The golden age of Hollywood was ruled by five mighty movie studios known as ‘The Big Five.’

From the 1930s through the 1970s, these powerhouses – Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO – controlled everything from the stars they employed to the theaters showing their films.

Their rise to power created the entertainment industry we know today, but their eventual fall transformed Hollywood forever.

1. The Studio System Takes Shape (1930-1935)

Five companies emerged as the titans of Hollywood at the dawn of the 1930s. Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO Pictures established unprecedented control over the film industry through vertical integration.

These studios owned everything – production facilities, distribution networks, and theater chains across America. This complete control meant guaranteed profits and artistic dominance.

The Hays Production Code, implemented in 1934, added another layer of control, regulating what could appear on screen. Under this system, studios manufactured films like factories, with actors, directors, and writers working as contracted employees rather than independent artists.

2. MGM’s Lion Roars Loudest (1936-1942)

MGM Studios reached its majestic peak during this period, boasting it had “more stars than there are in heaven.” Their Culver City lot became a kingdom unto itself, producing lavish musicals and prestigious dramas that defined American cinema.

Stars like Clark Gable, Judy Garland, and Joan Crawford lived under strict seven-year contracts. These agreements controlled everything from their film roles to their personal lives and public images.

Louis B. Mayer, MGM’s fearsome leader, became the highest-paid executive in America, earning an astounding $1.3 million annually—equivalent to over $25 million today. The studio’s technical prowess and production values set industry standards that competitors struggled to match.

3. Wartime Glory and Propaganda (1942-1945)

Pearl Harbor transformed Hollywood overnight. The Big Five studios pivoted to support the war effort, producing patriotic films that boosted morale and promoted American values. Warner Bros. particularly excelled with films like “Casablanca” that mixed entertainment with subtle propaganda.

Movie attendance soared to all-time highs as Americans sought escape from wartime anxiety. Nearly 90 million people—about 65% of the population—went to theaters weekly.

Behind the scenes, studios worked directly with government agencies to craft messaging. Stars like Jimmy Stewart and Clark Gable enlisted for active duty, while others sold war bonds in massive nationwide tours. This era represented the absolute height of the studios’ cultural influence and financial power.

4. The Paramount Decision Earthquake (1948)

May 4, 1948 marked the beginning of the end for the old Hollywood. The Supreme Court handed down its landmark ruling in United States v. Paramount Pictures, forcing the Big Five to sell off their theater chains and ending the practice of block booking.

This antitrust decision shattered the vertical integration model that had made the studios so profitable. No longer could they guarantee exhibition of their films or force theaters to take their entire slate of movies.

RKO and Paramount quickly complied with the ruling, while the other studios fought through appeals. The fallout was immediate and severe—studio profits plummeted as they lost control over distribution, and power began shifting toward independent producers and theater owners for the first time.

5. Television’s Threat Emerges (1950-1955)

A small screen invasion caught Hollywood completely off guard. Television ownership exploded from just 6,000 sets in 1946 to over 12 million by 1951, keeping potential moviegoers comfortably entertained at home.

Weekly theater attendance plummeted nearly 50% between 1948 and 1952. The Big Five responded with technological gimmicks—CinemaScope widescreen at Fox, 3D movies at Warner Bros., and VistaVision at Paramount—all attempts to offer experiences television couldn’t match.

RKO Pictures became the first casualty, struggling under Howard Hughes’ erratic ownership before essentially ceasing production. The remaining studios reluctantly began licensing their film libraries to television networks, trading their prestigious exclusivity for badly needed revenue streams.

6. Epic Gambles and Changing Tastes (1956-1962)

Desperate to win back audiences, studios bet enormous sums on spectacular productions. Films like “The Ten Commandments” and “Ben-Hur” featured thousands of extras and unprecedented budgets, sometimes exceeding $15 million—astronomical figures for the time.

These epic gambles sometimes paid off spectacularly. “Ben-Hur” won 11 Academy Awards and saved MGM from bankruptcy, while others like Fox’s “Cleopatra” became legendary disasters that nearly destroyed their studios.

Meanwhile, audience tastes were changing dramatically. The post-war generation showed less interest in the glossy musicals and historical epics that had been studio staples. Independent films like “Rebel Without a Cause” captured the emerging youth market, signaling that the Big Five were losing touch with changing American culture.

7. The Star System Collapses (1963-1966)

Elizabeth Taylor’s unprecedented $1 million salary for “Cleopatra” signaled a power shift that terrified studio executives. Stars were breaking free from restrictive long-term contracts, demanding creative control and percentages of profits rather than fixed salaries.

Actors like Marlon Brando, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster formed their own production companies. The studio system that had manufactured stars now found itself negotiating with them as equals or even superiors.

This transformation coincided with cultural upheaval across America. Civil rights movements, anti-war protests, and the sexual revolution demanded more authentic storytelling that the formulaic studio approach couldn’t provide. The collapse of the Hays Code censorship system in 1968 would remove the last major element of the old studio control mechanism.

8. Corporate Takeovers Transform Studios (1966-1969)

Wall Street discovered Hollywood in the late 1960s, forever changing the industry’s structure. Gulf+Western purchased Paramount in 1966 for $125 million, transforming a movie studio into a small division of a sprawling conglomerate more concerned with quarterly profits than filmmaking tradition.

The other studios quickly followed: Transamerica Corporation acquired United Artists, Kinney National Services (later Warner Communications) bought Warner Bros., and MGM underwent multiple ownership changes. Only 20th Century Fox remained relatively independent.

