Sports halls of fame are meant to celebrate the greatest athletes of all time. But sometimes, players get in based on popularity, memorable moments, or team success rather than true greatness. The following athletes have all been enshrined in their respective sport’s hall of fame, yet many fans and analysts question whether they truly deserve this highest honor.

1. Eli Manning: Super Bowl Hero, Regular Season Average

The Manning name carries weight in football circles, but Eli’s overall career numbers tell a conflicting story. Despite heroic performances in two Super Bowl victories against the Patriots, his regular season statistics paint the picture of mediocrity. Only four Pro Bowl selections in 16 seasons, more interceptions than many Hall of Famers, and a career completion percentage of just 60.3% raise legitimate questions. His 117-117 regular season record as a starter perfectly symbolizes his middle-of-the-road career. While clutch moments define legacies, the Hall of Fame traditionally rewards consistent excellence—something Manning’s rollercoaster career lacked outside those two magnificent playoff runs.

2. Harold Baines: Longevity Over Dominance

Baseball’s 2019 Veterans Committee selection of Harold Baines shocked even Baines himself. Despite amassing 2,866 hits across 22 seasons, Baines never finished higher than 9th in MVP voting and made just six All-Star appearances. His career lacked the signature statistical achievements that typically define Cooperstown inductees. No batting titles, no 3,000 hits, no 500 home runs. Primarily a designated hitter for much of his career, Baines provided minimal defensive value. While respected as a consistent, professional hitter, his selection lowered the traditional Hall of Fame standards. Many superior players with more impressive peaks remain outside looking in while Baines has a plaque.

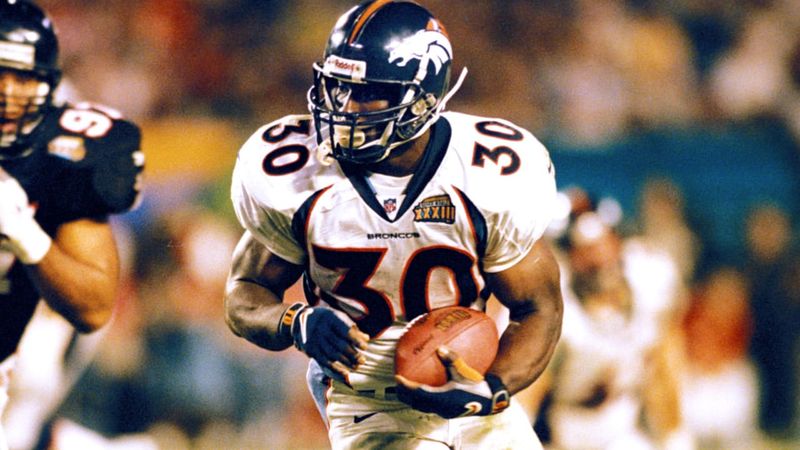

3. Terrell Davis: Brilliant But Brief

Few running backs have ever reached the heights Terrell Davis did during his 1998 MVP season. Rushing for 2,008 yards and powering the Broncos to a Super Bowl title cemented his place in NFL history. The problem? His career effectively lasted just four seasons before devastating knee injuries derailed his trajectory. While his peak was undeniable—three First-Team All-Pro selections and a Super Bowl MVP—his career totals (7,607 rushing yards) fall far below most Hall of Fame running backs. Davis represents the ongoing debate about whether a short period of absolute brilliance deserves the same recognition as sustained excellence over many years. His induction opened doors for other short-career stars.

4. Jack Morris: Clutch Pitcher, Mediocre ERA

Morris’s legendary 10-inning shutout in Game 7 of the 1991 World Series remains one of baseball’s greatest performances. Yet his career 3.90 ERA would be the highest of any starting pitcher in Cooperstown. Supporters point to his durability (175 complete games) and big-game reputation as justification. Critics note his pedestrian ERA+ of 105 (just 5% better than league average) and lack of dominating statistical seasons. Morris never won a Cy Young Award or led the league in ERA. After 15 years on the writers’ ballot without election, the Veterans Committee finally enshrined him in 2018. His case exemplifies how narrative and memorable moments sometimes outweigh consistent statistical excellence in Hall of Fame debates.

