Behind the quiet pages of books, small groups of readers have shaped the course of human events.

Book clubs aren’t just social gatherings – they’ve launched revolutions, preserved forbidden knowledge, and sparked movements that changed societies forever.

These literary circles operated with little fanfare, yet their discussions rippled outward with remarkable consequences.

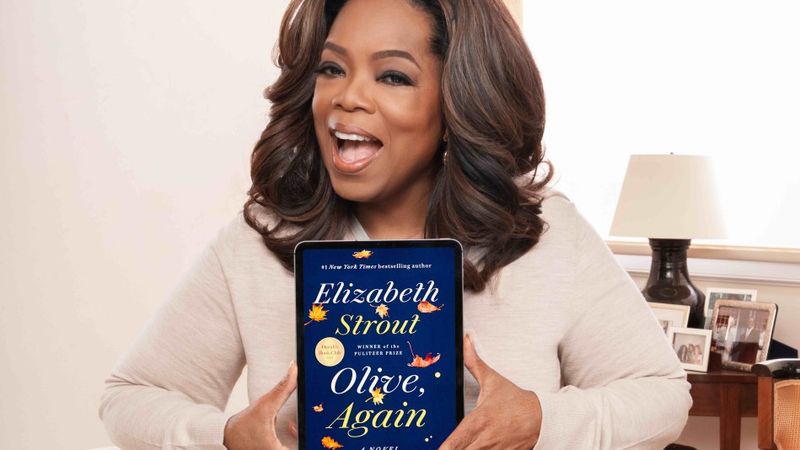

1. Oprah’s Book Club

Mention Oprah Winfrey’s Book Club to any publisher and watch their eyes light up. Since 1996, this cultural juggernaut has transformed obscure titles into instant bestsellers, sometimes selling millions of additional copies overnight.

Authors lucky enough to receive Oprah’s golden seal found themselves catapulted from literary obscurity to household names. More importantly, the club tackled difficult subjects – addiction, abuse, racism – bringing conversations usually confined to academic circles into America’s living rooms.

The club’s real power? Making serious literature accessible to everyday readers who might never have picked up these challenging works otherwise.

2. The Bloomsbury Group

Meeting in London’s Bloomsbury district in the early 20th century, this wasn’t just a book club – it was an intellectual revolution. Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster, John Maynard Keynes, and others gathered in living rooms to challenge Victorian conventions about everything from sexuality to art.

Their radical ideas about feminism, pacifism, and aesthetic theory flowed from these intimate gatherings into novels, economic theories, and paintings that defined modernism. They lived by their own rules too – pursuing open marriages and same-sex relationships decades before such arrangements were socially acceptable.

Without their boundary-pushing conversations, literature might have taken decades longer to embrace stream-of-consciousness and psychological realism.

3. The Inklings

Picture this: A smoky corner of an Oxford pub called The Eagle and Child. A group of tweedy professors huddle around pints of ale while one reads aloud from handwritten pages about hobbits or talking lions. The others interrupt with suggestions, criticisms, and encouragement.

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien formed the core of this extraordinary writing group that met regularly between the 1930s and 1950s. Middle-earth and Narnia were born in these meetings, shaped by friendly but rigorous peer review.

Fantasy literature as we know it today – with its fully realized worlds and moral complexity – emerged directly from these Thursday evening gatherings that blended scholarship, mythology, and Christian theology.

