Books have a magical way of surviving through time, speaking to readers across centuries. Some novels, though written long ago, continue to captivate us with their timeless stories and powerful themes. These classics have shaped how we think about literature and often reveal truths about human nature that remain relevant today.

1. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605)

Published over 400 years ago, this Spanish masterpiece follows an aging gentleman who loses his mind reading too many chivalric romances. He creates an alter ego as a knight-errant and embarks on ridiculous adventures with his practical sidekick, Sancho Panza. The novel brilliantly balances comedy with profound insights about human idealism. Cervantes created not just a funny story but a revolutionary narrative that questioned reality itself. Don Quixote introduced techniques still used in modern fiction and remains astonishingly relevant. Its influence reaches from Dickens to Dostoyevsky, making it arguably the first—and perhaps greatest—modern novel ever written.

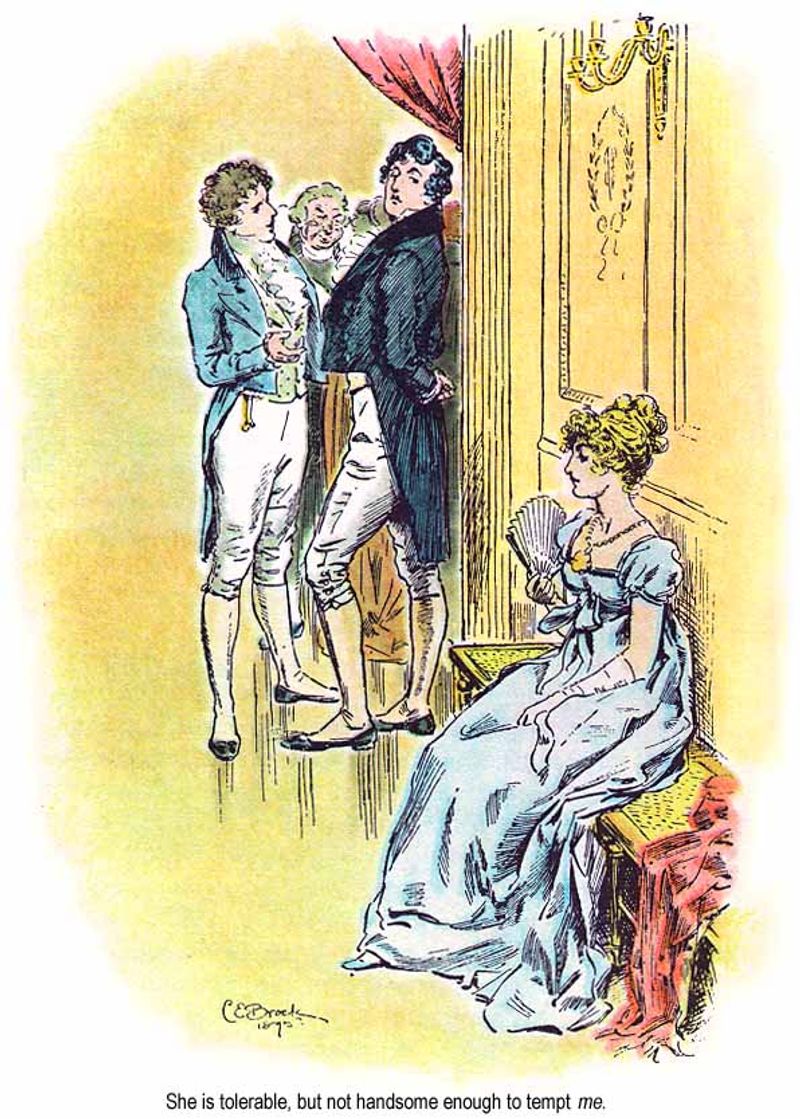

2. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813)

Sparkling with wit and social observation, Austen’s most beloved work centers on the spirited Elizabeth Bennet navigating marriage prospects in early 19th-century England. Her contentious relationship with the proud Mr. Darcy evolves through misunderstandings and revelations about character. Beneath its romantic storyline lies a sharp critique of social conventions and economic realities facing women. Austen crafted characters of remarkable psychological depth despite her limited worldly experience. The novel’s opening line—”It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”—perfectly captures its ironic tone while setting up the marriage-market dynamics that drive the plot.

