Words can wound as deeply as any weapon, and history’s sharpest minds have wielded wit like a sword. From literary giants to political figures, the art of the elegant insult has been perfected across centuries. These verbal jabs have outlived their creators, remembered not just for their sting but for the clever wordplay that makes us wince and laugh simultaneously.

1. William Shakespeare (Troilus and Cressida, 1602): “Thou sodden-witted lord! Thou hast no more brain than I have in mine elbows.”

The Bard of Avon wasn’t just a master of romance and tragedy – he could skewer opponents with linguistic precision. This particular barb appears in his problem play about the Trojan War, where Ajax is being mocked for his dullness. Shakespeare essentially calls the recipient soggy-brained and compares his intelligence to that of an elbow – a body part not known for its thinking capacity. The insult works on multiple levels, combining the visceral image of a wet, mushy brain with the absurdity of an intelligent elbow. Four centuries later, we’re still quoting his creative put-downs.

2. Alexander Pope (An Essay on Criticism, 1711): “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.”

Alexander Pope crafted this enduring insult to mock reckless critics who judge literature without proper understanding. The line has transcended its original context to become a universal condemnation of hasty, uninformed action. Pope’s genius lies in contrasting the fool’s impulsive behavior with an angel’s divine wisdom and caution. The phrase employs religious imagery to heighten the contrast between ignorance and wisdom. This elegant put-down has been repurposed countless times in literature, music, and everyday speech, proving that sometimes the most devastating insults become cultural touchstones.

3. Voltaire (Letter to Frederick the Great, 1755): “The Holy Roman Empire is neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.”

French philosopher Voltaire delivered this surgical strike against an entire political entity. His three-part dismantling of the Holy Roman Empire’s very name reveals his talent for exposing absurdity through logic. Writing to Frederick the Great of Prussia, Voltaire used just nine words to completely delegitimize a powerful European institution. Each denial strips away another layer of the empire’s grandiose self-image. The insult’s brilliance lies in its simplicity and comprehensiveness – it doesn’t attack individuals but undermines the very foundation of the entity’s identity and claims to authority.

4. Samuel Johnson (attributed, c. 1763): “Sir, you have not the most distant idea how much I despise you.”

Dr. Johnson, dictionary compiler and literary giant, didn’t mince words when expressing contempt. This cutting remark suggests the recipient’s understanding is so limited they can’t even grasp the depth of Johnson’s disdain. The beauty of this insult lies in its elegant construction – it’s not merely saying “I despise you” but adding an extra layer by claiming the target is too stupid to comprehend just how much they’re despised. Johnson creates a double insult: contempt wrapped in an accusation of ignorance. His formal address (“Sir”) adds a veneer of civility that makes the blow land even harder.

