American military history books often highlight the same familiar faces while leaving countless remarkable heroes in the shadows. These overlooked patriots—many of them women, people of color, and those from marginalized groups—changed the course of American warfare through their courage and sacrifice. Their stories reveal a richer, more diverse military legacy than what’s typically taught in classrooms across the country.

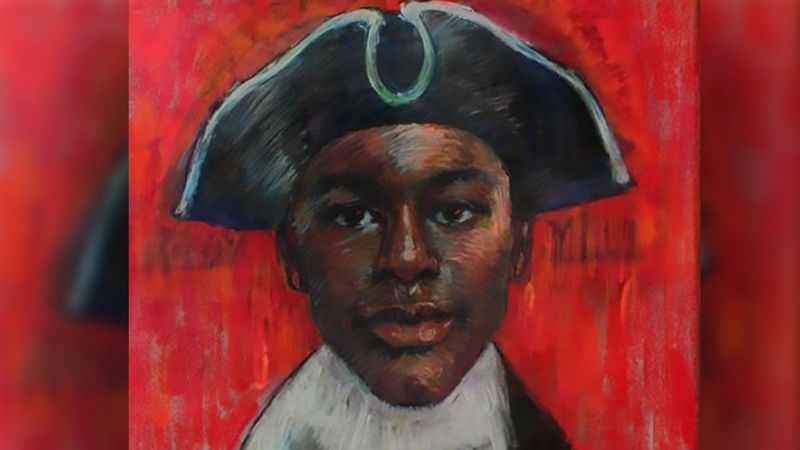

1. Crispus Attucks (1723–1770)

Standing tall in the face of British soldiers, Attucks became America’s first martyr before the country even existed. His mixed African and Native American heritage made him an unlikely revolutionary hero, yet his death ignited the flame of rebellion.

Formerly enslaved and working as a sailor and rope maker in Boston, Attucks joined protesters on that fateful March evening in 1770. When British soldiers opened fire on the crowd, he was the first to fall.

Patriots immediately recognized his sacrifice, with his funeral drawing thousands. Yet as America crafted its founding mythology, Attucks’ contribution gradually faded from prominent historical accounts.

2. Peter Salem (1750–1816)

At the Battle of Bunker Hill, as British forces advanced uphill, a formerly enslaved man named Peter Salem changed American history with a single shot. When British Major John Pitcairn shouted for the rebels to surrender, Salem’s bullet found its mark, killing the officer and helping turn the tide of battle.

Born into bondage in Massachusetts, Salem had been freed to serve in the Continental Army. He fought in numerous key battles including Lexington, Concord, and Saratoga.

Though initially celebrated and immortalized in John Trumbull’s famous painting of Bunker Hill, Salem later fell into obscurity, dying in poverty despite his heroic contributions to American independence.

3. Deborah Sampson (1760–1827)

Wrapped in bandages to conceal her wounds, Sampson treated her own injuries rather than risk discovery as the only woman fighting in her unit. Standing at 5’9″ with strong features that helped her pass as male, she enlisted as “Robert Shurtleff” in 1782 and served for over a year in the Continental Army.

Her deception only ended when she contracted fever and lost consciousness. The doctor who discovered her secret kept it confidential, allowing her an honorable discharge.

Unlike many forgotten heroes, Sampson later toured America telling her story and became one of the first women to receive a military pension, though her full contributions remained underappreciated for centuries.

4. Cathay Williams (1844–1893)

After years serving as a cook and laundress for Union troops during the Civil War, Williams made a bold decision that would write her into the hidden pages of military history. In 1866, she became the first African American woman to enlist in the Army—by pretending to be a man named “William Cathay.”

Despite experiencing the harsh realities of frontier life with the Buffalo Soldiers of the 38th Infantry, Williams managed to keep her secret for nearly two years. Her true identity only came to light when illness forced her into a military hospital.

Following her discharge, Williams worked as a cook and seamstress, receiving neither military pension nor recognition during her lifetime for her groundbreaking service.

5. Henry Johnson (1897–1929)

Armed with only a knife and unimaginable courage, Johnson fought off 24 German soldiers in the Argonne Forest during World War I. As a member of the all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment—known as the “Harlem Hellfighters”—Johnson stood just 5’4” but possessed the heart of a giant.

When Germans attacked his sentry post and wounded his fellow soldier, Johnson jumped into action. Despite being wounded 21 times himself, he kept fighting until the enemy retreated.

France immediately awarded him their highest honor, the Croix de Guerre, but America withheld proper recognition until 2015—86 years after his death—when President Obama posthumously awarded him the Medal of Honor.

