Robin Hood, the legendary outlaw of Sherwood Forest, has captivated our imaginations for centuries.

His tales of robbing the rich to give to the poor have inspired countless books, movies, and even video games.

But how much of what we think we know about this hooded hero is actually true? Let’s separate fact from fiction in the Robin Hood legend.

1. A Legend Born From Many Men

Historians believe Robin Hood wasn’t just one person but a character inspired by several real-life outlaws. Medieval court records mention multiple criminals using “Robinhood” as a nickname or alias. This explains why the legend has so many contradictory elements—different stories were merged over centuries to create the character we know today. The Robin Hood we celebrate is essentially a medieval patchwork hero!

2. Medieval Celebrity Since the 1200s

Robin Hood’s name first appears in English court records around 1261, when a fugitive called “William son of Robert le Fevre” was referred to as “William Robehod.” By 1300, “Robinhood” had become shorthand for outlaws. These early mentions prove the legend is truly ancient, predating even Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The name was so well-known that criminals would sometimes adopt it, similar to modern bank robbers calling themselves “Robin Hood.”

3. Humble Beginnings as a Commoner

Forget the nobleman backstory—early Robin Hood ballads describe him as a yeoman, a free-born commoner who owned land. This ordinary status made him more relatable to medieval audiences who enjoyed tales of clever commoners outsmarting corrupt officials. Only in the 1500s did writers begin portraying him as a fallen aristocrat. The transformation reflected changing social dynamics and literary tastes that favored noble protagonists over peasant heroes.

4. Sherwood Forest Still Stands Today

While dramatically smaller now, parts of the legendary Sherwood Forest survive in Nottinghamshire, England. The forest once covered over 100,000 acres but now spans just 1,045 acres. The remaining woodland contains the famous Major Oak, a massive 1,000-year-old tree that, according to folklore, served as Robin Hood’s hideout. Modern visitors can walk trails where the legendary outlaw supposedly roamed, though they’ll need to imagine the vast medieval wilderness it once was.

5. The Real Sheriff of Nottingham

The position of Sheriff of Nottingham genuinely existed during the 12th and 13th centuries. These royal officials collected taxes and enforced the king’s laws—making them natural villains in outlaw tales. Philip Mark, Sheriff from 1209-1224, was particularly unpopular. As a foreigner appointed by King John, he embodied the corrupt official archetype. While no historical sheriff can be definitively linked to Robin Hood, their real-world power and frequent abuses provided perfect antagonists for the legend.

6. Crusader Connections Remain Dubious

The popular image of Robin Hood as Richard the Lionheart’s loyal crusader has little historical backing. This storyline first appeared in the 1500s, centuries after the earliest Robin Hood tales. Medieval ballads make no mention of crusades or Richard’s captivity. The crusader backstory was likely added to create a patriotic dimension to the legend during Tudor times when English identity was being redefined. Historical timing makes the crusader connection problematic, as the earliest Robin Hood references don’t align with crusade dates.

7. Voice of the Oppressed

Robin Hood emerged as a powerful symbol during times of extreme social inequality. His legend gained popularity following the devastating Black Death when new laws restricted peasant wages despite labor shortages. The Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 showed real-world parallels to Hood’s fictional rebellion. His stories provided catharsis for the oppressed who couldn’t openly challenge authority. The outlaw’s defiance of corrupt officials resonated with commoners suffering under harsh taxation and unjust forest laws.

8. The Original Outlaw Was No Hero

Early Robin Hood wasn’t the noble hero we recognize today. In medieval ballads like “Robin Hood and the Monk” (c.1450), he murders a monk simply for recognizing him, then kills the monk’s young servant to silence any witnesses. These original stories portrayed him as violent, quick-tempered, and self-interested. He primarily targeted corrupt clergy and officials, not out of pure altruism, but personal vendettas. Medieval audiences enjoyed these darker tales of brutal justice against institutions they resented.

9. Charitable Reputation Came Later

The famous “rob from the rich, give to the poor” motto wasn’t part of early Robin Hood tales. This charitable aspect evolved gradually during the 15th and 16th centuries as the character became more romanticized. In early ballads, Robin occasionally helps commoners, but just as often keeps plunder for himself and his men. The transformation into a full-fledged champion of the poor reflects changing social attitudes and literary trends. By Victorian times, his generosity had become his defining trait, completely overshadowing his earlier selfish tendencies.

