Helen Keller’s extraordinary journey from a deaf-blind child to a world-renowned advocate created ripples of change that continue today. Despite facing seemingly insurmountable obstacles, she transformed public perception about disability and fought tirelessly for social justice. Her remarkable life demonstrates how one person’s determination can reshape society and inspire generations.

1. Breaking Educational Barriers

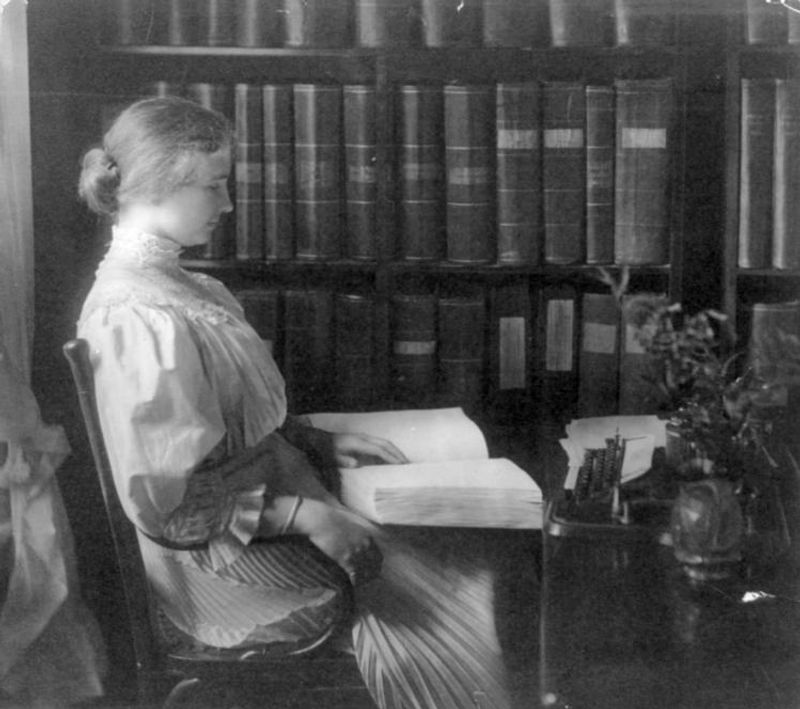

In 1904, Helen Keller shattered glass ceilings by becoming the first deafblind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree. Graduating cum laude from Radcliffe College, she demolished prevailing beliefs about disability limitations.

Her academic journey required incredible persistence—textbooks weren’t available in braille, so Anne Sullivan had to spell every word into her hand. Fellow students and professors initially doubted her abilities.

This groundbreaking achievement forced society to reconsider what was possible for people with disabilities. Her graduation made headlines nationwide, beginning a lifelong mission of proving that disability doesn’t equal inability.

2. Creating a Global Health Organization

Helen co-founded Helen Keller International in 1915, establishing what would become one of the world’s premier nonprofit organizations fighting preventable blindness and malnutrition. Originally focused on veterans blinded during World War I, the organization evolved to address broader public health challenges.

Today, HKI operates in over 20 countries across Africa, Asia, and the United States. Their programs deliver essential vitamins, improve nutrition, and provide vision services to millions of vulnerable people annually.

Keller’s vision created an enduring legacy that continues saving sight and lives more than a century later—a testament to her understanding that disability advocacy requires systemic solutions.

3. Championing Civil Liberties

Few know that Helen Keller helped establish the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1920. As a founding member, she recognized that disability rights existed within a broader framework of human dignity and freedom.

Her involvement wasn’t passive—she actively participated in early meetings and lent her growing celebrity to the fledgling organization. The ACLU would go on to defend Americans’ constitutional rights for generations.

While many remember Keller solely for overcoming personal challenges, this work reveals her sophisticated understanding of systemic oppression. She recognized that marginalized groups—whether defined by disability, race, gender, or political belief—required legal protection against discrimination.

4. Revolutionizing Disability Advocacy

Keller transformed disability advocacy from charity to civil rights. Through her work with the American Foundation for the Blind, she shifted public perception from pity toward recognizing the capabilities and rights of disabled individuals.

