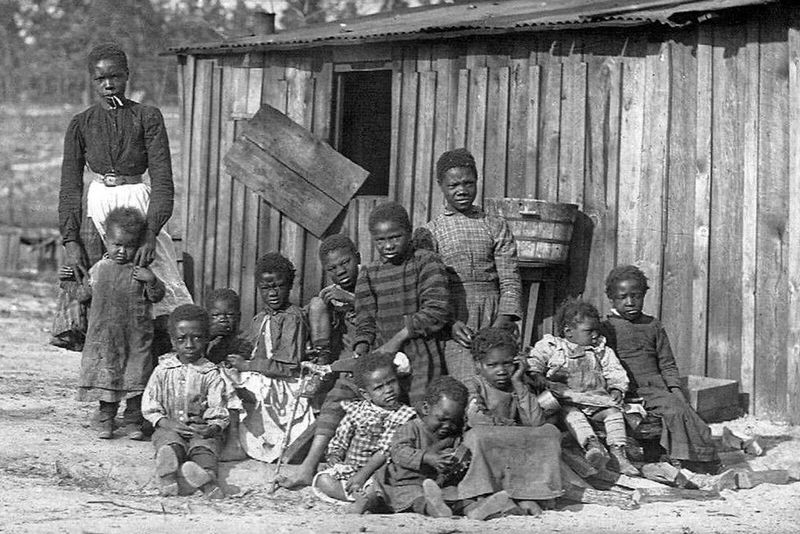

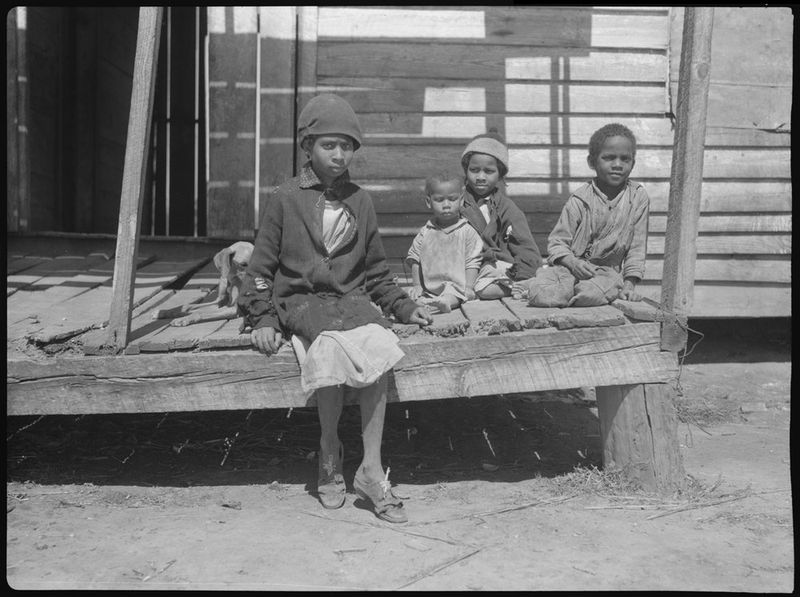

1. Enslaved Children Began Working As Young As 5

Childhood ended almost before it began for enslaved children on Southern plantations. By age 5, little ones were already assigned tasks like shooing birds from crops, fetching water, or carrying messages between fields.

As they grew older, responsibilities increased dramatically. Eight-year-olds might find themselves weeding cotton rows for hours, while pre-teens often performed nearly all adult labor.

This early introduction to forced labor wasn’t just about productivity—it was a deliberate system of conditioning. Children learned early that their bodies weren’t their own, setting the foundation for lifetimes of exploitation that benefited the plantation economy.