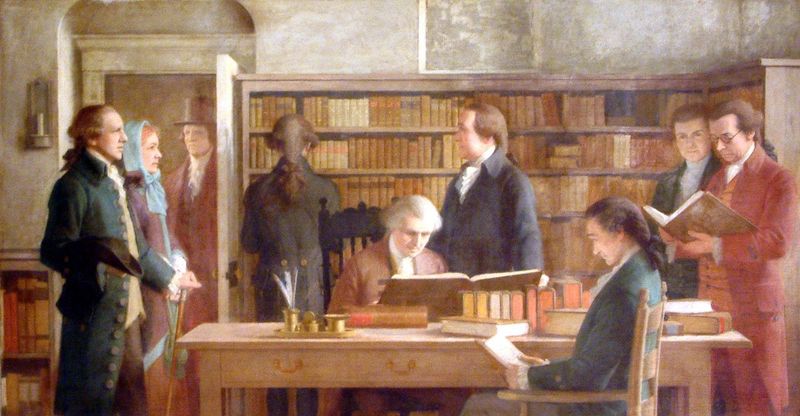

4. Franklin’s Junto

Long before book clubs became associated with wine and casual chatter, Benjamin Franklin created something far more ambitious. In 1727, the 21-year-old Franklin invited twelve friends to form a club for mutual improvement in Philadelphia.

Members brought books to share and discuss specific questions about morals, politics, and natural philosophy. They debated topics from “Does a perfect government exist?” to practical matters of business ethics. This wasn’t just talk – the Junto spawned America’s first lending library, volunteer fire department, and even influenced the University of Pennsylvania’s founding.

Franklin’s little reading group became the laboratory where democratic values were tested and refined before the American Revolution.

5. The Harlem Renaissance Reading Circles

Cramped apartments in 1920s Harlem became electric forums where Black writers shared works that mainstream publishers initially rejected. Langston Hughes first read his jazz-influenced poems at these gatherings, while Zora Neale Hurston tested out folklore-inspired tales before supportive but critical peers.

These weren’t formal clubs with membership cards – they were fluid networks connecting artists, intellectuals, and patrons across racial lines. What made these circles revolutionary was their rejection of the idea that Black art should primarily serve as protest or propaganda.

Instead, they championed artistic expression that captured the full spectrum of African American experiences, creating space for Black joy and complexity in American literature for the first time.

6. Eleanor Roosevelt’s Book Club

When the First Lady of the United States recommends a book, people notice. Eleanor Roosevelt wielded this influence with extraordinary purpose during some of America’s darkest hours. Through her newspaper column “My Day” and radio broadcasts, she essentially created a nationwide book club focused on social justice.

Roosevelt highlighted works about poverty, racial inequality, and human rights when these topics were considered too controversial for polite conversation. She introduced Americans to Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and Richard Wright’s “Native Son” – books that forced comfortable readers to confront uncomfortable realities.

Her recommendations weren’t random – they strategically supported her husband’s New Deal policies while pushing public opinion toward greater compassion.

7. The Guerrilla Book Clubs of Apartheid-Era South Africa

In townships across South Africa, ordinary-looking gatherings disguised extraordinary acts of resistance. People risked imprisonment to share dog-eared copies of banned books smuggled through underground networks. Works by Steve Biko, Nelson Mandela, and international writers critical of apartheid passed from hand to hand.

Security forces regularly raided these meetings, yet the clubs persisted. Members often memorized passages to share orally when physical books weren’t available – reviving ancient storytelling traditions out of necessity.

These clandestine reading groups created informed citizens ready to lead when apartheid finally fell. Many club participants later became government officials, having developed their political philosophies through these forbidden discussions.

