Rosa Parks sparked a revolution with a simple act of courage on a Montgomery bus in 1955. By refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger, this seamstress-turned-activist ignited the Civil Rights Movement and changed American history forever. Her quiet determination in the face of injustice shows how ordinary people can create extraordinary change.

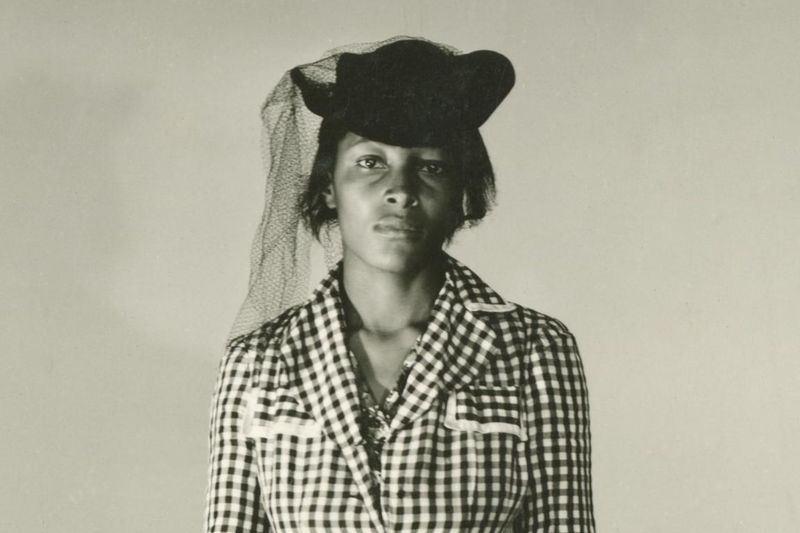

1. Alabama Beginnings

February 4, 1913 marked the birth of a civil rights giant in tiny Tuskegee, Alabama. Rosa Louise McCauley entered a world sharply divided by racial lines, where Jim Crow laws controlled every aspect of Black Americans’ lives. Her early years were shaped by the harsh realities of segregation – separate schools, restaurants, drinking fountains, and the constant threat of violence. These childhood experiences planted seeds of resistance that would later bloom into historic activism. Growing up under her mother and grandparents’ guidance, young Rosa learned to navigate a dangerous world while maintaining her dignity and self-respect.

2. Education Against All Odds

Despite segregated schools with limited resources, Rosa’s intelligence and determination shined brightly. Her mother, a former teacher, emphasized education’s importance even when circumstances forced Rosa to leave school temporarily at 16 to care for ailing family members. Against tremendous odds, she returned to complete her high school education in 1933 – a remarkable achievement when less than 7% of Black Americans had high school diplomas. The Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, founded by northern liberals specifically for Black students, provided Rosa with rare educational opportunities. These formative years shaped her belief that knowledge was power in the fight against injustice.

