The 1960s was a golden age for literature that challenged social norms and pushed boundaries. Book clubs across America buzzed with passionate discussions about civil rights, feminism, and counterculture themes reflected in the decade’s most influential works. Many of these groundbreaking novels continue to captivate readers today, with one particular title still igniting fierce debates whenever it appears on reading lists.

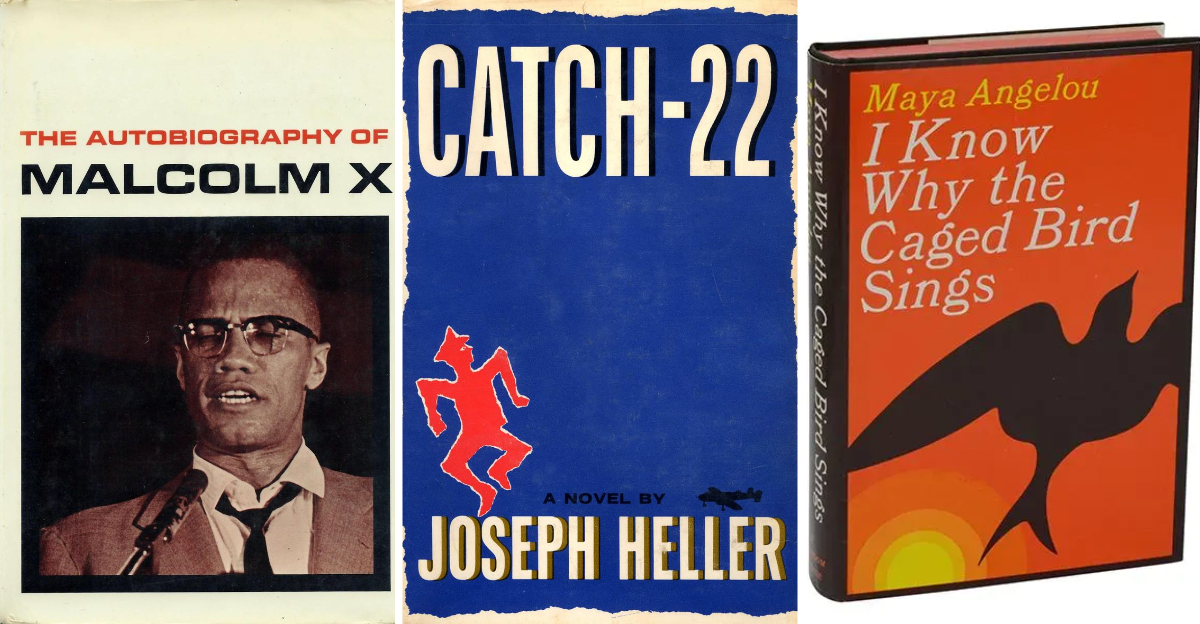

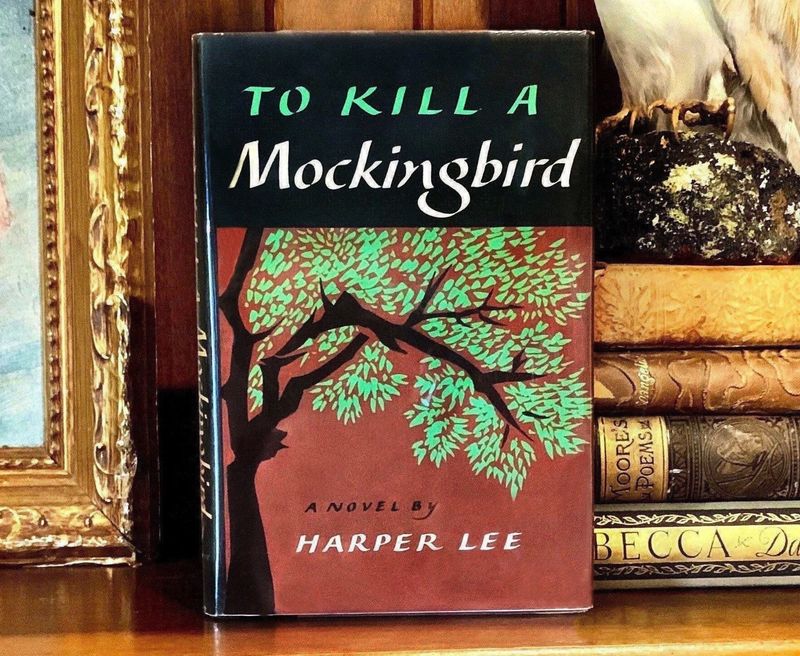

1. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Published in 1960, this Pulitzer Prize-winning novel immediately captured America’s conscience. Scout Finch’s coming-of-age story unfolds against the backdrop of racial injustice in Alabama, where her father Atticus defends a Black man falsely accused of rape.

