Syphilis, a devastating bacterial infection, has silently shaped history by affecting the minds and bodies of influential figures throughout the centuries. Before antibiotics, this disease progressed through painful stages, often ending in neurological damage and death. The following historical personalities suffered from this illness, which likely altered their behavior, creative output, and decision-making—potentially changing the course of history itself.

1. Cesare Borgia (1475–1507), Italian cardinal and statesman

The ruthless Renaissance politician contracted syphilis during his military campaigns, dramatically altering his once-handsome appearance. Contemporary accounts describe painful sores erupting across his face, forcing him to wear masks in public.

His symptoms appeared during the first documented European syphilis epidemic. Physicians attempted treatments with mercury—itself toxic and often fatal—but his health declined steadily.

The disease likely contributed to his military failures in later years as his strategic thinking became erratic. Once Pope Alexander VI’s brilliant enforcer, Borgia’s syphilitic condition may have accelerated his downfall and early death at just 31.

2. Gerard de Lairesse (1641–1711), Dutch painter and art theorist

Born with congenital syphilis passed from his mother, Lairesse’s facial features became increasingly distorted throughout his life. His nose collapsed—a telltale sign of inherited syphilis—yet he achieved remarkable acclaim as the “Dutch Poussin.”

Fellow artists sometimes mocked his appearance, but his technical brilliance overcame prejudice. His self-portraits reveal his honest confrontation with his condition.

Syphilis eventually claimed his eyesight around age 49, ending his painting career. Remarkably, he pivoted to writing influential art theory books, dictating two volumes that shaped Dutch aesthetic principles for generations.

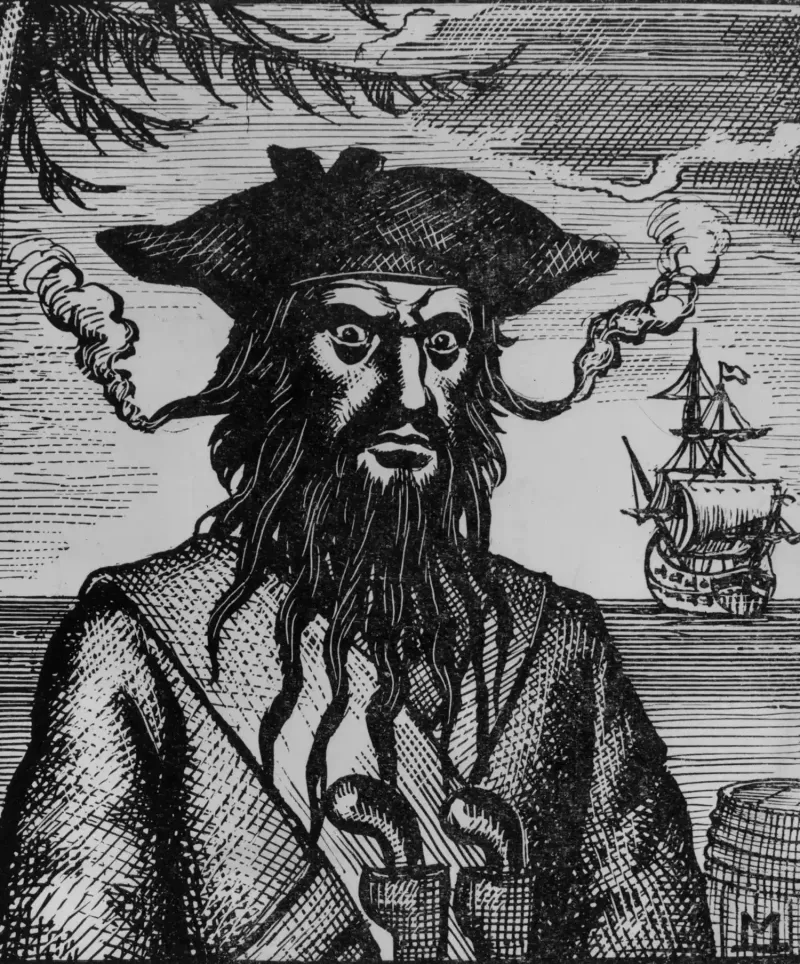

3. Edward “Blackbeard” Teach (c.1680–1718), English pirate

The fearsome pirate’s legendary temper may have been fueled by syphilitic pain. Sailors’ accounts mention his strange behaviors—raging outbursts followed by periods of lethargy that align with neurosyphilis symptoms.

Blackbeard reportedly drank gunpowder mixed with rum, possibly attempting to ease the bone-deep aches characteristic of advanced syphilis. His infamous practice of lighting fuses in his beard before battles might have served to distract from his deteriorating appearance.

Maritime records suggest he frequented Caribbean ports known for prostitution, where the disease spread rapidly among sailors. By his final battle, witnesses described him as moving awkwardly—possibly from syphilitic damage to his nervous system.

4. Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848), Italian opera composer

The brilliant mind behind “Lucia di Lammermoor” began showing syphilis symptoms in his early 40s. Friends noticed alarming personality changes—the once-gentle composer became paranoid and erratic.

His musical output became frenzied before stopping altogether. In 1845, after bizarre public behaviors, Donizetti was institutionalized in Paris. Doctors noted the classic signs of neurosyphilis: delusions, partial paralysis, and slurred speech.

The maestro who had composed 70 operas could no longer recognize his own music. His final years were spent in near-total isolation, physically paralyzed but mentally aware enough to understand his tragic decline—a heartbreaking end for one of opera’s greatest voices.