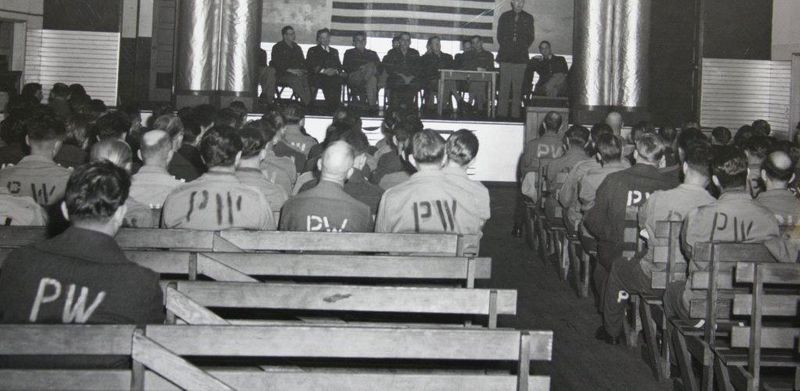

8. WWII Prisoner-of-War Camp Book Clubs

Barbed wire and armed guards couldn’t stop the human need for mental escape. In Nazi and Japanese POW camps, captured Allied soldiers formed reading circles around whatever books they could obtain through Red Cross packages or sympathetic guards.

A single copy of Dickens’ “Great Expectations” might be carefully disassembled so chapters could circulate among hundreds of prisoners. These literary discussions provided more than entertainment – they preserved sanity and hope when both were in desperately short supply.

Some camps even organized formal lectures and debates based on their reading, creating impromptu universities behind enemy lines. Many survivors later credited these intellectual lifelines with their psychological survival through years of captivity.

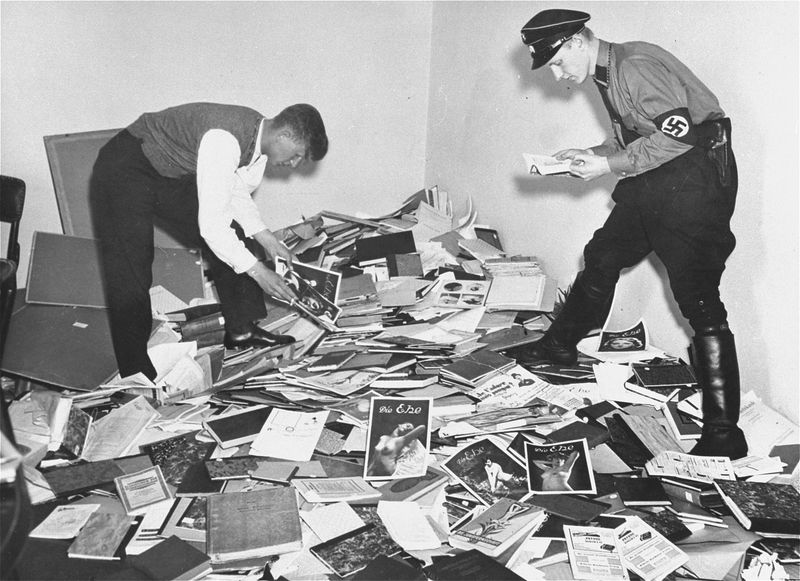

9. The Nazi-Banned Reader Circles

When Hitler’s bonfires consumed “un-German” books across the Reich, small acts of literary preservation became acts of tremendous courage. Ordinary Germans – professors, housewives, clergy – hid forbidden works by Jewish authors, political opponents, and modernist thinkers.

These secret reader circles met in basements and attics to discuss Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, and Heinrich Heine, keeping Germany’s humanist tradition alive when it was most threatened. Discovery meant arrest, concentration camps, or execution – yet participants considered the risk worthwhile.

After Germany’s defeat, these preserved books and the discussions around them provided cultural continuity that helped rebuild German intellectual life from the ashes of fascism.

10. The Black Panther Party’s Reading Groups

“Revolutionary education” meant something very specific in Black Panther Party chapters across America in the late 1960s. Members gathered not just to read Marx and Fanon but to apply these theories directly to their communities’ struggles.

These weren’t casual book discussions but disciplined study sessions where Panthers developed the intellectual framework for their free breakfast programs, community health clinics, and political campaigns. Young activists who might have received limited formal education became sophisticated political theorists through this collective learning approach.

FBI documents reveal how authorities feared these reading groups more than armed Panther patrols – recognizing that revolutionary ideas, once embedded in a community, can’t be stopped with arrests alone.

