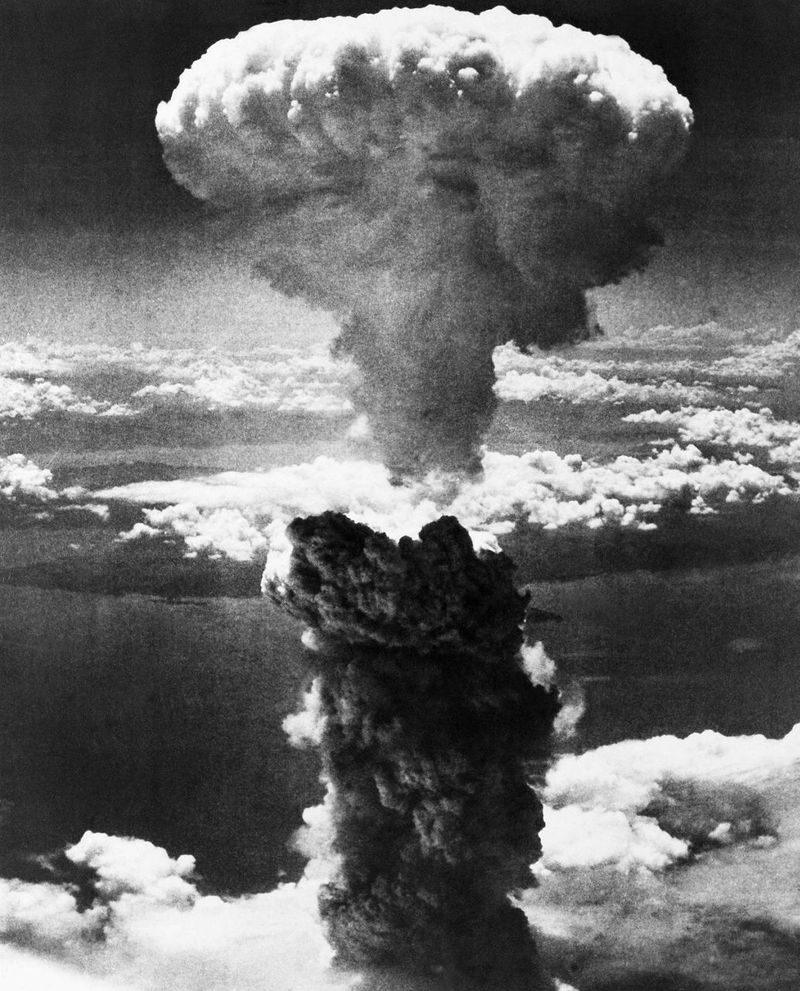

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 marked the end of World War II, but left behind many unanswered questions. These devastating attacks killed thousands instantly and affected generations through radiation.

While history books often present a straightforward narrative about why America dropped these bombs, many aspects of these events remain puzzling or contradictory when examined closely.

1. Soviet Union’s Entry May Have Been More Decisive

When the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 8, 1945, it created a shocking new reality for Japanese leaders. Their strategy had hinged on using the neutral Soviets as mediators for better surrender terms with the Allies.

The Soviet invasion of Manchuria happened with lightning speed, threatening a two-front war Japan couldn’t possibly win. Many historians now believe this Soviet action, not the atomic bombs, was what truly forced Japan’s surrender.

Japanese military leaders had prepared to endure conventional bombing, but the prospect of fighting both America and the Soviet Union made their position hopeless.

2. Japan Was Already Close to Surrender

Military intelligence from summer 1945 showed Japan was nearly defeated. Their navy was destroyed, air force crippled, and civilians were starving under blockades.

Several high-ranking American military leaders, including General Dwight Eisenhower and Admiral William Leahy, openly questioned the need for atomic weapons. They believed conventional bombing combined with naval blockades had already brought Japan to its knees.

The Japanese government had been sending peace feelers through diplomatic channels for months. Their main condition? Preserving the Emperor’s position – a condition America ultimately accepted anyway after the bombings.