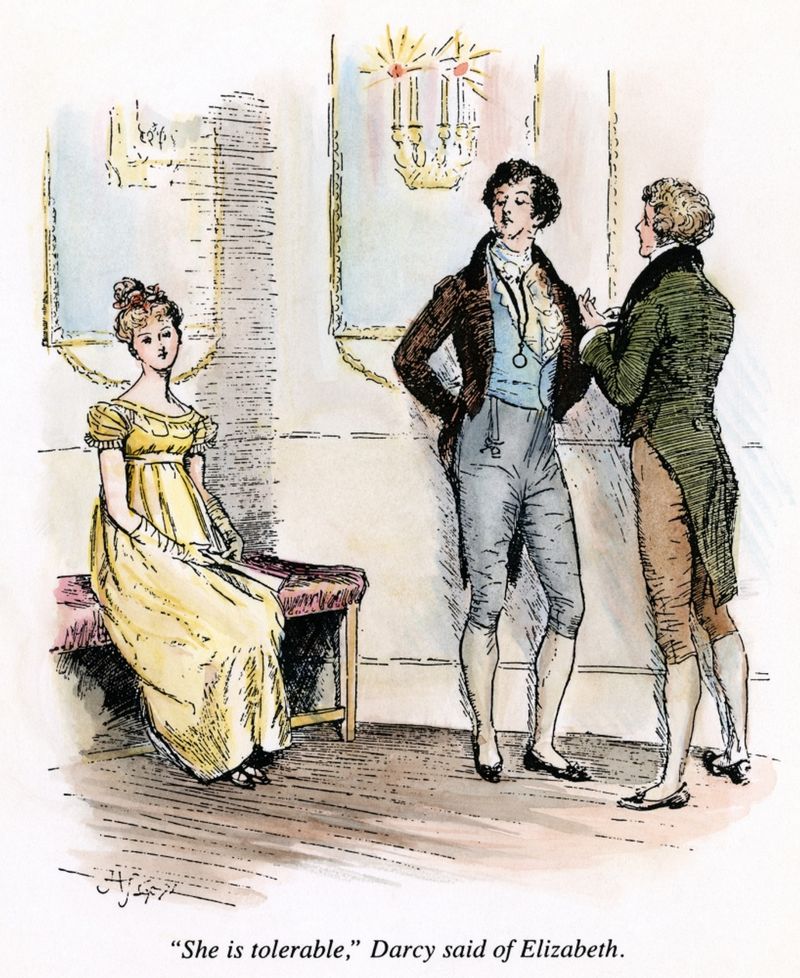

5. Jane Austen (Pride and Prejudice, 1813) Mr. Darcy on Miss Bingley: “She is tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me.”

Austen’s famous romantic hero begins as anything but charming with this devastating assessment of Elizabeth Bennet. The insult brilliantly establishes Darcy’s character – proud, aloof, and judgmental – while simultaneously setting up the novel’s central relationship conflict. What makes this barb particularly cutting is that it’s overheard by its target, Elizabeth, who wasn’t meant to hear such casual cruelty. The word “tolerable” damns with faint praise, suggesting bare minimum acceptability. Austen packs societal commentary into this brief exchange, highlighting the marriage market’s superficiality and the power dynamics between men and women in Regency England.