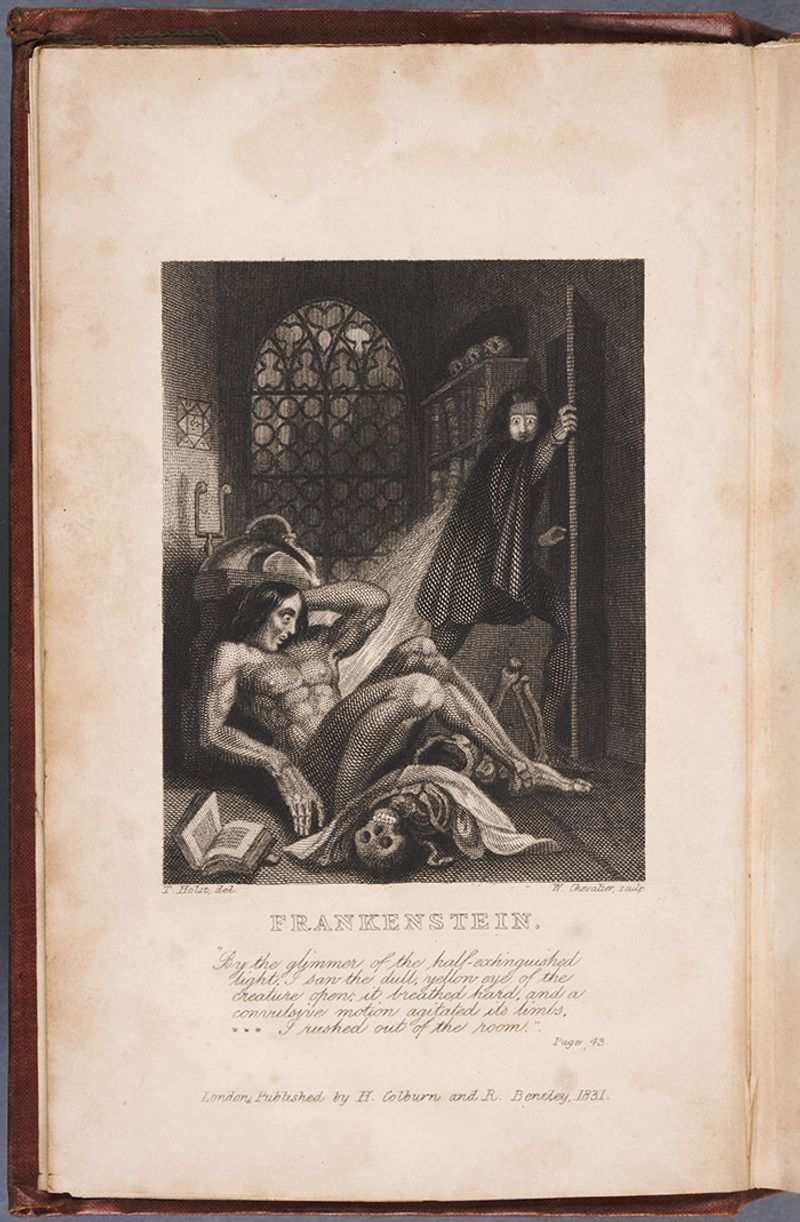

3. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1818)

Written when Shelley was just 18 years old, this groundbreaking novel emerged from a ghost story competition during a rainy summer at Lake Geneva. The tale follows Victor Frankenstein, whose scientific ambitions lead him to create a living being from dead tissue—with catastrophic results. Far deeper than mere horror, the narrative explores profound questions about creation, responsibility, and what makes us human. The creature’s eloquent narration forces readers to sympathize with his abandonment and loneliness. Often misrepresented in pop culture, the original story contains no lightning bolts or neck bolts. Instead, it presents a sophisticated meditation on ambition, isolation, and the dangerous pursuit of knowledge without ethical boundaries.

4. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851)

Initially a commercial failure, Melville’s seafaring epic has risen to become an American literary monument. Captain Ahab’s monomaniacal pursuit of the white whale represents one of literature’s most complex character studies. Beyond the famous revenge plot, the novel serves as an encyclopedic exploration of 19th-century whaling. Melville alternates between thrilling narrative and detailed chapters on whale anatomy, maritime customs, and philosophical musings. The famous opening line—”Call me Ishmael”—introduces a narrative voice that shifts between adventure tale, scientific treatise, and cosmic meditation. Its ambitious scope and symbolic depth continue to challenge and reward readers willing to navigate its occasionally demanding passages.

5. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847)

Revolutionary for its time, this gothic romance follows the orphaned Jane from childhood abuse to independence as a governess at mysterious Thornfield Hall. Her employer, the brooding Rochester, challenges Jane’s principles when their growing attraction collides with his dark secret. Brontë’s first-person narration was groundbreaking, allowing readers direct access to a plain heroine’s passionate inner life. The famous declaration—”I am a free human being with an independent will”—embodies the novel’s feminist spirit. Despite its gothic elements and romantic plot, the story fundamentally champions personal integrity and moral courage. Jane’s refusal to compromise her values, even for love, established a new kind of heroine who values self-respect above all else.

6. Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë (1847)

Emily Brontë’s only novel shocked Victorian readers with its raw intensity and unconventional structure. The passionate, destructive relationship between Catherine Earnshaw and the foundling Heathcliff unfolds across generations on the wild Yorkshire moors. Unlike typical romances, this story presents love as a primal, almost supernatural force that transcends social boundaries and even death. The narrative’s complex framing device—stories within stories told by unreliable narrators—creates a disorienting but powerful effect. Heathcliff’s character defies simple categorization as hero or villain, embodying both romantic rebellion and cruel vengeance. The novel’s uncompromising emotional landscape and atmospheric setting have influenced countless works exploring the darker aspects of human passion.

7. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (1861)

Young orphan Pip’s journey from blacksmith’s apprentice to gentleman forms the backbone of this Victorian bildungsroman. His mysterious benefactor, obsessive Miss Havisham, and beautiful but cold Estella shape his social ambitions and moral development. Dickens masterfully weaves humor, mystery and social criticism throughout the narrative. The novel exposes the hollow nature of class pretensions while examining how wealth corrupts innocent aspirations. Unlike many Dickensian tales, the original ending was deliberately ambiguous regarding Pip and Estella’s future. Dickens later revised it to suggest a more hopeful conclusion, but both versions emphasize how Pip’s greatest expectations ultimately had nothing to do with money or status.

8. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869)

Monumental in scope, Tolstoy’s masterpiece follows five aristocratic families through Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. The sprawling narrative alternates between intimate domestic scenes and sweeping battlefield panoramas, creating an immersive portrait of early 19th-century Russian society. Central characters Pierre Bezukhov, Natasha Rostova, and Prince Andrei evolve profoundly throughout the story. Their personal journeys reflect Tolstoy’s deep interest in how individuals find meaning amid historical forces beyond their control. Despite its intimidating reputation and length (over 1,200 pages), the novel remains surprisingly accessible. Tolstoy’s clear prose, psychological insight, and philosophical musings about history’s patterns make this epic more than just a historical chronicle—it’s a profound meditation on what makes life worth living.

9. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877)

Tolstoy’s tragic masterpiece follows the doomed affair between married aristocrat Anna and the dashing Count Vronsky against the backdrop of Imperial Russian society. Their passion collides with social conventions, leading to Anna’s increasing isolation and despair. Parallel to Anna’s story runs the contrasting relationship between landowner Levin and Kitty. Their imperfect but honest marriage provides counterpoint to Anna’s destructive passion, reflecting Tolstoy’s complex moral vision. The famous opening line—”All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”—establishes the novel’s exploration of marriage and fulfillment. Tolstoy’s psychological realism and moral complexity have led many critics to consider this the greatest novel ever written.

10. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1885)

Mark Twain’s controversial masterpiece follows young Huck and escaped slave Jim down the Mississippi River on a raft. Their journey becomes both physical adventure and moral awakening as Huck confronts his conscience about helping Jim escape. Written in vernacular dialect that shocked literary circles, the novel captures the rhythms and contradictions of pre-Civil War America. Twain’s satirical eye exposes the hypocrisy of a “civilized” society that embraces slavery and religious pretension. Ernest Hemingway famously declared that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” Despite ongoing debates about its language and racial portrayals, the novel remains a cornerstone of American literature for its authentic voice and moral complexity.

11. Dracula by Bram Stoker (1897)

Stoker’s epistolary novel introduced the world’s most famous vampire through journal entries, letters, and newspaper clippings. The story follows Jonathan Harker’s nightmarish visit to Count Dracula’s Transylvanian castle and the vampire’s subsequent invasion of England. Far from the romantic figure of modern adaptations, Stoker’s Count is a genuinely terrifying predator. The novel builds suspense through its fragmented narrative structure, gradually revealing the vampire’s powers and weaknesses. Victorian anxieties about sexuality, immigration, and modernity lurk beneath the surface of this gothic tale. The novel’s enduring influence extends beyond literature into film, television, and popular culture, establishing vampire lore that continues to evolve while maintaining its connection to Stoker’s original creation.

12. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1890)

Wilde’s only novel tells the disturbing tale of a beautiful young man whose portrait ages while he remains eternally youthful. This supernatural pact allows Dorian to pursue a life of hedonistic excess without visible consequences, as his portrait bears the marks of his corruption. Published in 1890, the novel scandalized Victorian society with its homoerotic undertones and moral ambiguity. Wilde’s signature wit and epigrams pepper the text, particularly through the character of Lord Henry Wotton, whose cynical philosophy influences Dorian’s moral descent. Beyond its supernatural elements, the story explores profound themes about art, beauty, and morality. The famous preface declaring “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book” established Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy while anticipating the controversy the novel would provoke.

13. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886)

Written in just three days during a fever dream, Stevenson’s novella explores the duality of human nature through respectable Dr. Jekyll and his monstrous alter-ego, Mr. Hyde. The story unfolds as a mystery, with lawyer Utterson investigating the connection between the two seemingly separate men. The revelation that Jekyll created a potion to separate his good and evil natures tapped into Victorian anxieties about scientific advancement and moral decay. The transformation becomes increasingly uncontrollable, suggesting that suppressing our darker impulses only strengthens them. So powerful was Stevenson’s concept that “Jekyll and Hyde” entered everyday language as shorthand for split personality. The novella’s psychological insight and atmospheric portrayal of foggy London streets established it as a cornerstone of both horror and detective fiction.

14. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866)

Dostoevsky’s psychological masterpiece follows impoverished student Raskolnikov through the planning, execution, and aftermath of murdering a pawnbroker. The novel delves deep into his tortured psyche as he justifies the killing through a theory that exceptional individuals stand above conventional morality. Set in the slums of St. Petersburg, the narrative captures the feverish atmosphere of 19th-century Russian urban poverty. Raskolnikov’s intellectual arrogance gradually crumbles under the weight of his conscience and the gentle influence of Sonya, a young woman forced into prostitution to support her family. More than a murder story, the novel examines nihilism, Christianity, and redemption through suffering. Dostoevsky’s intense psychological realism and moral complexity established a new standard for the novel as a vehicle for philosophical exploration.

15. The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (1844)

Falsely imprisoned for 14 years, Edmond Dantès transforms from a naive sailor into the mysterious, wealthy Count of Monte Cristo. Armed with a fortune and new identity, he orchestrates an elaborate revenge against those who betrayed him. Dumas crafted an adventure tale of remarkable psychological depth. Each villain receives a punishment that mirrors their crime, raising questions about justice versus vengeance. Originally published as a serial, the novel features countless subplots and colorful characters across Parisian high society, Italian bandits, and Mediterranean shipping. Despite its complexity, the central revenge narrative maintains its grip throughout all 1,200 pages, making this one of literature’s most satisfying tales of wrongful imprisonment and calculated retribution.

16. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1856)

Emma Bovary’s tragic pursuit of romantic fantasies shocked 19th-century readers and landed Flaubert on trial for obscenity. Trapped in a dull marriage to a provincial doctor, Emma seeks excitement through affairs and extravagant purchases, spiraling toward inevitable disaster. Flaubert’s revolutionary approach to realism included meticulous attention to detail and a dispassionate narrative voice. He famously spent days agonizing over single sentences, creating prose of extraordinary precision. Beyond its scandalous content, the novel offers a devastating critique of romantic clichés and bourgeois pretensions. Emma’s tragedy stems not just from her adultery but from her inability to distinguish between romantic literature and reality—making this perhaps the first great novel about the dangers of novels themselves.

17. Les Misérables by Victor Hugo (1862)

Hugo’s sweeping epic follows ex-convict Jean Valjean’s moral journey against the backdrop of post-Revolutionary France. After a bishop’s act of mercy transforms him, Valjean dedicates himself to helping others while evading the relentless Inspector Javert. Far more than the musical adaptation suggests, the original novel contains extensive historical digressions and social commentary. Hugo dedicates entire chapters to the Battle of Waterloo, Parisian sewers, and convent life, creating a panoramic vision of French society. At its heart lies a profound exploration of justice, redemption, and human dignity. The antagonism between Valjean and Javert represents competing worldviews—one believing in the possibility of moral transformation, the other in rigid adherence to law—making this not just a historical novel but a timeless meditation on compassion versus legalism.

18. The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850)

Set in 17th-century Puritan Boston, Hawthorne’s moral drama centers on Hester Prynne, forced to wear a scarlet ‘A’ for adultery while refusing to name her child’s father. The secret identity of her lover—the town’s respected minister—and her estranged husband’s quest for revenge drive the psychological tension. The novel’s symbolic richness extends beyond the famous letter to include the wild forest, the town scaffold, and Hester’s daughter Pearl. Hawthorne’s ambiguous treatment of sin and redemption challenges the Puritan moral code while exploring universal themes of guilt, shame, and identity. Revolutionary for its time, the story sympathetically portrays a female protagonist who maintains dignity despite public humiliation. Hawthorne’s psychological depth and moral complexity established American literature as capable of sophisticated artistic expression distinct from European traditions.

