Juneteenth and the Civil Rights Movement represent two critical chapters in America’s long journey toward equality. While separated by nearly a century, these historical moments share deep connections in the ongoing fight for Black freedom and dignity. Both stories reveal how freedom on paper doesn’t always mean freedom in practice, and how generations of Americans have worked to bridge that gap.

1. The Delayed Freedom Announcement

Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865, announcing freedom to enslaved people a full two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation. This delay wasn’t accidental—Texas slaveholders deliberately withheld the news to maintain their free labor force.

Many enslaved people had no idea they were legally free. Some plantation owners waited until after harvest season to share the news, extracting one final season of unpaid work.

The day became known as ‘Juneteenth,’ combining June and nineteenth, marking when the last enslaved Americans learned of their freedom—not when they actually received it.

2. Freedom’s Legal Completion

Even after Juneteenth, slavery persisted legally in Kentucky and Delaware until December 6, 1865. These border states weren’t covered by the Emancipation Proclamation, which only applied to Confederate states.

Freedom came officially with the 13th Amendment’s ratification, which abolished slavery nationwide—with one critical exception. The amendment included the clause ‘except as punishment for crime,’ creating a loophole.

This exception fueled convict leasing systems throughout the South, where Black Americans were arrested on minor charges and forced into labor that resembled slavery. This legal loophole connected Juneteenth directly to later civil rights battles.

3. The Birth of a Cultural Celebration

Former slaves transformed their freedom day into joyful community gatherings beginning in 1866. Early celebrations featured barbecues, prayer services, and the wearing of new clothes to symbolize newfound freedom and dignity.

Juneteenth celebrations declined during the Great Depression and World War II as economic hardship and migration disrupted communities. Yet families kept traditions alive through food, stories, and small gatherings.

By the 1950s, these celebrations had evolved into powerful expressions of cultural pride and resistance. Red foods like strawberry soda became symbolic fixtures, representing the bloodshed and sacrifice of ancestors who didn’t live to see freedom.

