Jack Lemmon’s face could tell a thousand stories without saying a word. From his expressive eyebrows to his nervous energy, he brought characters to life like few actors before or since. His ability to seamlessly transition between gut-busting comedy and heart-wrenching drama made him one of Hollywood’s most beloved talents for over four decades.

1. Some Like It Hot (1959)

Dressed in drag and on the run from mobsters, Lemmon’s Jerry/Daphne delivers comedic perfection with every batting eyelash. His transformation from reluctant cross-dresser to someone who genuinely enjoys being Daphne showcases his physical comedy prowess.

The chemistry between Lemmon and Marilyn Monroe crackles with electricity, but it’s his deadpan delivery that steals the show. Who could forget his immortal line after being proposed to: “I’m a man!” followed by Joe E. Brown’s perfect retort.

Director Billy Wilder knew exactly how to harness Lemmon’s manic energy, creating one of cinema’s most beloved comedic performances that still leaves audiences in stitches decades later.

2. The Apartment (1960)

Lemmon’s portrayal of C.C. Baxter, a corporate climber who lends his apartment to executives for their extramarital affairs, balances heartbreak and humor with remarkable precision. His hangdog expressions reveal a decent man trapped in an indecent arrangement.

When he falls for elevator operator Fran Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine), Baxter’s moral awakening unfolds with subtle brilliance. The scene where he strains spaghetti with a tennis racket reveals Lemmon’s gift for making ordinary moments extraordinary.

His second collaboration with director Billy Wilder earned him an Oscar nomination and cemented his reputation as an actor who could make you laugh and break your heart in the same breath.

3. Days of Wine and Roses (1962)

Lemmon’s devastating turn as Joe Clay, a PR man spiraling into alcoholism, shattered his comedy-only image. His performance captures addiction’s insidious progression with unflinching honesty – from charming social drinking to desperate, sweaty withdrawal.

The greenhouse destruction scene remains one of cinema’s most harrowing moments, with Lemmon’s frantic search for hidden liquor revealing addiction’s animalistic desperation. His chemistry with Lee Remick creates a believable couple whose love drowns in alcohol.

Director Blake Edwards stripped away Hollywood glamour to show alcoholism’s ugly reality. Lemmon’s willingness to appear so vulnerable – trembling, weeping, begging – demonstrated his fearless commitment to emotional truth regardless of how unflattering it might appear.

4. The Odd Couple (1968)

Neurotic neat freak Felix Ungar moves in with slovenly sportswriter Oscar Madison after his wife kicks him out. Lemmon embodies Felix’s fussy mannerisms and hypochondria with hilarious precision – from his sinus-clearing honk to his obsessive coaster placement.

The poker game scene showcases his impeccable timing as he serves cuisine that’s too sophisticated for Oscar’s crude friends. Lemmon and Walter Matthau’s contrasting energies create comedic friction that feels genuinely spontaneous.

Felix could have been merely annoying in lesser hands, but Lemmon finds the wounded humanity beneath the neurosis. His portrayal became so iconic that “Felix” entered the lexicon as shorthand for anyone overly concerned with cleanliness and order.

5. Save the Tiger (1973)

Lemmon won his only Best Actor Oscar as Harry Stoner, a once-principled businessman now contemplating arson to save his failing clothing company. His performance excavates the hollow core of the American Dream with quiet devastation.

Harry’s monologue about baseball players from his youth reveals a man mourning not just his lost innocence but an entire generation’s compromise. The hotel room breakdown scene, where Harry finally confronts his moral bankruptcy, showcases Lemmon’s ability to make internal collapse viscerally physical.

Director John G. Avildsen keeps the camera close on Lemmon’s face throughout, capturing every flicker of doubt, shame, and desperation. The performance feels like watching someone drown in slow motion while maintaining a perfect business smile.

