George Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation was home to hundreds of enslaved people who lived and worked under brutal conditions. Their stories reveal the harsh realities of slavery at the estate of America’s first president. These firsthand accounts and historical records provide a glimpse into the daily struggles, resistance, and humanity of those who were denied their freedom at this iconic American landmark.

1. Washington Inherited Enslaved People at Age 11

Young George Washington became a slave owner before he was even a teenager. His father’s death in 1743 thrust him into the role of slave master, inheriting ten human beings as property.

This early exposure to slave ownership shaped his complicated relationship with slavery throughout his life. As his landholdings expanded, so did his ownership of enslaved people, eventually totaling 123 individuals he personally owned.

The marriage to Martha brought another 153 “dower slaves” to Mount Vernon, creating a massive enslaved workforce that maintained the plantation’s prosperity while enduring lives of forced labor.

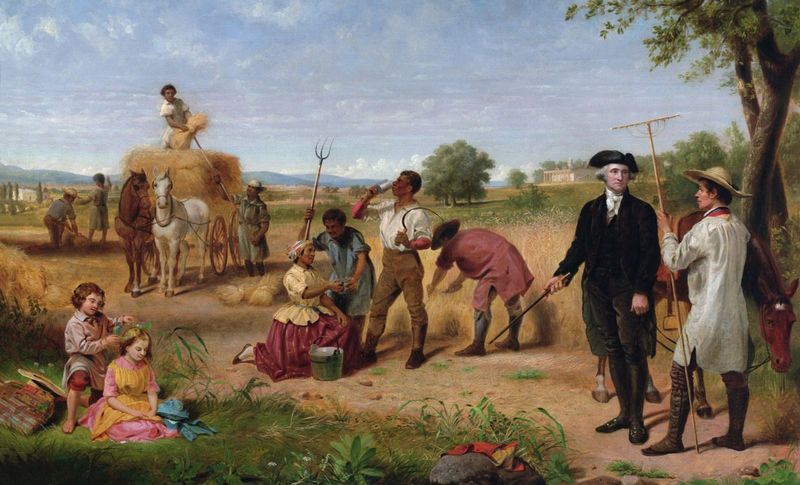

2. Six-Day Work Weeks with Sunup to Sundown Labor

From the first light of dawn until darkness fell, Mount Vernon’s enslaved population endured backbreaking labor six days each week. Field hands toiled through scorching summers and bitter winters, planting, harvesting, and maintaining Washington’s five farms.

Only the sabbath offered brief respite from constant work. Even then, many still performed essential tasks like cooking, cleaning, and tending livestock.

Washington’s detailed farm reports reveal his exacting standards and expectation of maximum productivity from dawn to dusk. The exhausting schedule left little time for family life or personal pursuits among the enslaved community.

3. Harsh Punishments for Resistance

Resistance at Mount Vernon carried severe consequences. Washington authorized overseers to use physical violence to maintain control, with whippings being a common punishment for those who defied his authority.

The carpenter Ben’s story illustrates this brutality. After attempting to escape in 1793, Washington ordered him whipped as punishment and example to others. Records show Washington occasionally sold rebellious enslaved people to the Caribbean as an especially feared punishment, separating them permanently from family.

These harsh measures created an atmosphere of fear designed to discourage rebellion and maintain the plantation’s profitability through forced compliance.

4. Skilled Labor Was Exploited for Profit

Mount Vernon depended on the expertise of its enslaved craftspeople. Talented blacksmiths forged essential tools and architectural elements, while skilled carpenters constructed buildings and furniture that still stand today.

Women weavers created textiles for clothing and household use. The plantation’s profitable gristmill operated entirely through enslaved labor, producing flour sold throughout the colonies and abroad.

Despite creating substantial wealth for Washington through their specialized skills, these artisans received no compensation for their labor. Their expertise, often learned through years of forced apprenticeship, benefited only their owner while they remained in bondage.