4. Connecting Past to Present Struggles

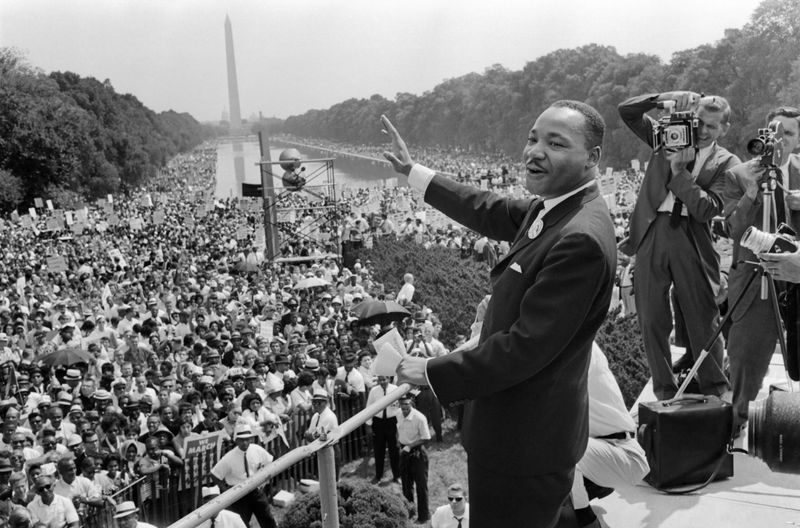

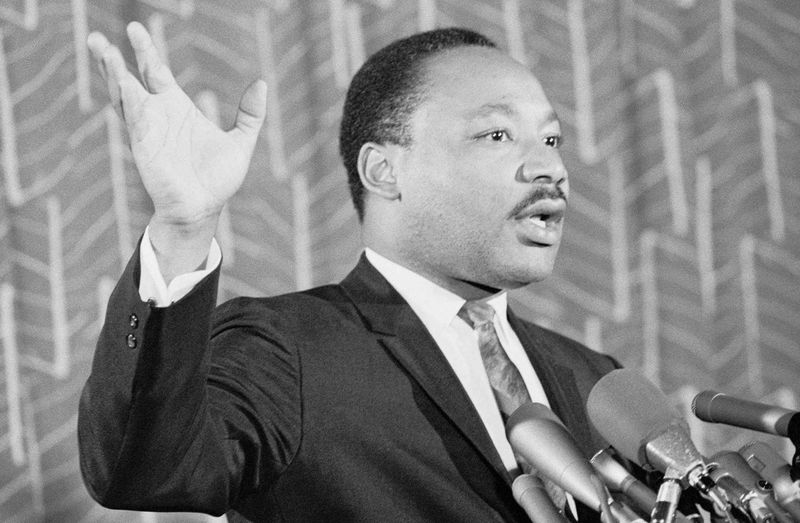

Martin Luther King Jr. deliberately framed civil rights demands within the context of slavery’s broken promises. His ‘I Have a Dream’ speech referenced the Emancipation Proclamation directly, calling it a ‘promissory note’ America had failed to honor.

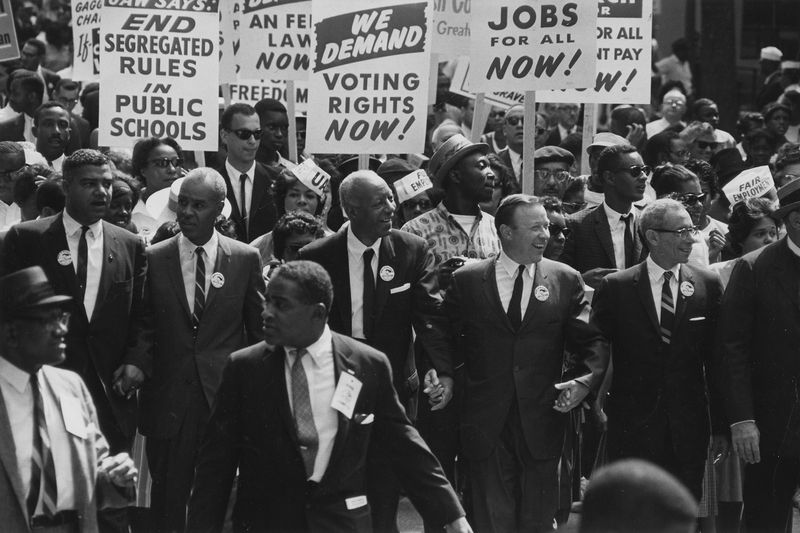

Civil rights activists strategically used historical anniversaries for major events. The March on Washington was planned for the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, drawing a clear line from 1863 to 1963.

Freedom songs during the movement often contained lyrics about breaking chains and ending bondage—metaphors connecting contemporary struggles to slavery. This historical framing helped Americans understand civil rights not as new demands, but as long-overdue fulfillment of freedom’s promise.

5. The Unfinished Work of Emancipation

Freedom without resources left many formerly enslaved people vulnerable to exploitation. The promised ’40 acres and a mule’ never materialized for most, forcing many into sharecropping arrangements that created new forms of economic bondage.

Voting rights guaranteed by the 15th Amendment were systematically stripped away through poll taxes, literacy tests, and violent intimidation. By 1900, less than 3% of eligible Black voters in some Southern states could actually cast ballots.

Civil rights activists a century later fought for these same fundamental rights—economic opportunity, voting access, and equal protection. Their struggles weren’t new demands but attempts to secure what should have followed emancipation.

6. Cultural Resistance Through Celebration

Celebrating Juneteenth was itself an act of defiance during the Jim Crow era. White authorities often discouraged or prohibited these gatherings, fearing their potential for community organizing and collective memory-keeping.

