When you enjoy your weekend and clock out after eight hours of work, you’re benefiting from a hard-fought battle that cost some people their lives.

In the late 1800s, American workers united to demand humane working conditions during a time when 12-16 hour workdays were standard.

This struggle gave birth to May Day, a holiday celebrated worldwide but largely forgotten in its country of origin.

1. Endless Toil: The Brutal Reality of 19th Century Work

Factory whistles signaled the start of grueling shifts that stretched from sunrise to well past sunset. Most American laborers in the 1800s endured backbreaking 12-16 hour workdays, six days per week, with Sunday as their only reprieve.

Children as young as five worked alongside adults in dangerous conditions. No laws protected workers from exhaustion, injury, or exploitation. Factory owners prioritized production over human dignity, treating workers as disposable resources in America’s rapid industrialization.

2. A Revolutionary Slogan Takes Root

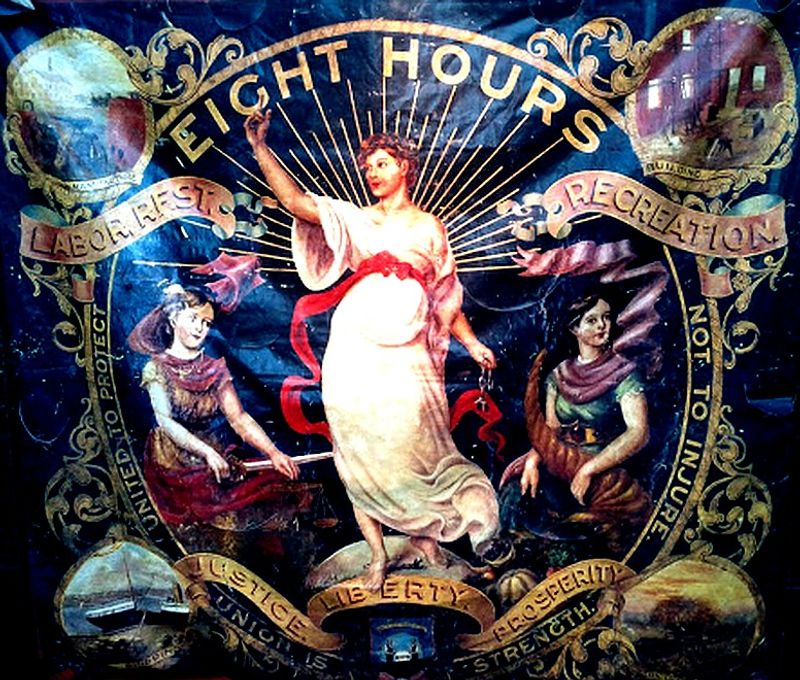

“Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will” echoed through America’s industrial centers. This simple phrase captured workers’ fundamental desire for balanced lives beyond endless toil.

Labor organizers recognized that shorter workdays meant more jobs for the unemployed and healthier lives for everyone. The radical notion that workers deserved time for family, education, and leisure represented a direct challenge to industrial capitalism’s ruthless demands.

3. The Birth of May Day: A Date That Changed History

Labor leaders from across the nation gathered in 1884, plotting a strategy for worker liberation. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions boldly declared May 1, 1886, as the deadline for implementing the eight-hour workday nationwide.

Socialist groups and unions unified behind this date, creating unprecedented solidarity. The choice of May – traditionally a season of renewal – symbolized workers’ hopes for a rebirth of dignity in American labor relations.