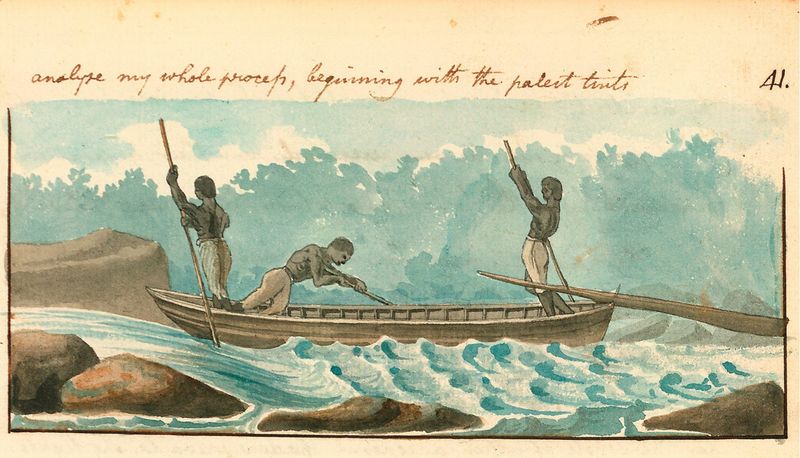

5. The Dangerous Work of Fishing

Along the Potomac’s treacherous waters, enslaved fishermen risked their lives daily. Spring shad runs meant working through freezing nights in dangerous currents, hauling massive nets weighing hundreds of pounds when full.

Frostbite claimed fingers and toes during winter fishing expeditions. Drownings occurred regularly as men struggled with heavy equipment in unpredictable waters.

Washington’s records show these fishermen harvested over a million herring annually, providing protein for the enslaved population and profitable exports. Despite the dangers and skill required, these men received no additional compensation or recognition for their perilous work that significantly contributed to Mount Vernon’s economic success.

6. Children Were Forced to Work Young

Childhood ended abruptly for enslaved children at Mount Vernon. By age 11 or 12, boys were sent to the fields alongside adults, expected to perform the same backbreaking labor despite their small stature.

Girls were typically assigned to spinning houses or domestic work, learning skills they would use their entire lives in service to the Washington household. Some children started even younger, assigned as “child minders” watching infants while their mothers worked.

Education was nonexistent for these young laborers. Instead of learning to read or write, they received only the training necessary to maximize their value as lifelong workers on the plantation.

7. Poor Living Conditions

Home for most enslaved people at Mount Vernon meant cramped, drafty wooden cabins. Multiple families often shared a single room with dirt floors and minimal privacy.

Archaeological excavations reveal these dwellings lacked proper insulation against Virginia’s harsh winters and sweltering summers. Furniture was sparse—typically just pallets for sleeping and perhaps a table fashioned from discarded materials.

Smoke from cooking fires filled the interiors, as proper chimneys were rare luxuries. Despite these conditions, enslaved families transformed these spaces into homes, creating community and maintaining cultural traditions within the confines of their meager shelters.

8. Malnutrition and Hunger

Hunger was a constant companion for Mount Vernon’s enslaved community. Washington’s ledgers show weekly rations—typically cornmeal, salt herring, and occasional small portions of meat—were barely sufficient for survival, especially considering the physical demands of plantation labor.

Enslaved people developed creative survival strategies to supplement these meager provisions. Small garden plots behind cabins yielded vegetables, while some hunted possums and raccoons after exhausting workdays.

Fishing in streams and gathering wild plants provided additional nutrition. This persistent food insecurity contributed to higher rates of illness and shorter lifespans among the enslaved population compared to their white counterparts.

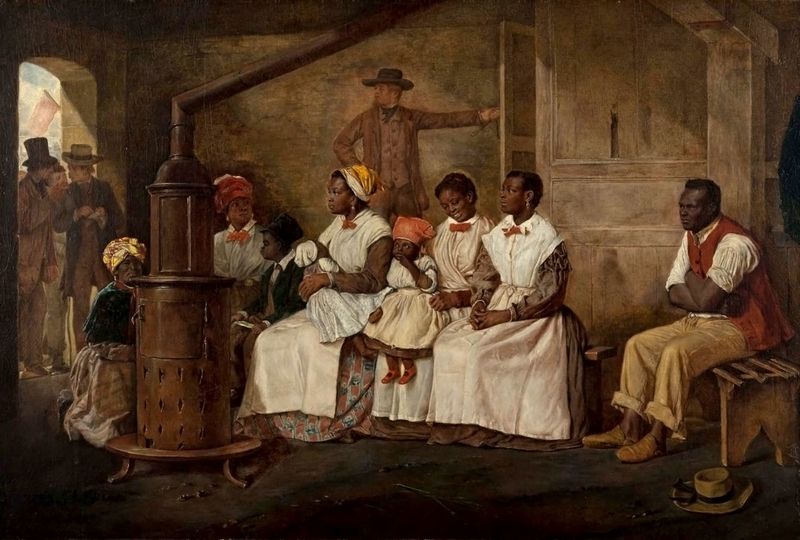

9. Family Separation Was a Constant Fear

The threat of family dissolution haunted every enslaved person at Mount Vernon. Washington’s business decisions regularly tore apart families—selling individuals to settle debts or separating children from parents through inheritance arrangements.