Families passed down Juneteenth traditions through generations, preserving history that was deliberately excluded from school textbooks. Elders told emancipation stories that contradicted sanitized versions of history taught in segregated schools.

Community-based Juneteenth celebrations maintained cultural continuity when official institutions tried to erase Black history. This preservation of memory created a foundation of historical consciousness that later fueled civil rights activism, showing how celebration itself can be a form of resistance.

7. How Migration Spread Freedom Traditions

Between 1916 and 1970, six million Black Americans left the South during the Great Migration. Families carried Juneteenth traditions to cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Oakland, establishing new celebrations in communities far from Texas.

Regional variations emerged as Juneteenth spread northward. Chicago’s celebrations incorporated elements of Southern, Midwestern, and urban culture, creating distinctive traditions that reflected new geographic realities.

These transplanted celebrations became community anchors for displaced families. In unfamiliar and often hostile northern cities, Juneteenth gatherings provided connection to roots and history while building solidarity among newcomers facing discrimination in their new homes.

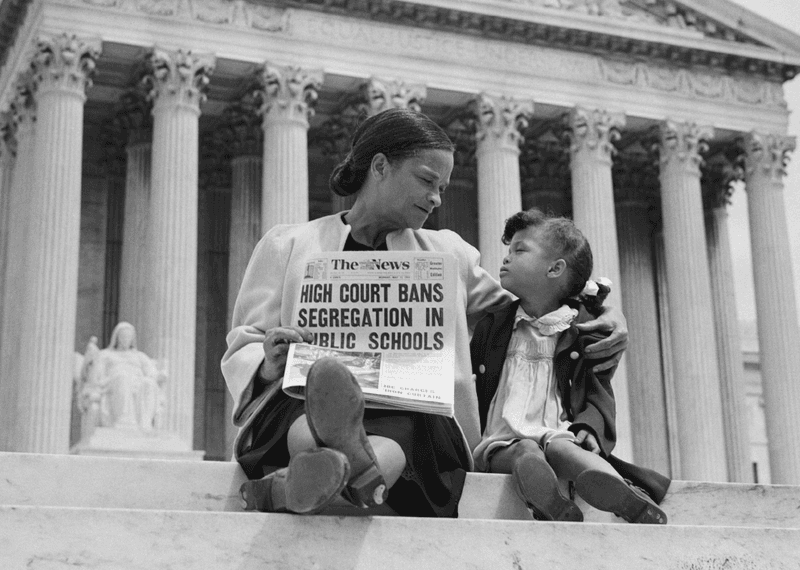

8. Legal Progress vs. Lived Reality

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination. Yet like the Emancipation Proclamation before it, the law on paper didn’t immediately translate to freedom in practice.

Southern states developed creative workarounds to maintain segregation despite federal law. Private clubs replaced public facilities, and economic pressure was applied to Black citizens who attempted to exercise their new rights.

Activists recognized that legislation alone couldn’t transform hearts and systems. The ongoing work required community organizing, economic strategies, and cultural shifts—a realization that connected them directly to the post-Juneteenth generation who had similarly discovered that legal freedom was just the beginning of true liberation.

9. The Symbolic Language of Liberation

Red foods at Juneteenth celebrations—watermelon, strawberry soda, red velvet cake—symbolize the bloodshed of ancestors. These symbolic foods connect to the red, black, and green colors adopted during the civil rights era to represent Black liberation.

Freedom songs served as sonic bridges between eras. ‘We Shall Overcome’ during civil rights marches echoed the spirituals sung during emancipation celebrations a century earlier, using similar melodic structures and themes of perseverance.

Both movements used public space as symbolic territory. Juneteenth picnics in public parks and civil rights sit-ins at lunch counters shared a common purpose: claiming space in a society that attempted to restrict Black movement and gathering.

10. Economic Justice as Freedom’s Foundation

Martin Luther King Jr.’s final campaign before his 1968 assassination focused on economic rights. The Poor People’s Campaign demanded jobs, income, and housing for all Americans—recognizing that political rights without economic opportunity created hollow freedom.

