The American West was shaped by the fierce resistance of the Comanche and Sioux nations against expanding U.S. forces in the 19th century. These powerful Indigenous peoples fought not just for territory, but for their very way of life as settlers pushed westward. Their military prowess, cultural resilience, and strategic thinking created conflicts that would forever change the landscape of North America.

1. Comancheria: The Forgotten Empire

Long before Texas became a state, the Comanche ruled a vast territory spanning four modern states. Their domain, known as Comancheria, stretched across present-day Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Kansas – a genuine empire by any standard.

For nearly 150 years, no European power could overcome their military might. Spanish, Mexican, Texan, and early American forces all failed to penetrate their territory.

The Comanche controlled trade routes, collected tribute from neighboring tribes, and established a complex economy centered around buffalo hunting and horse trading.

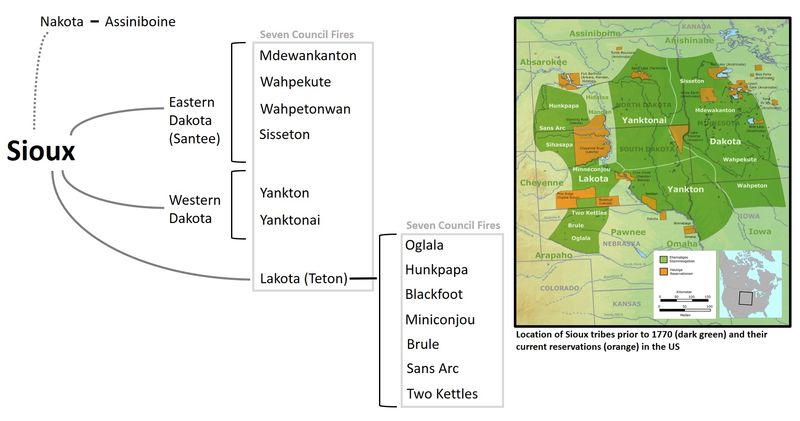

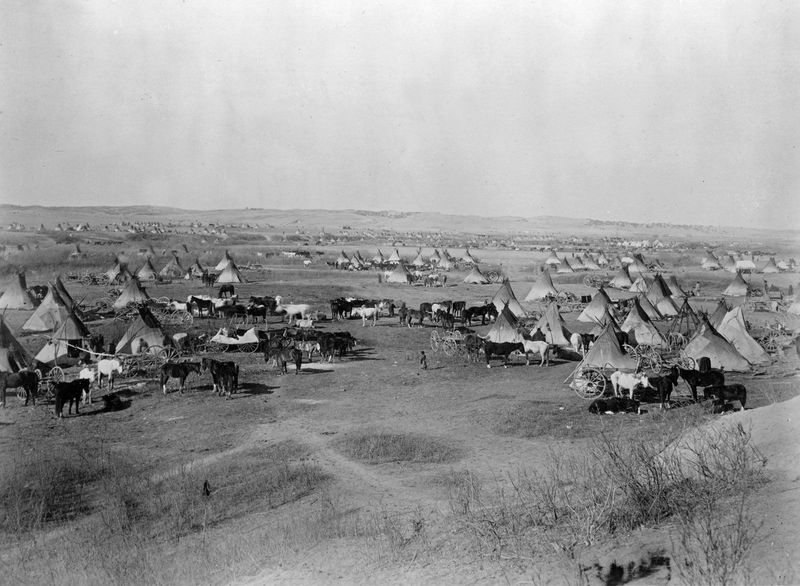

2. The Three Branches of the Great Sioux Nation

What many called simply “the Sioux” actually comprised three distinct groups with their own identities: the Dakota (Eastern), Nakota (Middle), and Lakota (Western). Each branch developed different dialects and lifeways while maintaining cultural connections.

These divisions arose naturally as the people adapted to different environments after migrating westward from Minnesota. The Lakota, who moved furthest west, became the most renowned buffalo hunters and warriors.

During conflicts with the U.S., these branches could unite into a formidable alliance, as demonstrated at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

3. Masters of Mounted Warfare

Comanche warriors transformed from pedestrian hunters into the world’s finest light cavalry within a single generation. After acquiring horses from Spanish settlements, they developed techniques allowing them to shoot arrows accurately while hanging alongside their galloping mounts.

Children began riding before they could walk, strapped to specially designed saddles. By adulthood, warriors could ride 100 miles in a day, fight effectively at full gallop, and communicate complex battle plans through hand signals.

