Books tell us more than just what happened—they show us how events felt to real people. While historians record dates and facts, great writers reveal the heart behind the headlines. They put us in the shoes of Americans from all walks of life, helping us understand hopes, fears, and dreams across generations. These storytellers have captured the true essence of America in ways no textbook ever could.

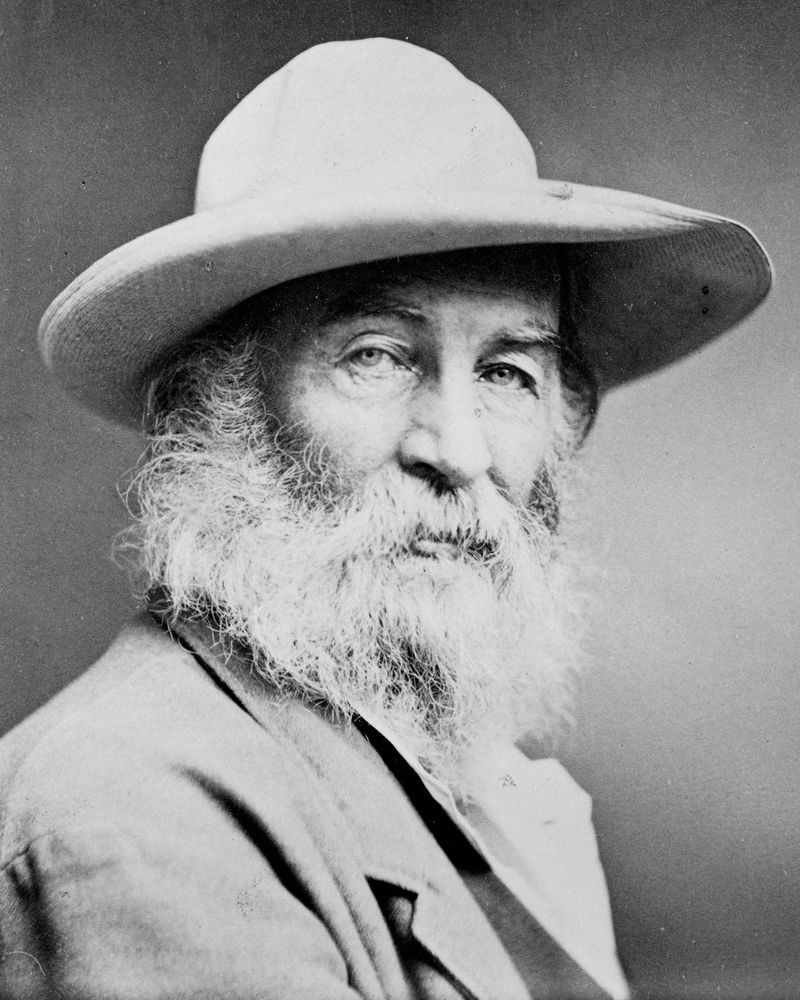

1. Walt Whitman: Democracy’s Poetic Voice

Long before Instagram and Twitter, Walt Whitman was America’s original self-promoter, anonymously publishing glowing reviews of his own revolutionary work. His masterpiece Leaves of Grass celebrated everyday Americans with passionate, free-flowing lines that broke all the stuffy poetry rules of his time.

Whitman wandered America’s cities and countryside, absorbing the voices of farmers, nurses, and laborers. During the Civil War, he worked as a battlefield nurse, witnessing both the country’s deepest divisions and the common humanity of wounded soldiers from both sides.

His words embraced democracy, sexuality, and spiritual freedom when such topics shocked polite society. “I am large, I contain multitudes,” he wrote—just like the America he loved.

2. Toni Morrison: Unearthing Buried Truths

Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison refused to sugarcoat America’s painful racial history. Her novel Beloved was inspired by a true story of an enslaved mother who killed her own child rather than let her be returned to slavery—a horror Morrison believed Americans needed to confront.

Growing up in Ohio during segregation, Morrison absorbed the stories of her family and community. These tales later became the foundation for her powerful novels exploring Black identity, motherhood, and the lasting scars of America’s original sin.

Morrison’s genius lay in making readers feel history rather than just learn it. Through magical realism and unforgettable characters, she forced America to remember what it wanted to forget.