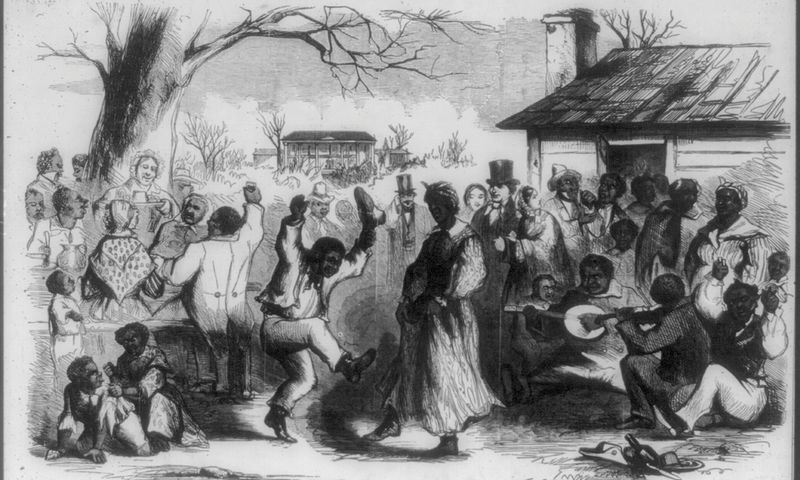

2. Sundays Were “Days Off” — But Rarely Restful

The myth of Sunday rest barely masked the reality of continued labor. While field work paused, enslaved people spent these supposed ‘free days’ washing clothes in heavy iron pots, mending worn garments, or tending personal garden plots that supplemented meager rations.

Many enslavers required church attendance, using Christianity as a control mechanism rather than spiritual comfort. Services often emphasized obedience to masters rather than liberation theology.

For some, however, Sundays offered rare moments of community building. Families separated across plantations might receive permission to visit, creating precious hours where children could know their parents and couples could briefly live as families before Monday’s bell signaled return to bondage.

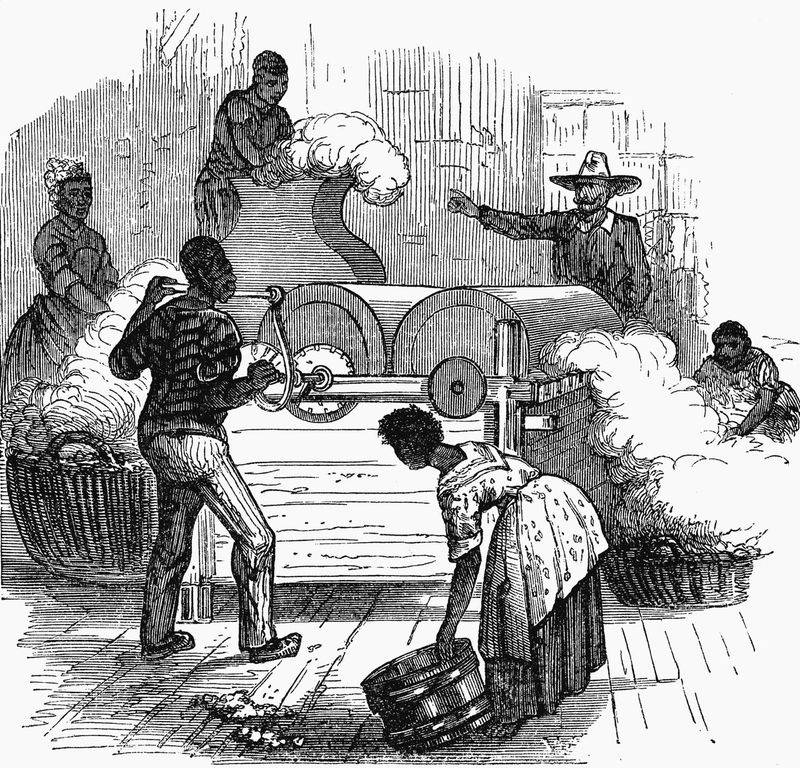

3. Night Work Was Common — And Brutal

Sunset didn’t signal rest for enslaved people. After enduring backbreaking field labor from dawn until dusk, their “personal time” became yet another opportunity for exploitation.

Women spun thread, wove cloth, and mended garments by dim candlelight that strained already exhausted eyes. Men processed harvested crops, repaired tools, or constructed buildings. During harvest seasons, entire communities worked through the night processing sugar cane or cotton, sometimes going days without proper sleep.

This relentless schedule served two purposes: maximizing profit from every moment of enslaved labor and preventing rest that might allow for planning resistance. Physical exhaustion became another form of control in an already brutal system.

4. “House Slaves” Weren’t Better Off

Working inside the big house offered different hardships, not relief. Enslaved domestic workers faced constant scrutiny, with every movement, expression, and word monitored for signs of insubordination.

Privacy never existed. Many slept on kitchen floors or hallways, available at all hours for the enslaver’s demands. Women especially faced heightened vulnerability to sexual violence, with nowhere to hide from predatory owners or their sons.

The psychological burden proved uniquely crushing. Required to maintain pleasant demeanors while witnessing family separations at auction blocks, house workers performed emotional labor alongside physical tasks. The supposed “privilege” of house work actually meant trading one form of brutality for another, equally devastating kind.