5. Tracy McGrady: Spectacular Peak, Playoff Disappointments

T-Mac’s offensive arsenal during his prime rivaled anyone in basketball history. The back-to-back scoring champion (2003-2004) could seemingly score at will, once dropping 13 points in 33 seconds to complete an improbable comeback. However, McGrady’s Hall of Fame case suffers from two significant shortcomings. His prime was abbreviated by persistent back and knee injuries that diminished him by age 30. More damaging was his playoff record—McGrady never advanced past the first round as a team’s primary star. While injuries weren’t his fault, the Basketball Hall of Fame traditionally rewards players who demonstrated both individual brilliance and team success. McGrady’s induction in 2017 prioritized his breathtaking talent over his incomplete résumé.

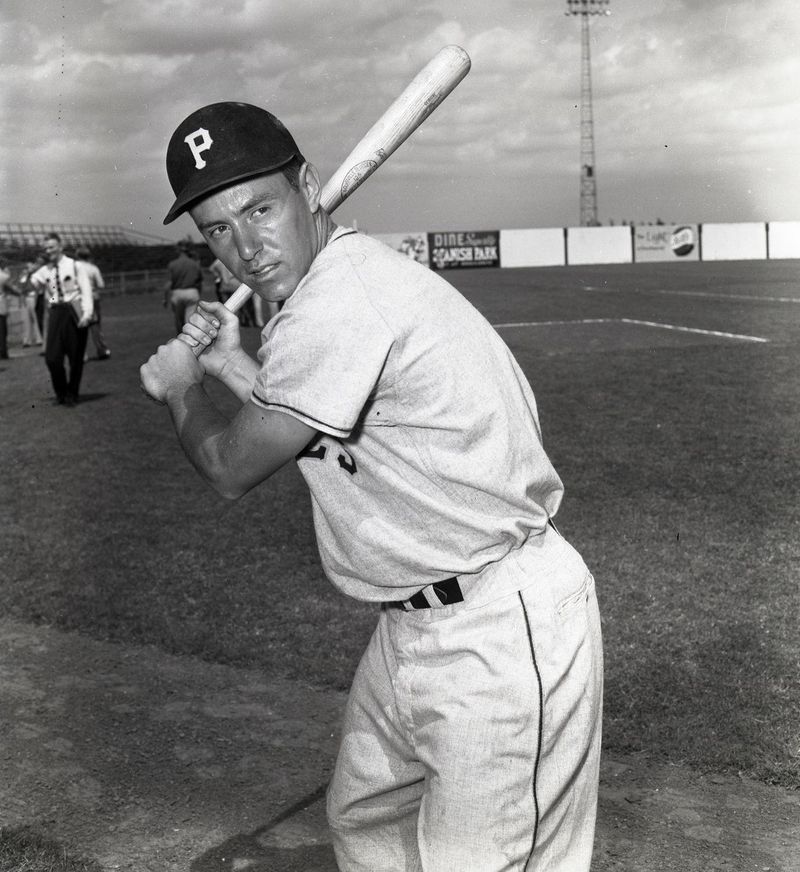

6. Bill Mazeroski: One Swing, Modest Career

October 13, 1960—the date Mazeroski hit the only Game 7 walk-off home run in World Series history. That single swing against the Yankees immortalized him in baseball lore and eventually helped secure his Cooperstown plaque in 2001. Beyond that iconic moment, Mazeroski’s offensive numbers fall dramatically short of Hall standards. A career .260 hitter with just 138 home runs and a below-average 84 OPS+, his case rests heavily on his defensive prowess at second base. While regarded as perhaps the finest fielding second baseman ever (eight Gold Gloves), the Veterans Committee’s decision to enshrine a player primarily for defense and one historic swing remains controversial. His selection represents the power of singular moments to overshadow career-long mediocrity.

7. Lynn Swann: Highlight Reel Over Consistency

Few receivers made more spectacular catches on bigger stages than Lynn Swann. His acrobatic grabs in Super Bowl X created lasting images that helped define the 1970s Steelers dynasty. The problem lies in his surprisingly modest career totals. Swann played just nine seasons, accumulating only 336 catches for 5,462 yards—numbers that many modern receivers surpass in five seasons. He never led the league in receptions or receiving yards and made just three Pro Bowls. Swann’s induction speaks to the power of memorable moments and championship success over statistical accumulation. His relatively quick enshrinement opened the door for other receivers with limited production but memorable highlights on successful teams.