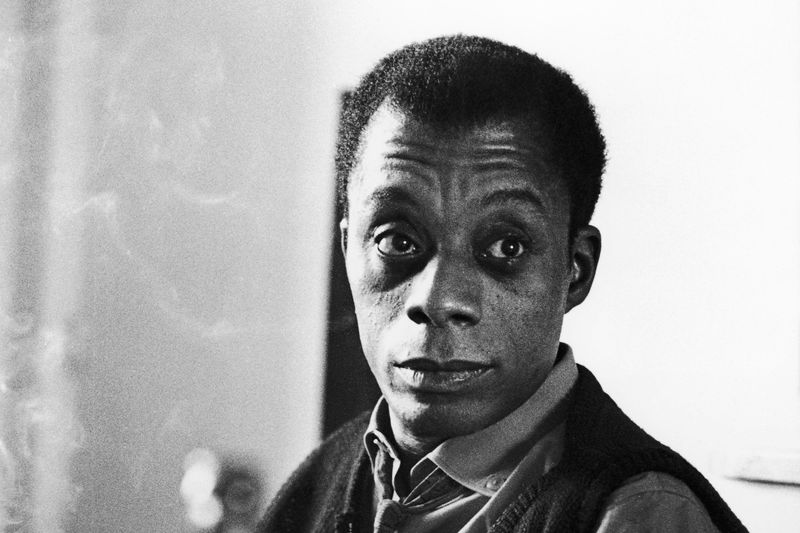

3. James Baldwin: Prophet of American Reckoning

When James Baldwin spoke, America listened—even when his words stung. After fleeing to Paris to escape American racism, this gay Black writer returned to join the Civil Rights Movement, bringing a unique perspective on what it meant to be doubly marginalized in his homeland.

Baldwin’s essays like “The Fire Next Time” predicted the racial unrest of the 1960s with eerie accuracy. His novel Giovanni’s Room boldly explored sexuality decades before gay rights became a mainstream cause.

Unlike many angry young writers, Baldwin’s work contained as much love as rage. “I love America more than any other country in the world,” he once wrote, “and exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

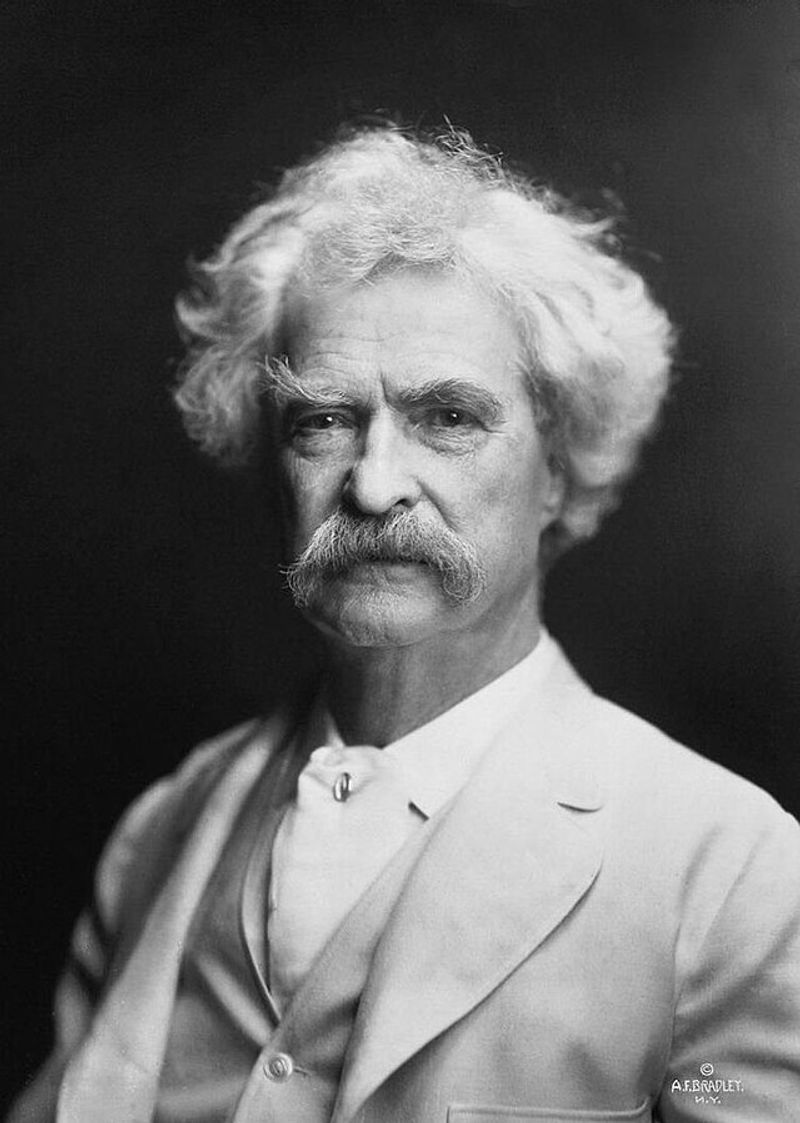

4. Mark Twain: The Satirist Who Saw Through America

Samuel Clemens—better known as Mark Twain—witnessed America transform from a rural frontier to an industrial powerhouse. Born when slavery was legal and dying after the first automobiles hit the road, his life spanned America’s most dramatic changes.

