Movies often leave us with questions, but dedicated fans fill these gaps with fascinating theories. Cult films especially inspire passionate debate about hidden meanings, secret connections, and alternate interpretations.

These theories transform how we experience these beloved classics, adding new layers of meaning with each rewatch. Ready to see your favorite cult films in a completely different light?

1. Neo Is Not The One

Reality-bending theories surround The Matrix, but this one flips the entire premise on its head. Agent Smith, not Neo, fulfills the prophecy as “The One” by bringing balance to the Matrix through his viral takeover and eventual self-sacrifice.

The evidence is compelling. Smith evolves beyond his programming, develops free will, and ultimately destroys the system from within. Neo serves merely as a catalyst for Smith’s transformation.

When Smith absorbs Neo in the final battle, their combined destruction resets the Matrix, creating the balance the Oracle predicted—something Neo alone never achieved.

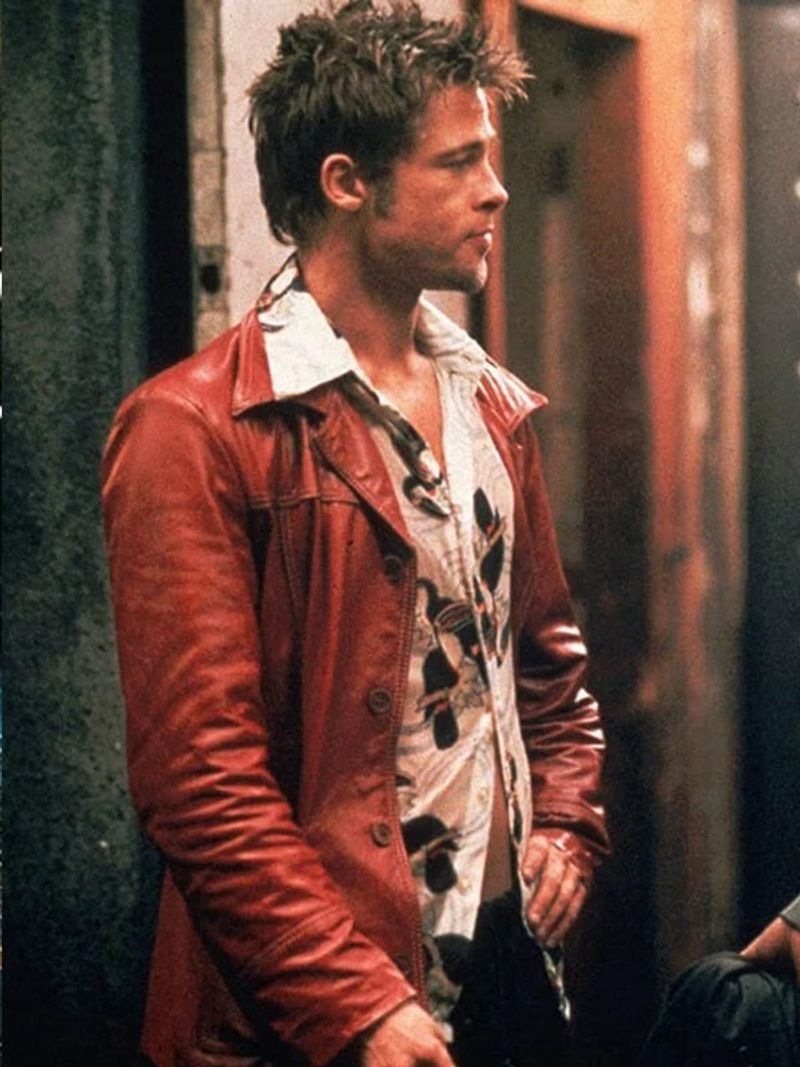

2. Tyler Durden: Divine Projection

Beyond mental illness lies a cosmic interpretation of Fight Club. Tyler Durden represents a god-like entity guiding the narrator toward enlightenment through chaos and destruction.

His supernatural knowledge, ability to appear anywhere, and prophetic vision suggest something beyond human consciousness. Tyler’s philosophy mirrors ancient destructive deities who bring renewal through chaos.

The narrator’s eventual “killing” of Tyler represents not victory over mental illness, but the completion of a spiritual transformation. This theory explains Tyler’s impossible knowledge and the cult-like devotion he inspires in others.

3. Donnie Darko’s Universe-Saving Time Loop

The rabbit-costumed Frank isn’t just a hallucination—he’s a guide helping Donnie repair a fracture in reality. According to passionate theorists, Donnie exists in a predetermined time loop created to prevent universal collapse.