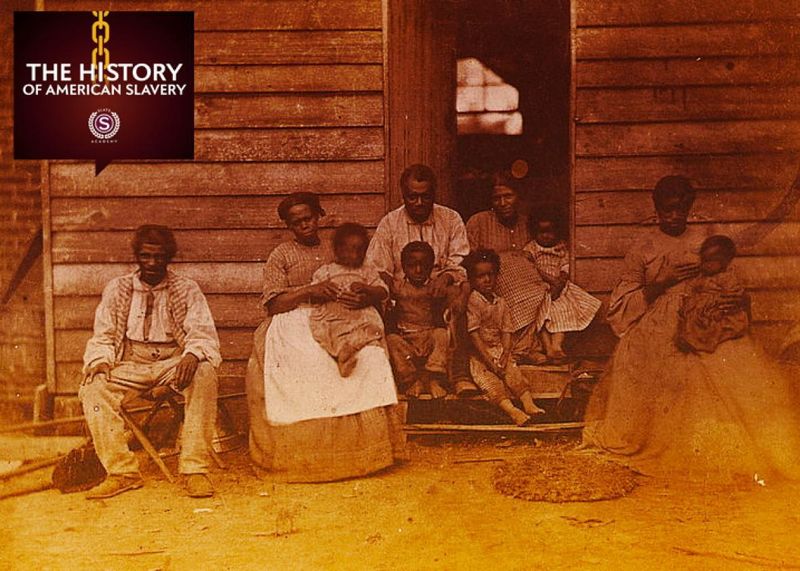

5. Marriage Was Encouraged — But Not Respected

Plantation owners often promoted marriage among enslaved people, not from moral concern but calculated self-interest. Married couples potentially produced children who became additional property, increasing the owner’s wealth.

These unions held no legal standing. “Jumping the broom” ceremonies created meaningful personal commitments, but enslavers disregarded these bonds whenever profitable. Husbands and wives lived with the constant knowledge that sale could separate them forever, sometimes with just hours’ notice.

Despite this precarious reality, enslaved couples created profound relationships. They exchanged handmade tokens as wedding symbols, adopted naming patterns to maintain family connections across plantations, and sometimes risked severe punishment to visit separated spouses—powerful testimony to human connection flourishing against impossible odds.

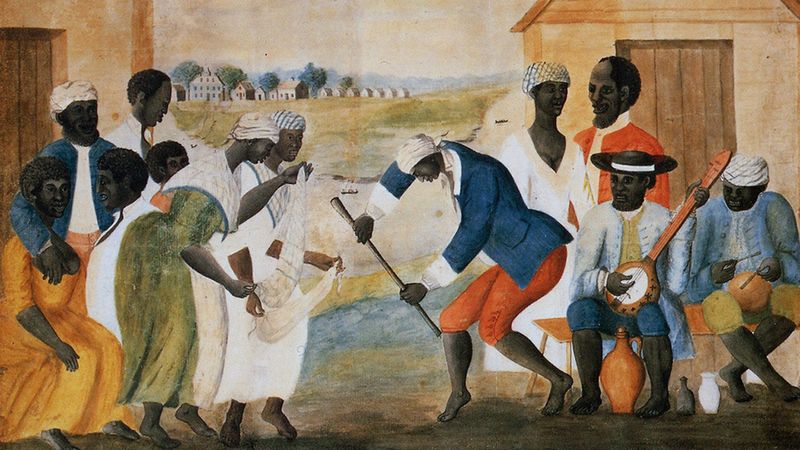

6. Resistance Was Woven into Daily Life

Far from accepting their circumstances, enslaved people engaged in constant, creative resistance. Work slowdowns—breaking tools, pretending illness, or deliberately misunderstanding instructions—became silent weapons against exploitation.

Knowledge passed secretly between generations. Children learned which plants could induce temporary illness to avoid brutal field work. Women sharing recipes exchanged coded information about escape routes or unsympathetic overseers.

Music served as both psychological survival mechanism and resistance tool. Field songs contained hidden messages and preserved cultural memories forbidden by enslavers. Even maintaining African hairstyles or naming practices represented quiet rebellion against a system determined to erase identities—small but powerful assertions of humanity that undermined slavery’s dehumanizing foundation.