10. Final Resting Place Claims

Robin Hood’s supposed grave sits on private land near Kirklees Priory in West Yorkshire. According to legend, the dying outlaw shot an arrow from the priory window, asking to be buried where it landed. The grave marker dates to the 18th century but claims to replace an earlier stone. Various historical accounts place his death around 1247, though this conflicts with other origin stories. The site remains controversial among historians, with some believing it commemorates a different local figure who adopted the famous outlaw’s name.

11. His Iconic Green Outfit Is Modern

Robin Hood’s famous bright green outfit wasn’t part of the original legend. Early descriptions rarely mention his clothing color at all. The “Lincoln green” costume became standardized through 16th-century plays and later solidified in Victorian literature. The bright color made theatrical characters easily identifiable on stage. Forest-dwelling outlaws would realistically have worn browns and grays for camouflage. The vibrant green we associate with Robin Hood today would have made him an easy target for the sheriff’s men!

1. Myth: One True Robin Hood

Despite countless attempts to identify the “real” Robin Hood, no single historical figure fits the bill. Various candidates have been proposed, from nobleman Robert Fitzooth to outlaw Robert Hod. The search for a definitive Robin Hood misunderstands how folklore develops. Like King Arthur, he likely began as a composite character that accumulated traits and adventures over centuries. The obsession with finding the “real” Robin Hood reveals more about our desire for historical anchoring than medieval reality.

2. Myth: Always Portrayed as a Nobleman

Modern adaptations typically present Robin as Earl of Locksley or another displaced nobleman. This aristocratic background appears nowhere in the earliest ballads, where he’s consistently described as a yeoman (free commoner). The noble origin gained popularity through 16th-century plays and Sir Walter Scott’s influential 1819 novel “Ivanhoe.” This transformation reflected changing audience preferences. While medieval commoners enjoyed stories about one of their own outwitting authorities, later audiences preferred tales of rightful nobility triumphing over temporary adversity.

3. Myth: Sherwood Forest Was His Only Home

Sherwood Forest dominates modern Robin Hood stories, but many early ballads place him in Barnsdale Forest, Yorkshire. Some tales mention both locations, suggesting he ranged across northern England. The earliest known ballad, “Robin Hood and the Monk” (c.1450), mentions Nottingham but not Sherwood specifically. Barnsdale appears more frequently in early sources. The exclusive Sherwood connection strengthened through later adaptations, particularly after tourism to Nottinghamshire increased in the 19th century.

4. Myth: Always Robbed Rich to Help Poor

The altruistic Robin Hood who steals purely to help the downtrodden is largely a modern invention. In early ballads, he primarily targets corrupt officials and wealthy clergy who personally wronged him or represented oppressive authority. Sometimes he shares plunder with the poor, but often keeps it for himself and his men. He’s portrayed as personally generous but not systematically charitable. The transformation into a selfless philanthropist developed gradually, reaching its peak in Victorian retellings that emphasized moral lessons over the outlaw’s rebellious nature.

5. Myth: King Richard’s Loyal Subject

The portrayal of Robin Hood loyally awaiting King Richard’s return from crusades contradicts historical reality. Richard I (1189-1199) spent less than six months of his 10-year reign in England, preferring his French territories and crusading. The king barely spoke English and viewed England primarily as a source of tax revenue for his military campaigns. The Richard-Robin relationship first appears in Anthony Munday’s plays (1598) and was cemented by Sir Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe” (1819). This fictional loyalty created a politically safe version of Robin who opposed corrupt officials but remained devoted to the crown.

6. Myth: Maid Marian Was Always His Love

Maid Marian doesn’t appear in any early Robin Hood ballads. She originated in separate French pastoral plays and May Day celebrations, only merging with Robin Hood stories in the 16th century. Early Robin Hood tales were masculine adventures without romantic elements. Marian’s introduction coincided with the legend’s shift from oral tradition to written literature aimed at broader audiences. Her character evolved from a shepherdess to a noblewoman, reflecting changing literary tastes. Modern adaptations have further transformed her from love interest to warrior woman.

7. Myth: Friar Tuck Among Original Companions

The jovial Friar Tuck was absent from early Robin Hood tales, first appearing in a 1475 play—centuries after the original ballads. As a comic character, he added religious satire to the legend during a time of growing church criticism. Medieval audiences would have appreciated the irony of a man of God joining outlaws. Tuck’s popularity grew through May Day festivities where his character often appeared alongside Robin Hood. His depiction as overweight and fond of food and drink became standard in the 17th century.

