The Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 was one of history’s deadliest pandemics. Unlike anything seen before or since, this devastating illness swept across the globe during World War I, killing more people than the war itself. The virus infected every corner of the world, leaving communities devastated and forever changing how we understand and respond to infectious diseases.

1. Infected roughly 500 million people worldwide—about one-third of the global population at the time—making it the most widespread flu pandemic in history

The scale of infection during the Spanish Flu remains almost unimaginable today. With approximately 500 million people infected globally, the pandemic touched nearly every family and community.

No disease before or since has reached such a high percentage of humanity in such a short time. Ships carried the virus to distant ports, while trains spread it inland across continents.

Rural villages once isolated from global health threats found themselves battling the same invisible enemy as major cities. This unprecedented reach demonstrated how modern transportation had created a new era of pandemic vulnerability.

2. History

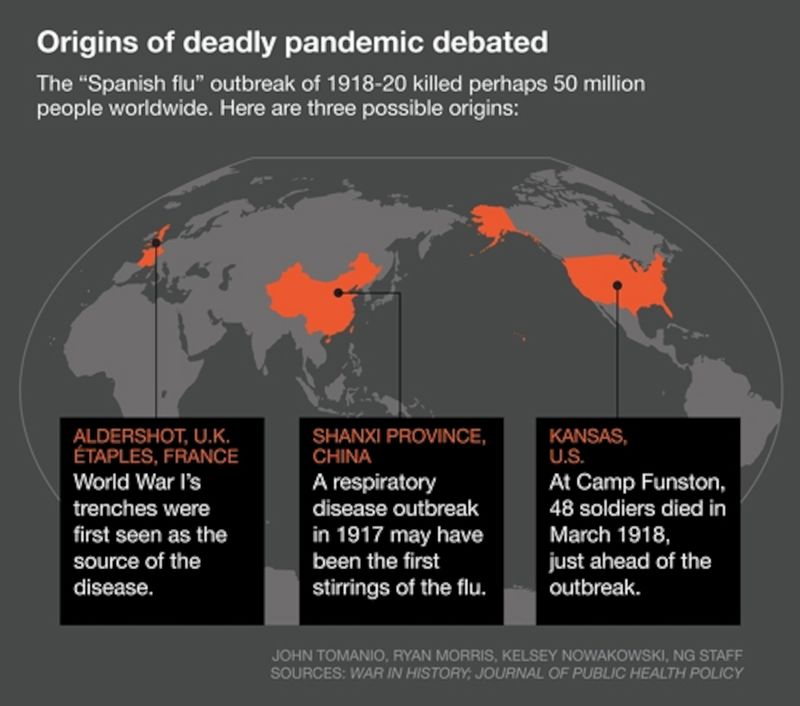

The pandemic’s origins remain debated among historians. While popularly believed to have started in Spain, evidence suggests the first cases appeared at Camp Funston, Kansas, in March 1918 among military personnel.

Some researchers propose alternative theories pointing to origins in France, China, or Britain. The virus spread in three distinct waves, with the deadly second wave beginning in August 1918.

By the time it subsided in 1920, the pandemic had lasted approximately 26 months. Its rapid global spread was unprecedented, reaching even remote Pacific islands and Arctic communities within months of the first outbreaks.

3. Caused an estimated 50 million deaths, with the upper range of some studies reaching 100 million (around 3% of the world’s population)

The death toll of the Spanish Flu dwarfed the casualties of World War I. While 17 million people died in the war, the pandemic claimed at least three times that number.

Modern research suggests the commonly cited figure of 50 million deaths may be too conservative. Some epidemiologists believe the true count reached 100 million—equivalent to the entire population of the United States at that time.

Many deaths went unrecorded, especially in colonial territories and remote regions. This staggering mortality rate means roughly one in every 30 humans alive in 1918 perished from this single disease.

4. Discover Walks

Cities became eerie landscapes as the pandemic peaked. Streets emptied, businesses closed, and public spaces stood abandoned as fear spread faster than the virus itself.

In Philadelphia, one of America’s hardest-hit cities, bodies piled up so quickly that morgues overflowed. Corpses remained in homes for days as funeral services collapsed under the volume. Some families resorted to digging graves themselves.