Their horsemanship was so exceptional that the U.S. Cavalry adopted many of their techniques for its own mounted units.

4. The Military’s Most Feared Adversaries

U.S. military leaders considered the Comanche the most formidable fighters on the frontier, even more dangerous than the Apache or Sioux. Colonel Ranald Mackenzie, a seasoned Indian fighter, wrote that “no soldiers on earth could match them on horseback.”

Their tactical approach emphasized mobility, surprise, and psychological warfare. Comanche raiders could strike settlements hundreds of miles apart within days, creating an impression they were everywhere at once.

Even the Texas Rangers, formed specifically to combat Comanche raids, struggled to develop effective countermeasures against their lightning attacks.

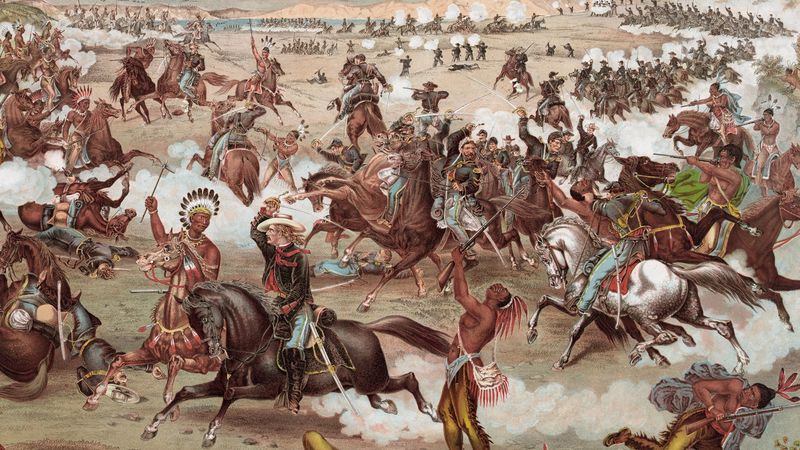

5. Victory at Little Bighorn: The Battle That Stunned America

On June 25, 1876, a coalition of Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors delivered a crushing defeat to Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his 7th Cavalry. The battle lasted just over an hour but claimed the lives of Custer and approximately 268 U.S. soldiers.

Led by war chiefs Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, the Indigenous force numbered between 1,500 and 2,500 warriors. They employed sophisticated battlefield tactics, including flanking maneuvers and coordinated charges.

The victory sent shockwaves through American society but ultimately intensified government efforts to subdue Native resistance.

6. The Feared Raiders of Northern Mexico

Comanche war parties regularly traveled hundreds of miles into Mexico, creating a zone of terror locals called “La Comanchería.” Their lightning raids struck as far south as Durango, nearly 700 miles from their homeland.

Mexican authorities were so desperate they offered bounties for Comanche scalps in the 1830s and 1840s. Towns built watchtowers specifically to spot approaching Comanche raiders, and farmers abandoned fertile lands rather than face the threat.

These raids weren’t just about plunder – they were strategic operations that secured horses, captives, and intelligence while projecting power far beyond Comanche territory.

7. Captives Who Became Family

Contrary to popular belief, both Comanche and Sioux often incorporated captives into their societies rather than simply holding them prisoner. Young captives were frequently adopted into families to replace deceased relatives, receiving the same status and privileges as biological children.

Many captives, especially those taken as children, fully assimilated and refused to return to white society when given the chance. The story of Cynthia Ann Parker, who was captured as a child and later became the mother of Quanah Parker, illustrates this cultural integration.

This practice helped maintain population numbers depleted by warfare and disease.