11. The Jane Austen Society

Started in 1940 while bombs fell on England, this seemingly quaint appreciation club had surprisingly radical underpinnings. Founded to preserve Austen’s home in Chawton, the society quickly became something more – a feminist reclamation project celebrating a woman writer long dismissed by the male literary establishment.

What began with a handful of devotees expanded into a global network that transformed Austen from a “minor novelist” into a recognized literary giant. Members funded scholarly research that revealed the sharp social critique beneath Austen’s marriage plots.

The society’s work directly challenged assumptions about “women’s writing” and helped establish female authors as worthy of serious academic study – changing university curricula worldwide.

12. Goodreads Groups

Who would have thought that a website could reinvent the ancient practice of communal reading? Since 2007, Goodreads has created virtual book clubs connecting readers across continents who would never meet in physical space.

The platform hosts thousands of specialized groups – from “Dystopian YA Fiction Fans” to “19th Century Russian Literature Lovers.” Their collective reviews and ratings now influence publishing decisions, book marketing campaigns, and even what authors choose to write next.

Most revolutionary is how these digital communities have democratized literary criticism. Ordinary readers, not just credentialed experts, now shape literary reputations through their aggregated opinions – sometimes elevating overlooked works that traditional gatekeepers dismissed.

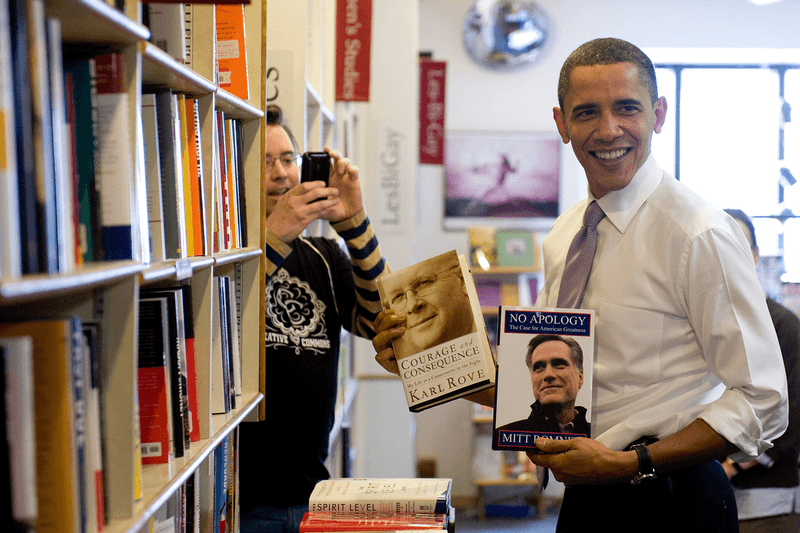

13. The Obama Reading List Fan Clubs

Barack Obama’s annual reading lists have spawned an unusual phenomenon – thousands of readers who faithfully tackle whatever the former president recommends. These informal clubs spread across social media platforms, creating unexpected bestsellers from obscure titles.

Obama’s selections typically highlight diverse voices – Nigerian novelists, LGBTQ memoirists, historians examining forgotten chapters of American experience. The resulting discussions have introduced many readers to perspectives they might never have encountered otherwise.

What makes this influence remarkable is how it operates outside traditional political channels. Even Americans who disagree with Obama’s politics often trust his literary judgment, creating rare common ground in a polarized culture.

14. The Transcendental Club

They called themselves the “Hedge Club” or “Symposium” – never actually using the term “Transcendentalists” that history would assign them. Meeting in Massachusetts homes during the 1830s-40s, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and others shared readings that reimagined humanity’s relationship with nature and divinity.

Their conversations synthesized European Romanticism, Eastern philosophy, and American individualism into something entirely new. From these fireside discussions emerged essays like “Self-Reliance” and books like “Walden” that would define American philosophical thought.

Perhaps most radical was their inclusion of women as intellectual equals, with Margaret Fuller’s feminist writings emerging directly from club debates that recognized her brilliant mind.