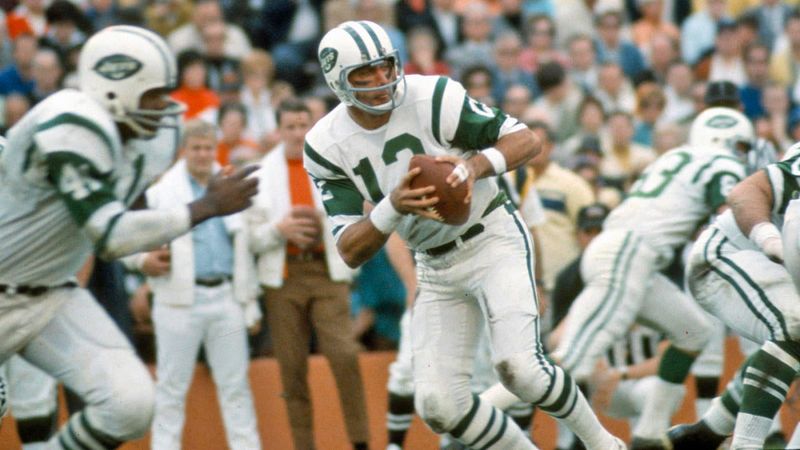

8. Joe Namath: Cultural Icon, Statistical Disappointment

Broadway Joe’s guarantee before Super Bowl III and subsequent victory over the heavily favored Colts changed football history. That singular achievement, combined with his larger-than-life personality, secured his place in Canton despite troubling career numbers. Statistically, Namath threw 173 touchdowns against 220 interceptions with a mediocre 50.1% completion rate. Only three of his 13 seasons could be considered good by objective standards, and injuries diminished his effectiveness after age 26. Namath represents perhaps the most extreme case of cultural impact and historical significance trumping statistical performance for Hall selection. His legacy as the first true football celebrity who helped legitimize the AFL-NFL merger outweighed his often subpar on-field production.

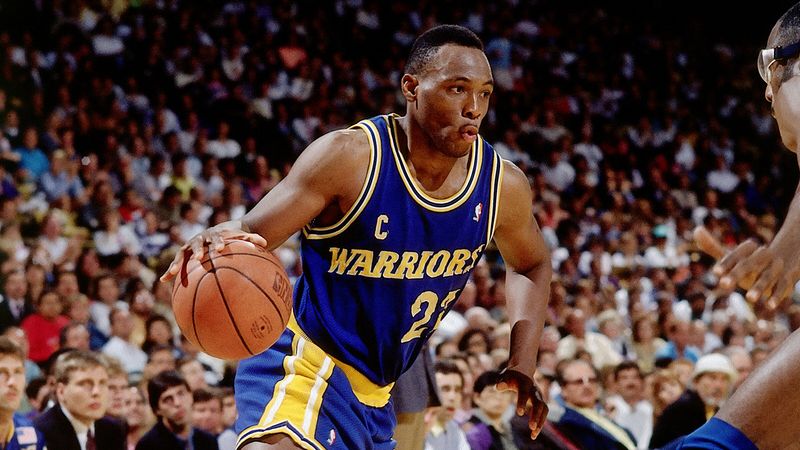

9. Mitch Richmond: Great Scorer, Forgettable Teams

Richmond’s smooth scoring touch produced six straight seasons averaging over 21 points per game. As part of Golden State’s “Run TMC” trio and later with Sacramento, he established himself as one of the premier shooting guards of the 1990s. What’s missing from Richmond’s résumé is team success and true elite status. His teams made the playoffs just twice during his prime years, winning only one series. Despite six All-Star appearances, he never made an All-NBA First Team and was rarely considered among the league’s top 10 players. Richmond’s 2014 induction exemplifies how consistent scoring over a decade can sometimes outweigh the lack of playoff success or true superstar status that typically defines Hall of Fame careers.