The book’s unflinching examination of prejudice, courage, and morality made it an instant classic. Schools embraced it as required reading, though some parents challenged its frank portrayal of racism and use of period-appropriate language.

Today, it remains the most debated ’60s novel in book clubs, with discussions often centering on whether its approach to race relations feels dated or timeless in our current social climate.

2. Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

Captain Yossarian’s desperate attempts to escape the madness of war created a new term for impossible situations. Heller’s darkly comic masterpiece exposed the absurdity of military bureaucracy through a non-linear narrative that mirrored the chaos it described.

Book clubs in the ’60s grappled with its unconventional structure and cynical view of authority. The novel’s anti-war message resonated deeply during Vietnam, making it required reading among college students and activists.

Readers still marvel at how Heller balanced humor with profound commentary on the dehumanizing effects of war. The term “catch-22” permanently entered our vocabulary, describing the perfect no-win scenarios we all face.

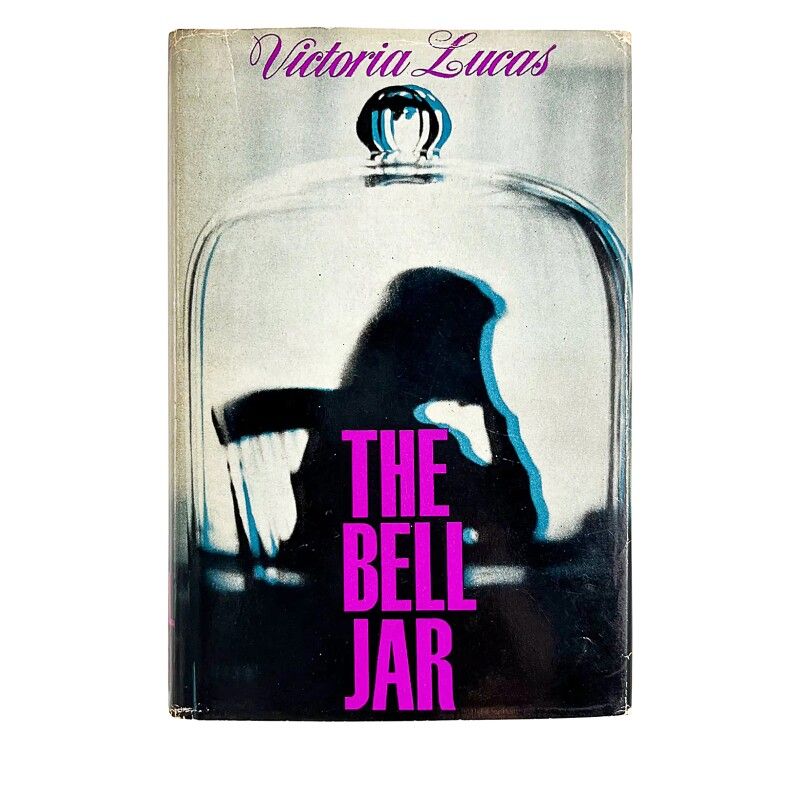

3. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

Originally published under a pseudonym in 1963, Plath’s semi-autobiographical novel chronicled a young woman’s descent into mental illness. Esther Greenwood’s struggle with depression, attempted suicide, and recovery mirrored Plath’s own experiences, making the reading experience all the more haunting.

Female readers especially connected with the protagonist’s frustration at society’s limited options for women. Book clubs found themselves discussing topics previously considered taboo: mental health, electroshock therapy, and women’s ambitions beyond motherhood.

Plath’s suicide shortly after publication added a tragic dimension that continues to color interpretations of this raw, unflinching portrayal of a brilliant mind fighting against both internal demons and external constraints.

4. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey

Randle McMurphy’s rebellion against Nurse Ratched captivated readers when published in 1962. Kesey’s experience working in a mental hospital informed this powerful exploration of individuality versus institutional control, narrated by the seemingly mute Chief Bromden.

Book clubs debated the novel’s portrayal of mental illness treatment and its broader metaphor for conformity in American society. The counterculture movement embraced it as a manifesto against authority and social conditioning.

Many readers were shocked by its unflinching depiction of lobotomy and electroshock therapy. The 1975 film adaptation starring Jack Nicholson introduced the story to an even wider audience, but book club members still insist the novel’s psychological depth surpasses even this acclaimed movie.

5. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

True crime as literature began with this 1966 “non-fiction novel” detailing the senseless murder of the Clutter family in rural Kansas. Capote spent years researching, interviewing townspeople and the killers themselves, creating an intimate portrait of both victims and perpetrators.

Book clubs were fascinated by the ethical questions raised by Capote’s methods. His close relationship with murderer Perry Smith sparked debates about journalistic boundaries and objectivity.

Readers found themselves uncomfortably sympathetic to the killers while mourning the innocent family. The book’s legacy extends beyond literature—it revolutionized crime reporting and spawned countless imitators, though few have matched Capote’s psychological insight and lyrical prose in examining the darkest corners of American life.

6. Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

“So it goes” became the mantra of a generation after Vonnegut’s 1969 masterpiece about Billy Pilgrim, who becomes “unstuck in time” after surviving the firebombing of Dresden. The novel’s blend of science fiction, autobiography, and anti-war sentiment created something entirely new in American literature.

Book clubs engaged with its innovative structure, dark humor, and profound questions about fate and free will. Many readers found comfort in Vonnegut’s matter-of-fact approach to death and suffering.

The book was frequently banned for its language, sexual content, and supposedly anti-American sentiments. This only increased its popularity among young readers, who passed dog-eared copies among friends while discussing its famous opening line: “All this happened, more or less.”

7. The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan

Suburban housewives across America secretly nodded in recognition when Friedan named “the problem that has no name” in 1963. This groundbreaking work identified the widespread unhappiness among educated women limited to domestic roles, challenging the post-war ideal of feminine fulfillment through homemaking.

Women’s book clubs became consciousness-raising groups as members shared their own experiences of dissatisfaction. Many reported feeling simultaneously relieved and angry to discover their private frustrations were actually part of a larger social pattern.

Male readers often reacted defensively, while some women criticized Friedan for focusing primarily on middle-class white women’s concerns. Despite these limitations, the book launched second-wave feminism and forever changed conversations about women’s roles in society.

8. Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann

Sex, pills, and Hollywood scandals made this 1966 novel a guilty pleasure that women secretly passed between themselves. Following three young women seeking fame in New York and Hollywood, it exposed the dark side of glamour as they turned to “dolls” (pills) to cope with life’s pressures.

Book clubs officially discussed its literary merits (or lack thereof) while privately relating to its raw portrayal of female ambition and disappointment. Critics dismissed it as trashy, but readers couldn’t get enough of its brutal honesty about women’s struggles with aging, career, and relationships.

Despite being panned by reviewers, it became one of the best-selling books of all time. Modern readers appreciate its ahead-of-its-time frankness about addiction, plastic surgery, and the entertainment industry’s exploitation of women.

9. The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Malcolm X’s personal transformation from criminal to controversial civil rights leader captivated readers across racial lines when published posthumously in 1965. His collaboration with Alex Haley produced a riveting account of his journey through prison, religious conversion, and evolving views on racial justice.

White book club members often found their assumptions challenged by his unfiltered descriptions of racism in America. Black readers debated his changing perspectives, particularly his split from the Nation of Islam and growing openness to coalition-building after his pilgrimage to Mecca.

The autobiography remains powerful for its honesty about personal growth and redemption. Malcolm’s assassination shortly before publication lent additional weight to his final message of potential reconciliation, making this work a cornerstone of civil rights literature.

10. Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

Few books can claim to have launched an entire movement, but Carson’s 1962 exposé on pesticide dangers did exactly that. Her meticulous research revealed how chemicals like DDT were poisoning wildlife, contaminating food chains, and threatening human health.

Book clubs found themselves discussing ecology—a new concept for many Americans. Carson’s lyrical prose made scientific concepts accessible, allowing readers to understand complex environmental relationships.

Chemical companies launched vicious attacks on Carson personally, but the public sided with her evidence. President Kennedy ordered an investigation based on her findings, eventually leading to the creation of the EPA and the modern environmental movement. This book demonstrated how carefully researched writing could literally change government policy and public consciousness.

11. The Group by Mary McCarthy

Eight Vassar graduates navigating love, career, and societal expectations scandalized and enthralled readers in 1963. McCarthy’s frank treatment of contraception, breastfeeding struggles, and female sexuality broke taboos about what could be discussed in “respectable” fiction.

Women’s book clubs devoured its realistic portrayal of female friendship and the compromises women made between traditional roles and personal ambition. The characters’ varying paths—from traditional marriage to career focus—offered readers different models of womanhood rarely seen in literature.