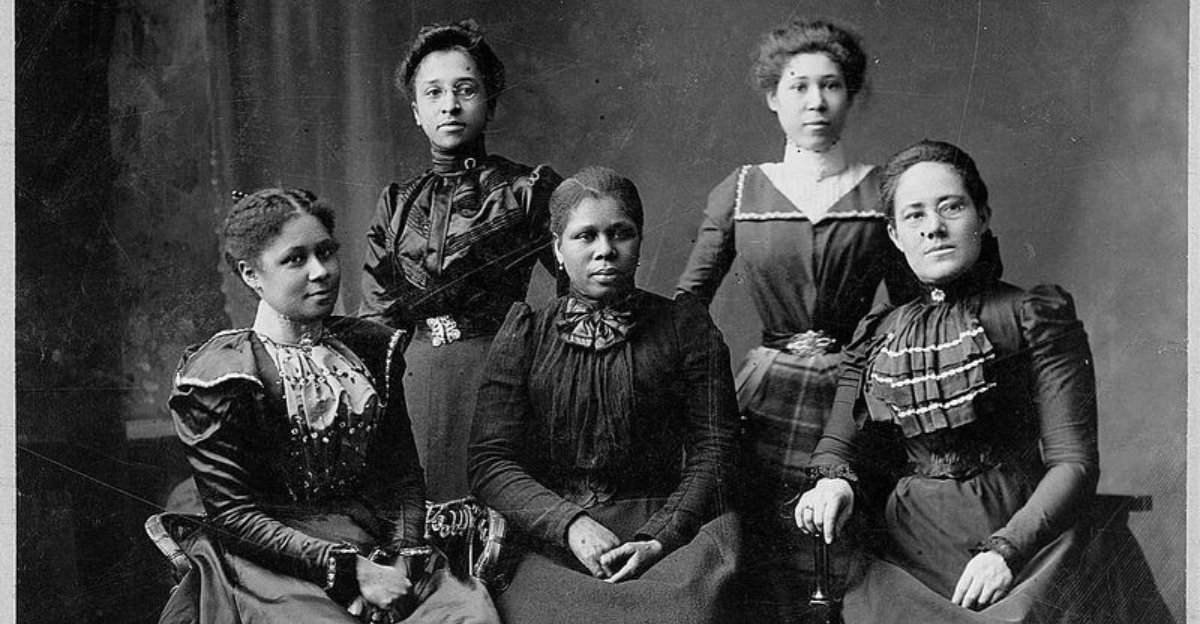

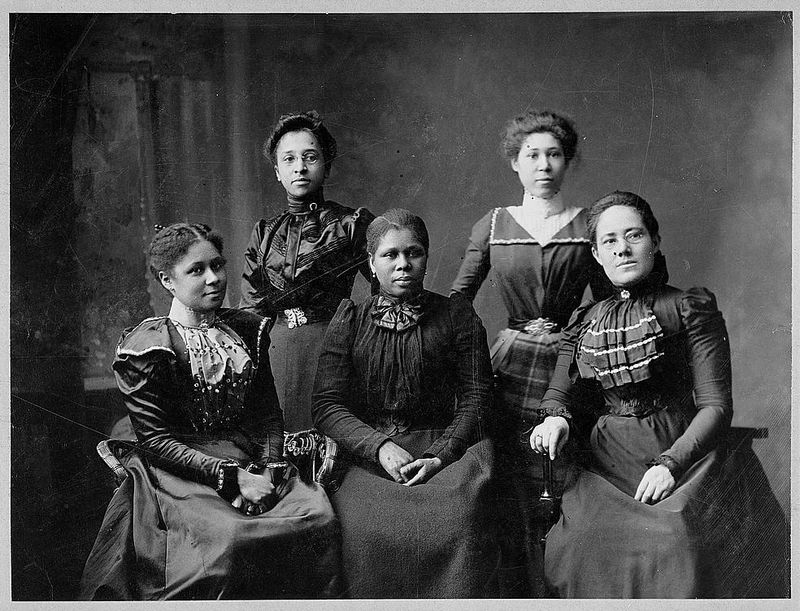

15. The Women’s Reading Clubs of the 19th Century

When higher education remained largely closed to them, American women created their own universities in living rooms across the country. Starting in the 1800s, these clubs followed serious study curricula despite being dismissed as frivolous “ladies’ gatherings” by male society.