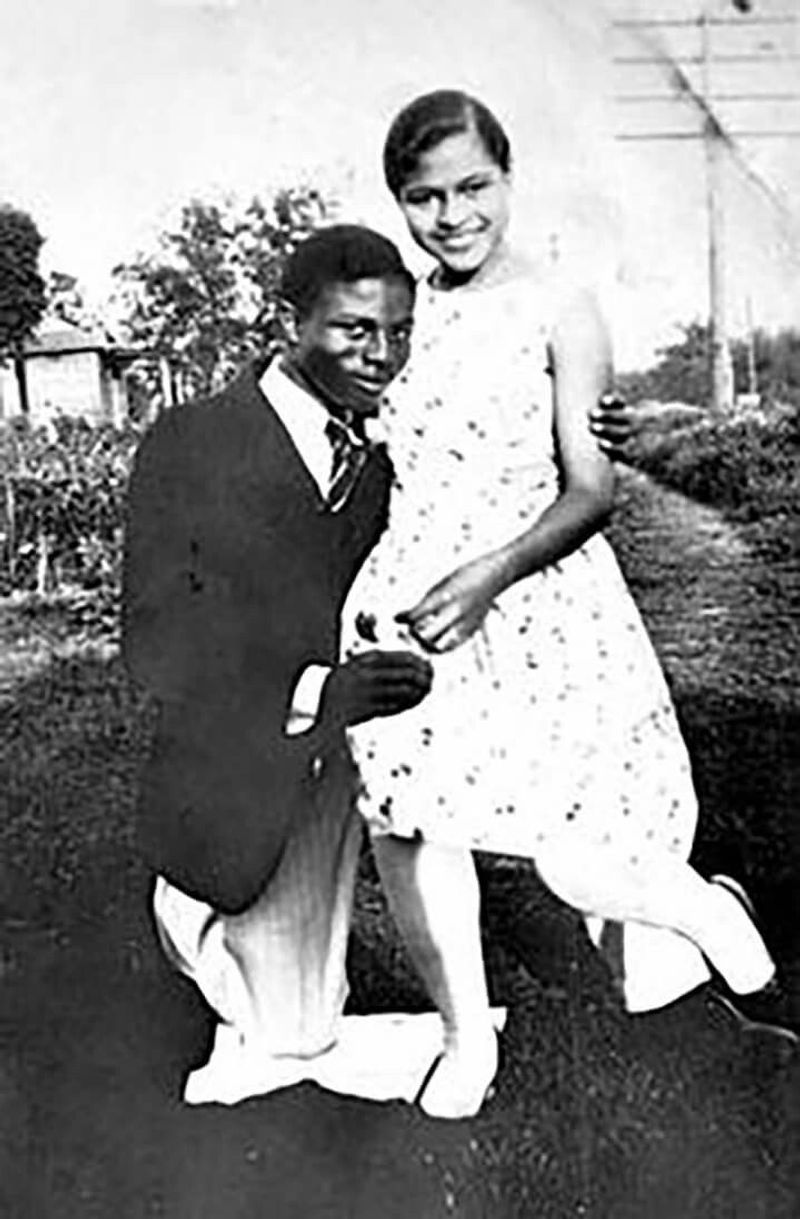

3. Marriage to a Fellow Activist

Raymond Parks wasn’t just Rosa’s husband – he was her partner in resistance. Their 1932 marriage united two souls committed to challenging racial injustice. Raymond, a barber by trade, was already an NAACP member actively working on behalf of the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers falsely accused of rape. His fearlessness inspired Rosa. Though soft-spoken, Raymond possessed remarkable courage, attending civil rights meetings despite the very real threat of violence against Black men who dared challenge the status quo. Together, they created a home that became a safe harbor for discussing dangerous ideas about equality and justice.

4. Becoming NAACP Secretary

The year 1943 marked Rosa’s official entry into organized civil rights work. E.D. Nixon, president of the Montgomery NAACP chapter, recognized her meticulous attention to detail and unwavering commitment, appointing her chapter secretary. Far from a ceremonial role, this position placed Rosa at the heart of the movement. She documented cases of discrimination, collected membership dues, and coordinated communications – the essential behind-the-scenes work that kept the organization functioning. Through this position, Parks witnessed firsthand the systemic nature of racism and developed the organizational skills that would later prove crucial during the bus boycott.

5. The Recy Taylor Investigation

In 1944, Rosa Parks traveled rural Alabama roads investigating a horrific crime. Recy Taylor, a young Black mother, had been kidnapped and brutally assaulted by six white men who faced no consequences despite confessing. As the NAACP’s lead investigator, Parks documented Taylor’s testimony and helped form the Committee for Equal Justice. The case revealed the double standard of justice – white men could violate Black women with impunity while the slightest perceived offense by Black men often meant death. This lesser-known chapter in Parks’ activism demonstrates her commitment to fighting sexual violence against Black women decades before #MeToo.