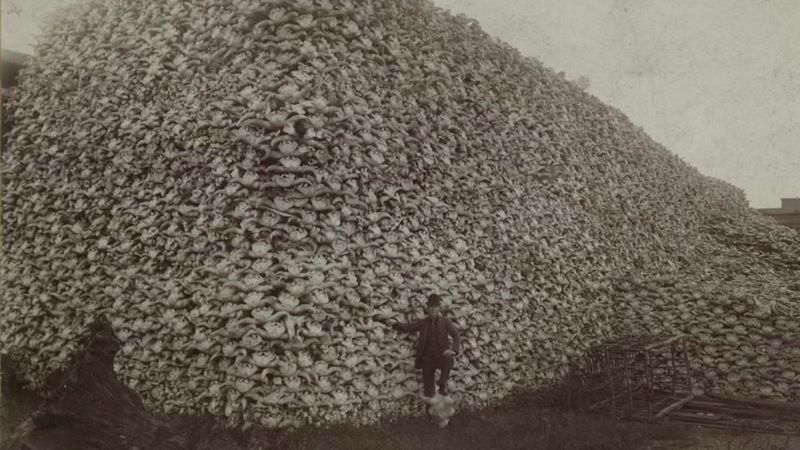

8. Buffalo Genocide as Military Strategy

American military leaders understood that destroying buffalo herds would cripple Plains tribes more effectively than direct combat. General Philip Sheridan famously declared, “Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated.”

Professional hunters using long-range rifles killed millions of buffalo, reducing the population from approximately 30 million to fewer than 1,000 by 1890. Without buffalo, the Comanche and Sioux lost their primary food source, materials for shelter and clothing, and religious connections.

This environmental warfare succeeded where military campaigns had failed, forcing starving tribes onto reservations.

9. Quanah Parker: From Warrior to Statesman

Born to a Comanche chief and a white captive, Quanah Parker embodied the collision of two worlds. As the last great Comanche war chief, he led fierce resistance against U.S. forces throughout the 1860s and early 1870s.

After surrender, he made an extraordinary transition to reservation life, adopting aspects of white culture while preserving Comanche traditions. He established a successful cattle ranch, advocated for Native rights in Washington, and helped found the Native American Church.

His diplomatic skills allowed him to maintain Comanche dignity during a period of profound cultural upheaval.

10. Crazy Horse: The Unconquerable Spirit

Lakota warrior Crazy Horse remains perhaps the most enigmatic figure from the Sioux Wars. Known for his battlefield genius, he never allowed himself to be photographed, believing cameras would steal his spirit.

His vision quests and spiritual practices gave him a mystical reputation among both Natives and whites. Fellow warriors claimed he wore a small stone behind his ear and painted himself with hailstones for protection in battle.

After surrendering in 1877, he was killed under suspicious circumstances while in custody at Fort Robinson, Nebraska – many believe he was bayoneted while resisting imprisonment.

11. The Broken Treaty Trail

The U.S. government signed at least 368 treaties with Native nations, including numerous agreements with the Comanche and Sioux. Nearly every one was violated, often within months of signing.

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty guaranteed the Black Hills to the Sioux “for as long as the grass shall grow.” Yet when gold was discovered there in 1874, the government immediately reneged, triggering the Great Sioux War.

Similar patterns unfolded with Comanche treaties, creating deep distrust that persists to this day. The Supreme Court later acknowledged these violations, awarding the Sioux compensation they still refuse to accept.

12. Four Decades of Relentless Warfare

The Comanche Wars weren’t a single conflict but a series of battles, raids, and campaigns spanning from the 1830s to 1875. This 40-year struggle represented the longest continuous conflict between Native Americans and the United States.

During this period, the Texas frontier actually receded as settlers abandoned homesteads due to Comanche pressure. Several times, U.S. authorities believed they had secured peace, only to see hostilities erupt again when treaties were broken.

The conflict finally ended not through military victory but through the collapse of the buffalo economy and devastating epidemics.

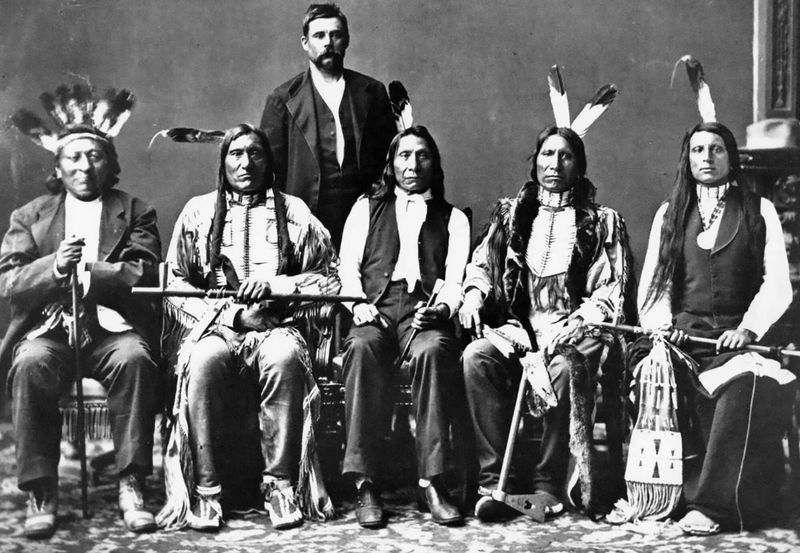

13. Red Cloud’s Triumph: The Only War Native Americans Won

Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud achieved what no other Native American leader could: he forced the U.S. government to abandon its forts and withdraw from contested territory. Between 1866 and 1868, his warriors effectively closed the Bozeman Trail by attacking every wagon train and military patrol that entered the region.