Members tackled everything from classical literature to political economy, preparing papers and leading discussions with academic rigor. Knowledge gained in these intellectual spaces directly fueled women’s suffrage campaigns and progressive reform movements.

Club records reveal how these groups strategically maintained a non-threatening appearance while quietly building the first networks of politically engaged women who would eventually demand the vote and transform American society.

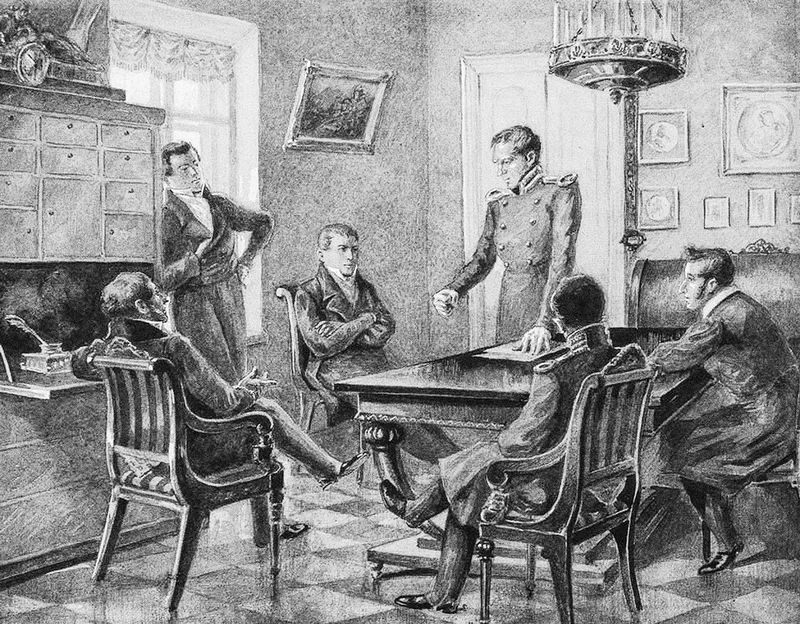

16. The Russian Decembrist Literary Circles

Before they attempted revolution in December 1825, young Russian aristocrats gathered in St. Petersburg salons for what appeared to be innocent literary discussions. These officer-poets read forbidden Western political works alongside Russian classics, developing radical ideas about constitutional government and abolishing serfdom.

Though their uprising failed and many were executed or exiled to Siberia, the literary circles that nurtured their revolutionary consciousness continued underground for decades. Their poetry and writings, often smuggled from prison, inspired generations of Russian dissidents.

The Decembrists established a uniquely Russian tradition where literature and politics remained inseparable – creating a model for intellectual resistance that continued through Soviet times to the present day.

17. The Algonquin Round Table

Not strictly a book club, but certainly a literary circle that changed American culture forever. From 1919 to roughly 1929, writers including Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, and Alexander Woollcott gathered daily at New York’s Algonquin Hotel for lunches that combined vicious wit with serious literary discussion.

Their rapid-fire banter created a new American writing style – sharp, concise, and conversational – that influenced everything from magazine journalism to screenwriting. Members founded The New Yorker magazine, wrote groundbreaking Broadway plays, and established the modern book review format.

Beyond their literary contributions, the Round Table normalized the idea of women as equal intellectual sparring partners in an era when female writers were often sidelined.