The “manipulated dead” (like Frank) guide Donnie through necessary actions to restore proper timeline flow. His death isn’t tragic but sacrificial and essential.

Each strange event—the jet engine, the flooding school, the “living receiver” concept—represents pieces of a cosmic puzzle Donnie must solve. The smile in his final scene suggests he understands his purpose at last.

4. Marsellus Wallace’s Soul in a Briefcase

Pulp Fiction’s golden glow has sparked endless debate. The mysterious briefcase—opened with the combination “666”—supposedly contains something supernatural: Marsellus Wallace’s soul.

Observant viewers point to the Band-Aid on Wallace’s neck, theorizing it covers where the devil extracted his soul. This explains why retrieving the briefcase is worth killing for and why it emits an otherworldly glow.

When Vincent opens it, we see wonder on his face but never the contents. The theory connects Biblical references throughout the film with Tarantino’s love of leaving crucial elements to viewers’ imagination.

5. Donny: The Big Lebowski’s Ghost

Watch carefully—nobody except Walter directly acknowledges Donny’s existence throughout The Coen Brothers’ classic. This observation birthed the theory that Donny is actually a ghost or figment of Walter’s imagination.

Donny represents Walter’s lingering connection to Vietnam, perhaps a fallen comrade whose memory Walter can’t release. The Dude tolerates Walter’s conversations with “Donny” out of friendship.

The bowling alley serves as limbo where Walter processes his trauma. When Donny “dies” of a heart attack, it symbolizes Walter finally making peace with his past—explaining the elaborate funeral for someone supposedly insignificant.

6. The Shining’s Hidden Holocaust Metaphor

Stanley Kubrick’s meticulous attention to detail wasn’t accidental. Eagle-eyed viewers have documented numerous Holocaust references throughout The Shining, suggesting the film doubles as commentary on genocide.

Room 237—a number linked to the Holocaust through multiplication (2x3x7=42, referring to 1942)—becomes the film’s symbolic center. The Overlook Hotel itself represents historical amnesia, built atop Native American burial grounds while displaying Germanic décor.

Jack’s typewriter mysteriously changes color from scene to scene—from American to German-made—while Danny wears an Apollo 11 sweater, nodding to Kubrick’s rumored involvement in faking the moon landing.

7. Cobb Never Escapes the Dream

Inception’s spinning top ending leaves viewers hanging, but a subtle detail throughout the film reveals the truth. Cobb’s actual totem isn’t the top—it’s his wedding ring.

Throughout the movie, Cobb wears his ring only in dream sequences. In the final airport scene, his ring is absent, suggesting reality. However, other inconsistencies remain.

His children appear unchanged despite years passing, and they wear the exact clothes from his memories. The entire film might represent Cobb’s failed attempt to process guilt over Mal’s death, with the spinning top deliberately distracting viewers from the true indicators of reality.

8. Ferris Bueller: Cameron’s Alter Ego

Much like Tyler Durden, Ferris Bueller might not exist at all. Some theorists believe he’s merely Cameron’s imaginary projection—the confident, carefree person Cameron wishes he could be.

Cameron, trapped in depression and fear of his father, creates Ferris to mentally escape his constraints. The elaborate day off represents Cameron’s internal journey toward self-acceptance and standing up to authority.

Notice how Ferris accomplishes impossible feats without consequences and how the adults who interact with “Ferris” behave cartoonishly. The Ferrari’s destruction symbolizes Cameron finally confronting his father through his imaginary confident self.

9. Sandy’s Heavenly Ascension in Grease

“Summer lovin’ happened so fast”—perhaps because it never really happened at all. According to this dark theory, Sandy actually drowned during the beach scene mentioned in the opening song.

The entire musical represents her dying fantasy or purgatory experience. Danny’s initial description of saving Sandy contradicts her version, suggesting one account isn’t real.

The film’s bizarre finale—where the couple literally flies away in a car—suddenly makes sense as Sandy’s ascension to heaven. Other clues include the surreal dream sequences, impossible makeovers, and the song “Look at Me, I’m Sandra Dee” foreshadowing Sandy’s death.

10. The Thing’s Secret Infection Test

John Carpenter’s masterpiece ends with MacReady and Childs sharing whiskey in the Antarctic cold, neither trusting the other. A subtle detail reveals the truth: MacReady’s “whiskey” is actually gasoline.

Earlier, we see MacReady creating Molotov cocktails. When he offers Childs a drink, he’s testing him—a Thing would not react to drinking gasoline, while a human would.