In India’s Bombay (now Mumbai), mortality reached such extreme levels that traditional funeral pyres burned day and night along the shoreline. The smell of death hung over cities worldwide, creating psychological trauma that survivors would carry for decades.

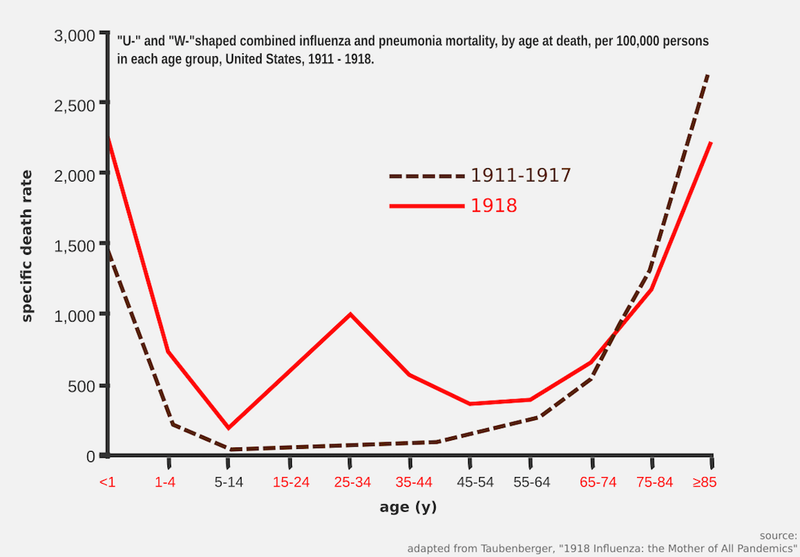

5. Exhibited a “W-shaped” mortality curve, striking not only infants and the elderly but unusually high death rates among healthy young adults (ages 20–40), likely due to cytokine storms over-energizing their immune response

Unlike typical flu seasons that primarily kill the very young and very old (creating a U-shaped mortality curve), the Spanish Flu produced a distinctive W-shaped pattern. The middle peak of this W represented healthy young adults in their prime—precisely those expected to survive.

Medical researchers now believe the virus triggered extreme immune responses called cytokine storms. Paradoxically, stronger immune systems reacted more violently, essentially attacking the body they were meant to protect.

This cruel irony meant military camps filled with young soldiers became death traps. In some units, more men died from influenza than from enemy fire on the battlefield.

6. The second wave (autumn 1918) was far deadlier than the first, with victims succumbing in hours or days of symptom onset, whereas the spring 1918 wave was relatively mild

The pandemic’s initial wave in spring 1918 caused relatively few deaths. Many doctors mistook it for seasonal influenza, not recognizing the looming catastrophe.

By autumn, the virus had mutated into something far more lethal. Victims who appeared healthy at breakfast could be dead by dinner. Military physician reports described patients turning blue from lack of oxygen before drowning in their own fluids.

This second wave killed more people in 24 weeks than AIDS has killed in 24 years. The third wave in early 1919, while less severe than the second, still claimed millions of lives before the pandemic finally began subsiding.

7. Most fatalities resulted from secondary bacterial pneumonia, as there were no antibiotics available—penicillin would not be discovered until 1928

The flu virus itself rarely delivered the final blow. Instead, it weakened victims’ respiratory systems, allowing bacteria to invade the lungs and cause pneumonia.

Without antibiotics, doctors stood helpless as patients’ lungs filled with fluid. They tried desperate measures—blood-letting, oxygen treatments, even injections of strychnine and arsenic—but nothing consistently worked.

Some physicians recommended quinine, aspirin, or alcohol, though these offered little more than comfort. Medical science’s powerlessness against secondary infections meant that once pneumonia developed, death rates exceeded 70% in many hospitals—a condition that today would be routinely cured with common antibiotics.

8. Victims often turned blue (“cyanosis”) and suffocated as their lungs filled with fluid; death could follow within 24–48 hours of severe symptom onset

The most terrifying aspect of the Spanish Flu was how quickly it killed. Victims developed a distinctive blue-purple coloration of the face and extremities—a condition called cyanosis—as their oxygen-starved blood failed to circulate properly.

Survivors described the horror of watching loved ones “drown” on dry land. Lung tissue samples from victims showed massive damage, with lungs filled with bloody, frothy fluid.