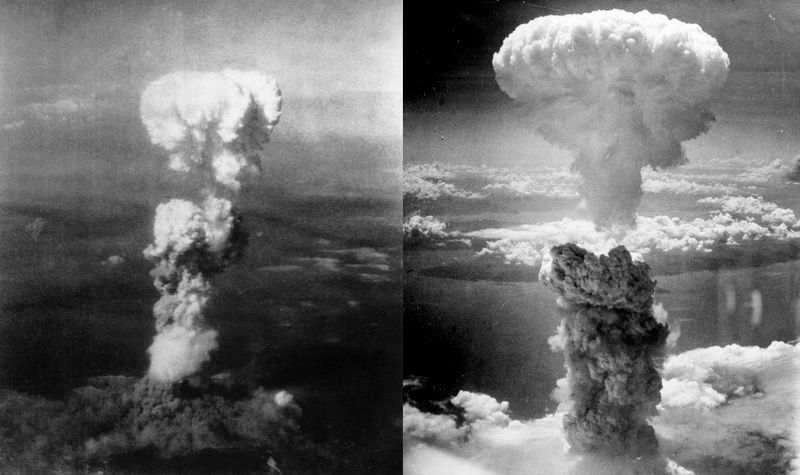

3. Nagasaki Was Never Supposed to Be Bombed

The original target for the second atomic bomb was actually Kokura, not Nagasaki. On that fateful August 9th morning, American B-29 bomber Bockscar circled Kokura three times, searching for a visual opening.

Cloud cover and smoke from previous bombings obscured the pilots’ view. Low on fuel and facing mechanical issues, the crew made the snap decision to divert to their secondary target: Nagasaki.

The bombing that killed over 70,000 people happened by chance. Had the weather been different that day, an entirely different Japanese city would have faced nuclear devastation.

4. U.S. Authorities Hid Radiation Effects

Following the bombings, American occupation authorities seized medical reports and censored Japanese doctors’ findings about radiation sickness. Journalists were forbidden from reporting on these mysterious illnesses affecting survivors.

The U.S. established the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission to study radiation effects, but oddly, it provided no medical treatment to victims. Many survivors faced discrimination and struggled to receive proper medical care.

This information blackout lasted years, preventing global understanding of radiation dangers. When John Hersey’s “Hiroshima” finally revealed these horrors to American readers in 1946, many were shocked by details that had been deliberately suppressed.

5. Targeting Civilians Violated Military Codes

The bombings killed approximately 210,000 civilians – mostly women, children, and the elderly. Military targets comprised a tiny fraction of the destruction, raising profound ethical questions about intentionally targeting non-combatants.

America’s own military code prohibited the deliberate targeting of civilians. The 1907 Hague Convention, which the U.S. signed, explicitly forbade attacking undefended towns and killing surrendered combatants.

Many bombing victims were Korean forced laborers and American POWs held in Hiroshima. The decision to target densely populated civilian areas rather than purely military installations continues to trouble ethicists and historians.

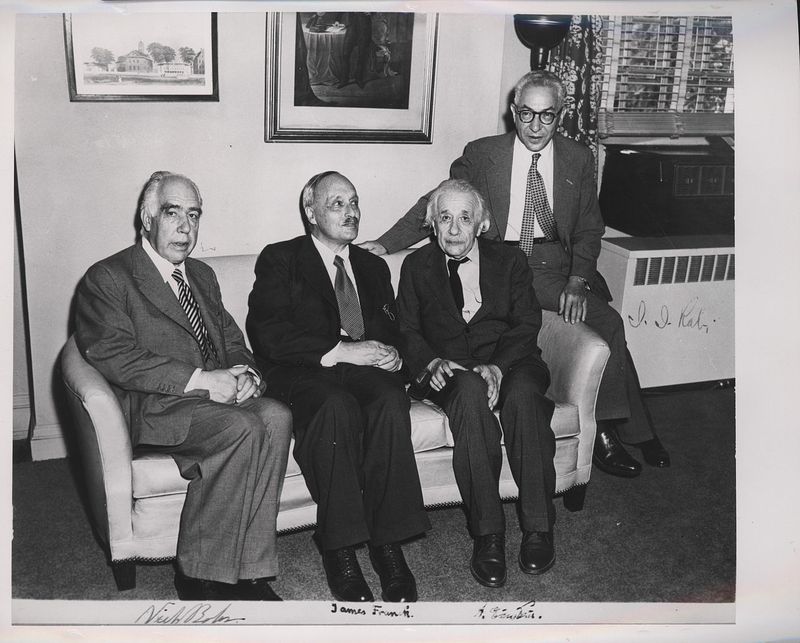

6. Scientists Proposed a Harmless Demonstration Instead

A remarkable document called the Franck Report, written by nuclear scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project, urged demonstrating the bomb on an uninhabited island with Japanese observers present. They believed this would shock Japan into surrender without killing civilians.

Leo Szilard, who helped create the bomb, gathered 70 scientist signatures on a petition opposing its use against Japan. These scientists feared starting a nuclear arms race and believed a non-lethal demonstration would achieve surrender.

These alternative proposals never reached President Truman’s desk. Military leaders dismissed them, believing only actual destruction would convince Japan to surrender unconditionally.

7. The Rush to Use Bombs Before Peace Negotiations Succeeded

The timing of the bombings raises troubling questions. America intercepted Japanese diplomatic cables indicating their willingness to surrender if allowed to keep their Emperor – a condition America ultimately accepted anyway.

