Books have a magical way of becoming status symbols in our conversations. We’ve all nodded along when someone mentions a literary classic, afraid to admit we’ve never actually turned its pages. Sometimes it’s to seem smarter at dinner parties, sometimes it’s to avoid the judgment of well-read friends. Here’s our rundown of the 17 books people most commonly claim to have read, but probably just know from movie adaptations, cultural references, or those life-saving SparkNotes.

1. Ulysses by James Joyce

Considered the Mount Everest of literature, this modernist maze follows Leopold Bloom through Dublin on June 16, 1904. Ask anyone about it, and they’ll mumble something about stream-of-consciousness and literary innovation.

Most readers abandon ship after the first few chapters, overwhelmed by Joyce’s dense references and experimental style. The book has developed a reputation as simultaneously essential and impenetrable.

Fun fact: Dedicated fans celebrate Bloomsday every June 16th, retracing Bloom’s steps through Dublin—probably having read more pages of the novel than most who claim to have conquered it.

2. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

The ultimate doorstop novel spans seven years of Russian society during the Napoleonic era. At over 1,200 pages featuring 580 characters (many with multiple Russian names), it’s no wonder most people only pretend to have read it.

Tolstoy’s epic masterfully weaves historical events with fictional narratives about five aristocratic families. The sheer physical weight of the book has become symbolic of intellectual ambition.

Many booklovers proudly display War and Peace on their shelves, occasionally dusting it while secretly knowing they’ll probably never make it past the famous opening line about happy and unhappy families—which is actually from Anna Karenina.

3. Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace

The literary equivalent of running an ultramarathon, Wallace’s 1996 opus sprawls across 1,079 pages plus nearly 100 pages of endnotes. Set in a near-future North America, it tackles addiction, entertainment, and tennis with encyclopedic ambition.

The book has become a cultural touchstone that many claim to have read but few have finished. Its reputation precedes it—a complex puzzle box of narratives that requires dedication, multiple bookmarks, and possibly a support group.

Carrying this brick-like tome in public signals intellectual seriousness. Secretly, most readers tap out somewhere around page 200, before the plot threads begin connecting in meaningful ways.

4. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

“Call me Ishmael” might be the most famous opening line from a book that relatively few people have actually finished. Melville’s 1851 epic about Captain Ahab’s obsessive pursuit of a white whale is interspersed with lengthy chapters on whaling techniques, cetology, and nautical minutiae.

The novel flopped when published but later gained recognition as the Great American Novel. Modern readers often find themselves adrift in detailed passages about whale anatomy or rope-making.

Most people know the basic plot and iconic characters but would struggle to discuss anything beyond Chapter 1. The white whale has become a metaphor for unattainable goals—including finishing the book itself.

5. The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri

This 14th-century Italian epic poem follows Dante’s journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Written in an obsolete Tuscan dialect and structured around medieval Catholic theology, it’s hardly light reading for modern audiences.

Most people recognize the famous “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here” inscription at Hell’s gate or Gustave Doré’s haunting illustrations. The nine circles of Hell concept has permeated popular culture.

The Divine Comedy represents the quintessential book everyone claims familiarity with based on cultural osmosis alone. In reality, reading all three canticles (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso) requires serious scholarly commitment that few undertake outside of university literature courses.

6. Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

Rand’s philosophical novel depicts a dystopian United States where creative industrialists withdraw from society in protest against collectivism. At over 1,000 pages, it’s notorious for John Galt’s 60-page speech expounding Rand’s Objectivist philosophy.

Many claim to have read it as a formative influence or ideological touchstone. Politicians frequently cite it despite evidence suggesting they’ve never finished it. The book has developed a cult following while simultaneously becoming a symbol of intellectual posturing.

Most “readers” know the basic premise and perhaps the catchphrase “Who is John Galt?” but would struggle to discuss specific plot points beyond the first few chapters. The novel’s length serves as both its claim to importance and the reason most people abandon it.

7. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Raskolnikov’s psychological journey after murdering a pawnbroker has captivated—and intimidated—readers since 1866. This Russian masterpiece explores morality, redemption, and the consequences of believing oneself above conventional morality.