Childs drinks without reaction, confirming he’s infected. Alternatively, MacReady’s breath doesn’t steam like Childs’, suggesting MacReady himself is The Thing. Either way, humanity loses—exactly the bleak ending Carpenter intended.

11. Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory of Death

Beneath the colorful candy coating lies a sinister theory: Wonka is methodically eliminating children he deems unworthy. His factory isn’t just a wonderland—it’s an elaborate judgment chamber.

Each room represents a deadly sin, with traps designed to tempt specific character flaws. The Oompa-Loompas aren’t surprised by accidents because there are no accidents.

Wonka’s nonchalance toward potentially fatal situations and his prepared songs for each “accident” suggest premeditation. The boat tunnel scene reveals his true nature—a judge seeking an heir pure enough to continue his legacy, not a kindly candy maker.

12. Deckard: Blade Runner or Replicant?

Harrison Ford’s character hunts artificial humans with ruthless efficiency, but what if he’s one himself? Director Ridley Scott eventually confirmed this theory, but the original film left deliberate clues.

Deckard’s apartment contains family photos despite his isolation, mirroring how replicants are given false memories. His eyes occasionally reflect light like other replicants, particularly during key scenes.

The unicorn dream sequence connects to Gaff’s origami unicorn left at Deckard’s apartment—how could Gaff know about this dream unless it was implanted? As a replicant himself, Deckard’s hunt becomes tragically ironic, explaining his eventual sympathy for those he hunts.

13. The Babadook: Grief Personified

While the director has acknowledged this interpretation, fans elevated The Babadook’s metaphorical monster to iconic status. The top-hatted creature represents unprocessed grief and depression following traumatic loss.

Amelia’s inability to discuss her husband’s death creates the manifestation, growing stronger as she continues to deny her feelings. The film’s brilliant resolution isn’t about defeating the monster but acknowledging it.

The final scene shows Amelia feeding the Babadook in the basement—a perfect metaphor for healthy grief management. You don’t eliminate grief; you learn to give it appropriate space without letting it control your life.

14. Beetlejuice’s Secret: Lydia Was Already Dead

“I myself am strange and unusual”—Lydia’s famous line takes on new meaning with this theory. Her ability to see the Maitlands when no one else can suggests she’s not just goth—she’s actually a ghost herself.

Her connection to death, morbid artwork, and contemplation of suicide point to someone already between worlds. Her father and stepmother’s emotional distance might represent their subconscious grief over her death.

Beetlejuice’s interest in marrying her makes more sense if she’s already dead. The “Handbook for the Recently Deceased” appears precisely when she needs it—because it’s meant for her, not the Maitlands.

15. The Truman Show’s Willing Participant

What if Truman knew all along? This radical theory suggests he was aware of his artificial reality but played along out of fear or comfort until finding the courage to leave.

Evidence includes his periodic testing of patterns and boundaries, plus his remarkably quick acceptance of the truth when confronted. His rehearsed-seeming cheerfulness appears more like someone performing what’s expected than genuine naivety.

The boat scene represents not discovery but decision—choosing freedom over comfortable imprisonment. This interpretation transforms the film from a story about deception to one about the courage required to leave situations we know are false but find comfortingly familiar.

16. Edward Scissorhands: Modern Prometheus

Tim Burton’s gothic fairy tale parallels Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in fascinating ways. Both feature isolated creators playing god, both “monsters” are gentle souls seeking connection, and both stories end with society rejecting what it doesn’t understand.

Edward, like Frankenstein’s creature, represents the ultimate outsider—physically incapable of human touch despite deeply human emotions. His creator dies before completing him, leaving him eternally unfinished.

The snowy ending mirrors Frankenstein’s Arctic conclusion, with Edward retreating to isolation after his brief connection with humanity. Burton deliberately included these parallels as commentary on how society continues to create then reject its “monsters.”

17. Sarah’s Transformation into the Goblin Queen

The glitter doesn’t simply fade away when Labyrinth ends. A persistent theory suggests Sarah never truly returns to reality—she chooses to remain in the fantasy world as Jareth’s replacement.

Her bedroom mirror shows her continued connection to the goblin realm. The toys disappearing from her room symbolize her abandoning childish things not for adulthood, but for magical sovereignty.

Jareth’s offer—”fear me, love me, do as I say”—parallels the responsibility of ruling. When Sarah declares “you have no power over me,” she’s not rejecting the Labyrinth but claiming its power for herself, becoming what she was meant to be: the new Goblin Queen.