Explore the fascinating evolution of Sigmund Freud’s views on religion throughout his career. This exploration offers insight into how Freud’s ideas were shaped by his experiences and the changing scientific landscape of his time, leading to a complex and often controversial understanding of religion.

1. Early Skepticism (1890s–1900s)

In the late 19th century, Freud viewed religion as a psychological crutch. He likened religious belief to obsessive rituals, and his secular Jewish upbringing influenced this perspective. Scientific materialism also played a role, encouraging Freud to see religion as wish fulfillment akin to childhood fantasies.

For Freud, religion was a manifestation of neurosis, a way to deal with existential uncertainties. This skepticism marked the beginnings of a lifelong critique. His early writings reflect a blend of curiosity and doubt, marking the initial phase of Freud’s complex relationship with religious thought.

2. Totem and Taboo (1913)

Freud’s work ‘Totem and Taboo’ delved into the origins of religion through a psychoanalytic lens. He suggested that religious practices emerged from ancient guilt over the murder of a dominant father figure by a “primal horde.”

This theory posited that early humans developed totemism as a form of collective neurotic expression. Freud drew parallels between individual neurotic behaviors and societal religious rituals, offering a provocative view on religion’s anthropological roots.

This work underscores Freud’s attempt to bridge psychology with anthropology, introducing a radical narrative on religion’s beginnings.

3. The Future of an Illusion (1927)

In ‘The Future of an Illusion,’ Freud presented religion as a collective delusion. He argued that religious belief was a projection of childhood helplessness onto a protective father figure, a theme consistent throughout his work.

Freud believed that science and reason would eventually replace religious belief, a hopeful yet controversial proposition. This work is one of Freud’s most famous critiques, encapsulating his view of religion as a comforting illusion for the masses.

Freud’s bold assertions in this book reflected his confidence in psychoanalysis as a tool to understand human culture.

4. Civilization and Its Discontents (1930)

Though critical of religion, Freud acknowledged its societal role in ‘Civilization and Its Discontents.’ He suggested that religion helped maintain social order by controlling human instincts, though at the cost of individual repression.

Freud compared religious morality to the harsh demands of the superego, capturing the double-edged nature of religious influence. This nuanced view marked a shift from his earlier rigid critiques, recognizing religion’s role as both social glue and restrictive force.

Freud’s contemplation of religion’s function in society added depth to his critique, suggesting a complex interplay between belief and behavior.

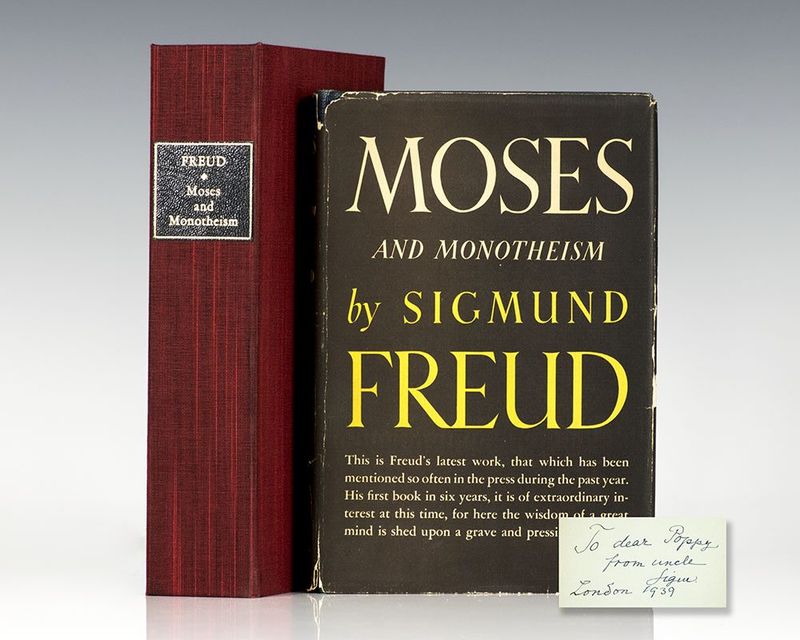

5. Moses and Monotheism (1939)

In ‘Moses and Monotheism,’ Freud tackled the origins of Judaism with a controversial thesis. He argued that Moses was an Egyptian, and monotheism arose from repressed guilt over his murder by the Jews.

This theory paralleled his primal horde concept, suggesting cultural trauma as a catalyst for religious evolution. Freud’s exploration of Judaism reflected his lifelong fascination with his heritage, despite his atheistic stance.

The work encapsulates Freud’s boldness in exploring the intersections of religion, culture, and psychology, providing a fitting capstone to his career-long inquiry into the nature of belief.