His presidency created additional family trauma. When serving in Philadelphia, Washington deliberately rotated enslaved servants back to Virginia before they could qualify for Pennsylvania’s gradual emancipation law.

Letters and accounts reveal the emotional devastation these separations caused. Parents watched helplessly as children were sold away, and spouses were forced apart with no legal recognition of their marriages, creating wounds that could never heal despite the community’s efforts to maintain family bonds.

10. Martha Washington Owned Enslaved People Separately

The majority of Mount Vernon’s enslaved population actually belonged to Martha Washington, not George. These 153 “dower slaves” came through her first marriage to Daniel Parke Custis and legally remained Custis family property.

This legal distinction created a cruel reality: even if George wished to free these individuals, he lacked the legal authority to do so. Their fates were tied to Martha’s descendants, regardless of the Washingtons’ personal views on slavery.

After George’s death, these dower slaves faced continued bondage while witnessing the eventual freedom of those George personally owned, creating painful divisions within the enslaved community.

11. Some Escaped—But Few Succeeded

Freedom beckoned powerfully enough for some enslaved people to risk everything. Ona Judge, Martha’s skilled personal maid, seized her opportunity in 1796 while the Washingtons dined, fleeing to New Hampshire where she evaded multiple recapture attempts.

Hercules Posey, Washington’s celebrated chef, similarly disappeared in 1797, vanishing into Philadelphia’s free Black community. His culinary talents had made him famous throughout the young nation.

These successful escapes were exceptional. Most who attempted flight were recaptured, facing harsh punishment and increased restrictions. Washington spent considerable resources advertising for runaways and hiring slave catchers to return his human property.

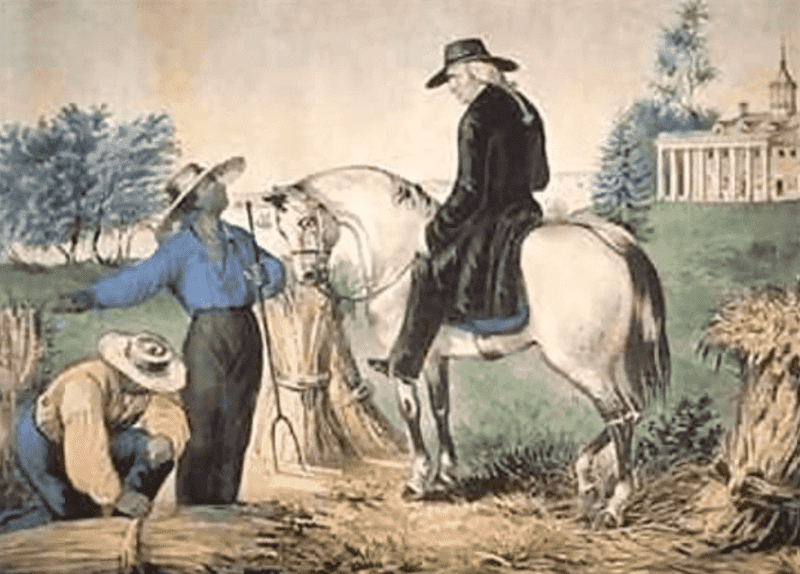

12. Washington Privately Opposed Slavery (But Did Little to End It)

Washington’s personal writings reveal his growing moral discomfort with slavery. In private letters, he described the institution as “repugnant” and contrary to American ideals of liberty.

Yet this philosophical opposition rarely translated to action during his lifetime. He continued acquiring enslaved people while president and enforced fugitive slave laws, even as he privately contemplated gradual emancipation schemes.

His final will did order freedom for his personal slaves—but only after Martha’s death, potentially decades later. This delayed emancipation plan revealed both his evolving views and his unwillingness to make personal economic sacrifices to end an institution he privately condemned.