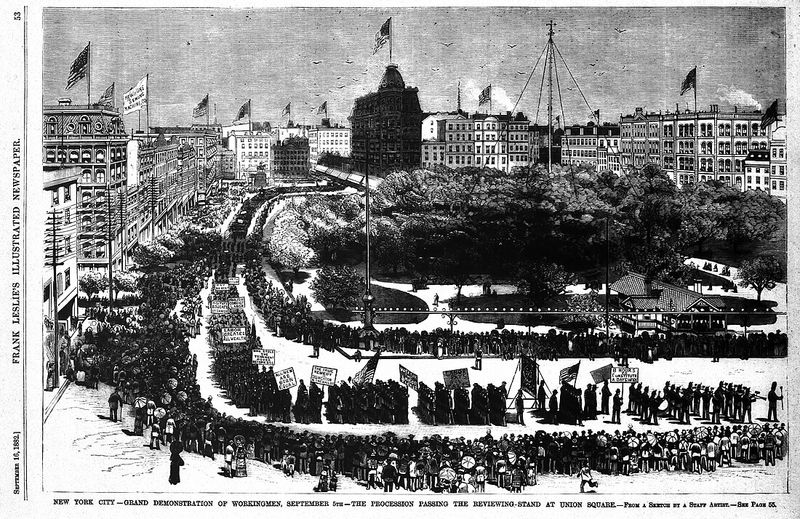

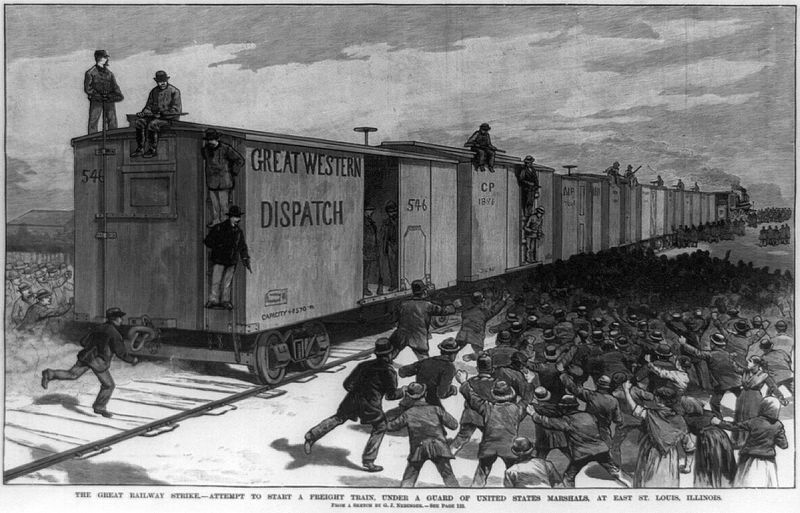

4. America’s First General Strike Rocks the Nation

Streets filled with unprecedented numbers as over 300,000 workers abandoned their posts on May 1, 1886. Factory wheels stopped turning. Deliveries halted. Production ceased across Chicago, New York, Detroit, Milwaukee and beyond.

Workers from diverse backgrounds marched together – immigrants alongside native-born Americans, women beside men. This massive demonstration represented the largest coordinated labor action America had ever witnessed, sending shockwaves through the business establishment.