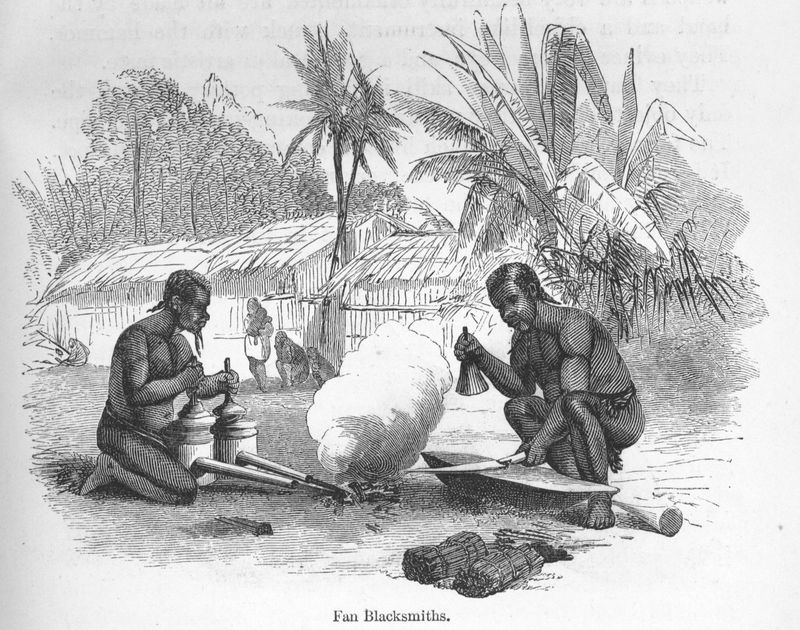

7. Skilled Labor Didn’t Mean Freedom

Blacksmiths crafted intricate ironwork adorning Charleston mansions. Carpenters created architectural masterpieces their descendants couldn’t enter. Master seamstresses designed gowns for debutantes who wouldn’t acknowledge their humanity.

Enslaved artisans possessed extraordinary talents but remained property. Their skills often increased their monetary value, making escape more difficult as owners placed greater restrictions on their movements.

Some skilled workers negotiated limited privileges—occasionally hiring out their time and keeping small portions of earnings. Yet these arrangements remained tenuous. An enslaver’s financial troubles could instantly result in skilled craftspeople being sold away from families. Their expertise built the South’s wealth and beauty while they themselves remained unable to benefit from their own remarkable abilities.

8. Religion Was a Double-Edged Sword

Sunday sermons on plantations often emphasized passages like “Slaves, obey your earthly masters.” Enslavers wielded Christianity as justification for bondage, claiming a divine mandate for the existing racial hierarchy.

Behind closed doors, however, enslaved communities transformed religion into something entirely different. In secret “hush harbors” deep in woods beyond overseer surveillance, they developed theology emphasizing liberation, dignity, and divine justice. Biblical stories of exodus became powerful metaphors for their own hoped-for deliverance.

African spiritual traditions survived despite suppression, sometimes blending with Christianity into unique practices. Ring shouts, spiritual possession, and ancestor veneration continued, preserving connections to cultures enslavers tried to erase. Faith became simultaneously a tool of oppression and a wellspring of resistance.