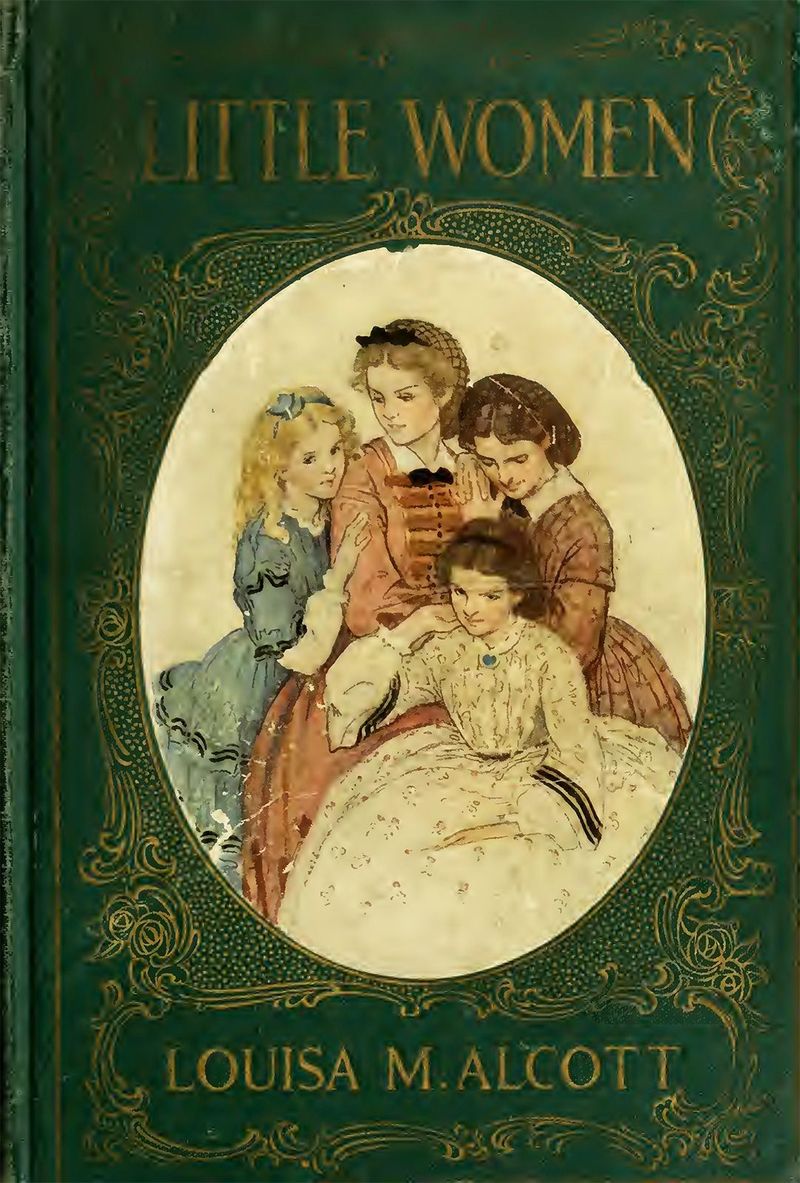

19. Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868)

Based partly on Alcott’s own childhood, this beloved coming-of-age story follows the four March sisters—practical Meg, tomboyish Jo, gentle Beth, and artistic Amy—as they navigate adolescence during the Civil War. Their mother guides them through poverty, illness, and heartbreak while their father serves as a Union chaplain. Jo March, with her literary ambitions and resistance to traditional gender roles, became one of literature’s most enduring heroines. Her decision to prioritize her writing over marriage was revolutionary for its time, though Alcott eventually gave her a compatible partner. The novel balances sentimental elements with surprising moral complexity. Alcott’s portrayal of domestic life elevated “women’s concerns” to literary significance, creating a timeless portrait of family bonds and female ambition that continues to inspire adaptations across generations.

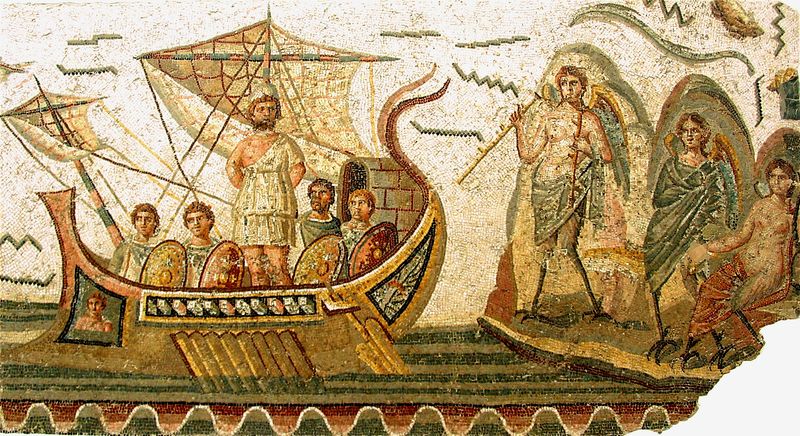

20. The Odyssey by Homer (8th century BC)

The original epic adventure follows Greek hero Odysseus’s ten-year journey home after the Trojan War. Facing one-eyed giants, seductive enchantresses, and vengeful gods, he struggles to return to his faithful wife Penelope and son Telemachus in Ithaca. Composed nearly 3,000 years ago and transmitted orally before being written down, the poem contains remarkable psychological insight. Odysseus’s defining trait—his cunning intelligence—repeatedly saves him, though his pride sometimes creates new obstacles. Beyond its exciting adventures, the epic explores profound themes of homecoming, identity, and civilization versus savagery. Its influence extends through Western literature from Virgil to Joyce, establishing narrative patterns still recognizable in modern stories of journey and return—making it perhaps the oldest work that still reads as recognizably human.