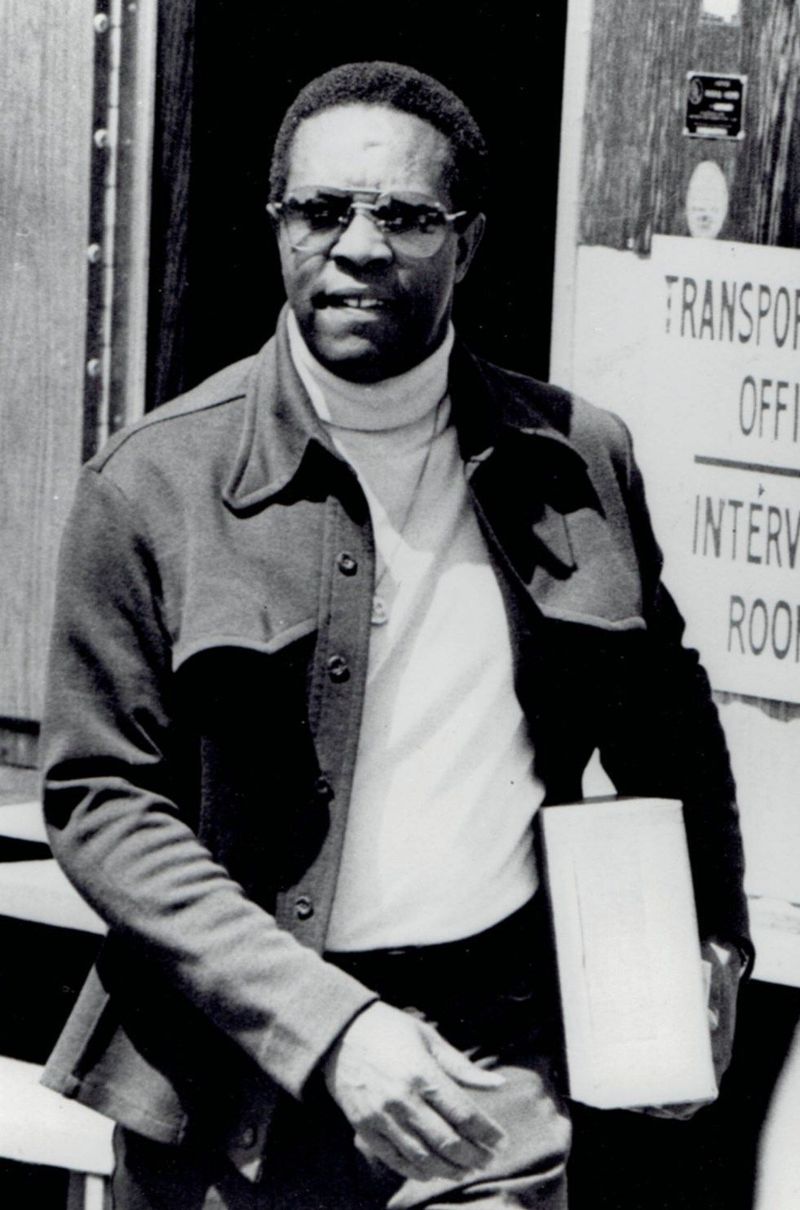

6. Eugene Bullard (1895–1961)

Soaring through the clouds above France, Bullard made history as the first African American combat pilot—though he had to leave his own country to do it. After facing racial discrimination in the U.S. military, Bullard joined the French Foreign Legion and later the French flying corps.

His remarkable aerial combat record included shooting down two enemy aircraft and flying more than 20 combat missions. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre among other decorations.

After WWI, Bullard became a Paris nightclub owner and later a spy for the French Resistance during WWII. America never recognized his pioneering aviation achievements during his lifetime, and his story remains absent from most U.S. history books.

7. Ola Mildred Rexroat (1917–2017)

Nicknamed “Rexy” by her fellow pilots, this Oglala Sioux woman navigated two worlds when she became the only Native American to serve in the Women Airforce Service Pilots during WWII. Growing up on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Rexroat learned determination early, using her secretarial job savings to pay for flying lessons.

As one of the WASPs, she towed targets for live anti-aircraft artillery practice—an incredibly dangerous assignment that male pilots often refused. She also tested repaired aircraft and transported military personnel.

After the war, Rexroat continued serving her country as an air traffic controller for the Federal Aviation Administration until retirement, her pioneering aviation career largely unrecognized.