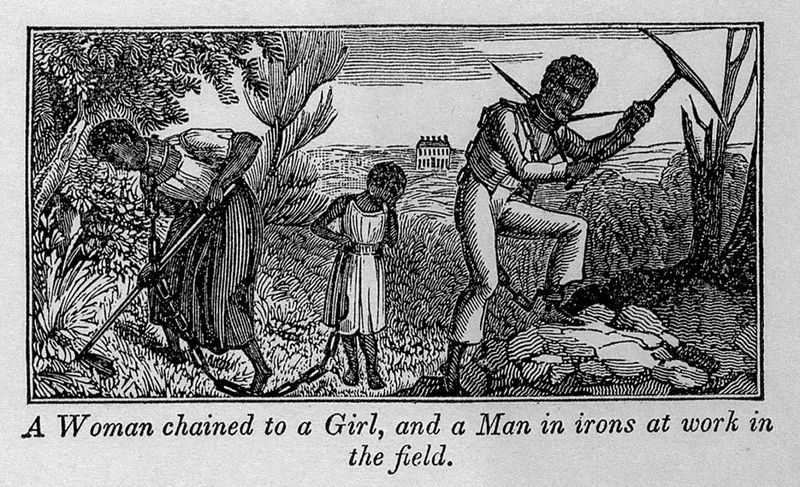

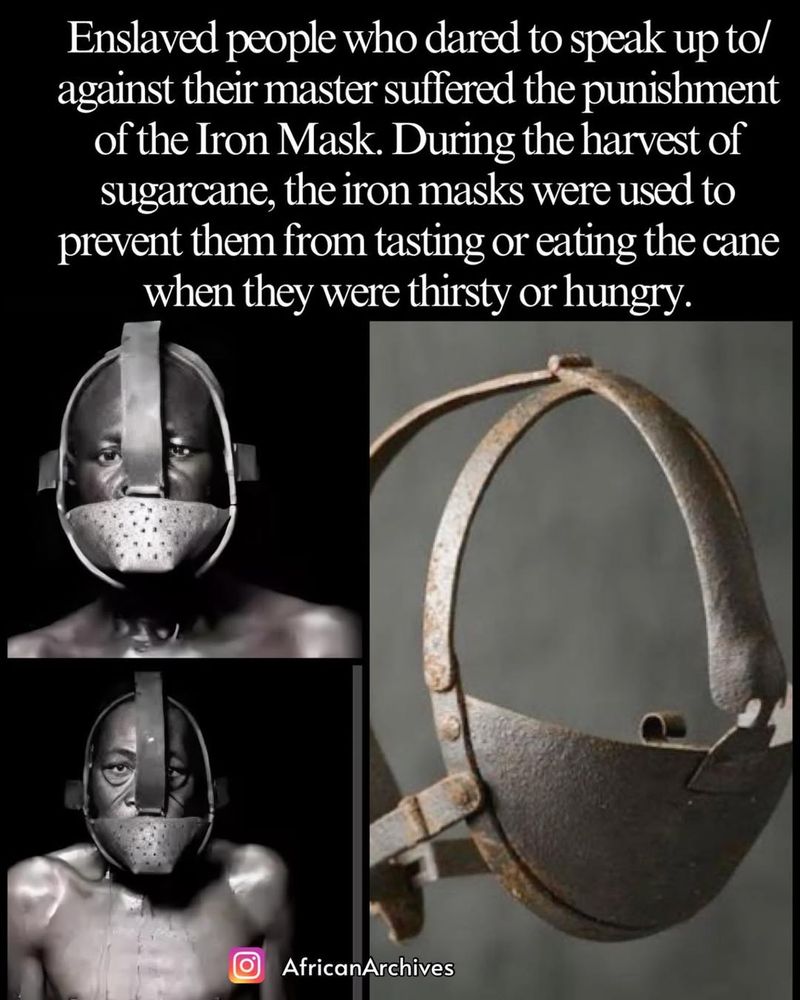

9. Whippings Weren’t the Worst Punishments

Public whippings served as theatrical demonstrations of power, but enslavers employed far more sinister punishments beyond the lash. Iron masks with tongue suppressors prevented eating or drinking while forcing silence. Ankle chains with bells announced every movement, denying even momentary privacy.

Particularly sadistic owners used “sweat boxes”—small metal containers that became scorching in summer heat, causing extreme dehydration and sometimes death. Others employed psychological torture through family separation or forcing enslaved people to whip their own loved ones.

These sophisticated cruelties served a calculated purpose beyond immediate pain. They created psychological terror throughout enslaved communities, demonstrating the complete control enslavers held over bodies and relationships. The scars from such experiences lasted generations, embedding trauma in family histories.

10. Language and Culture Were Erased — Then Rebuilt

Enslavers deliberately separated people sharing common languages upon arrival from Africa, attempting to prevent communication that might foster rebellion. Native tongues became dangerous to speak openly, risking severe punishment.