She testified before Congress numerous times, demanding education funding and employment protections. Her celebrity status opened doors typically closed to advocates, allowing her unprecedented access to presidents, business leaders, and influencers.

Unlike earlier approaches that emphasized institutionalization, Keller insisted on integration and independence. She made the radical argument that people with disabilities deserved not just basic care but full participation in society—a revolutionary concept that laid groundwork for later legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act.

5. Expanding International Influence

Helen’s global impact extended far beyond American borders. Throughout her lifetime, she visited 39 countries across five continents, meeting with world leaders and ordinary citizens alike. Japan alone established over 70 schools for the blind based on her influence!

Her 1937 trip to Japan became legendary when she introduced the Akita dog breed to America. In 1946, General MacArthur specifically requested her return to boost Japanese morale after WWII.

Keller’s international advocacy transcended Cold War politics. She visited both democratic and communist nations, maintaining that disability rights weren’t political but universal. Her global perspective helped establish disability advocacy as an international human rights movement rather than just an American concern.

6. Transforming Through Words

Keller’s pen proved mightier than her disabilities. Despite never seeing or hearing a single word, she authored 12 books and countless articles that transformed how society viewed disability. Her autobiography, “The Story of My Life,” has never gone out of print since 1903!

Her writing style defied expectations—vivid, emotional, and filled with sensory descriptions that amazed critics. Mark Twain famously called her one of the two most interesting characters of the 19th century alongside Napoleon.

Beyond personal narrative, her later works addressed philosophical and social issues. Through her prolific writing, Keller demonstrated that intellectual contribution shouldn’t be limited by physical ability, permanently altering public perception about the cognitive capabilities of disabled individuals.

7. Fighting for Women’s Voices

Keller’s fierce advocacy for women’s suffrage emerged naturally from her own struggle for voice. As someone who had literally fought for the right to communicate, she understood the fundamental injustice of silencing women politically.

She joined the women’s suffrage movement during its most militant phase, writing passionate articles and appearing at rallies. Her public support provided crucial momentum during the final push toward the 19th Amendment.

What made her advocacy particularly powerful was her intersectional approach. Decades before such terminology existed, Keller recognized connections between disability rights and women’s rights, arguing that both involved fighting artificial limitations imposed by society rather than actual capability.

8. Advocating for Economic Justice

Keller’s radical economic views often get sanitized from her legacy. She didn’t just join the Socialist Party—she became one of its most prominent members, writing for socialist publications and supporting strikes. Factory owners who praised her courage suddenly grew quiet when she criticized their labor practices!

Her socialism wasn’t separate from her disability advocacy but directly informed by it. Having experienced marginalization, she recognized capitalism’s tendency to value people based on productivity rather than inherent worth.

The FBI maintained an extensive file on her activities, considering her dangerously influential. Despite pressure to moderate her views, Keller maintained that economic justice was inseparable from disability rights—a perspective that challenged both conservatives and many mainstream disability organizations.

9. Standing Against Racial Discrimination

Keller boldly confronted racism decades before the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum. In 1916, she publicly condemned lynching—a dangerous position for anyone, but particularly for a woman dependent on public goodwill for her livelihood.

Her support for the NAACP went beyond token membership. She corresponded regularly with W.E.B. Du Bois and used her platform to amplify Black voices when few white Americans would.

Southern newspapers that had celebrated her achievements turned against her after these stances. Speaking engagements were canceled, and funding threatened. Nevertheless, Keller persisted in drawing connections between different forms of discrimination, recognizing that systems of oppression share common roots regardless of which group they target.