His strategic blockade of forts isolated U.S. garrisons from supplies and reinforcements. The military situation became so untenable that the government agreed to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, acknowledging Sioux control of the Powder River country.

This remains the only war the United States ever lost to Native Americans.

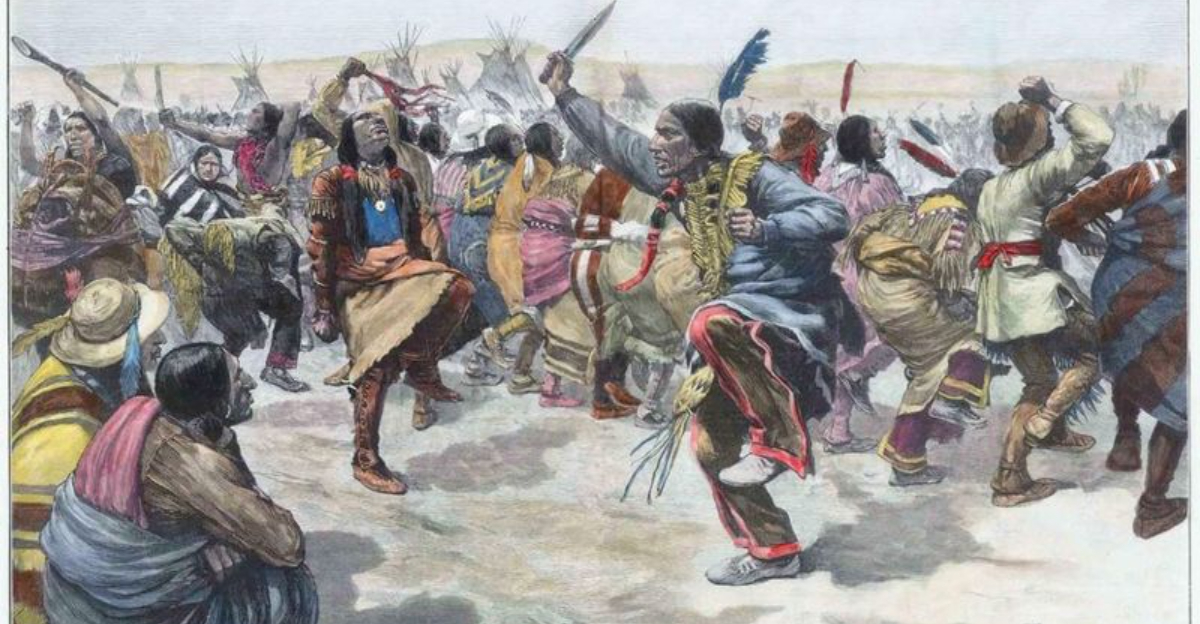

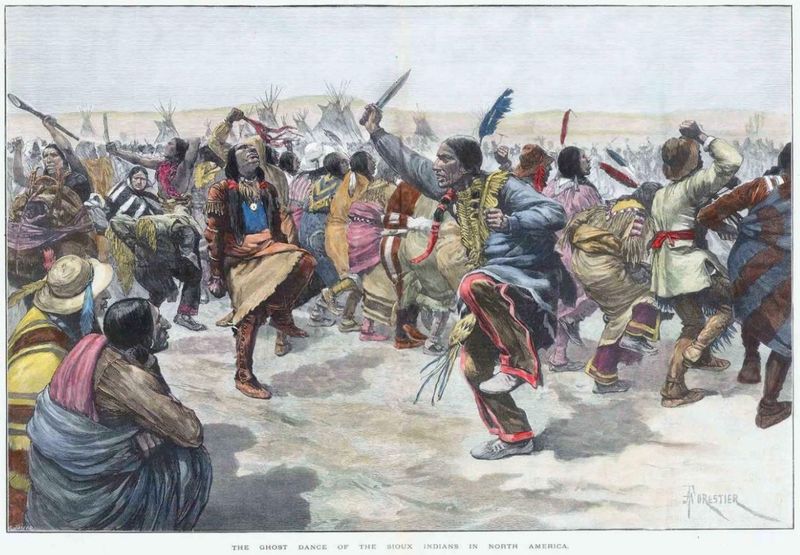

14. The Ghost Dance: Hope Before Tragedy

As traditional ways of life collapsed in the late 1880s, the Ghost Dance movement spread rapidly among the Sioux. This spiritual revival promised that performing sacred dances would reunite tribes with their ancestors, make them invulnerable to bullets, and cause white settlers to disappear.

Wovoka, a Paiute spiritual leader, founded the movement after experiencing visions during a solar eclipse. Sioux leaders like Sitting Bull embraced the practice, alarming U.S. authorities who feared it presaged rebellion.

This fear led directly to Sitting Bull’s arrest and killing, followed by the massacre at Wounded Knee where approximately 300 Sioux were killed.

15. Starvation as a Weapon of Conquest

When military campaigns proved ineffective against mobile Plains tribes, the U.S. government adopted a deliberate policy of resource destruction. Army columns targeted food supplies, burning winter stores, destroying crops, and killing horses.

On reservations, officials withheld promised food rations to force compliance with government demands. The infamous statement “Indians will be fed when they are hungry” reflected this coercive approach.