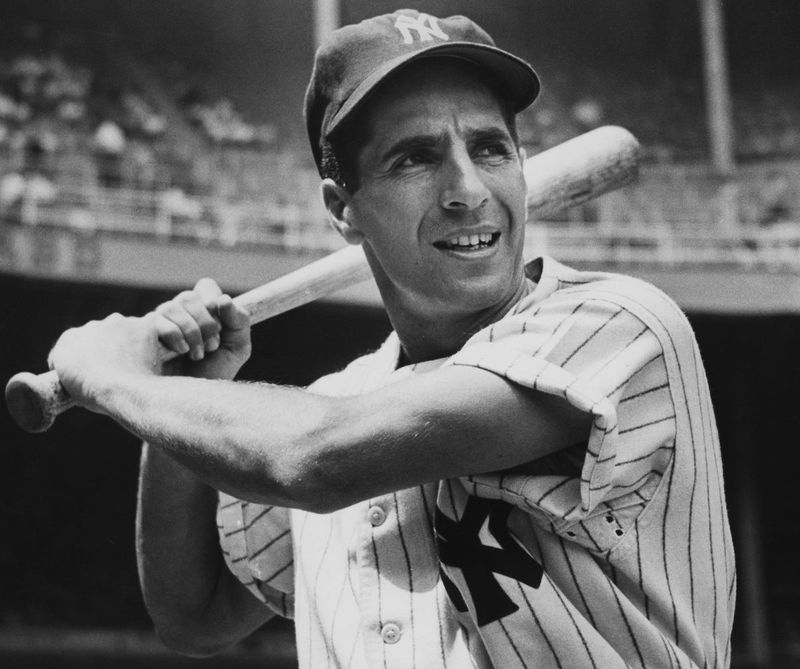

10. Phil Rizzuto: Yankees Bias in Bronze

The “Scooter” benefited enormously from playing shortstop for the Yankees during their greatest dynasty. While a solid player who contributed to seven World Series championships, his individual statistics hardly scream Cooperstown. Rizzuto’s career .273 batting average with minimal power (38 career home runs) and an OPS+ of just 93 (below league average) would never earn induction for a player on a less storied franchise. His 1950 MVP season stands as his only truly outstanding year. After failing to gain election via writers for 15 years, the Veterans Committee finally enshrined him in 1994—coincidentally after his popular broadcasting career enhanced his visibility. His selection represents the historical advantage of wearing pinstripes when borderline cases are considered.

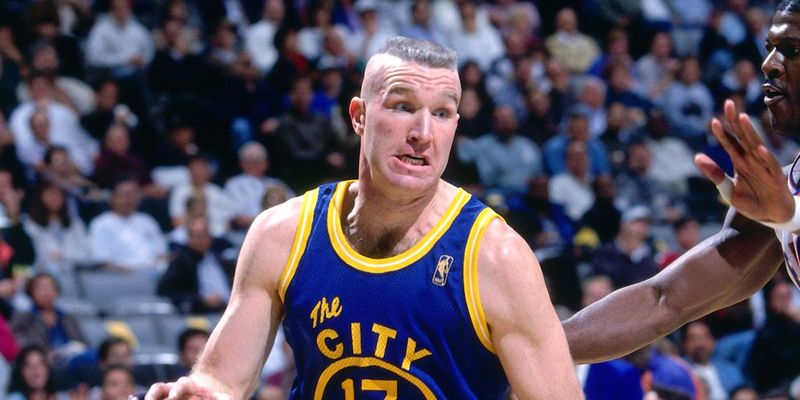

11. Chris Mullin: Golden Boy Without Golden Success

Mullin’s picture-perfect jump shot and scoring prowess made him one of the NBA’s premier offensive weapons during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The Golden State star averaged over 25 points per game for five consecutive seasons. Despite his scoring talent, Mullin’s teams achieved limited playoff success, never advancing beyond the second round during his prime years. He made five consecutive All-Star teams but was never considered among the truly elite players who defined his era. His Olympic gold medals with the 1984 amateur team and 1992 Dream Team enhanced his profile. Mullin’s 2011 induction reflects how being a very good player for a decade, rather than a transcendent one, has sometimes proven sufficient for Springfield enshrinement.