Some patients died within hours of the first symptoms. The speed was so shocking that urban legends spread of people who boarded streetcars while healthy and died before reaching their destination—stories that weren’t always exaggerations.

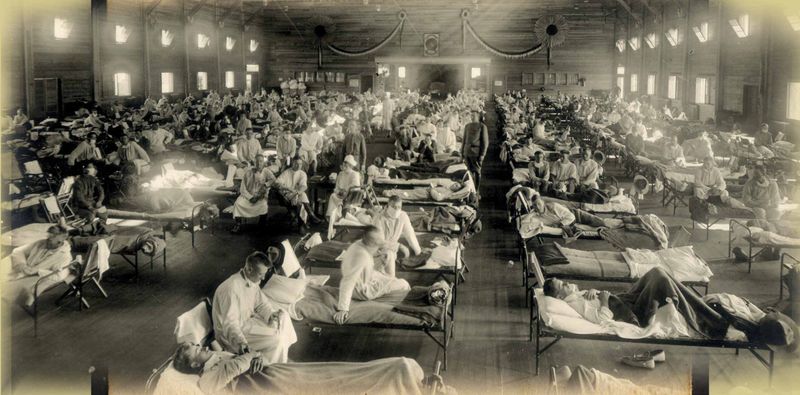

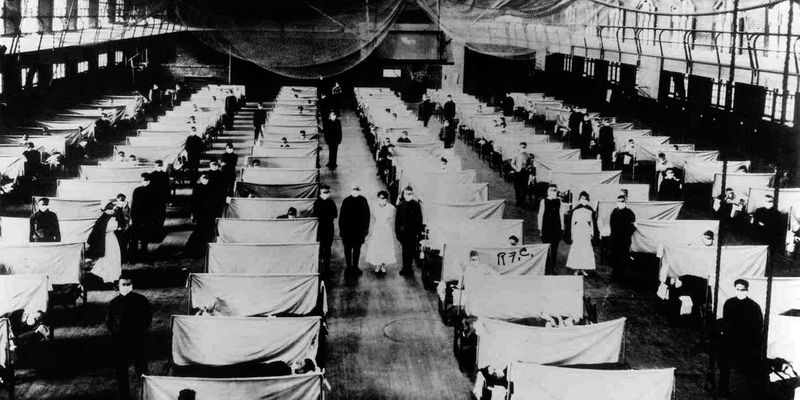

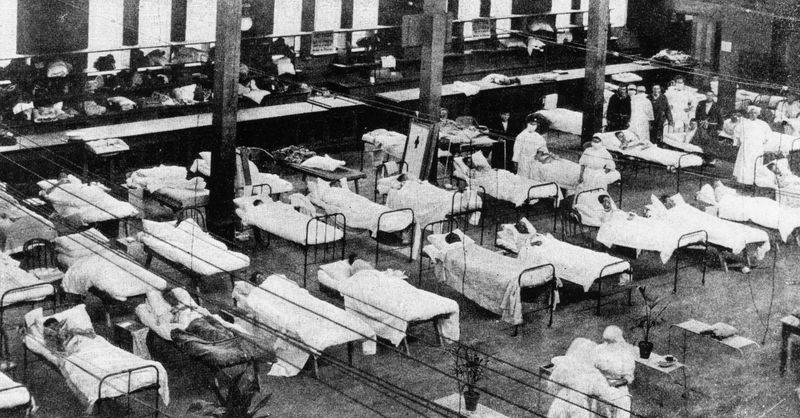

9. With doctors and nurses depleted by World War I, many hospitals were overwhelmed, leading to schools, private homes, and public buildings being converted into makeshift wards, often staffed by medical students

The war had already stretched medical resources to breaking point before the pandemic struck. Many doctors and nurses were serving on battlefields when their skills became desperately needed at home.

Cities converted schools, churches, and community halls into emergency hospitals. Medical students, dentists, veterinarians, and volunteers with minimal training found themselves thrust into frontline healthcare roles.

In Philadelphia, the hardest-hit American city, 4,500 people died in a single week. Desperate officials converted a 400-bed hospital at the city’s Naval Yard to accommodate 1,200 patients, with nursing students working 14-hour shifts until they too fell ill.