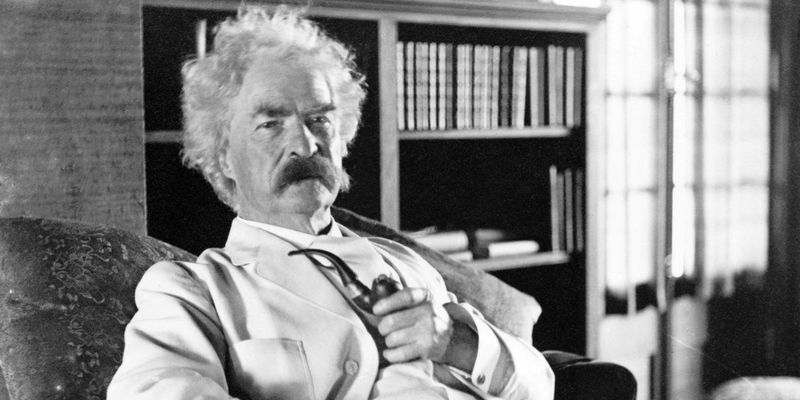

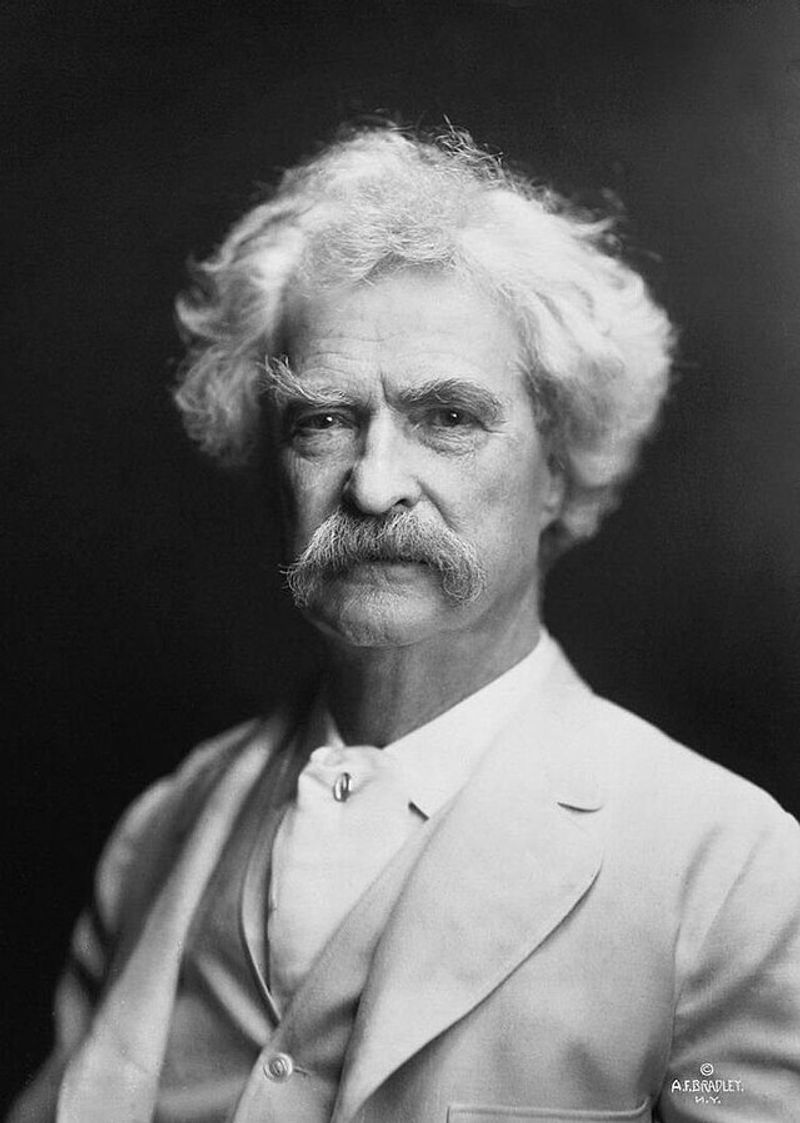

6. Mark Twain (letter, 1894): “I didn’t attend the funeral, but I sent a nice letter saying I approved of it.”

America’s premier humorist delivered this perfectly crafted insult about an unnamed enemy’s death. Twain manages to express satisfaction at someone’s passing while maintaining a veneer of social propriety through the “nice letter” mentioned. The brilliance lies in its casual delivery – as if approving of someone’s death is perfectly normal. Twain doesn’t waste energy on elaborate metaphors or flowery language. Instead, he opts for straightforward brutality wrapped in everyday conversation. This quote exemplifies Twain’s trademark style: seemingly simple language delivering a devastating blow with perfect comedic timing.

7. Oscar Wilde (Lady Windermere’s Fan, 1892): “Some cause happiness wherever they go; others whenever they go.”

Wilde’s razor-sharp wit shines in this perfectly balanced insult. The parallel structure creates an expectation in the first half, then delivers a surprising twist that completely reverses the meaning. The genius of this barb is its versatility – it can be applied to almost anyone without modification. Wilde doesn’t attack specific traits but instead creates a universal template for dismissing someone’s entire presence as unwelcome. The insult maintains Wilde’s characteristic lightness of tone while delivering a devastating message: some people improve a situation simply by leaving it. Few writers could match his ability to be simultaneously charming and brutal.