These corporate parents viewed film libraries as assets rather than cultural artifacts. They installed business executives in positions once held by movie moguls. The personal touch of founders like Jack Warner and Louis B. Mayer disappeared, replaced by corporate decision-making focused on financial metrics rather than showmanship.

9. New Hollywood Revolution (1969-1975)

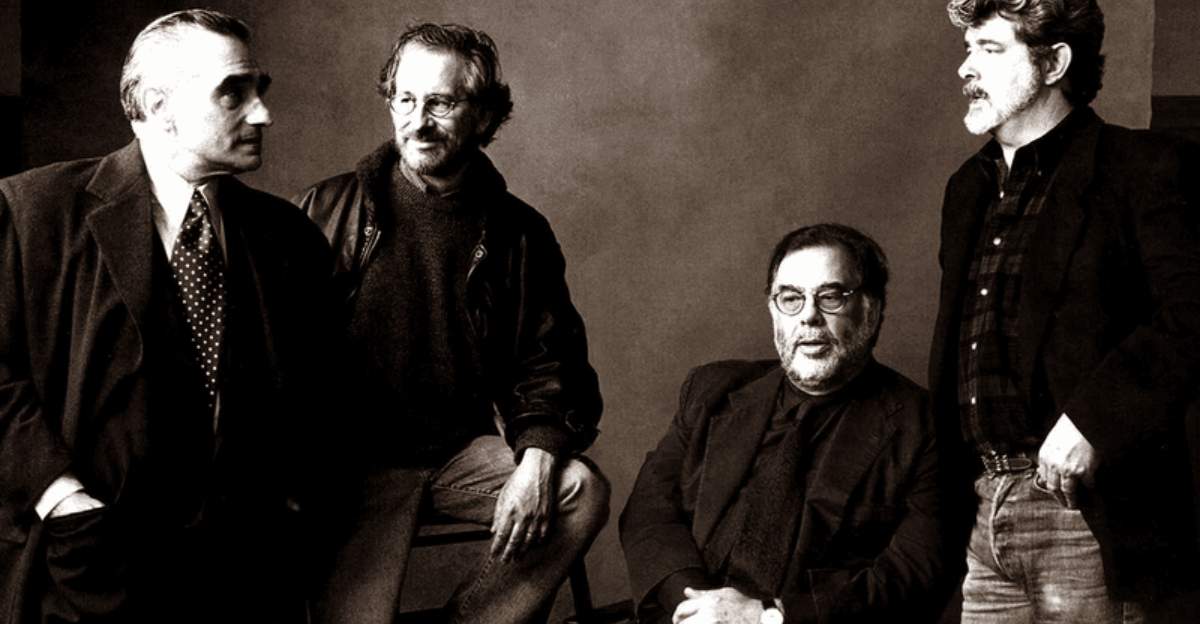

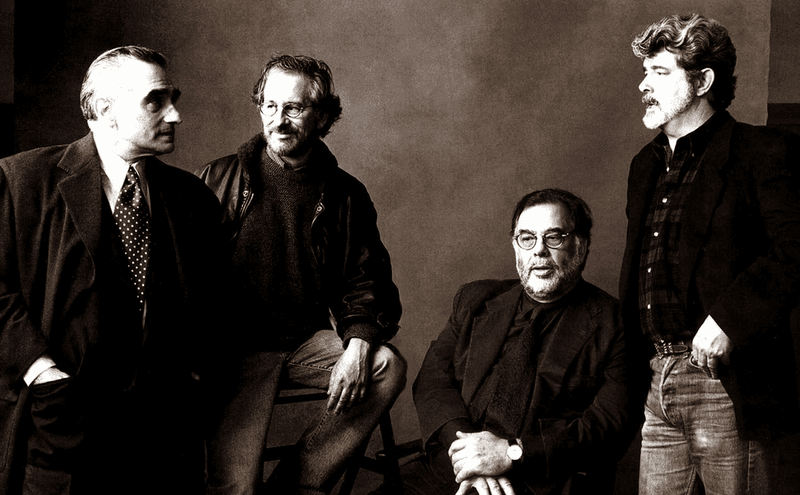

A generation of film school graduates stormed the weakened studio gates. Directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg brought fresh perspectives and European-influenced filmmaking techniques to Hollywood.

Studios, desperate for relevance and hits, took unprecedented risks on young filmmakers. “Easy Rider,” made for just $400,000, grossed $60 million and showed that low-budget, counterculture films could outperform traditional studio fare.

The artistic freedom of this period produced masterpieces like “The Godfather,” “Taxi Driver,” and “Jaws” that redefined American cinema. Ironically, this creative renaissance happened because the Big Five had lost their iron grip on production, allowing directors creative control that would have been unthinkable under the old system.

10. Blockbusters and the Birth of Modern Hollywood (1975-1980)

“Jaws” crashed into theaters in summer 1975, grossing an unprecedented $260 million with a revolutionary wide release strategy and national television advertising. Two years later, “Star Wars” would shatter even those records and transform merchandising into a revenue stream larger than ticket sales.

These blockbusters created the template for modern Hollywood: high-concept, widely marketable films supported by massive marketing campaigns. The Big Five studios, now mostly divisions of larger corporations, embraced this model wholeheartedly.

By 1980, the transformation was complete. Studios focused on financing and distribution rather than production, working with independent producers and directors. The vertically integrated studio system that had dominated for decades was gone, replaced by a new model that continues, with modifications, to this day.