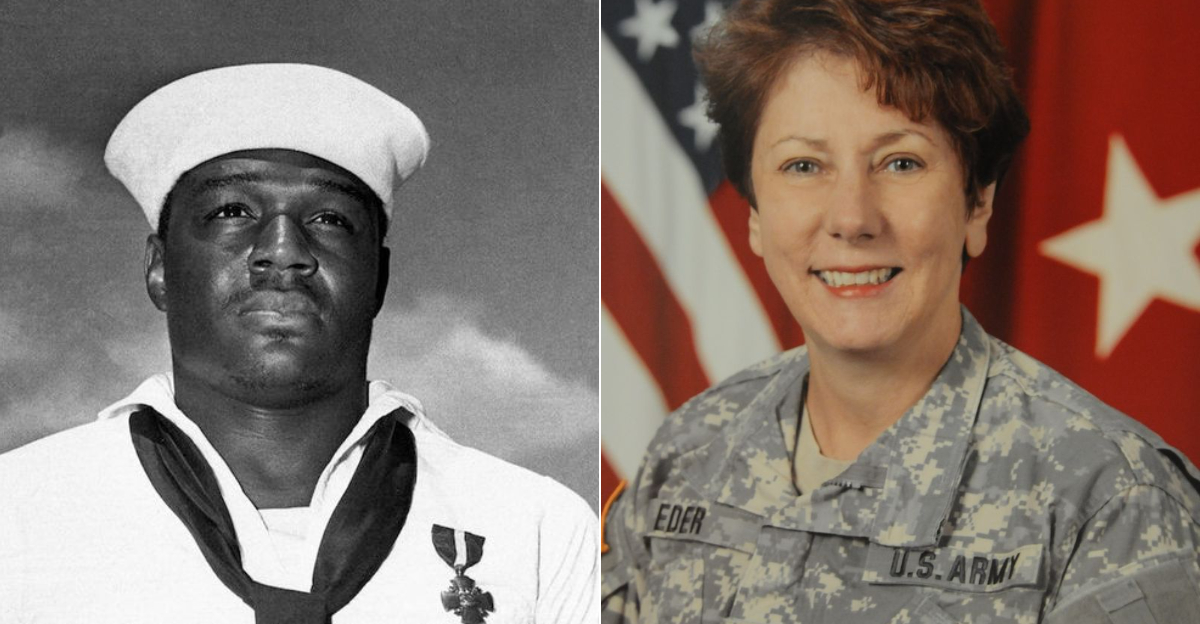

8. Doris “Dorie” Miller (1919–1943)

Amid the chaos of Pearl Harbor, Miller abandoned his mess attendant duties and raced to the deck of the USS West Virginia. Though never trained on anti-aircraft weapons due to racial segregation policies, he instinctively manned a .50 caliber machine gun and reportedly shot down several Japanese planes.

Between firing bursts, he carried wounded sailors to safety, including the ship’s mortally wounded captain. His extraordinary courage earned him the Navy Cross—the first awarded to an African American sailor.

Miller died two years later when his ship was torpedoed in the Pacific. Despite decades of advocacy, the Pentagon didn’t upgrade his award to the Medal of Honor until 2022, nearly 80 years after his death.

9. The Six Triple Eight (6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion)

Eight hundred African American women stood in formation in Birmingham, England in 1945, ready to tackle what seemed impossible: a two-year backlog of mail for American troops. The 6888th—the only all-Black, all-female battalion deployed overseas during WWII—operated under their motto: “No Mail, Low Morale.”

Led by Major Charity Adams, they worked around the clock in three shifts, processing up to 65,000 pieces of mail daily in unheated, rat-infested warehouses. They completed their six-month assignment in just three months.

Despite their remarkable efficiency, these women returned home without fanfare or recognition. It took until 2022 for them to receive the Congressional Gold Medal, America’s highest civilian honor.

10. Roy Benavidez (1935–1998)

“You’re dead,” doctors told Master Sergeant Benavidez after a 1968 rescue mission in Vietnam left him with 37 puncture wounds, exposed intestines, and a broken jaw. They were zipping him into a body bag when he spat in the doctor’s face to prove he was alive.

Earlier that day, the Green Beret had jumped from a helicopter into heavy enemy fire to rescue a 12-man team. For six hours, despite devastating injuries from bullets, bayonets, and shrapnel, he fought off Vietnamese forces while loading wounded comrades onto evacuation helicopters.

Though initially denied proper recognition due to lost paperwork, President Reagan finally presented him with the Medal of Honor in 1981, calling his actions “beyond the call of duty.”

11. Hazel Lee (1912–1944) & Maggie Gee (1923–2013)

When most Chinese American women faced limited opportunities, Lee and Gee took to the skies as two of the only Asian American female pilots in WWII. Lee, the daughter of immigrants, earned her pilot’s license in 1932 and later ferried military aircraft across the country as part of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).