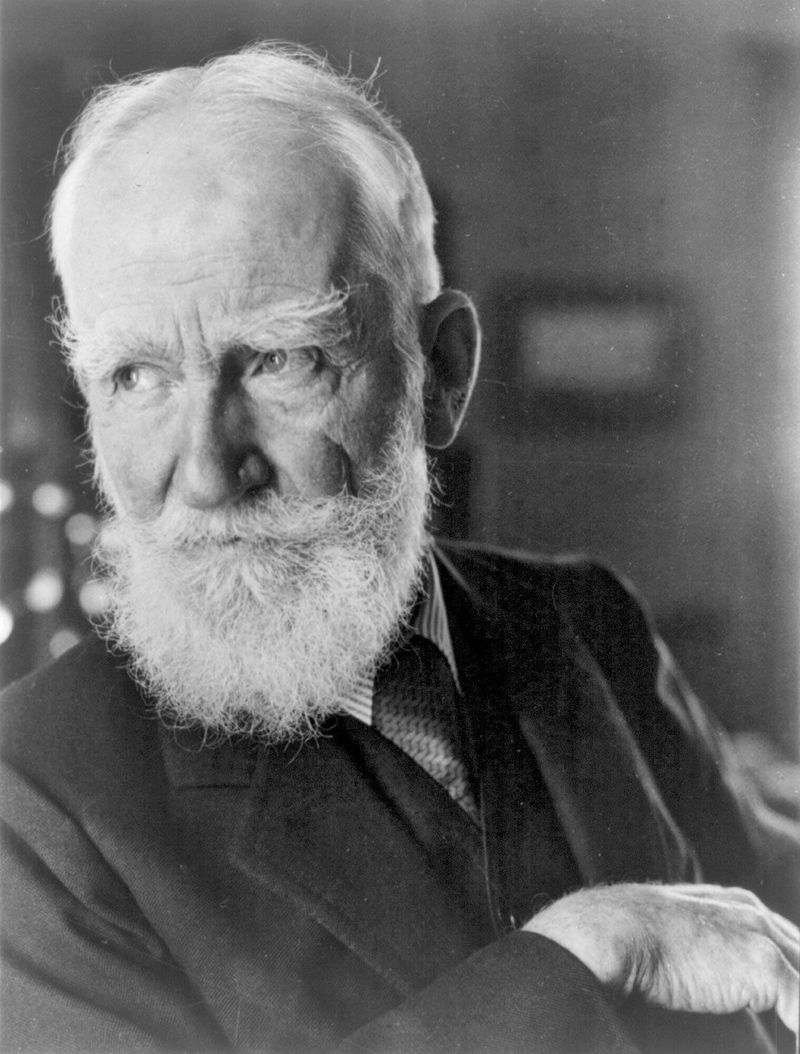

8. George Bernard Shaw (Maxims for Revolutionists, 1903): “He knows nothing; and he thinks he knows everything. That points clearly to a political career.”

Shaw’s withering assessment of politicians has remained painfully relevant for over a century. This two-part insult first establishes the target’s complete ignorance, then adds the devastating twist that this person believes themselves omniscient. The brilliance comes in the conclusion – linking this specific combination of ignorance and arrogance to political ambition. Shaw doesn’t merely insult an individual but an entire profession, suggesting politics naturally attracts the confidently clueless. As a playwright and social critic, Shaw specialized in exposing societal hypocrisies, and this particular barb continues to resonate across political eras and systems.

9. Theodore Roosevelt (attributed, early 1900s): “If you could kick the person in the pants responsible for most of your trouble, you wouldn’t sit for a month.”

Roosevelt delivers a profound truth wrapped in homespun wisdom with this self-directed insult. Unlike most entries on this list, this barb isn’t aimed at others but serves as a wake-up call to recognize our own responsibility for our problems. The imagery is comically physical – a literal kick to one’s own behind. Roosevelt, known for his vigorous personality and direct speech, uses this folksy metaphor to deliver a sophisticated message about personal accountability. The quote’s genius lies in its versatility; it can be used as gentle self-deprecation or as a pointed reminder to someone blaming others for their misfortunes.