Many claim familiarity with Dostoevsky’s psychological thriller but falter when discussions move beyond basic plot points. The novel’s reputation for philosophical depth makes it perfect for intellectual name-dropping.

Readers often underestimate the novel’s accessibility, scared off by its Russian names and existential themes. Those who pretend to have read it typically know only that it involves an axe murder and subsequent guilt, missing Dostoevsky’s profound exploration of human psychology that makes the challenging read worthwhile.

8. Finnegans Wake by James Joyce

Joyce’s final work represents the Everest beyond Everest in literary difficulty. Written in a dream-language combining multilingual puns, portmanteaus, and obscure references, it begins mid-sentence and ends with the beginning of that same sentence.

Anyone claiming to have read and understood this experimental novel is almost certainly exaggerating. Even dedicated Joyce scholars approach it with humility. The first line—”riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay”—might be the only part most “readers” can quote.

The book has developed a reputation as the ultimate literary challenge, more often referenced than read. Those who’ve genuinely tackled it typically join reading groups or use annotated guides just to make minimal progress through its linguistic labyrinth.

9. The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s final novel explores faith, doubt, and morality through the story of three brothers and their disturbing father. At nearly 800 pages of dense philosophical dialogue, most readers who begin this journey never see it through to completion.

The famous “Grand Inquisitor” chapter often appears in philosophy courses, allowing many to claim familiarity with the whole work. The novel tackles fundamental questions about God’s existence and human suffering with unparalleled depth.

When mentioned at literary gatherings, heads nod in recognition while most secretly think of the SparkNotes summary they skimmed in college. Those who claim it as a favorite often remember only isolated philosophical passages rather than the complex family drama that frames them.

10. Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon

Set during the final months of World War II, Pynchon’s postmodern masterpiece follows a complex cast of characters searching for a mysterious rocket. Its nonlinear narrative, obscure references, and paranoid themes have confounded readers since 1973.

The novel’s reputation for difficulty makes it perfect for intellectual posturing. Many own it; few finish it; fewer still comprehend it. Its infamous banana breakfast scene and octopus encounter might be referenced at parties by those pretending familiarity.

Even the Pulitzer committee couldn’t agree on its merit, denying it the prize despite jury recommendation. True readers of Gravity’s Rainbow often develop a cult-like devotion, forming study groups to decipher its mysteries—while the majority of claimed readers have merely admired its rainbow-colored cover on their shelves.

11. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Published in two volumes in 1605 and 1615, this Spanish masterpiece follows the delusional nobleman who believes himself a knight-errant. While nearly everyone recognizes the iconic windmill-tilting scene, few have navigated all 1,000+ pages of Cervantes’ sprawling narrative.

Considered the first modern novel, Don Quixote pioneered techniques still used in fiction today. Its influence is undeniable, but its length and antiquated style present barriers to modern readers.

Most “readers” know the basic premise and perhaps a few famous episodes, but would struggle to discuss the novel’s second half. The term “quixotic” has entered everyday language, allowing many to reference the work without ever having opened it.

12. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

Faulkner’s modernist masterpiece chronicles the decline of the Compson family through four distinct narrative perspectives. The first section, narrated by the intellectually disabled Benjy, notoriously challenges readers with its stream-of-consciousness style and disjointed chronology.

Literary discussions often feature knowing references to “Benjy’s section” or “Quentin’s section” from those who’ve never ventured beyond the first few bewildering pages. The novel’s experimental structure makes it simultaneously prestigious to claim and easy to abandon.

Those who genuinely finish it often need reading guides or multiple attempts. Meanwhile, countless English majors have written papers based primarily on secondary sources, perpetuating the cycle of pretending to have read what many consider the greatest American novel.

13. Les Misérables by Victor Hugo

Hugo’s monumental work follows ex-convict Jean Valjean’s moral redemption in post-revolutionary France. At approximately 1,500 pages (depending on translation), featuring lengthy digressions on Parisian sewers, Waterloo, and monastic life, the unabridged novel demands serious commitment.

Thanks to the hit musical and numerous film adaptations, most people know the basic plot and characters. Many claim to have read it while having experienced only adaptations, perhaps supplemented by a quick Wikipedia overview.