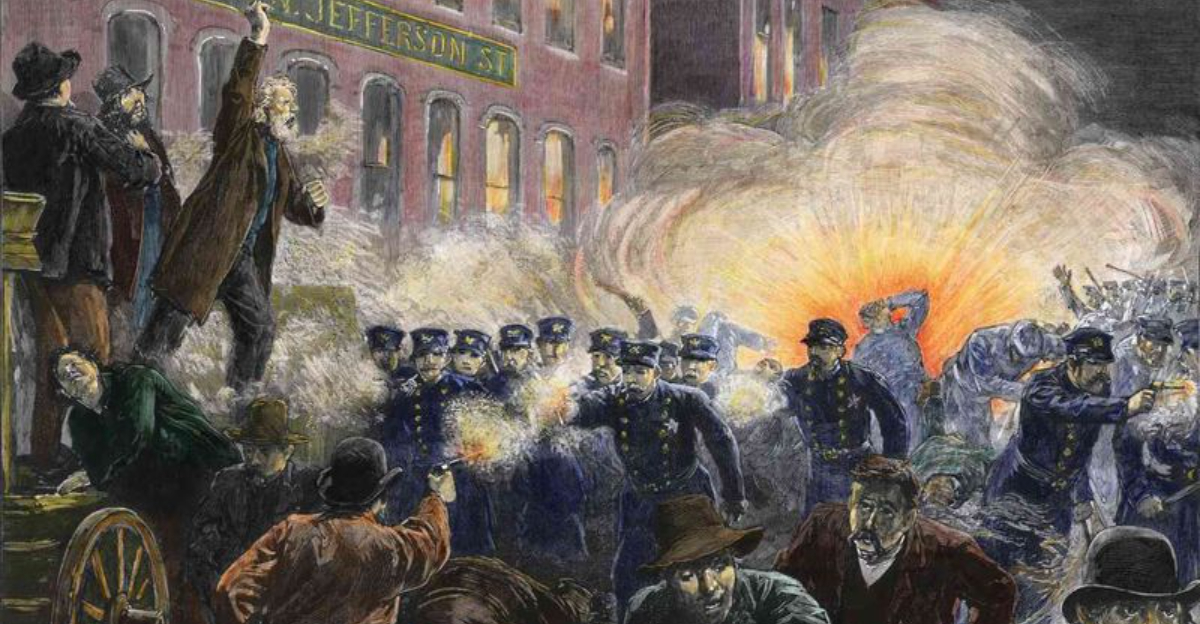

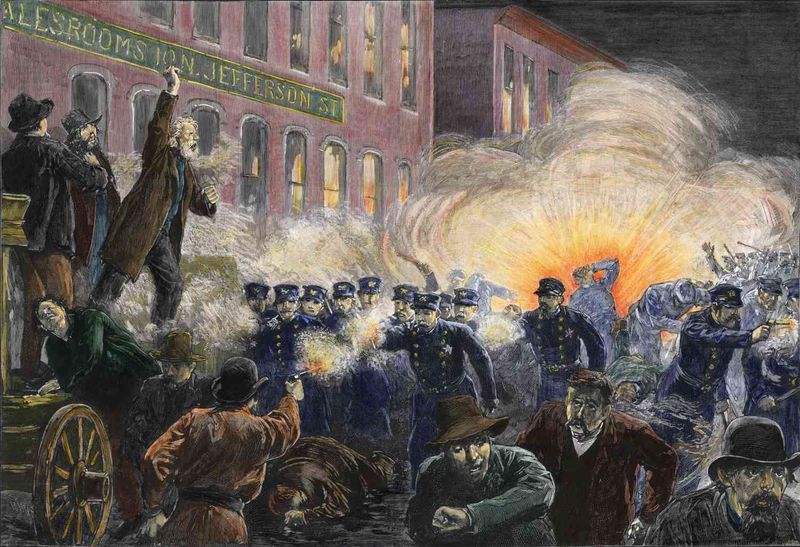

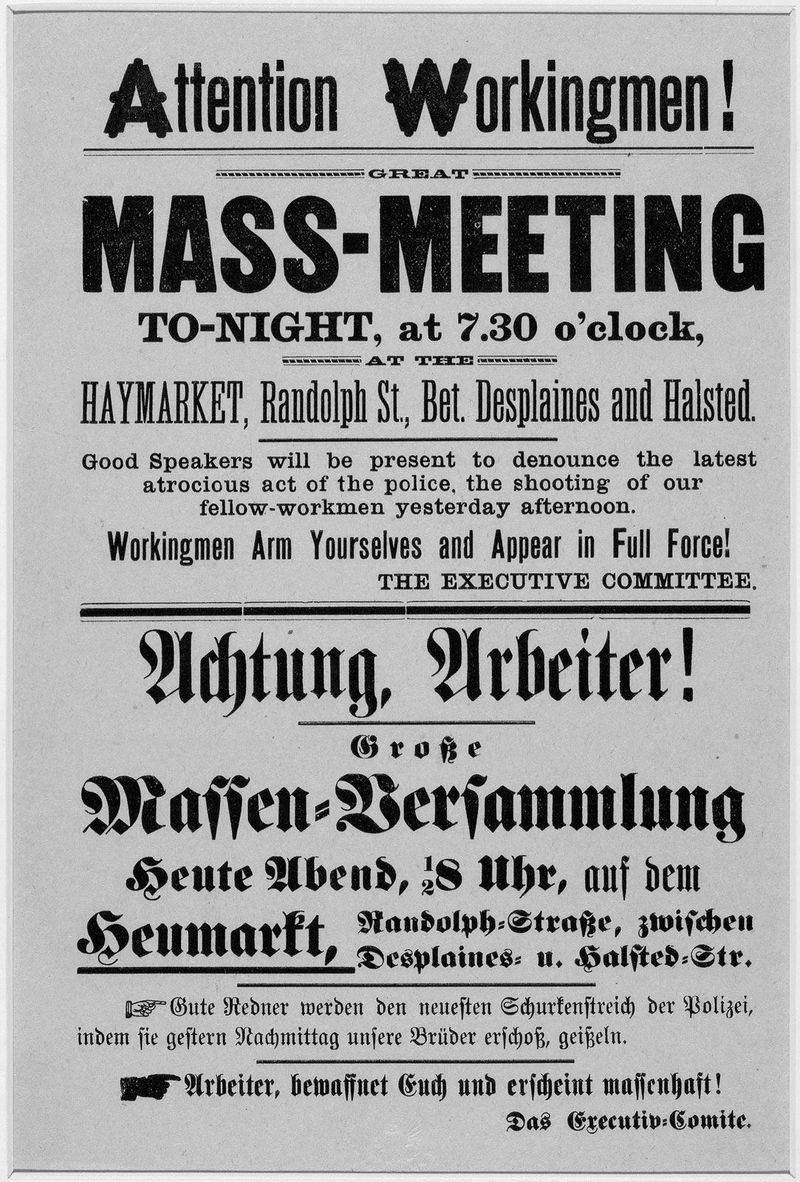

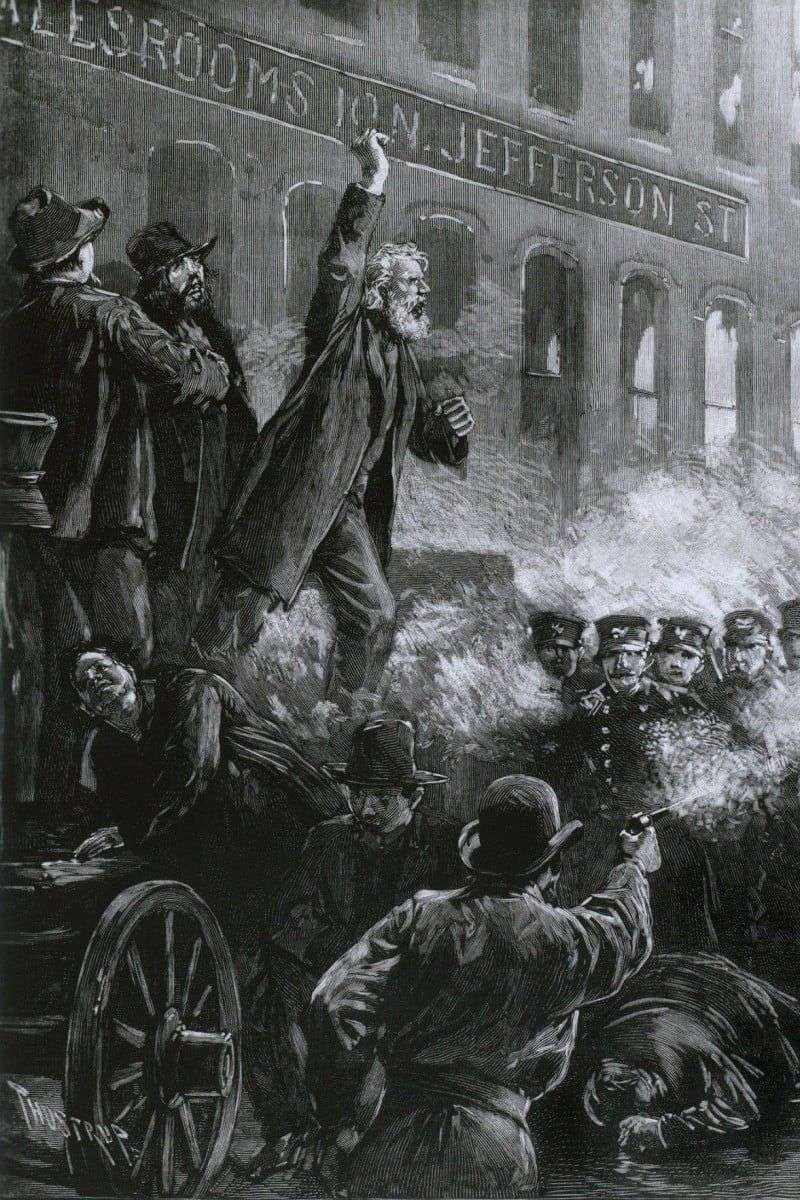

5. Blood in Haymarket Square: Tragedy Strikes the Movement

Rain fell on Chicago’s Haymarket Square as workers gathered peacefully on May 4, 1886. As police moved to disperse the crowd, a bomb suddenly exploded, killing seven officers. Panic erupted as police fired indiscriminately into the crowd.