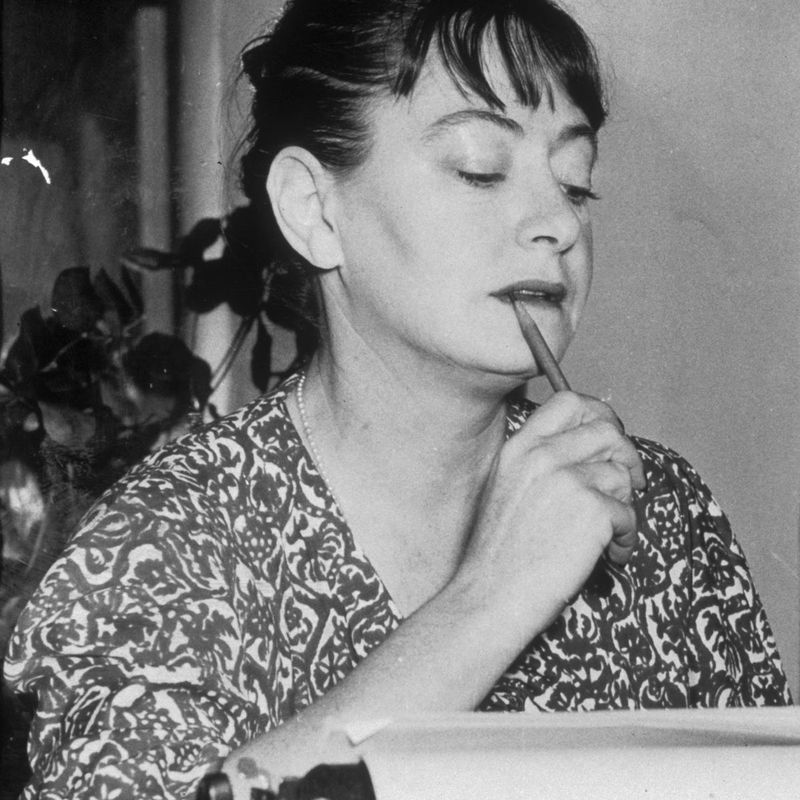

10. Dorothy Parker (The Portable Dorothy Parker, 1944): “You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think.”

Parker’s legendary wordplay transforms the familiar saying about horses and water into a brilliant pun mocking educated but unintelligent women. The setup leads listeners to expect “horse” but delivers “horticulture” instead, creating both surprise and delight. This verbal sleight-of-hand demonstrates Parker’s linguistic dexterity and quick wit. The insult works on multiple levels – it’s a clever play on words while simultaneously delivering a cutting commentary on education without intelligence. Parker reportedly delivered this line during a word game at a party, showcasing her ability to craft memorable insults spontaneously – a talent that made her both beloved and feared in literary circles.

11. Winston Churchill (letter to Lady Astor, 1915): “He has all the virtues I dislike and none of the vices I admire.”

Churchill’s masterful inversion creates an insult that seems like a compliment until examined closely. Rather than attacking someone for being immoral, he criticizes them for possessing the wrong kind of morality – a far more sophisticated critique. The brilliance lies in Churchill’s admission of his own questionable values, which somehow makes the insult even more devastating. He’s not claiming moral superiority but suggesting the target is boring and lacks character despite their technical virtues. This perfectly balanced sentence shows Churchill’s linguistic precision and his ability to craft insults that reveal more about human nature than simple attacks ever could.