6. The China Syndrome (1979)

As Jack Godell, a nuclear plant supervisor who discovers dangerous shortcuts, Lemmon creates a portrait of conscience under pressure. His transformation from company man to whistleblower unfolds with mounting tension, his normally expressive face growing increasingly haunted.

Released just 12 days before the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the film gained eerie prophetic status. Lemmon’s portrayal of technical expertise mixed with moral outrage gives the thriller its emotional core.

The control room scenes showcase his meticulous preparation – Lemmon learned enough about nuclear engineering to make his technical jargon feel authentic. His final standoff, where Godell barricades himself to force public attention, reveals how effectively Lemmon could channel righteous desperation.

7. Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)

Shelley “The Machine” Levene, once a star salesman now desperately clinging to his career, showcases Lemmon’s late-career brilliance. His opening scene in the rain, begging his manager for better leads, creates immediate sympathy for a man whose dignity is evaporating before our eyes.

Surrounded by powerhouse performers like Al Pacino and Kevin Spacey, Lemmon still commands attention through vulnerable desperation rather than scenery-chewing. His celebration after finally closing a sale reveals childlike joy that makes his eventual downfall even more crushing.

Director James Foley keeps David Mamet’s rapid-fire dialogue intact, which Lemmon delivers with the precision of a veteran stage actor. His final confession scene distills a lifetime of disappointment into a few devastating minutes.

8. Grumpy Old Men (1993)

Reuniting with Walter Matthau created pure magic in this late-career gem. As John Gustafson, a retired teacher engaged in a decades-long feud with his neighbor, Lemmon perfectly captures the stubborn pride of aging masculinity.

The ice fishing scenes showcase his physical comedy skills remained intact well into his 60s. Their constant pranks and insults mask a deep friendship that Lemmon conveys through subtle glances that reveal the affection beneath the antagonism.

What could have been merely a vehicle for elderly jokes becomes something more substantial through Lemmon’s performance. He shows how loneliness and pride create barriers that only true friendship – and perhaps romance – can break down, proving his comedic timing remained impeccable throughout his career.

9. The Prisoner of Second Avenue (1975)

Mel Edison’s mental breakdown amid New York City’s chaos allows Lemmon to blend comedy and despair with masterful precision. His performance captures urban anxiety with such authenticity that viewers simultaneously laugh at and ache for this middle-aged man unraveling after losing his job.

The scene where he believes neighbors are stealing his ice cubes showcases Lemmon’s ability to make paranoia both hilarious and heartbreaking. His chemistry with Anne Bancroft as his supportive but exhausted wife creates a believable marriage under extreme stress.

Based on Neil Simon’s play, the film gives Lemmon room to physically express Mel’s deteriorating mental state. His transformation from put-together executive to pajama-clad nervous wreck tracking neighborhood sounds provides a master class in controlled performance escalation.

10. Missing (1982)

Based on true events during Chile’s 1973 coup, Lemmon plays Ed Horman, a conservative American businessman searching for his missing son. His transformation from believing in government authority to confronting American complicity in human rights violations unfolds with devastating clarity.

The morgue scene, where Ed methodically searches through photographs of the dead, showcases Lemmon’s ability to convey horror through stillness. His partnership with Sissy Spacek as his daughter-in-law creates a compelling dynamic – political opposites united by love for the same person.

Director Costa-Gavras harnesses Lemmon’s Everyman quality to powerful effect. The audience experiences Ed’s disillusionment in real-time, making the political personal through Lemmon’s eyes, earning him his final Oscar nomination.

11. The Fortune Cookie (1966)

Lemmon’s first pairing with Walter Matthau delivers comedic gold as Harry Hinkle, a TV cameraman who fakes injuries after being knocked over at a football game. His brother-in-law lawyer (Matthau) sees dollar signs, while Harry battles his conscience.

The physical comedy of pretending to be partially paralyzed allows Lemmon to showcase his gift for bodily control. When alone, Harry moves normally, but must instantly revert to invalid mode when anyone enters – creating hilarious near-misses.