His masterpiece Adventures of Huckleberry Finn used a boy’s simple voice to expose complex hypocrisies. The friendship between Huck and Jim challenged readers to see the humanity in those society deemed inferior.

Behind Twain’s famous mustache and white suit lurked a dark humorist who grew increasingly cynical about human nature. Yet his biting satire came from disappointment in what America could be versus what it was—the ultimate act of patriotism.

5. Zora Neale Hurston: Collector of Black Southern Soul

Armed with a notebook and a pistol, Zora Neale Hurston traveled dirt roads across the Deep South in the 1920s. As both a trained anthropologist and talented novelist, she preserved Black folk tales, songs, and speech patterns that might otherwise have vanished forever.

Her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God shocked readers with its frank portrayal of a Black woman’s search for love and identity. The book’s rich dialogue captured the poetry of everyday Black speech at a time when most white authors reduced it to crude stereotypes.

Hurston died poor and was buried in an unmarked grave. Writer Alice Walker later rescued Hurston’s legacy from obscurity, recognizing her as one of America’s most authentic cultural voices.

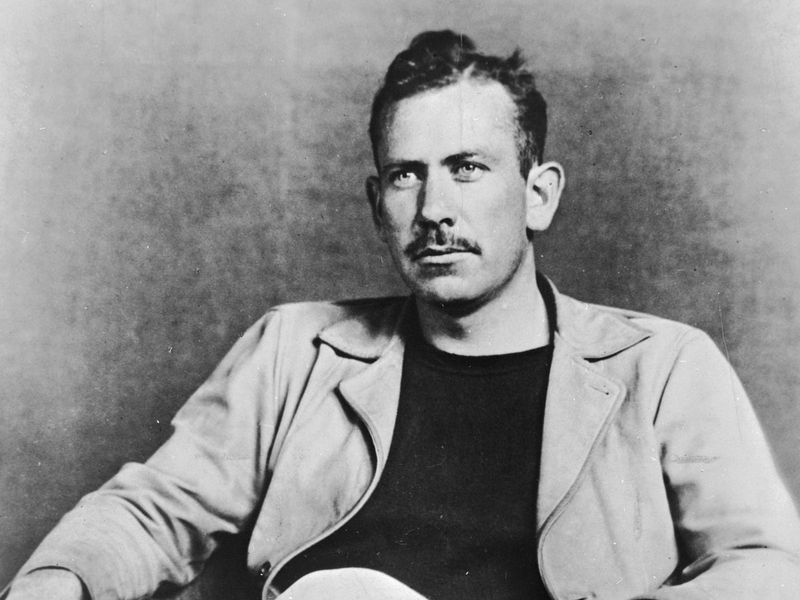

6. John Steinbeck: Chronicler of America’s Forgotten People

Riding in pickup trucks with migrant workers and living in their camps, John Steinbeck gathered material for what would become The Grapes of Wrath. This groundbreaking novel showed Americans the human cost of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression through the eyes of the Joad family.

Steinbeck’s straightforward prose carried the dignity of ordinary people facing extraordinary hardship. His characters weren’t statistics—they were fishermen, farm workers, and shopkeepers struggling to survive while holding onto their humanity.

Called a communist for exposing economic injustice, Steinbeck maintained he was simply telling the truth about America’s underclass. His work reminds us that national history isn’t just about presidents and generals—it’s about everyone.