10. Revolutionizing Special Education

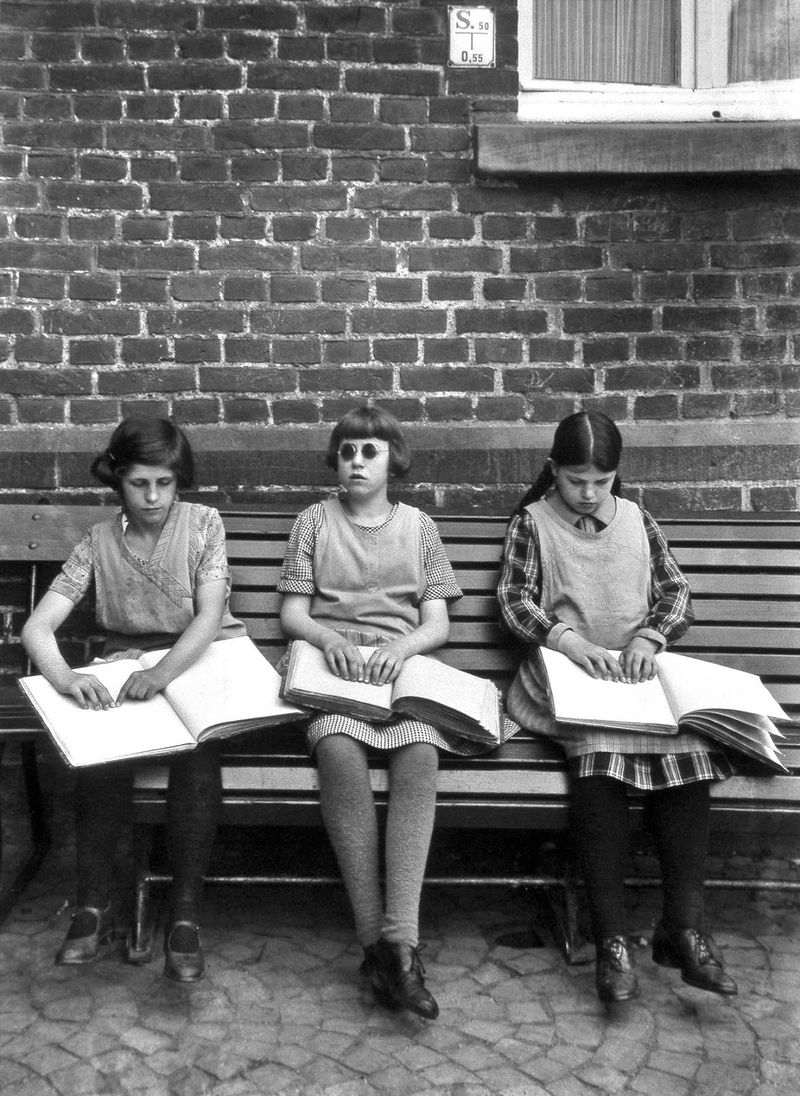

Before Keller, education for disabled children barely existed. Most were kept at home or institutionalized with minimal instruction. Her success story sparked a revolution in expectations and methodologies for teaching disabled students.

She advocated tirelessly for specialized teaching methods while insisting disabled students deserved access to the same curriculum as their peers. This dual approach—acknowledging difference while demanding equality—transformed special education philosophy.

Keller didn’t just inspire abstract change; she helped establish concrete programs. Schools for blind and deaf students worldwide modeled their approaches on her education. The “Keller method” became shorthand for high expectations combined with adaptive techniques—a philosophy that continues influencing inclusive education today.