Men often dismissed it as gossip in print, missing its sharp social critique. Today, it’s recognized as a forerunner to modern feminist fiction, with its clear-eyed examination of how even privileged, educated women faced significant barriers to self-determination in mid-century America.

12. Dune by Frank Herbert

Science fiction transcended its pulp origins with Herbert’s 1965 epic about power, religion, and ecology on the desert planet Arrakis. Paul Atreides’ journey from privileged heir to messianic revolutionary challenged readers with its complex political themes and ecological warnings.

Book clubs appreciated its world-building depth and philosophical richness. Discussions often centered on its prescient environmental concerns, exploration of religious manipulation, and critique of hero worship.

Women particularly noted the prominence of the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, whose subtle power operated alongside the more obvious male authority structures. Herbert’s blend of adventure with serious ideas about resource scarcity, religious fanaticism, and genetic manipulation created a template for thoughtful speculative fiction that continues to influence writers and filmmakers today.

13. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe

Journalist Wolfe captured the psychedelic adventures of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters in this 1968 masterpiece of New Journalism. His immersive, subjective reporting style mirrored the consciousness-expanding experiences he documented, complete with unusual punctuation and typographical experiments.

Book club members debated whether Wolfe glorified or simply documented drug culture. Some readers were fascinated by descriptions of LSD experiences, while others focused on the book’s exploration of community-building and rejection of conventional society.

Wolfe’s vivid prose brought readers along for the ride on the Pranksters’ psychedelic bus “Further.” His account preserved a pivotal moment in counterculture history, connecting the Beat Generation to the hippie movement while demonstrating how literary techniques could be applied to factual reporting.

14. The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon

Oedipa Maas’s quest to unravel a possible centuries-old postal conspiracy left readers simultaneously confused and exhilarated in 1966. Pynchon’s slim novel packed extraordinary density into its paranoid plot, becoming the perfect book for intellectually adventurous book clubs.

Groups spent hours debating whether the Tristero conspiracy actually existed or was merely Oedipa’s delusion. The novel’s ambiguous ending frustrated some readers while delighting others with its refusal to provide easy answers.

College students particularly embraced its countercultural sensibility and playful experimentation with language. Pynchon’s blend of high and low culture, historical references, and scientific concepts created a new template for postmodern fiction that continues to influence writers today, while his themes of information overload and pattern-seeking feel increasingly relevant in our digital age.

15. Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth

Alexander Portnoy’s explicit confessions about his sexual obsessions and Jewish-American identity shocked readers in 1969. Structured as a monologue to his psychoanalyst, Roth’s novel broke boundaries with its frank treatment of masturbation, sexual fantasy, and family dynamics.

Book clubs divided sharply along generational lines. Older readers often found it obscene, while younger members defended its literary merits and psychological insights. Jewish communities particularly debated whether Roth had betrayed his heritage by airing “dirty laundry” or created an honest portrayal of cultural assimilation pressures.

The novel became a touchstone in discussions about obscenity in literature. Despite controversy, its humor and examination of guilt, desire, and identity established Roth as a major American writer and opened doors for more explicit explorations of sexuality in mainstream fiction.