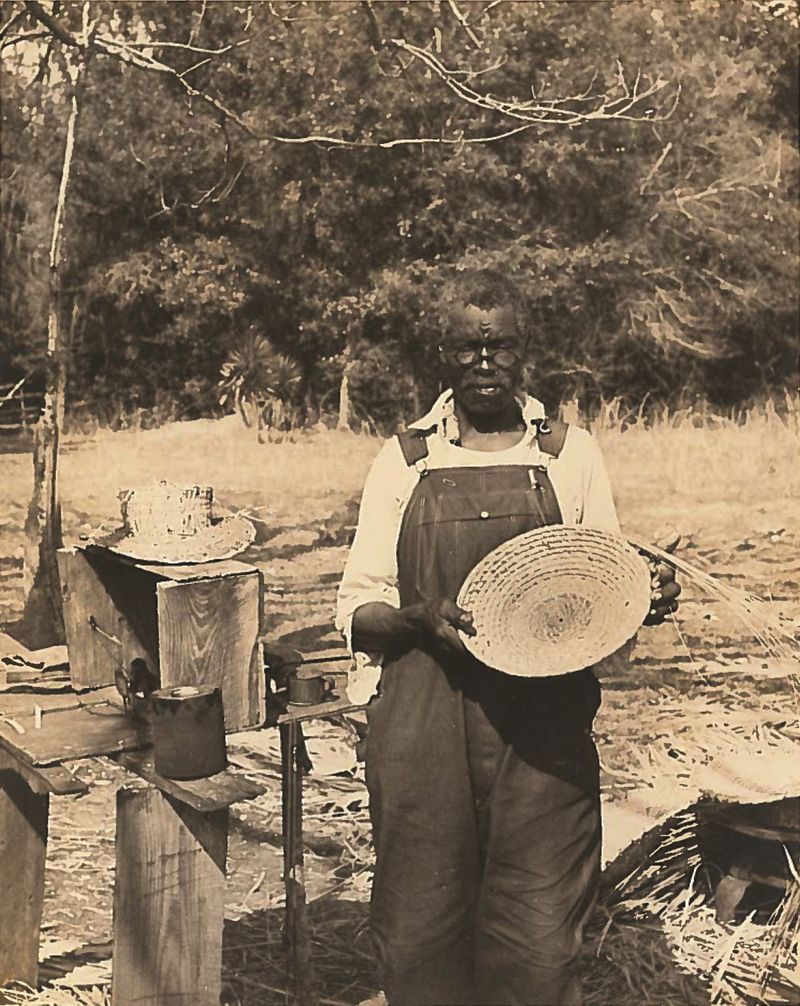

Remarkably, cultural erasure failed. Enslaved communities developed Creole languages like Gullah-Geechee that preserved African linguistic patterns while incorporating English vocabulary. Stories, songs, and proverbs maintained ancestral wisdom through coded meanings enslavers couldn’t decipher.

Material culture similarly evolved through necessity and resistance. Basket weaving techniques from specific African regions survived in sweetgrass baskets still created today. Cooking methods, musical instruments, and agricultural practices maintained cultural connections across generations despite systematic attempts to destroy these links to identity and heritage.

11. Pregnancy Didn’t Protect Women from Labor

Expectant mothers received no respite from grueling fieldwork. Heavy with child, women continued picking cotton, hoeing rows, and hauling water until labor began—sometimes giving birth right in the fields before returning to work.

Postpartum recovery proved nonexistent. New mothers often resumed full labor duties within days of delivery, carrying infants to field edges where older children watched them. Breast-feeding happened during brief breaks, with women rushing between crop rows and crying babies.

This brutal treatment reflected enslaved women’s dual exploitation: as both laborers and reproductive assets. Their children represented financial gain for enslavers, yet this didn’t merit maternal care or protection. The resulting physical toll—prolapsed uteruses, chronic pain, and high maternal mortality—represents one of slavery’s most devastating physical legacies.