6. The Highlander Folk School

Summer 1955 found Rosa Parks at a transformative workshop in the Tennessee mountains. The Highlander Folk School, a rare integrated space in the segregated South, trained activists in nonviolent resistance strategies. Here, Parks exchanged ideas with labor organizers, civil rights leaders, and fellow change-makers. The experience strengthened her conviction that segregation could be challenged through coordinated, nonviolent action. Just months before her historic bus stand, this training provided Parks with both practical organizing tactics and the emotional fortitude to face what lay ahead. Highlander’s influence on Parks’ approach to activism cannot be overstated.

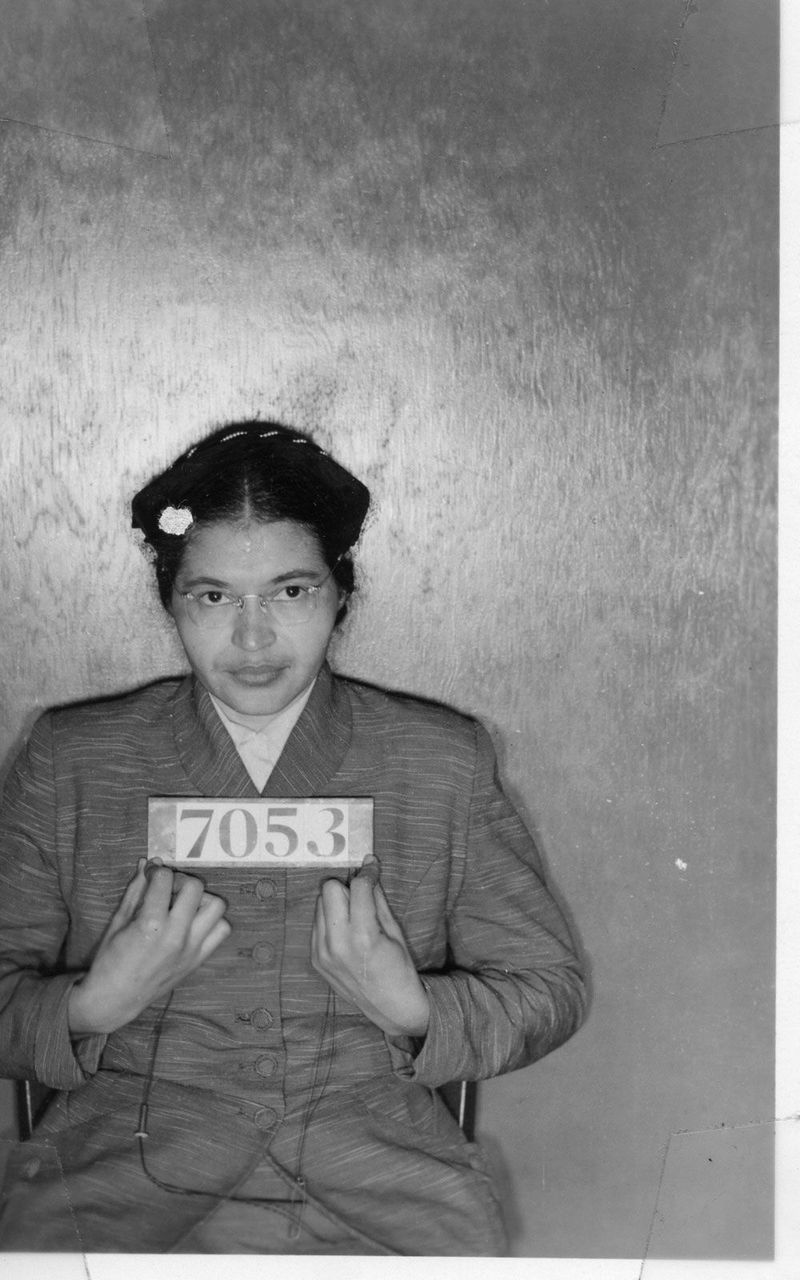

7. The Day That Changed America

December 1, 1955 began as an ordinary Thursday. Parks, exhausted from her work as a department store seamstress, boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus for her journey home. When driver James Blake demanded she surrender her seat to a white passenger, something crystallized within her. “No,” she simply stated. This wasn’t impulsive defiance – it was the culmination of years of activism and personal dignity. Her arrest that evening for violating Montgomery’s segregation ordinance might have been just another indignity suffered by Black citizens, but instead became the spark that ignited a movement. Parks later explained: “The only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