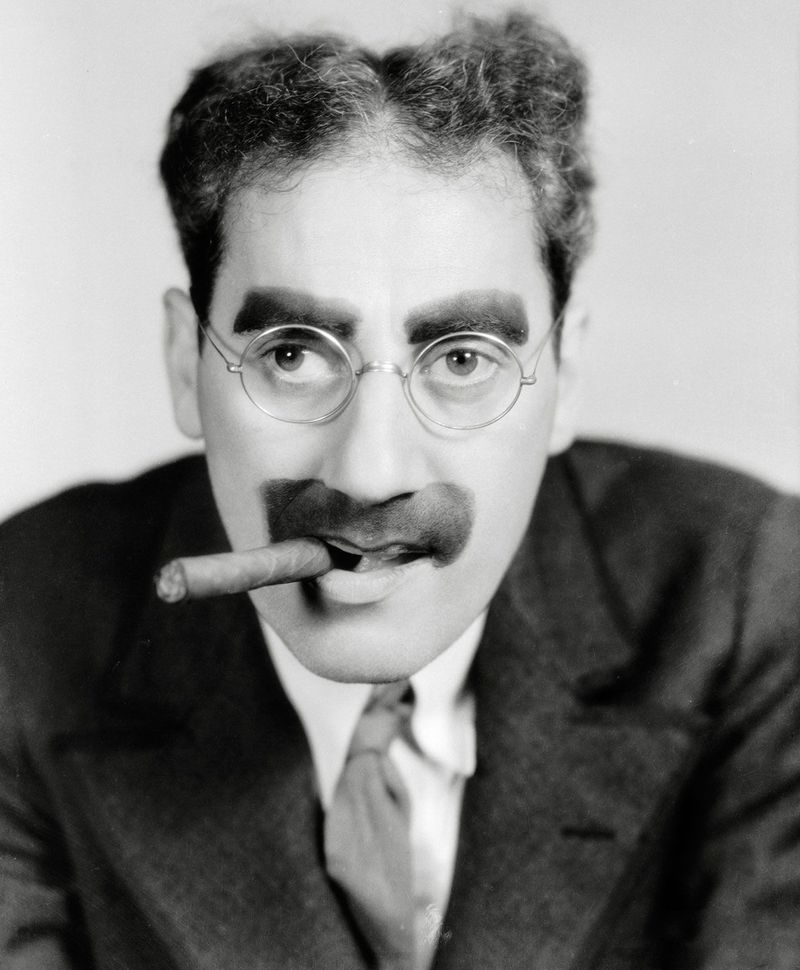

12. Groucho Marx (Groucho and Me, 1959): “I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member.”

Marx’s self-deprecating quip functions as both personal insult and social commentary. At first glance, it’s a joke at his own expense – suggesting he’s so worthless that any club accepting him must have low standards. Looking deeper, the paradox reveals a critique of social hierarchies and exclusivity. Marx questions the value of belonging to groups that judge worthiness based on arbitrary criteria. The line’s genius comes from its philosophical depth disguised as a throwaway joke. While making audiences laugh, Marx simultaneously explored concepts of identity, belonging, and social validation – proving comedy could be both accessible and intellectually profound.

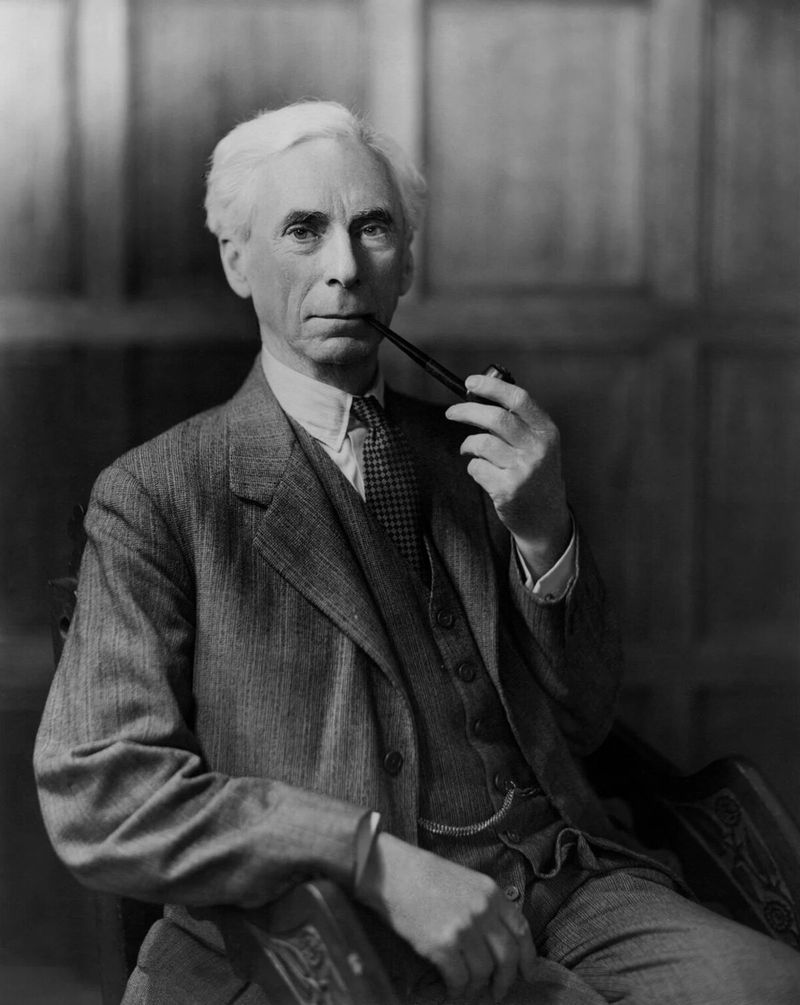

13. Bertrand Russell (Marriage and Morals, 1929): “An idealist is one who, on noticing that roses smell better than a cabbage, concludes that it will also make better soup.”