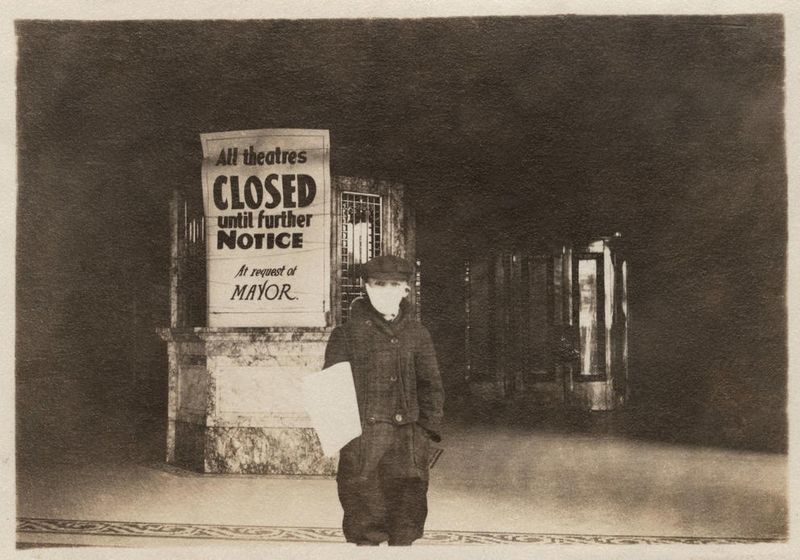

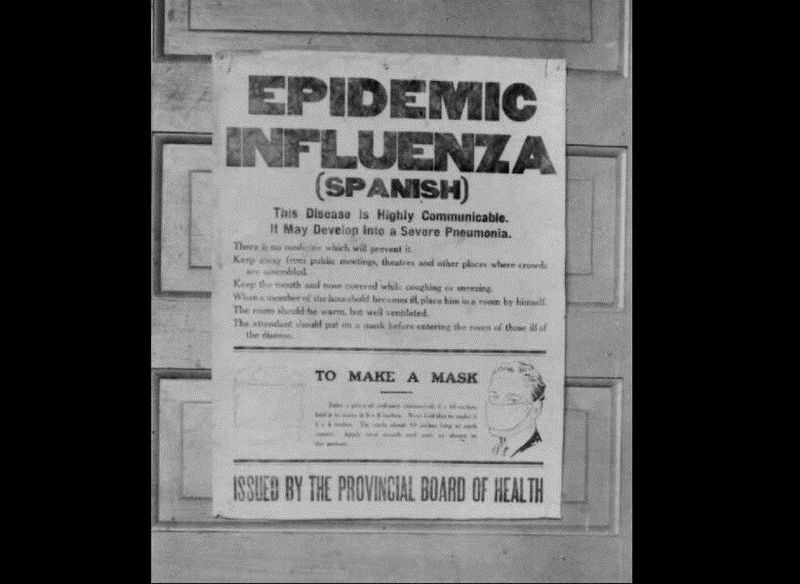

10. Public-health responses included mask mandates, closure of schools, theaters and churches, strict quarantines, and bans on public gatherings—and even spitting was outlawed in many cities

Cities worldwide implemented emergency measures that would seem familiar to modern pandemic survivors. San Francisco created the first mandatory mask law in the United States, with police arresting those who refused to comply.

Many communities banned public funerals, limited store hours, and staggered work shifts to reduce crowding. Some cities created “influenza ordinances” making it illegal to cough or sneeze in public without covering your face.

Telephone operators were deemed essential workers but required to wear masks while working. Public health campaigns promoted handwashing and social distancing with slogans like “Better be ridiculous than dead” to encourage mask-wearing despite social resistance.

11. Wartime censorship in belligerent nations hid the outbreak’s severity; Spain’s neutral press reported freely, giving rise to the misnomer “Spanish” flu

The pandemic’s nickname represents one of history’s great misnomers. Spain had nothing to do with the virus’s origin—the country simply reported honestly about the disease while other nations suppressed information.

Countries fighting in World War I censored news about the outbreak, fearing reports would damage morale or reveal weakness to enemies. Spanish newspapers, under no such restrictions, published detailed accounts of the illness, including reports that King Alfonso XIII had fallen seriously ill.

This created the false impression that Spain was uniquely affected. The Spanish, meanwhile, called it the “French Flu,” while Brazilians named it the “German Flu,” each blaming foreign origins for their suffering.