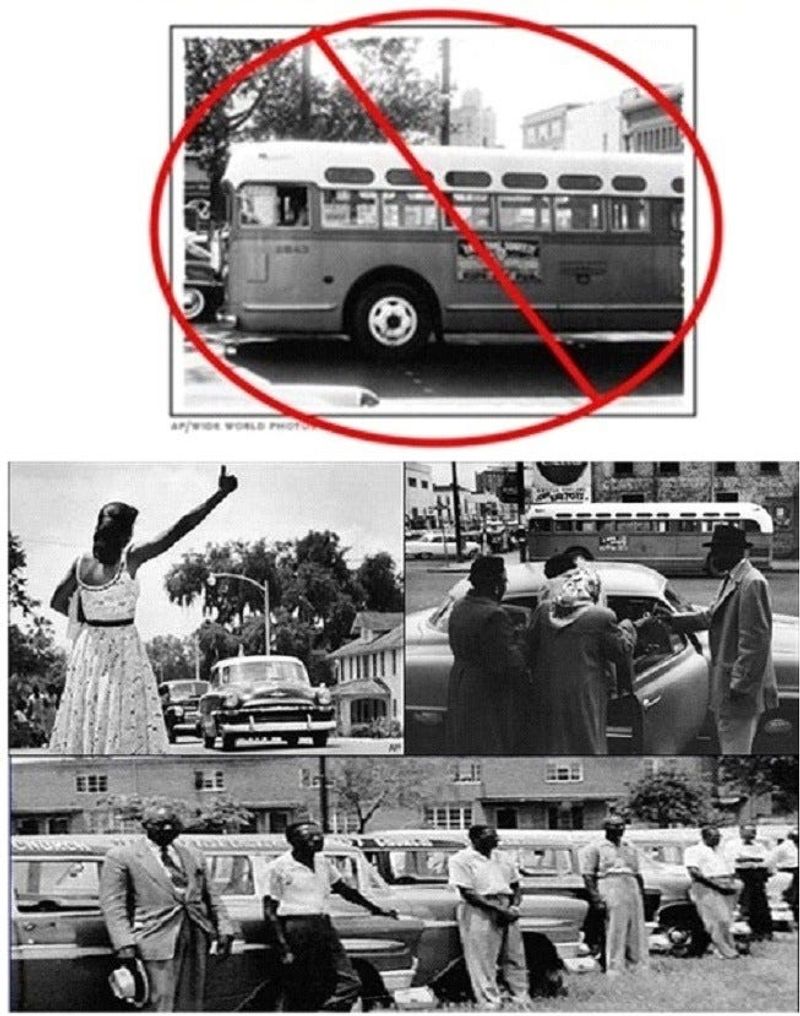

8. Organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Within hours of Parks’ arrest, a remarkable mobilization began. E.D. Nixon recognized the perfect case to challenge segregation, while Jo Ann Robinson and the Women’s Political Council worked through the night mimeographing 35,000 flyers calling for a one-day boycott. Black Montgomery residents demonstrated extraordinary solidarity – empty buses rolled through the city on December 5th. A young minister named Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as the boycott’s voice, but Parks’ quiet dignity remained its heart. What began as a one-day protest evolved into a 381-day economic action that brought Montgomery’s transit system to its knees while demonstrating Black citizens’ remarkable capacity for organized resistance.

9. Victory in the Supreme Court

While the boycott applied economic pressure, attorneys filed Browder v. Gayle challenging bus segregation’s constitutionality. Though Parks wasn’t a plaintiff, her case provided the catalyst. On November 13, 1956, victory arrived when the Supreme Court ruled Montgomery’s bus segregation unconstitutional. After 381 days of walking, carpooling, and enduring harassment, Black citizens returned to integrated buses on December 21, 1956. This triumph demonstrated how collective action combined with legal strategy could dismantle segregation. The boycott’s success established a template for challenging Jim Crow laws nationwide and proved that ordinary citizens could successfully confront entrenched systems of oppression.