Russell’s philosophical barb uses a clever food metaphor to skewer impractical idealism. The comparison between roses and cabbage creates an instantly recognizable image that makes complex philosophical criticism accessible. The insult works by highlighting the logical fallacy of assuming that something superior in one context will be superior in all contexts. Russell, a mathematician and philosopher, had little patience for fuzzy thinking, making this critique particularly representative of his intellectual approach. While gentler than many entries on this list, the insult’s effectiveness lies in how it undermines an entire worldview through a simple, everyday example that anyone can understand.

14. H. L. Mencken (A Book of Prefaces, 1917): “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.”

Mencken’s biting critique of democracy manages to insult both the system and the citizenry simultaneously. The first half seems straightforward enough, but the addition of “good and hard” transforms it into something more sinister – suggesting that voters’ choices will become their punishment. Known as the “Sage of Baltimore,” Mencken specialized in deflating American political idealism with sardonic observations. This particular barb exemplifies his talent for crafting phrases that initially appear to be simple statements but reveal their sting in the final words. The insult’s enduring power comes from its uncomfortable proximity to truth in any democratic society.

15. Mae West (She Done Him Wrong, 1933): “I generally avoid temptation unless I can’t resist it.”

West’s seductive paradox serves as both a boast and a mockery of moral hypocrisy. The contradiction between “avoiding” and “can’t resist” creates a delicious tension that embodies her provocative persona. Unlike many insults that attack specific targets, West’s barb undermines the entire concept of moral restraint. She essentially admits to having no actual principles – just temporary barriers that crumble under desire. The brilliance lies in how West delivers criticism wrapped in confession. By openly embracing what society condemned as female moral weakness, she exposes the absurdity of sexual double standards while maintaining her characteristic playfulness.