12. Troop movements in World War I accelerated global spread, carrying the virus to remote areas including Pacific islands and Alaskan villages

World War I created perfect conditions for viral spread. Military camps packed thousands of men into tight quarters, while troop ships became floating incubators where the virus passed easily between soldiers.

As infected troops deployed globally, they carried the disease to every continent. Remote communities with no previous exposure to influenza suffered catastrophic losses.

In Alaska’s Bristol Bay, 40% of the adult population died within months. The entire village of Brevig Mission lost 72 of its 80 residents in just five days. Western Samoa lost 22% of its population, while other Pacific islands saw up to 90% infection rates—devastating indigenous communities that had survived for centuries in isolation.

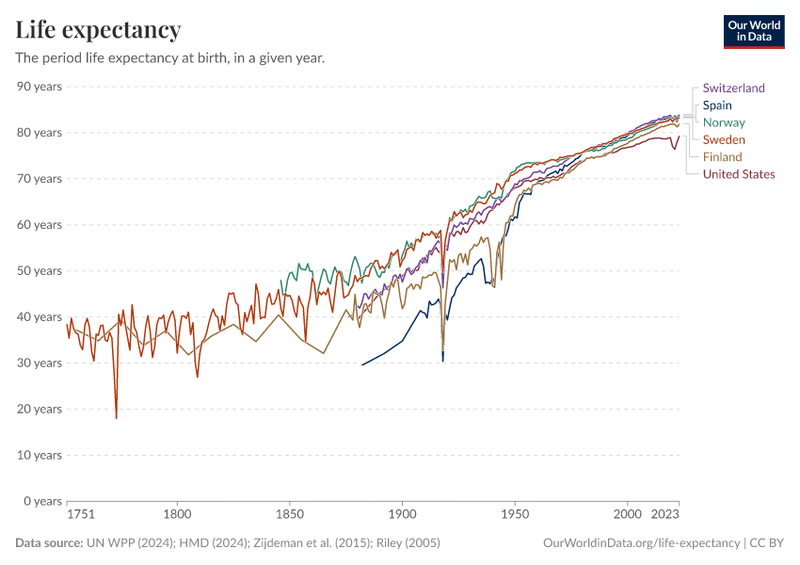

13. In the United States, life expectancy dropped by 12 years in 1918 due to the pandemic’s carnage

Before 1918, Americans born that year could expect to live about 51 years. The pandemic’s devastating impact slashed this figure to just 39 years—the largest single-year drop in American history.

This statistical plunge reveals the extraordinary toll on young adults. Healthy 25-year-olds dying by the thousands created demographic ripples still detectable in population data today.

The pandemic left an estimated 21,000 American children completely orphaned. Communities struggled to care for these children, creating new social welfare programs. The massive loss of workers also contributed to labor shortages that accelerated women’s entry into the workforce and helped shape the economic boom of the 1920s.

14. India bore the heaviest national toll, with an estimated 12 million deaths—the highest for any country

While the pandemic struck globally, no nation suffered more than India. Approximately 5% of India’s entire population perished—equivalent to 17 million Americans dying today.

Colonial authorities provided minimal assistance to Indian communities. Many villages lost so many adults that agricultural production collapsed, triggering famines that caused even more deaths.

The British colonial government actually continued exporting Indian grain throughout the crisis. In some regions, mortality reached 10%, decimating entire communities. The staggering death toll contributed to growing Indian resistance to British rule, becoming one factor in the independence movement that would eventually end colonization.

15. There were no vaccines or antivirals available; the first licensed flu vaccine would only appear in the 1940s, underscoring how helpless medical science was against the strain

Medical professionals in 1918 faced the pandemic with virtually no effective tools. Viruses themselves had not yet been visualized with microscopes, and many doctors still believed influenza was caused by bacteria.

Desperate for solutions, physicians tried everything from blood-letting to bizarre concoctions like turpentine on sugar cubes. Some communities distributed gauze masks that were largely ineffective against the virus.

Hospitals offered little beyond basic supportive care. The pandemic exposed the limits of early 20th century medicine and spurred massive investment in virology research. This scientific awakening eventually led to the first flu vaccines in the 1940s and fundamentally changed how humanity prepares for and responds to infectious disease threats.