Director Billy Wilder’s cynical take on insurance fraud gives Lemmon the perfect vehicle to explore moral compromise. Harry’s growing attraction to the football player who injured him adds emotional stakes to what could have been merely a farce.

12. The Great Race (1965)

Abandoning his usual Everyman persona, Lemmon gleefully embraces villainy as Professor Fate, a mustachioed madman determined to defeat the heroic Great Leslie in an international car race. His performance channels silent film melodrama with exaggerated gestures and facial expressions that still somehow avoid caricature.

The legendary pie fight scene required Lemmon to be hit with over 40 pies – a slapstick marathon he embraced with characteristic professionalism. His chemistry with Peter Falk as his bumbling assistant creates a comedy duo reminiscent of Laurel and Hardy.

Director Blake Edwards gave Lemmon room to indulge his most theatrical instincts. The result is a performance of gleeful malevolence that reveals how much fun Lemmon could have when freed from playing decent, conflicted men.

13. Tuesdays with Morrie (1999)

In his final major role, Lemmon brought dignity and humor to Morrie Schwartz, a sociology professor dying of ALS who reconnects with a former student. His portrayal of physical deterioration is meticulously observed yet never feels like mere mimicry.

Morrie’s declaration that “when you learn how to die, you learn how to live” gains profound resonance through Lemmon’s performance. The actor, in his 70s himself, brings lived experience to Morrie’s reflections on mortality, creating moments of transcendent wisdom.

Working with Hank Azaria as the former student, Lemmon creates a teacher-student dynamic that evolves into something deeper. His ability to find joy amid suffering results in a performance that serves as both Morrie’s epitaph and, unknowingly, Lemmon’s own farewell to acting.

14. The Out-of-Towners (1970)

George Kellerman’s disastrous trip to New York City provides the perfect showcase for Lemmon’s talent for controlled panic. As an Ohio businessman whose job interview becomes a 24-hour nightmare of missed connections, robberies, and rainstorms, his mounting frustration builds with symphonic precision.

The scene where he dictates increasingly unhinged complaints into a tape recorder demonstrates Lemmon’s gift for escalating anxiety. Neil Simon’s script gives him a marathon of misfortunes, each one pushing George closer to hysteria while maintaining audience sympathy.

Sandy Dennis as his eternally optimistic wife provides the perfect counterbalance to Lemmon’s catastrophizing. Their relationship feels genuinely lived-in, making viewers root for this middle-American couple lost in the urban jungle of 1970s New York.

15. JFK (1991)

Lemmon’s brief but pivotal role as Jack Martin demonstrates his ability to make a lasting impression with limited screen time. As a witness with crucial information about the Kennedy assassination, his nervous energy perfectly captures a man caught between conscience and self-preservation.

Oliver Stone’s controversial film benefits from Lemmon’s inherent trustworthiness – when he speaks about conspiracy, viewers instinctively believe him. The interrogation scene showcases his ability to convey fear and moral conflict simultaneously.

Though surrounded by younger stars, the veteran actor commands attention through subtle choices rather than scene-stealing. His performance reminds viewers that Lemmon could create a fully realized character in just a few minutes, bringing his decades of craft to even the smallest roles.

16. The Front Page (1974)

Hildy Johnson, a star reporter trying to leave journalism for marriage, allows Lemmon to showcase his gift for rapid-fire dialogue. The newsroom scenes with Walter Matthau as his manipulative editor crackle with competitive energy and grudging affection.

Based on the classic stage play, the film gives Lemmon room to display his theatrical timing. His portrayal captures the addiction to news that keeps pulling Hildy back despite his best intentions to escape.

Director Billy Wilder, collaborating with Lemmon for the fourth time, understood how to harness the actor’s frantic energy. The prison break sequence demonstrates Lemmon’s ability to maintain verbal precision during physical comedy – exchanging quips while literally running after a story, embodying the journalist’s conflict between professional excitement and personal commitments.