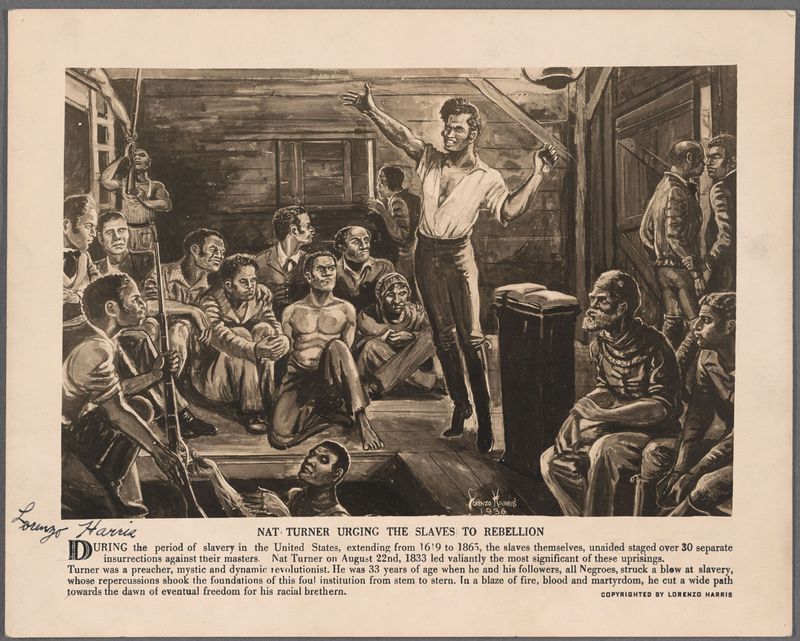

12. Some Enslaved People Fought Back — Violently

History records over 250 documented rebellions across the American South. Nat Turner’s 1831 uprising left approximately 60 white Virginians dead before being brutally suppressed. Denmark Vesey organized thousands in Charleston before betrayal exposed his plans.

These armed resistances required extraordinary courage. Participants knew failure meant execution, often preceded by torture. Yet they risked everything, preferring death fighting oppression to living under it.

Less dramatic but equally significant violent resistance occurred daily. Enslavers were poisoned by household cooks, barns mysteriously burned, and particularly brutal overseers sometimes disappeared. Southern newspapers rarely reported these incidents, fearing they would inspire others. White Southern society’s obsession with security and armed patrols reveals their constant fear of those they oppressed—recognition that bondage never meant acceptance.

13. Informal Education Was Dangerous but Real

Laws throughout the South criminalized teaching enslaved people to read or write. Penalties included whipping, branding, and amputation of fingers. These harsh punishments revealed how threatening literacy appeared to the slavery system.

Despite dangers, learning flourished in secret. Children traced letters in dirt, quickly erasing evidence. Adults memorized Bible passages heard at church, later matching symbols to memorized words. Some enslavers’ children secretly taught playmates, while others learned through observation while serving in houses.

Frederick Douglass famously wrote that learning to read opened his mind to freedom’s possibility. Literacy enabled forged travel passes, communication between separated families, and access to abolitionist ideas. Those who risked everything for education understood knowledge was power—perhaps the most dangerous kind in a system built on enforced ignorance.

14. Food Was Scarce and Monotonous

Weekly rations typically consisted of a few pounds of cornmeal, small portions of salt pork (often rancid), and occasional molasses. This diet—deficient in vital nutrients—caused widespread pellagra, rickets, and night blindness among enslaved communities.

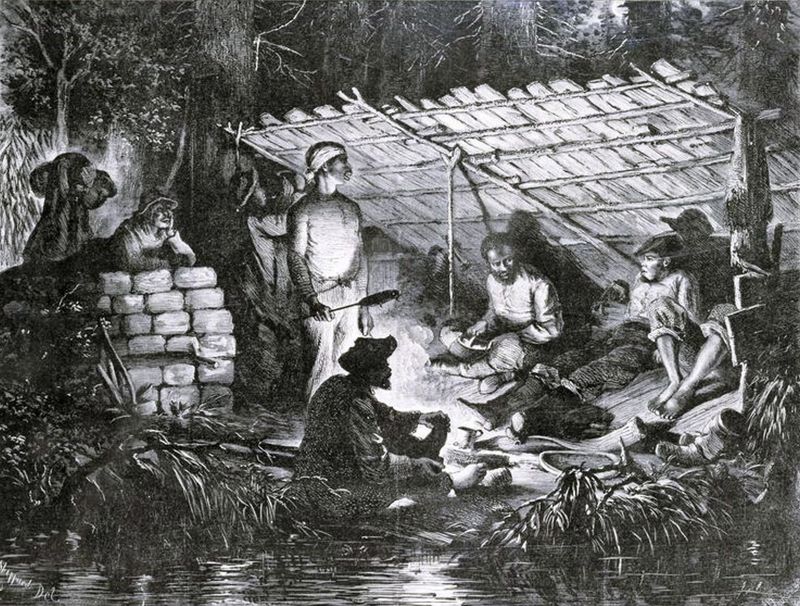

Resourcefulness became essential for survival. Secret gardens hidden in forest clearings grew vegetables beyond overseer inspection. Fishing and trapping supplemented protein when possible, though being caught with unauthorized food could result in severe punishment.

Cooking traditions transformed these meager ingredients into nourishing meals that later became Southern cuisine staples. Women developed one-pot stews that could simmer while working, preserving techniques for vegetables, and methods of making tough meat edible. These culinary innovations represented both physical survival strategy and preservation of cultural heritage against deliberate deprivation.