10. The Cost of Courage

Fame brought severe consequences. Both Rosa and Raymond lost their jobs – she from the department store, he from his barber position. Hate mail flooded their home, death threats arrived regularly, and economic pressure mounted as white Montgomery closed ranks. Their phone rang constantly with obscene calls and threats against their lives. The psychological toll was immense. Friends recall Parks jumping at sudden noises, constantly checking windows, and struggling with insomnia. This period reveals how civil rights activism demanded not just momentary courage but sustained endurance in the face of retaliation. The Parks family paid a steep personal price for challenging the status quo.

11. New Life in Detroit

Seeking safety and opportunity, Parks and her husband relocated to Detroit in 1957. Her sister Sylvester already lived there, offering family support during this difficult transition. Detroit’s large Black community welcomed Parks, but starting over at 44 wasn’t easy. Finding stable employment proved challenging despite her fame – or perhaps because of it. Many employers feared hiring such a prominent civil rights figure. Though often portrayed as simply fleeing Montgomery, this move represented Parks’ continued commitment to the movement. In Detroit, she found new avenues for activism while connecting the struggles of Northern and Southern Black communities.

12. Working with Congressman Conyers

In 1965, Parks found a political home on Congressman John Conyers’ staff. As his receptionist and office manager, she helped constituents navigate government bureaucracy and ensured their voices reached Washington. This position connected her directly to the legislative process during a pivotal era that saw the passage of the Voting Rights Act and Fair Housing Act. Parks brought firsthand knowledge of segregation’s impact to Capitol Hill through Conyers’ office. For 23 years until her 1988 retirement, Parks served Detroit’s predominantly Black district, transforming her role from symbolic figure to practical problem-solver. This period demonstrated her commitment to translating protest into policy.

13. Founding the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute

Following Raymond’s death in 1977, Parks channeled her grief into creating something meaningful. In 1987, she co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development with her friend Elaine Eason Steele. The Institute focused on youth development through programs like Pathways to Freedom, which took teenagers on bus tours of civil rights landmarks. Parks believed deeply in connecting young people to their history while preparing them for future leadership. Well into her seventies, Parks remained actively involved, often traveling with students and sharing firsthand accounts of the movement. This work ensured her legacy would extend beyond her famous act of resistance.

14. Global Recognition and Honors

The woman once arrested for sitting on a bus eventually received her nation’s highest honors. In 1996, President Clinton awarded Parks the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and in 1999, she received the Congressional Gold Medal – the only woman to receive both distinctions that century. Universities worldwide bestowed honorary degrees recognizing her contribution to human rights. TIME magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. These accolades represented more than personal recognition – they signified America’s evolving relationship with its civil rights history. The nation that once criminalized Parks’ dignity now celebrated her courage as quintessentially American.

15. Final Years and Passing

Parks faced health challenges in her later years, including dementia and progressive illness. Despite these difficulties, she maintained her dignity and occasionally appeared at significant events. On October 24, 2005, at age 92, Parks passed away in her Detroit apartment. The nation mourned collectively – flags flew at half-staff, and her body lay in honor in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, the first woman and second African American accorded this distinction. More than 50,000 people viewed her casket in Washington before her Detroit funeral drew civil rights leaders, politicians, and ordinary citizens whose lives she had transformed. Her quiet departure matched the dignified determination that defined her life.

16. Living Legacy

Parks’ influence extends far beyond her lifetime. Schools, streets, buildings and transit centers across America bear her name. The bus where she took her stand is preserved at the Henry Ford Museum, while her personal papers reside in the Library of Congress. Her birthday, February 4, is celebrated as Rosa Parks Day in several states. Modern social justice movements frequently invoke her example of peaceful resistance and moral clarity. Perhaps most importantly, Parks transformed from historical figure to cultural touchstone – a universal symbol of courage in the face of injustice. Her simple act continues inspiring those who, in her words, are “tired of giving in” to oppression.