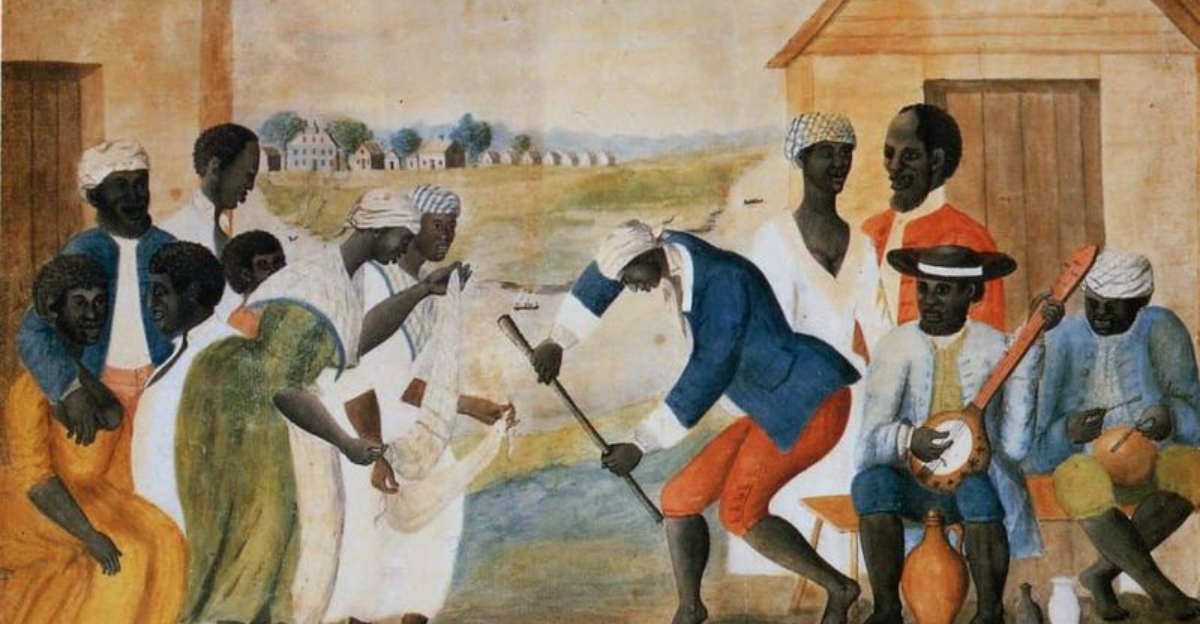

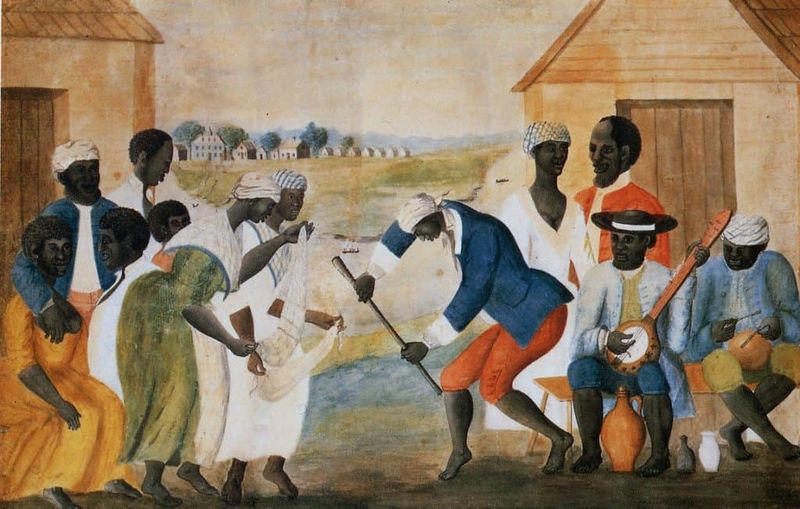

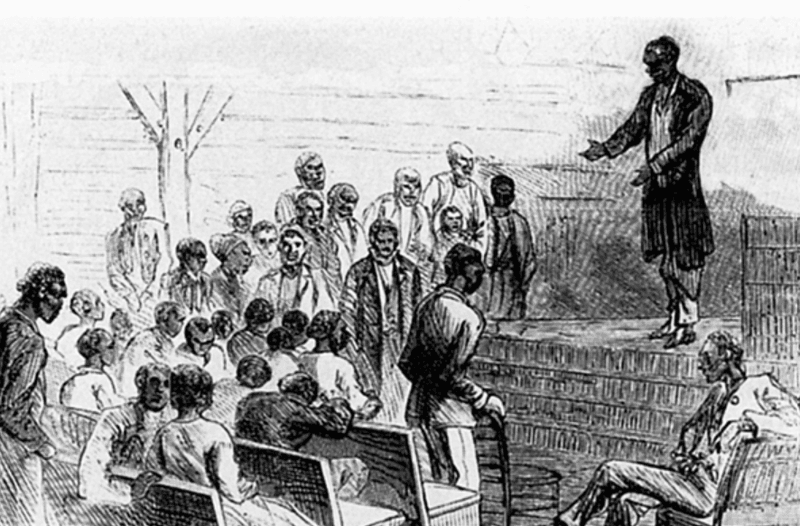

13. Enslaved People Resisted in Subtle Ways

Resistance took many forms beyond escape attempts. Enslaved workers at Mount Vernon developed sophisticated strategies to assert humanity and regain small measures of control over their lives.

Work slowdowns appeared as illness or tool breakage in Washington’s records. Careful sabotage of equipment created necessary breaks without arousing suspicion of deliberate defiance.

Religious gatherings in secret locations allowed cultural preservation and spiritual renewal away from white oversight. These acts of everyday resistance created spaces of dignity and autonomy within an oppressive system, demonstrating remarkable resilience in the face of constant dehumanization.

14. Burial in Unmarked Graves

Even in death, inequality persisted at Mount Vernon. While the Washington family rests in marked tombs visited by thousands annually, hundreds of enslaved individuals lie in unmarked graves near the plantation.

Archaeological work has identified this burial ground, where generations were laid to rest without permanent markers or recognition. Traditional African burial practices likely continued secretly here, with personal items accompanying the deceased despite official prohibitions.

This cemetery remained officially unacknowledged until 1929, nearly 130 years after Washington’s death. Today, a modest memorial stands at the site, finally providing some recognition to those whose forced labor built and maintained the estate.