The bomber’s identity remains unknown to this day. Eight anarchist leaders were arrested despite lack of evidence connecting them to the bombing. Four were ultimately executed in what many historians consider a grave miscarriage of justice.

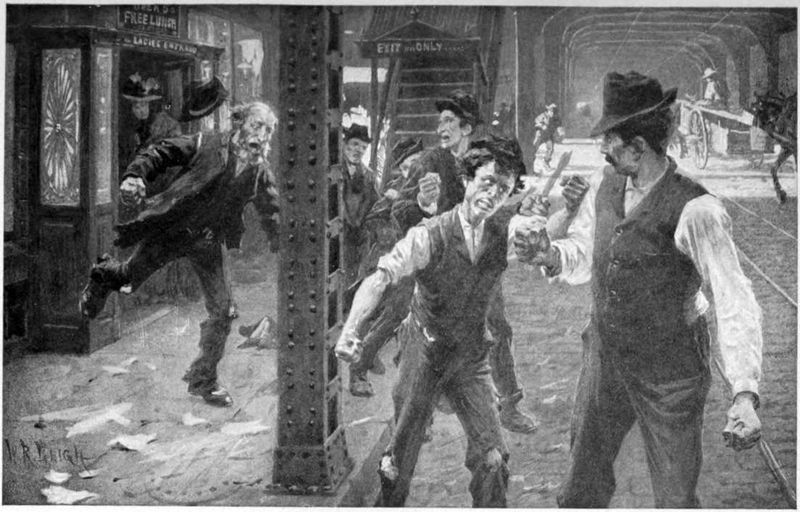

6. Media Backlash Villainizes Worker Rights

Newspaper headlines screamed warnings about “foreign radicals” and “dangerous anarchists” following the Haymarket tragedy. Political cartoons depicted labor organizers as bomb-throwing maniacs, while editorials called for harsh crackdowns on unions.

Many Americans, frightened by sensationalist coverage, turned against the labor movement. Authorities used public fear to justify raids on labor offices and meeting halls. Despite this setback, dedicated organizers continued their work, knowing that justice ultimately stood on their side.

7. May Day Goes Global While America Turns Away

Workers across Europe embraced May 1st as International Workers’ Day in 1889, honoring the martyrs of Chicago’s labor struggle. Red flags and worker solidarity marches became May Day traditions from Paris to Moscow.

Meanwhile, American officials deliberately established September’s Labor Day to sever connections with “radical” May Day. This calculated move reflected government fears of working-class militancy. Today, America stands nearly alone among industrialized nations in not officially recognizing May 1st as Labor Day.

8. Victory Through Persistence: How Eight Hours Became Law

Ford Motor Company shocked the business world in 1914 by adopting the eight-hour day while doubling wages. Their productivity soared, challenging prevailing business wisdom. Union contracts gradually secured shorter hours across industries.

President Roosevelt finally signed the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938, enshrining the 40-hour workweek in federal law. This victory came fifty-two years after the first May Day demonstrations. Workers had persevered through decades of strikes, blacklisting, violence, and setbacks to achieve what once seemed impossible.

9. A United Front: Diversity in the Eight-Hour Movement

Women garment workers, often immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe, marched alongside male factory workers in the fight for shorter hours. Black laborers, despite facing discrimination within some unions, recognized the eight-hour cause as essential to all workers’ dignity.

Skilled craftsmen joined forces with unskilled laborers, overcoming traditional divisions. The movement’s strength came from this unprecedented unity across gender, racial, and occupational lines – challenging the myth that early labor activism was solely the domain of white male workers.

10. May Day’s Modern Relevance in a Changing Workplace

Gig economy workers today face eerily similar conditions to those fought against in 1886 – unpredictable hours, minimal protections, and constant pressure to work longer. Remote employees report working significantly more hours than their office-based predecessors, blurring work-life boundaries.

May Day’s legacy reminds us that workplace rights are never permanently secured. Each generation must defend the eight-hour day and weekend rest that came at such great cost. The struggle continues in new forms, with the fundamental question remaining: do we live to work, or work to live?