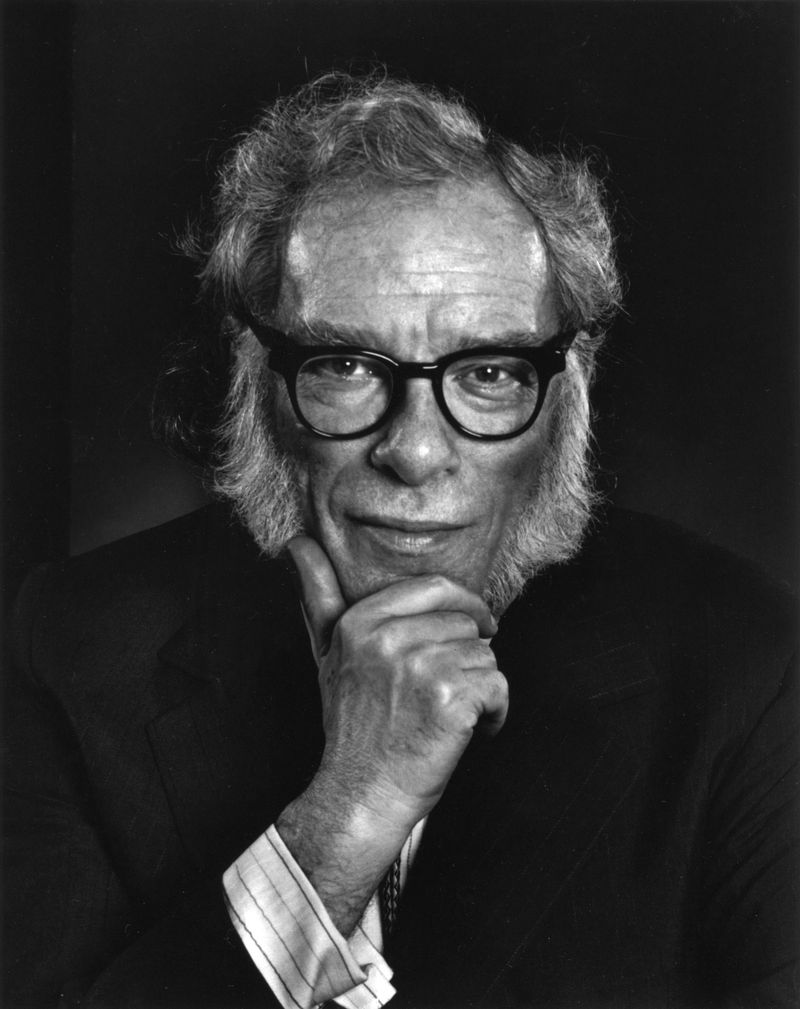

16. Isaac Asimov (attributed, mid-20th century): “His ignorance is encyclopedic.”

Asimov, master of science fiction and prolific non-fiction writer, crafted this elegant paradox to describe comprehensive ignorance. The contradiction between “ignorance” and “encyclopedic” creates immediate cognitive dissonance – encyclopedias represent complete knowledge, yet here one contains nothing but gaps. The insult suggests not simple ignorance but a thorough, almost impressive completeness to the person’s lack of knowledge. It implies they’ve achieved something remarkable – being uninformed about virtually everything. Coming from Asimov, who authored or edited over 500 books across numerous subjects, this barb carried special weight – few were better positioned to recognize the truly comprehensive dimensions of someone else’s ignorance.

17. Marie Antoinette (attributed, 1789): “Let them eat cake.” (Supposedly on hearing the poor had no bread—an insult to their poverty.)

Though historians doubt Marie Antoinette ever uttered these words, this phrase has become the ultimate symbol of aristocratic callousness toward suffering. The supposed comment reveals a catastrophic disconnect between ruler and ruled – suggesting frivolous luxury (cake) as a solution to starvation. The insult’s power comes from its casual cruelty. Whether historically accurate or not, these four words encapsulated an entire society’s grievances against the privileged elite who couldn’t comprehend basic survival challenges. The quote’s lasting impact demonstrates how a simple insult can become a revolutionary catalyst, eventually helping to topple a monarchy and change the course of history.

18. Dorothy Parker (Vicious Circle, 1939): “I wish I had a twin, so I could know what I’d look like without any plastic surgery.”

Parker directs her legendary wit inward with this self-deprecating jab that simultaneously mocks Hollywood’s beauty standards. The line appears self-critical but actually delivers a clever critique of celebrity culture and cosmetic enhancement trends. The joke works through misdirection – listeners expect a standard twin fantasy but instead get an admission of surgical alterations. Parker’s ability to combine personal confession with cultural commentary made her barbs especially effective. This particular quip showcases her talent for social criticism disguised as lighthearted banter – a technique that allowed her to address sensitive subjects while maintaining her reputation as the wittiest woman in New York.

19. Winston Churchill (broadcast, 1940): “Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

Churchill’s famous description of Russia serves as a sophisticated insult disguised as political analysis. While appearing to be a neutral observation, the nested metaphor suggests Russia is deliberately incomprehensible, untrustworthy, and impossible to deal with straightforwardly. The three-layered description creates a sense of impenetrable obscurity. Churchill implies that understanding Russia requires unwrapping multiple layers of deception and confusion. The quote’s genius lies in its diplomatic packaging – it delivers harsh criticism while maintaining plausible deniability. Churchill could claim he was merely describing Russia’s complexity, not insulting its character, while actually doing both simultaneously.

20. Mark Twain (letter, 1905): “Be good and you will be lonely.”

Twain’s deceptively simple observation delivers a powerful critique of society’s moral hypocrisy. The insult targets not individuals but humanity itself, suggesting that genuine virtue isolates a person from the compromised majority. The brevity amplifies its impact – just seven words create a complete worldview. Twain implies that most social connections require moral compromise, and those unwilling to compromise find themselves alone. Written late in his life after experiencing personal tragedies and disillusionment, this quote reflects Twain’s increasingly pessimistic view of human nature. The insult’s lasting power comes from the uncomfortable truth it contains – a truth many readers recognize from their own experiences.