5. Franz Schubert (1797–1828), Austrian composer

Musical genius Schubert likely contracted syphilis in 1822, dramatically changing the course of his short life. His diaries record “unfathomable pain” and sudden hair loss—classic symptoms of the disease’s secondary stage.

Doctors prescribed mercury treatments that caused additional suffering: mouth ulcers, digestive agony, and trembling hands that sometimes prevented him from composing. Despite this, he created some of his most profound works while ill, including his haunting “Winterreise” song cycle.

Modern analysis of his medical records strongly suggests syphilis contributed to his premature death at 31. The illness may have influenced his late compositions’ melancholic qualities, transforming personal suffering into transcendent art.

6. Robert Schumann (1810–1856), German composer

Romantic composer Schumann’s tragic mental decline began with a syphilis infection contracted from a prostitute when he was just 21. For years, mercury treatments temporarily controlled his symptoms while slowly poisoning him.

His musical brilliance was paired with increasing psychological torment. He experienced auditory hallucinations—both angelic melodies that inspired compositions and tormenting sounds that drove him to despair. His wife Clara documented his deterioration in heartbreaking detail.

By 1854, neurosyphilis had advanced to its final stage. After attempting suicide by jumping into the Rhine River, he spent his final two years in an asylum. His compositions show the dual nature of his illness—both creative inspiration and eventual destruction.

7. Guy de Maupassant (1850–1893), French novelist and short-story writer

The master of the short story openly chronicled his battle with syphilis, contracted at 27. His works grew increasingly macabre as the disease progressed, reflecting his deteriorating mental state.

Maupassant’s doctor prescribed travels to sunny climates and hydrotherapy, alongside mercury—all useless against the advancing infection. Friends watched helplessly as he experienced hallucinations, seeing his own double (a symptom he transformed into the chilling story “The Horla”).

By 1892, he attempted suicide with a paperknife and was committed to an asylum. His final eighteen months were spent in near-complete dementia, the brilliant mind that created over 300 stories destroyed by syphilitic paresis at just 42.

8. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), French painter and lithographer

The bohemian artist who immortalized Parisian nightlife carried a double burden: congenital syphilis from birth and alcoholism in adulthood. His distinctive appearance—adult-sized torso with child-sized legs, reaching only 4’8″ tall—resulted from syphilis-damaged bone development.

Despite physical challenges, Toulouse-Lautrec immersed himself in Montmartre’s vibrant cabaret scene. His paintings of dancers and prostitutes were informed by intimate knowledge of their world and his own outsider status.

By his mid-30s, syphilis combined with alcoholism triggered hallucinations and paralysis. Confined to a sanitarium in 1899, he created drawings from memory to prove his sanity before dying at 36—his brilliant artistic legacy compressed into just a decade of work.

9. Al Capone (1899–1947), American gangster

The notorious Chicago crime boss contracted syphilis in his youth but refused treatment out of embarrassment. Behind his fearsome public image, Capone suffered increasingly severe symptoms while imprisoned at Alcatraz.

Prison doctors diagnosed neurosyphilis in 1938, noting his confused ramblings and deteriorating memory. Guards reported him speaking to long-dead associates and fishing with an imaginary line in his cell toilet.

Released in 1939 due to his medical condition, Capone retreated to his Florida mansion with the mental capacity of a 12-year-old. The gangster who once controlled Chicago’s underworld spent his final years playing with toy ducks in his swimming pool, his mind destroyed by a disease that could have been treated had he sought help earlier.

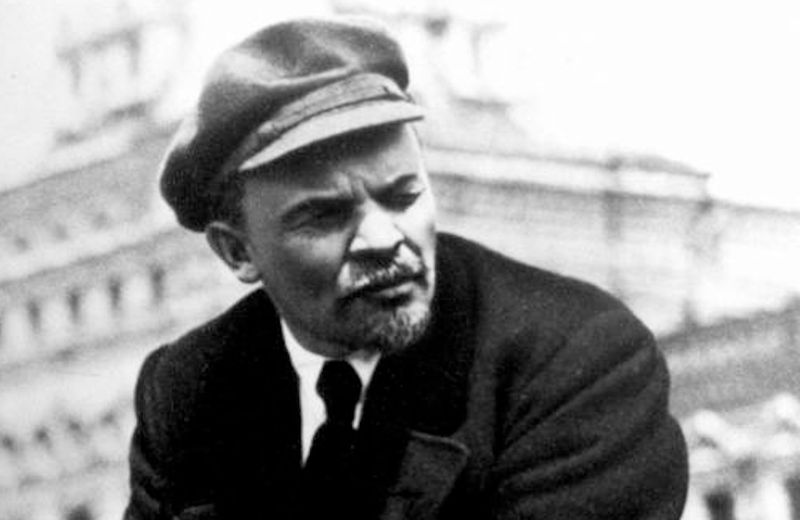

10. Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), Russian revolutionary leader

Controversial posthumous analyses suggest the Bolshevik leader suffered from neurosyphilis in his final years. Lenin experienced three debilitating strokes between 1922-1924, showing symptoms consistent with late-stage syphilis: personality changes, partial paralysis, and speech impairment.

His physicians’ records note treatments with Salvarsan and bismuth—specific anti-syphilitic medications of the era. Soviet authorities strictly controlled this medical information, considering it politically damaging.

When Lenin died at 53, officials refused autopsy requests that might confirm syphilis. His brain, preserved for study, shows damage patterns consistent with the disease. If true, the Russian Revolution’s architect may have made critical decisions while experiencing neurosyphilitic cognitive decline—potentially altering Soviet history’s trajectory.