11. Reshaping Disability Legislation

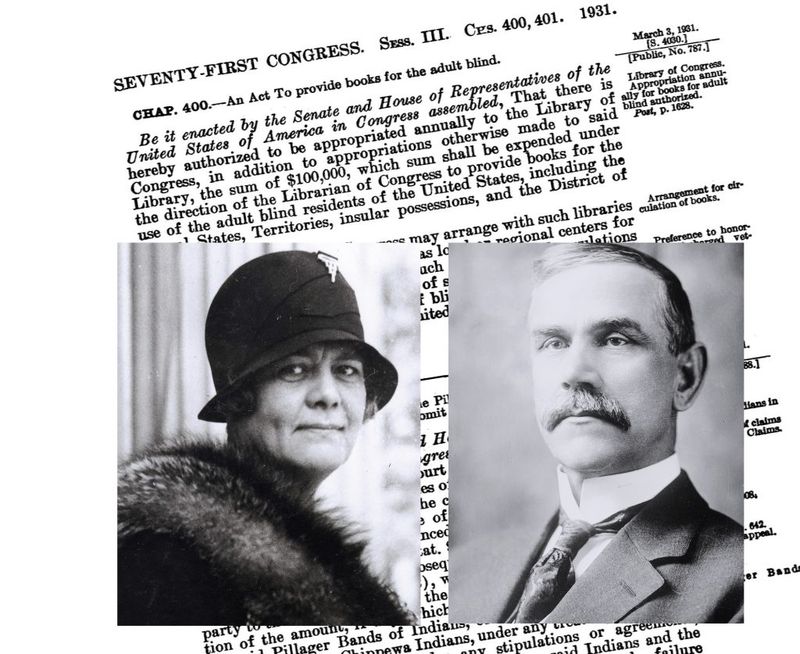

Keller’s fingerprints remain on disability legislation enacted decades after her death. As a lobbyist for the American Foundation for the Blind, she personally convinced Congress to approve reading materials and services for blind Americans.

Her 1929 testimony directly led to the Pratt-Smoot Act, which funded the Library of Congress’s talking book program that continues today. She later secured Social Security benefits for blind Americans, creating the first federal disability assistance program.

These early victories established crucial precedents: government responsibility for disability accommodation and the right of disabled people to participate in policy decisions affecting them. Every subsequent piece of disability legislation—from the Rehabilitation Act to the Americans with Disabilities Act—builds upon foundations Keller established.

12. Receiving Presidential Recognition

The Presidential Medal of Freedom—America’s highest civilian honor—recognized Keller’s lifetime of achievement in 1964. President Lyndon B. Johnson personally presented the medal, acknowledging her contributions transcended disability advocacy to fundamentally reshape American society.

This wasn’t her first presidential recognition. She had met every U.S. president from Grover Cleveland to John F. Kennedy, using these relationships to advance disability policy. The Truman Library contains extensive correspondence showing her direct influence on his administration.

The medal ceremony, broadcast nationwide just months before her death, provided a final platform for her message. Even in her 80s, Keller used the opportunity not for self-congratulation but to emphasize work still needed—demonstrating the relentless advocacy that defined her life.

13. Inspiring Artistic Portrayals

“The Miracle Worker” transformed Keller from historical figure to cultural icon. The 1959 play and subsequent 1962 film dramatized her childhood breakthrough in learning language, winning multiple Tony and Academy Awards and introducing her story to millions worldwide.

Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke’s powerful performances in the iconic water pump scene—where young Helen finally connects the manual sign for “water” with the actual substance—became one of cinema’s most memorable moments. The film’s success sparked renewed interest in disability education.

Beyond entertainment value, these artistic interpretations fundamentally altered public perception about disability potential. For many Americans, Keller’s story provided their first exposure to the idea that deafblind individuals could communicate, learn, and contribute meaningfully to society.

14. Establishing Specialized Services

The Helen Keller National Center (HKNC), established by Congress in 1967, created America’s only comprehensive national program serving people with combined vision and hearing loss. Located in Sands Point, New York, this pioneering institution directly translated Keller’s advocacy into practical support.

HKNC provides vocational rehabilitation, independent living training, and community integration services. Their innovative approach combines multiple disciplines to address the unique challenges of deafblindness.

Beyond direct services, the center trains professionals nationwide, conducts research, and develops adaptive technologies. This multifaceted approach reflects Keller’s understanding that disability support requires both individual services and systemic change—creating a living legacy that continues empowering deafblind Americans to achieve their full potential.

15. Becoming an Enduring Symbol

Helen Keller’s legacy lives on through international commemoration. Helen Keller Day, observed annually on her birthday (June 27), celebrates her extraordinary life and contributions through events worldwide. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter formalized this recognition.

Her birthplace in Tuscumbia, Alabama—including the famous water pump—is now a museum attracting thousands of visitors annually. The Helen Keller Archives at the American Foundation for the Blind preserve her correspondence, photographs, and personal items.

Perhaps most significantly, her image appears on the Alabama state quarter, making her the first person with disabilities featured on U.S. currency. These commemorations ensure her story continues inspiring future generations, maintaining her status as the world’s most recognized symbol of disability achievement.