15. Motherhood Was Filled With Fear

Bringing a child into enslavement meant embracing heartbreak as possibility. Mothers nursed babies knowing they might be sold at any moment—sometimes directly from their arms when plantation owners faced financial difficulties.

This reality created agonizing dilemmas. Some mothers attempted to seem less attached to their children, hoping to prevent separated sale. Others deliberately taught children independence skills from earliest ages, preparing them for possible life alone.

Names became vessels for preserving family connections despite separation. Children received grandparents’ names or distinctive patterns that identified their lineage if encountered on different plantations years later. These naming practices represent one of many ways enslaved mothers created systems to maintain family bonds against a system designed specifically to sever them.

16. Escape Routes Were Everywhere — and Nowhere

Freedom seekers employed countless methods beyond the Underground Railroad. Some disappeared into dense swamplands like the Great Dismal Swamp, forming maroon communities that survived for generations. Others escaped to Spanish Florida before American acquisition, where different legal systems offered potential freedom.

Urban enslaved people sometimes “passed” as free through forged documents, particularly those with lighter complexions due to forced sexual relationships between enslavers and the enslaved. Some stowed away on Northern-bound ships, hiding for weeks in cargo holds.

These escapes required extraordinary courage. Bloodhounds tracked scents for miles, professional slave catchers earned substantial rewards, and capture meant brutal punishment. Yet thousands risked everything for freedom, undermining Southern propaganda that enslaved people were content with their condition.

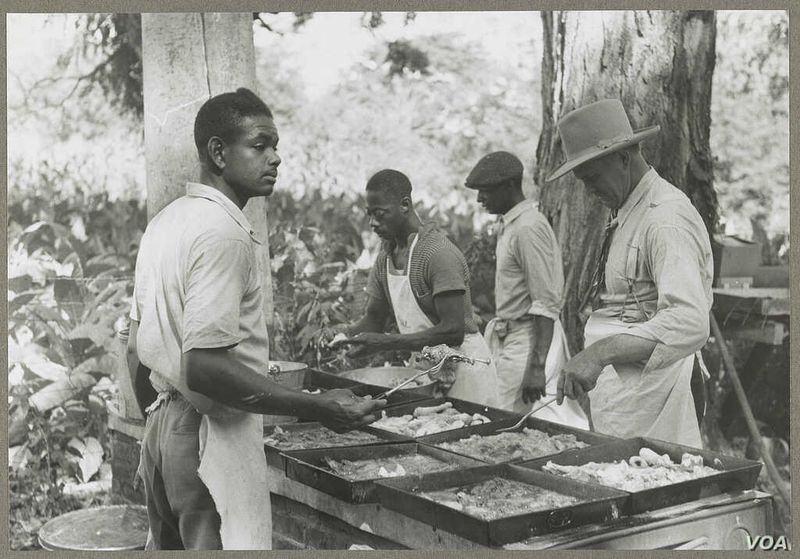

17. Enslaved People Shaped American Cuisine

Southern food traditions owe their existence largely to enslaved African cooks who transformed regional cuisine. Rice cultivation techniques from West Africa established the Carolina rice economy, while okra, black-eyed peas, and watermelon arrived with enslaved Africans.

Barbecue’s low-and-slow cooking method developed from enslaved cooks who received the least desirable meat cuts, creating techniques to render tough portions delicious. Gumbo’s name derives from the Bantu word for okra, revealing its direct African lineage.

Beyond ingredients, cooking methods like deep-frying, one-pot stewing, and preservation techniques stemmed from enslaved communities’ culinary knowledge. The irony remains that dishes created under brutal circumstances became celebrated American cuisine, often without acknowledgment of their origins in the creativity and resilience of those who developed them while denied their freedom.

18. Emancipation Didn’t End Their Struggles

Freedom arrived with the Thirteenth Amendment, but exploitation quickly found new forms. Convict leasing systems arrested Black Americans on minor charges like “vagrancy,” then rented them to former plantation owners as prison labor under conditions often worse than slavery.

Sharecropping trapped families in perpetual debt cycles. Former enslavers, now landlords, controlled crop prices, inflated supply costs, and manipulated accounting, ensuring workers never accumulated enough to purchase land or move elsewhere.

Violence enforced this new economic subjugation. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan, widespread lynching, and legally sanctioned segregation created a climate of terror designed to prevent Black economic advancement or political participation. The end of legal enslavement marked not freedom’s arrival but the beginning of new struggles that would continue through generations.