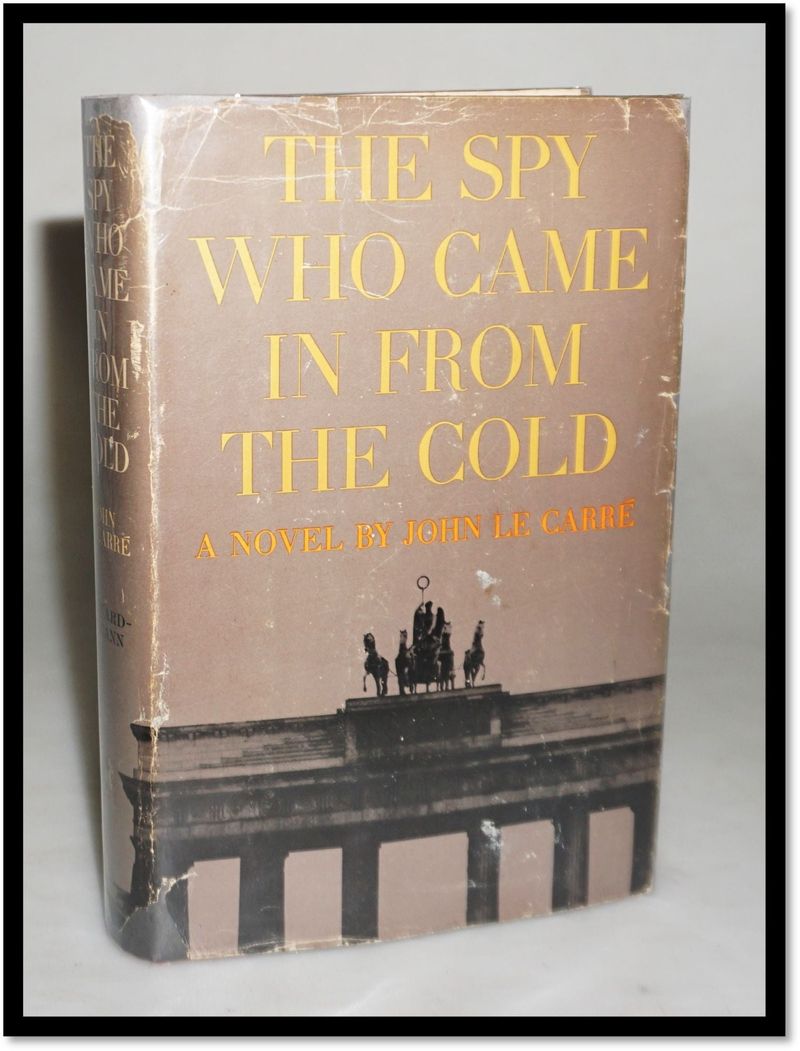

16. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John le Carré

Alec Leamas’s final mission revealed the moral bankruptcy of Cold War espionage in this 1963 thriller that revolutionized the spy genre. Le Carré’s gritty, realistic portrayal of intelligence work contrasted sharply with James Bond’s glamorous adventures, showing spies as morally compromised pawns in cynical political games.

Book clubs appreciated its literary quality and complex ethical questions. Readers debated whether the novel was anti-Western or simply anti-ideological, with its suggestion that both sides in the Cold War used equally ruthless methods.

Le Carré’s insider knowledge from his own intelligence career lent authenticity to his portrayal of the spy world’s gray morality. The novel’s bleak ending challenged the triumphalist Cold War narrative, suggesting that ordinary people were sacrificed for abstract geopolitical goals that ultimately served only those in power.

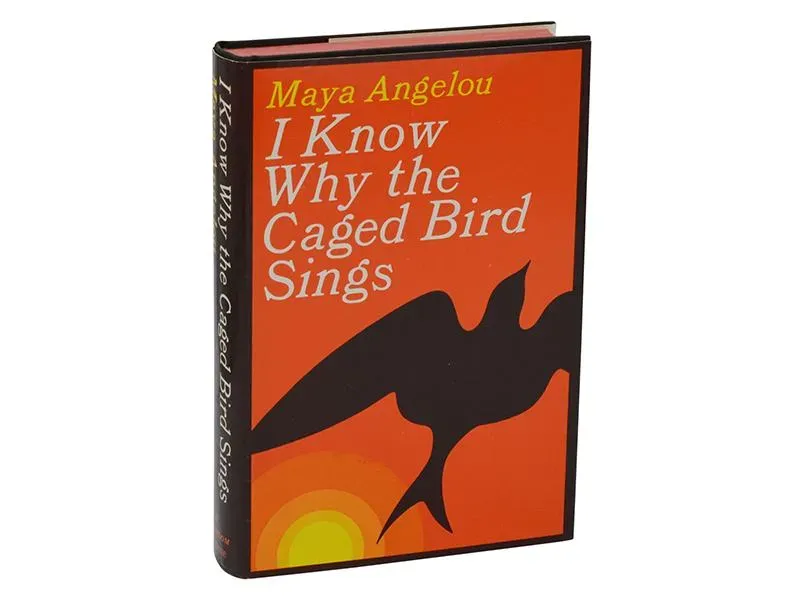

17. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Published in 1969, Angelou’s lyrical memoir of her childhood in the Jim Crow South brought previously marginalized experiences to mainstream readers. Her unflinching account of trauma, including sexual abuse and racism, alongside moments of joy and resilience, created an unforgettable portrait of growing up Black in America.

Book clubs found themselves discussing racism, sexual violence, and literacy as liberation in new ways. White readers often reported being profoundly moved by Angelou’s vivid depiction of experiences they had never encountered in literature before.

The book’s poetic language elevated personal testimony to literary art. Schools embraced it as required reading, though some parents challenged its inclusion due to its frank treatment of sexual abuse. Angelou’s memoir opened doors for other writers of color and established autobiography as a vehicle for exploring larger social issues.