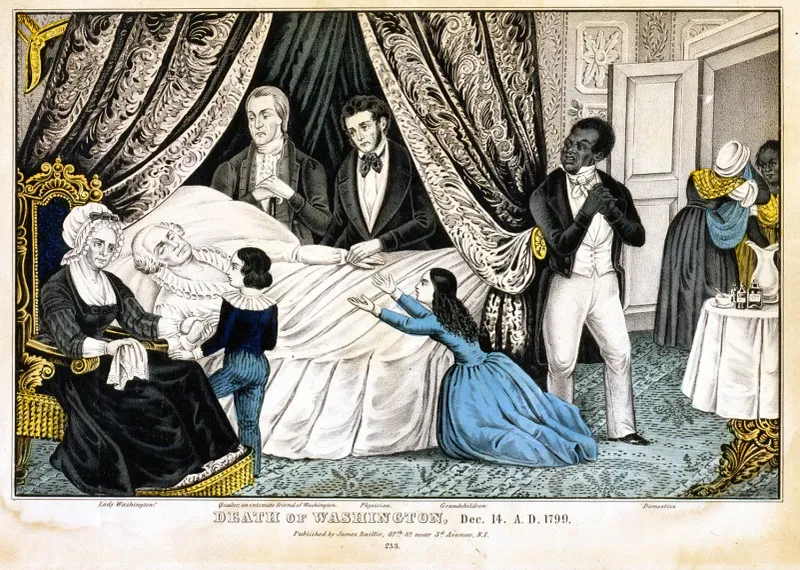

15. Washington’s Will Freed Some—But Not All

Washington’s final act regarding slavery came through his will, drafted shortly before his death in 1799. The document included unprecedented instructions to free the 123 enslaved people he personally owned once Martha died.

This provision made him the only founding father to free his enslaved workers. However, this partial emancipation excluded the majority of Mount Vernon’s enslaved community.

The 153 dower slaves belonging to Martha’s estate remained in bondage, as Washington lacked legal authority to free them. This created a divided community where some would eventually gain freedom while others faced continued enslavement under new masters.

16. Many Were Sold After Washington’s Death

After George’s death, Mount Vernon’s enslaved community faced more upheaval. Martha, fearing those scheduled for eventual freedom might hasten her death, took the unusual step of freeing Washington’s slaves early in 1801.

This rare act of emancipation affected only the 123 people George personally owned. For Martha’s dower slaves—the majority of Mount Vernon’s enslaved population—a different fate awaited.

Upon her death in 1802, these individuals were divided among her grandchildren as inheritance. Families were separated as people were distributed to different Custis heirs, continuing the cycle of bondage for generations despite Washington’s limited emancipation gesture.