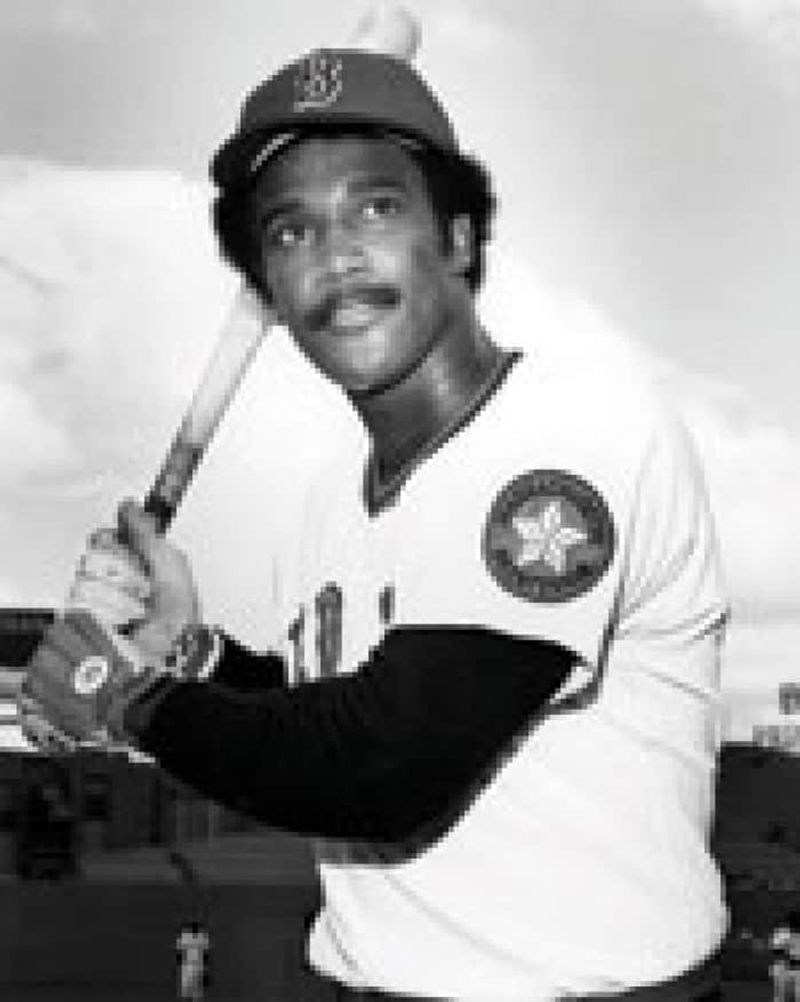

12. Jim Rice: Brief Dominance, Sharp Decline

For a seven-year stretch (1975-1981), Rice struck fear into opposing pitchers as baseball’s most intimidating slugger. The Red Sox outfielder led the American League in home runs three times during this peak, culminating in his 1978 MVP season. What hurts Rice’s case is how dramatically his performance declined after age 33. His final five seasons saw him transform from superstar to replacement-level player. Despite impressive peak numbers, his career totals (382 home runs, 2,452 hits) fall short of traditional Hall of Fame benchmarks. Rice waited 15 years before finally gaining election in his final year of eligibility, reflecting voters’ hesitation about a player whose greatness, while undeniable, lasted less than a decade.

13. Andre Reed: Solid Receiver, Never Elite

As Jim Kelly’s favorite target during Buffalo’s four consecutive Super Bowl appearances, Reed compiled impressive career numbers (951 receptions, 13,198 yards). His consistency and durability over 16 seasons helped him accumulate statistics worthy of Hall consideration. What’s missing from Reed’s résumé is any period of true dominance. Despite making seven Pro Bowls, he never earned First-Team All-Pro honors and never led the league in any major receiving category. Contemporary receivers like Michael Irvin and Sterling Sharpe were generally considered superior talents. Reed waited nine eligibility years before induction, reflecting voters’ uncertainty about a receiver who was very good for a long time but rarely considered among the NFL’s elite at his position.

14. Kevin Lowe: Edmonton’s Fortunate Son

Lowe collected six Stanley Cup rings while playing alongside Wayne Gretzky, Mark Messier, and other Edmonton Oilers legends. A steady defensive presence during hockey’s highest-scoring era, he provided reliability on a team filled with offensive superstars. The problem? Lowe was never considered among the NHL’s elite defensemen. He never won a Norris Trophy (or even received serious consideration), made just six All-Star games in 19 seasons, and provided minimal offensive production from the blue line. His 2020 induction appears to reward team success more than individual excellence. Many hockey observers believe Lowe’s selection reflects the Hockey Hall of Fame’s tendency to eventually honor most key contributors from dynasty teams regardless of their individual merits.