Rather than waiting for these peace overtures to develop, the bombings were rushed. The Potsdam Declaration demanding Japan’s surrender was issued on July 26, giving them minimal time to respond before the August 6 bombing.

Some historians suggest the hurry stemmed from wanting to use the weapons before peace negotiations succeeded. Others point to America’s desire to demonstrate nuclear power to the Soviets as the Cold War tensions were already emerging.

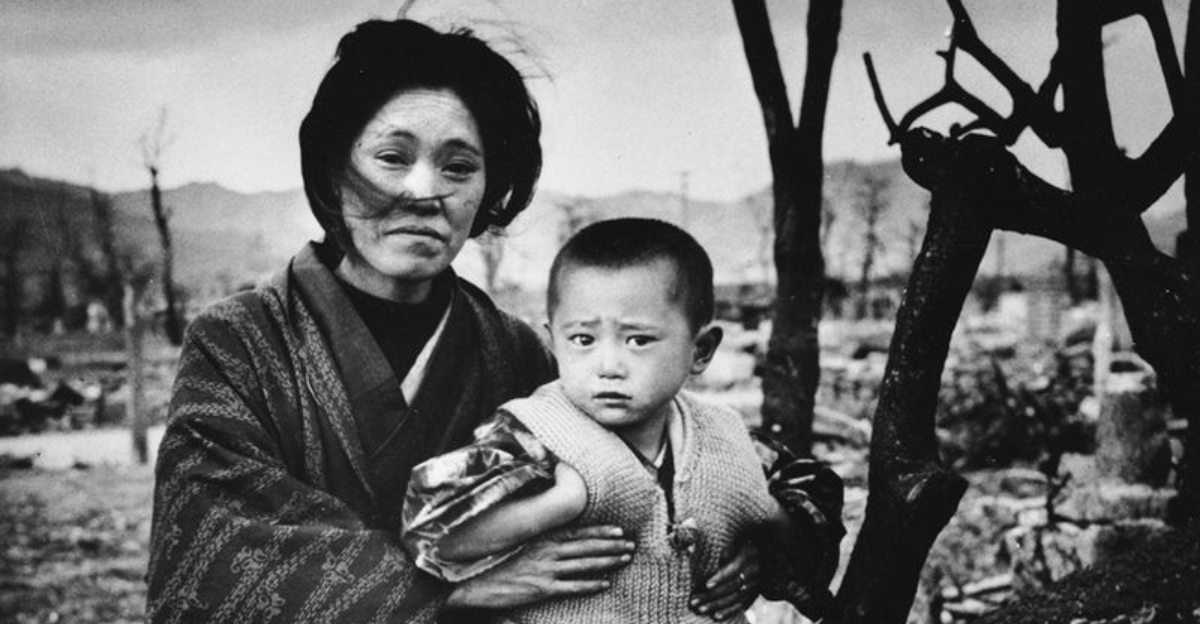

8. Survivors Faced Decades of Discrimination

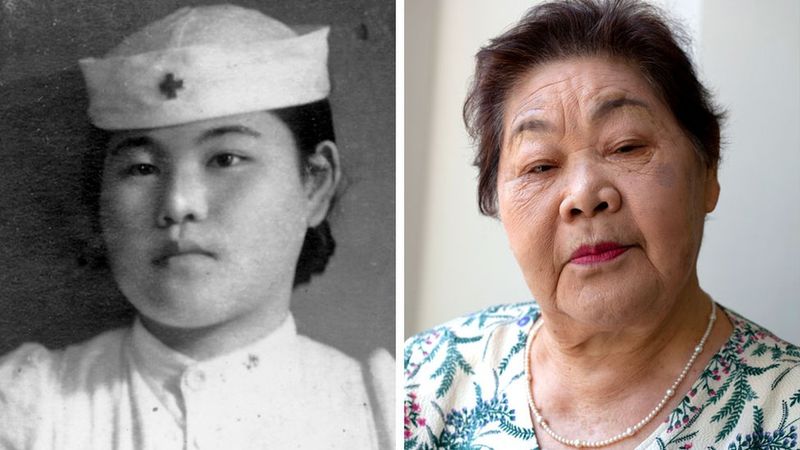

The hibakusha (bomb survivors) encountered shocking discrimination from fellow Japanese citizens. Many couldn’t find jobs or marriage partners due to fears their radiation exposure caused genetic damage.

Women survivors particularly suffered, facing rejection as potential wives and mothers. Insurance companies refused coverage, and employers turned them away, forcing many into poverty and isolation.

The Japanese government didn’t provide medical support until 1957 – twelve years after the bombings. Even today, second and third-generation survivors report discrimination, though no scientific evidence shows genetic damage passed to children of survivors.