By 1879, once-proud Comanche warriors were reduced to eating their horses to survive. Similar conditions affected Sioux reservations, where malnutrition and related diseases caused thousands of deaths.

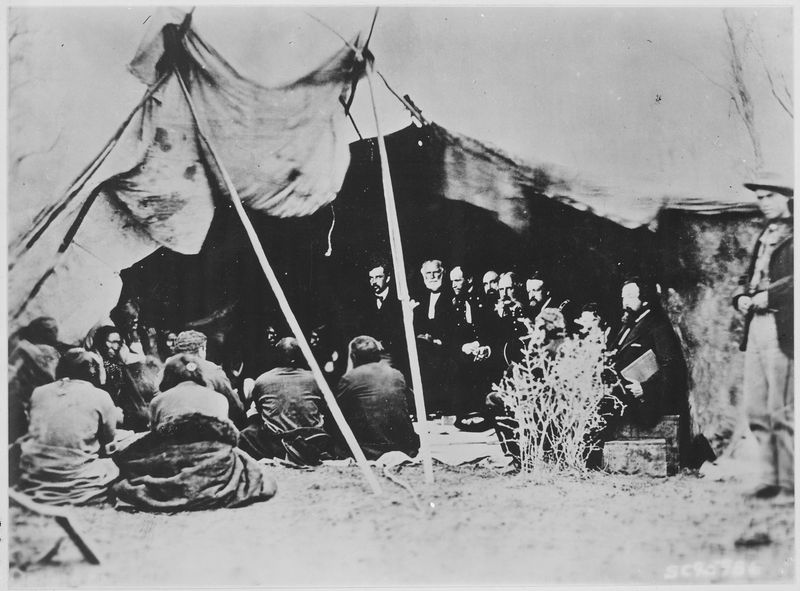

16. Warriors at the White House

Despite their fierce reputations, many Comanche and Sioux leaders were skilled diplomats who traveled to Washington to negotiate directly with American presidents. Sioux chief Red Cloud addressed Congress in 1870, eloquently defending his people’s rights in a speech that was widely reported in newspapers.

Comanche chief Ten Bears journeyed to the White House in 1863, where he told President Lincoln: “I have heard that you have a big house where you keep your children. I want to see it.”

These diplomatic missions revealed the complex political understanding tribal leaders possessed, contradicting stereotypes of them as simple “savages.”

17. Modern Resistance: The Fight Continues

The spirit of Comanche and Sioux resistance didn’t end with the 19th century wars. Today’s descendants continue fighting for sovereignty, cultural preservation, and environmental protection using legal and political means.

The Sioux-led resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock in 2016-2017 drew worldwide attention and echoed historical struggles. Comanche Nation has fought to protect sacred sites from development, winning important legal victories establishing tribal consultation rights.

Language revitalization programs, cultural centers, and educational initiatives work to reverse centuries of forced assimilation, keeping warrior traditions alive in new forms.