Gee, a Berkeley math major, joined the WASP at just 20 years old. Both women faced dual discrimination as Asians and as women in aviation.

Lee died tragically in a runway collision while delivering a P-63 fighter plane. Gee survived the war, becoming a physicist at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory. Neither received military benefits until Congress retroactively granted veteran status to WASPs in 1977.

12. Colonel Fred Cherry (1928–2016)

For seven years, Cherry endured torture, isolation, and racial abuse in North Vietnamese prison camps. As the first African American fighter pilot captured during the Vietnam War, he faced special cruelty from captors who tried to exploit America’s racial divisions for propaganda.

Despite broken bones, untreated injuries, and solitary confinement, Cherry refused to denounce his country. His captors placed him with a white POW named Porter Halyburton, hoping to create tension. Instead, the two formed a life-saving friendship, with Halyburton helping nurse Cherry back to health.

After his 1973 release, Cherry continued serving in the Air Force until retirement as a colonel, though his extraordinary resilience received little public recognition until decades later.

13. Lieutenant Colonel Martha McSally

Strapped into the cockpit of her A-10 Thunderbolt II—nicknamed the “Warthog”—McSally made history in 1995 as the first American woman to fly in combat. Her missions over Iraq and Kuwait shattered one of the military’s last gender barriers.

A distinguished Air Force Academy graduate and champion triathlete, McSally later took on an even more formidable opponent: the Pentagon itself. She successfully challenged military policies requiring servicewomen to wear traditional Islamic coverings when off-base in Saudi Arabia, arguing they discriminated against female personnel.

Despite her groundbreaking career and later service as a U.S. Senator from Arizona, McSally’s military achievements remain less celebrated than her male counterparts who pioneered aviation firsts.

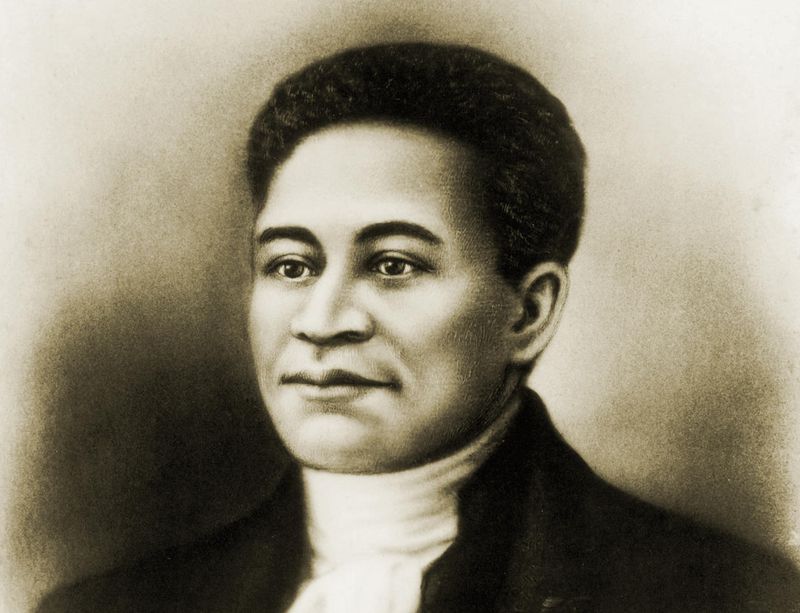

14. Major General Mari K. Eder

While male generals dominated military headlines, Eder quietly revolutionized how America’s armed forces communicate in the digital age. As one of the highest-ranking women in Army history, she transformed military public affairs from simple press releases to sophisticated information operations essential to modern warfare.

Her pioneering work in psychological operations and strategic communications came during pivotal moments in Iraq and Afghanistan. Eder developed frameworks for countering enemy propaganda and disinformation that remain fundamental to military doctrine today.

Despite authoring definitive books on military communication strategy and breaking numerous gender barriers, Eder’s contributions remain largely unknown to the American public compared to battlefield commanders of similar rank.

15. Captain Kristen Griest & Lieutenant Shaye Haver

Muddy, exhausted, and pushing beyond human limits, Griest and Haver made military history in 2015 as the first women to complete Army Ranger School—arguably the military’s most physically demanding training program. For 62 punishing days, they endured minimal food and sleep while carrying 100-pound packs through swamps, mountains, and forests alongside their male counterparts.

Both West Point graduates, they faced intense scrutiny amid debates about women in combat roles. Some critics claimed standards had been lowered, allegations the Army firmly denied.

Their achievement opened the door for women in special operations forces, though their groundbreaking success received only brief media attention before fading from public consciousness despite its profound impact on military gender integration.