This economic focus mirrored the concerns of the post-emancipation era. Freed people consistently identified land ownership and fair wages as essential components of true freedom, recognizing political rights alone wouldn’t sustain their communities.

Both movements confronted the uncomfortable truth that America’s prosperity was built partly on unpaid and underpaid Black labor. From plantation economies to segregated workplaces, economic justice remained central to full freedom—a thread connecting Juneteenth to modern movements for living wages and economic equity.

11. Joy as Radical Resistance

Juneteenth celebrations historically combined solemn remembrance with exuberant joy. Dancing, music, and feasting weren’t just additions to freedom celebrations—they were essential expressions of humanity denied under slavery.

Civil rights activists similarly incorporated joy amid struggle. Freedom songs weren’t just protest tools but expressions of cultural pride and spiritual resilience, often sung in moments of greatest danger.

Black joy itself became political in contexts where dehumanization was the norm. When systems attempted to reduce Black Americans to labor or problems, the simple act of celebrating, laughing, and creating beauty became radical. Both movements understood that liberation included not just freedom from oppression, but freedom to fully express human joy.

12. The Long Road to National Recognition

Juneteenth’s journey to federal holiday status took over 150 years. Texas recognized it first in 1980, with other states gradually following suit over four decades.

The 2020 racial justice protests following George Floyd’s murder created renewed momentum. Many Americans learned about Juneteenth for the first time during this period of national reckoning with racial history.

President Biden signed legislation making Juneteenth a federal holiday on June 17, 2021. This recognition represented both progress and paradox—a celebration of how far America had come alongside acknowledgment of how long overdue this recognition was, echoing the delayed freedom Juneteenth itself commemorates.

13. Civil Rights Icons Honoring Emancipation’s Legacy

Rosa Parks regularly participated in Juneteenth celebrations in Detroit after moving north. Her understanding of resistance didn’t begin with her bus protest but was shaped by generations of freedom struggles dating back to emancipation.

John Lewis explicitly connected civil rights work to the unfulfilled promises of emancipation. His speeches often referenced ancestors who were enslaved, drawing strength from their resilience while fighting for the freedoms they were denied.

Fannie Lou Hamer, herself the daughter of sharecroppers born to formerly enslaved parents, embodied this direct connection. Her famous testimony about voting rights barriers linked her personal experience to both the promise of emancipation and its systematic denial, showing how civil rights leaders lived this historical continuity.

14. Contemporary Movements Drawing Historical Strength

Black Lives Matter activists have explicitly connected their movement to both Juneteenth and civil rights traditions. Many BLM protests incorporate Juneteenth celebrations as reminders that today’s racial justice work continues a long historical struggle.

Modern voting rights campaigns directly reference both Juneteenth and civil rights era voting struggles. When Georgia activists fought voter suppression laws in 2021, they deliberately invoked the language and tactics of previous generations.

Prison reform advocates highlight the 13th Amendment’s exception clause that allowed prisoner slavery. Their work connects the dots between Juneteenth’s incomplete emancipation, civil rights era mass incarceration, and today’s prison industrial complex—showing how freedom remains unfinished business across generations.

15. Teaching Complete American History

American history textbooks traditionally separated slavery from civil rights, presenting them as disconnected episodes rather than continuous struggle. This fragmentation made it harder to understand how systems of oppression evolved and persisted.

Educators now increasingly teach Juneteenth and civil rights as connected chapters in a longer freedom narrative. This approach helps students recognize patterns in American history and understand contemporary issues in proper context.

Learning this fuller history challenges simplified national narratives. Understanding Juneteenth means confronting delayed freedom; understanding civil rights means acknowledging systemic resistance to equality. Together, they present a more honest picture of America’s journey—one that honors those who pushed the nation closer to its ideals despite tremendous opposition.