Those who attempt the complete novel often find themselves skimming Hugo’s historical essays. The book’s physical heft alone makes it impressive on a shelf, perfect for suggesting literary sophistication while never requiring actual completion.

14. Middlemarch by George Eliot

Subtitled “A Study of Provincial Life,” Eliot’s panoramic novel explores the intertwined lives of residents in a fictional English town. Published in 1871-72, its 800+ pages of intricate social observation and psychological insight represent the pinnacle of Victorian literature.

Literary critics consistently rank it among the greatest novels ever written. Casual readers, however, often find its deliberate pace and large cast of characters daunting.

Many intellectuals name-drop Middlemarch as a favorite while having absorbed its reputation rather than its text. Those claiming familiarity might reference the idealistic Dorothea Brooke or the failed scientist Lydgate without having followed their complete character arcs through Eliot’s masterful but lengthy narrative.

15. The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer

Written in Middle English during the late 14th century, this collection of 24 stories told by pilgrims traveling to Canterbury Cathedral presents a vivid cross-section of medieval society. The language barrier alone defeats most modern readers before they begin.

Many claim familiarity based on having studied one or two tales in high school or college. “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” or “The Knight’s Tale” might ring bells, but few have tackled the complete work in its original language.

Those who pretend knowledge typically rely on modernized translations or adaptations. True readers require specialized glossaries and annotations to navigate Chaucer’s world—a commitment few make outside academic requirements.

16. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Márquez’s masterpiece traces seven generations of the Buendía family in the fictional town of Macondo. The magical realism classic features multiple characters named Aureliano and José Arcadio, creating a deliberate sense of cyclical confusion that challenges even dedicated readers.

Many claim to have read it based on its status as a revolutionary Latin American novel. The book’s famous opening line about Colonel Aureliano Buendía facing the firing squad provides an easy reference point for pretenders.

Those who abandon the novel often cite the repetitive names as the breaking point. Meanwhile, the truly committed sometimes create family trees to track the complex generational saga that blends history, myth, and magic into a revolutionary narrative that fewer have finished than claim.

17. The Iliad & The Odyssey by Homer

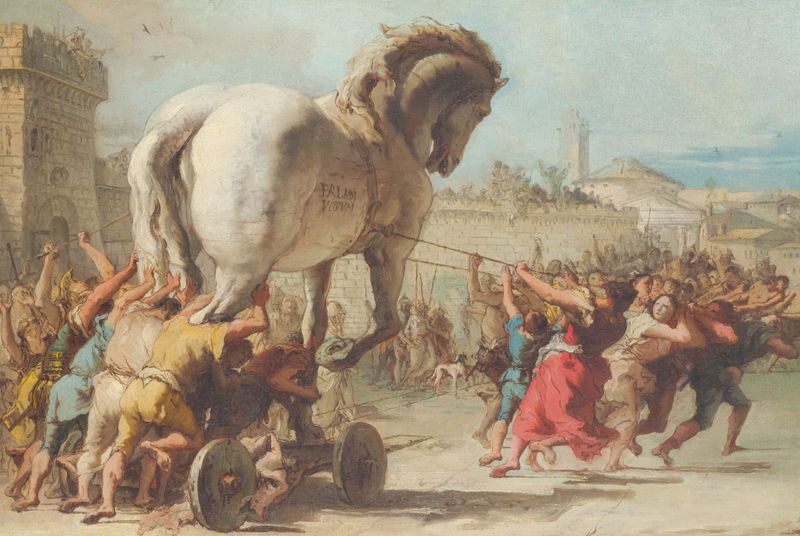

Homer’s ancient Greek epics form the cornerstone of Western literature, but their archaic language and cultural context make them challenging for modern readers. Most people recognize references to the Trojan Horse, Achilles’ heel, or Odysseus’ journey home.

Claiming familiarity with these works signals classical education and cultural literacy. In reality, many “readers” know these stories primarily through movies, adaptations, or cultural references rather than having worked through translations of the original epic poems.

Those who pretend knowledge might mention the opening “Sing, O goddess” invocation or reference “wine-dark seas” without having experienced the full mythological richness of either work. The poems’ length and ancient context create perfect conditions for literary bluffing.