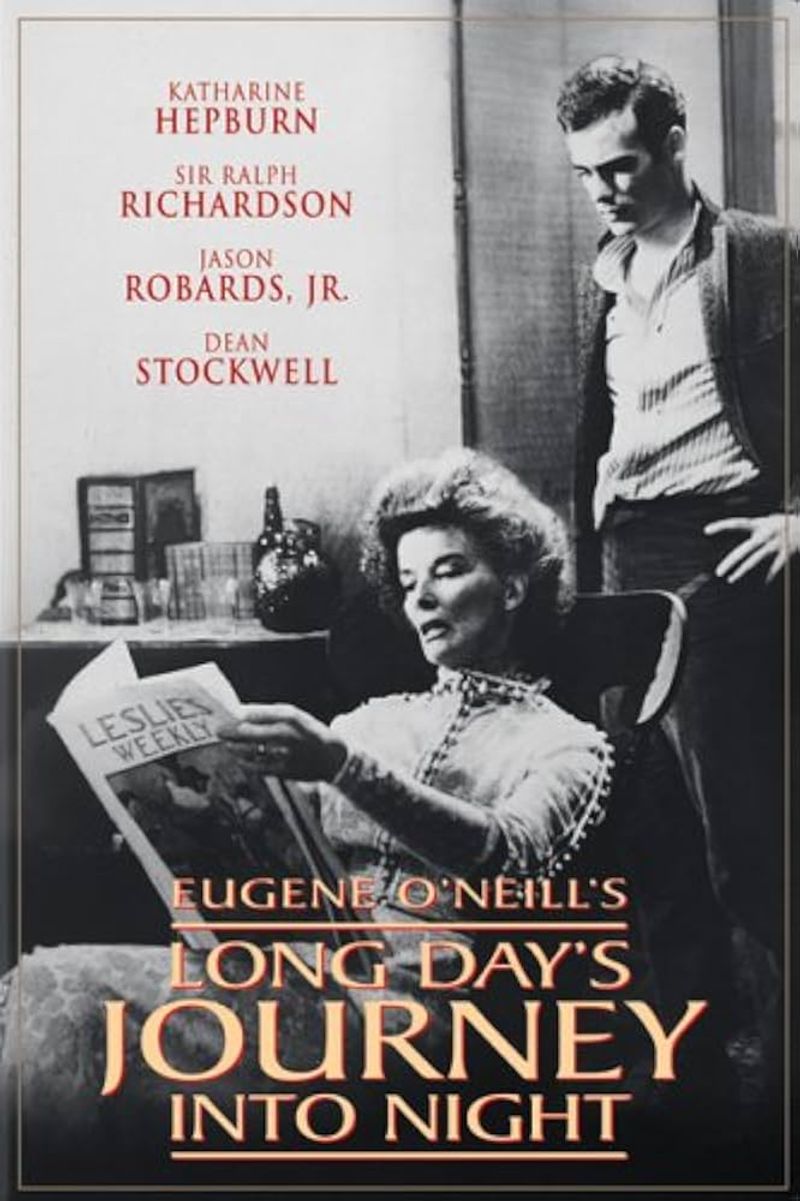

17. Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1962)

Eugene O’Neill’s autobiographical play gives Lemmon his most challenging dramatic role as Jamie Tyrone, the alcoholic older son in a family poisoned by addiction and recrimination. His portrayal of cynical self-loathing creates a character simultaneously sympathetic and repellent.

The late-night confession scene with his younger brother Edmund (played by Dean Stockwell) reveals Jamie’s complex mix of love and jealousy. Lemmon delivers the lengthy monologue with the rhythmic precision of a classical actor while maintaining raw emotional authenticity.

Sharing scenes with Katharine Hepburn and Ralph Richardson pushed Lemmon to new dramatic heights. The performance silenced critics who doubted his serious acting abilities, proving he could handle the most demanding theatrical material with the same excellence he brought to comedy.