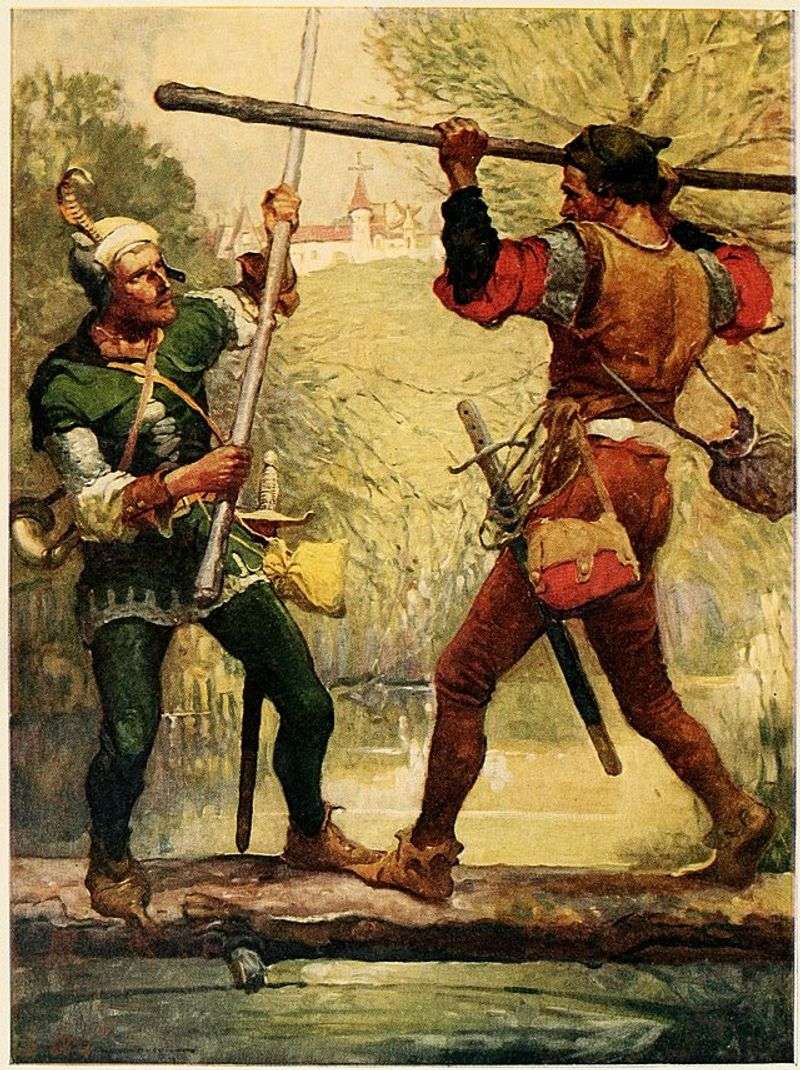

8. Myth: Bow and Arrow Only

While modern portrayals focus on Robin Hood’s archery skills, early stories show him equally adept with sword, quarterstaff, and wrestling. The famous splitting-arrow contest appears in later ballads, not the earliest tales. Medieval outlaws would have needed diverse combat skills to survive. The quarterstaff duel with Little John appears in many early stories, highlighting Robin’s skill with this common weapon. The exclusive focus on archery developed as firearms replaced bows in warfare, making arrow skills seem more romantically historical.

9. Myth: Unchanging Legend Through History

Robin Hood’s character has transformed dramatically across centuries, shaped by each era’s social concerns. Medieval ballads portrayed a violent trickster targeting corrupt clergy during church power struggles. Tudor versions emphasized his noble birth during a time of social mobility anxiety. Victorian retellings sanitized his violence and stressed charity when class tensions were high. During the Great Depression, he became a socialist hero, while Cold War versions emphasized his fight for freedom against tyranny. Each generation reinvents Robin Hood to address contemporary issues.

10. Myth: Always the Perfect Hero

Long before Robin became the perfect gentleman-thief, early ballads portrayed him as morally complex and often brutal. He kills travelers who refuse to pay for passage through his forest and murders unarmed men who could identify him. In “Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne,” he beheads his enemy and mutilates the corpse. These darker elements disappeared as the legend became children’s entertainment. The sanitization accelerated in Victorian times when Robin Hood stories were repurposed as moral tales for young readers.