15. Yao Ming: Global Impact Over Career Achievement

Standing 7’6″, Yao revolutionized basketball’s global footprint by opening the crucial Chinese market to the NBA. His skill level defied traditional stereotypes about giant centers, displaying remarkable shooting touch and passing ability during his eight seasons. Injuries ultimately devastated Yao’s career potential. Chronic foot and ankle problems limited him to just 486 career games—fewer than six full seasons. His teams advanced past the first round of the playoffs only once, and he never competed for an NBA championship. Yao’s 2016 induction clearly valued his international impact and cultural significance above traditional accomplishments. His selection established that transforming the sport’s global business model could outweigh limited on-court achievements in Hall of Fame consideration.

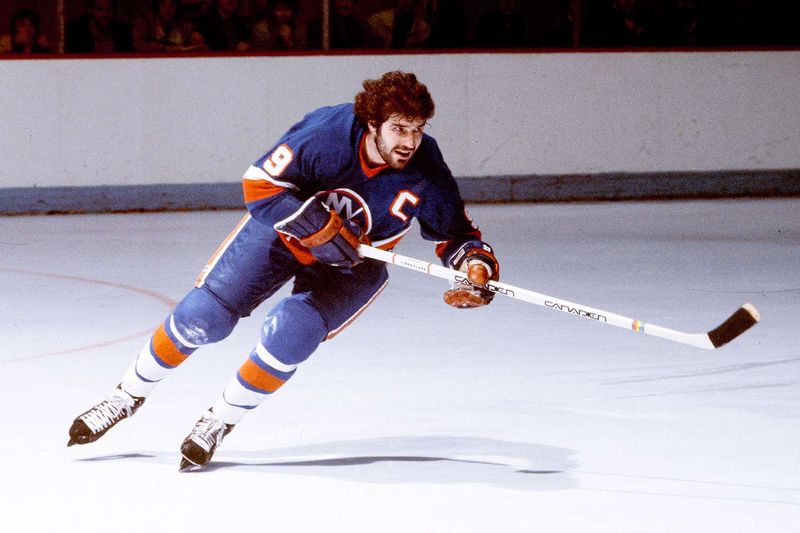

16. Clark Gillies: Dynasty Role Player

As the left wing on the New York Islanders’ top line during their early 1980s dynasty, Gillies contributed to four consecutive Stanley Cup championships. His physical presence and willingness to protect superstar teammates like Mike Bossy made him valuable beyond statistics. However, Gillies was clearly the third-most important member of his own line behind Bossy and Bryan Trottier, both undisputed all-time greats. His 697 career points in 958 games represent good but not exceptional production for a Hall of Fame forward. After initially being passed over, Gillies gained induction in 2002—nearly two decades after retirement. His selection exemplifies how being a supporting cast member on historically dominant teams can eventually lead to hockey immortality despite never being considered among the sport’s elite talents.

17. Dino Ciccarelli: Compiler Without Hardware

Ciccarelli’s 608 career goals place him among hockey’s most prolific scorers. The pesky winger tormented goalies and opponents alike during a 19-year career spent with five different franchises, showing remarkable consistency and durability. What kept Ciccarelli waiting 12 years after retirement for his Hall call was a notable lack of team success or individual accolades. He never won a Stanley Cup, never earned First-Team All-Star honors, and never captured any major NHL awards. His eventual 2010 induction represents the Hockey Hall of Fame’s tendency to ultimately recognize statistical compilers. Many hockey purists question whether impressive career totals should outweigh the absence of championships or recognition as truly elite during a player’s actual career.

18. Jerome Bettis: Volume Over Efficiency

“The Bus” steamrolled defenders for 13 seasons, finishing with 13,662 rushing yards—eighth-most in NFL history when he retired. His bruising style and likability made him a fan favorite, while his storybook ending (winning Super Bowl XL in his hometown Detroit) created the perfect narrative. The statistical case against Bettis centers on his inefficiency. His career 3.9 yards per carry ranks among the lowest for Hall of Fame running backs. After age 30, he averaged just 3.3 yards per attempt—production that continued primarily because of his team’s commitment rather than his effectiveness. Bettis represents how personality, narrative, and accumulation of counting stats can sometimes outweigh efficiency metrics in Hall of Fame voting.