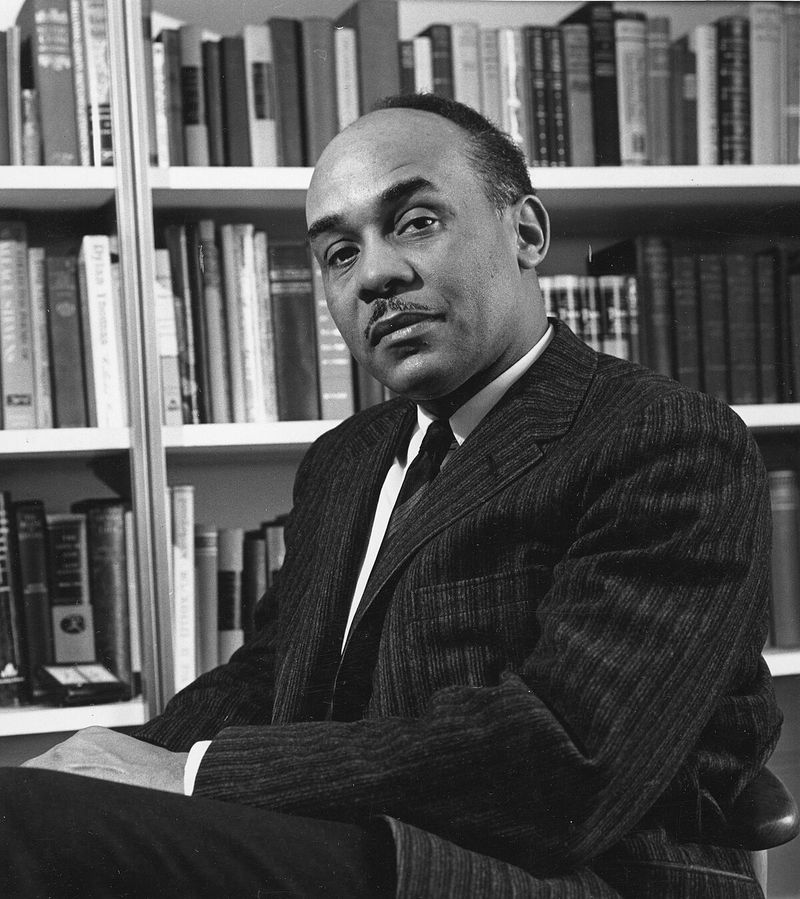

7. Ralph Ellison: Illuminating American Invisibility

“I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” With this powerful opening line, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man introduced readers to a nameless Black narrator navigating an America determined to look through him rather than at him.

Ellison drew from his experiences in depression-era Harlem and as a student at a Black college in the segregated South. His novel follows a young man’s journey through various American communities—Black and white, communist and capitalist, Northern and Southern—finding himself unseen in each.

Unlike many protest novels of his era, Ellison’s masterpiece transcends simple political messages. It’s about the universal human struggle for identity in a world that assigns labels rather than seeing individuals.

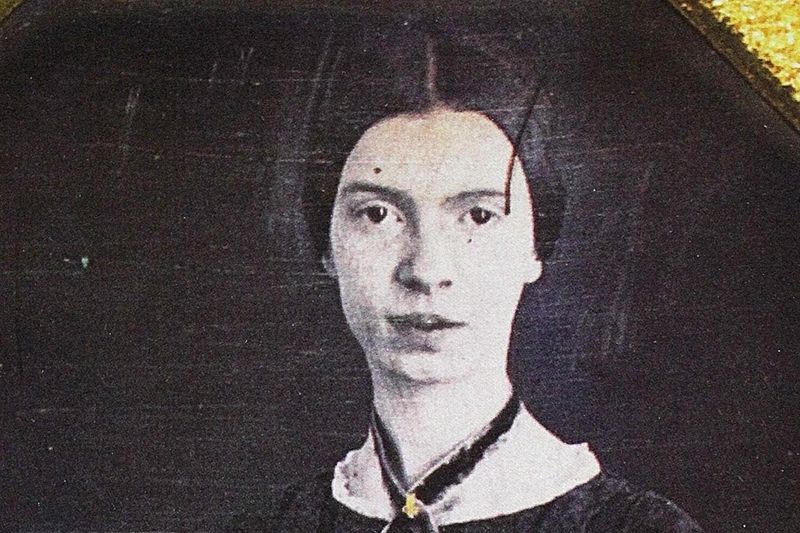

8. Emily Dickinson: Recluse Who Saw America’s Inner Life

While Civil War battles raged across America, Emily Dickinson fought private wars within her bedroom walls. This reclusive poet rarely left her family home in Amherst, Massachusetts, yet her short, electrifying poems captured universal human experiences with startling precision.

Dickinson wrote nearly 1,800 poems but published only about ten during her lifetime. Her unconventional punctuation—especially her famous dashes—created breathless rhythms that mirrored her revolutionary thinking about death, nature, and immortality.

Though physically isolated, Dickinson’s mind roamed freely through America’s emotional landscape. Her work reveals the rich interior lives of 19th-century Americans, especially women whose thoughts and feelings rarely appeared in official histories.

9. F. Scott Fitzgerald: Exposing the American Dream’s Dark Side

The glittering parties, fast cars, and flowing champagne of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels masked a deeper critique of American materialism. His masterpiece The Great Gatsby used the tragic figure of Jay Gatsby to explore how the pursuit of wealth corrupts the American promise of reinvention.

Fitzgerald lived his own version of the American Dream, rising from middle-class Minnesota to Princeton and literary fame. His marriage to Alabama socialite Zelda Sayre gave him insider access to the extravagant world of 1920s wealth that he would immortalize—and criticize—in his fiction.

As the Jazz Age collapsed into the Great Depression, Fitzgerald’s work revealed how quickly American dreams can turn to dust. His novels remain perfect time capsules of a nation drunk on prosperity before the inevitable hangover.

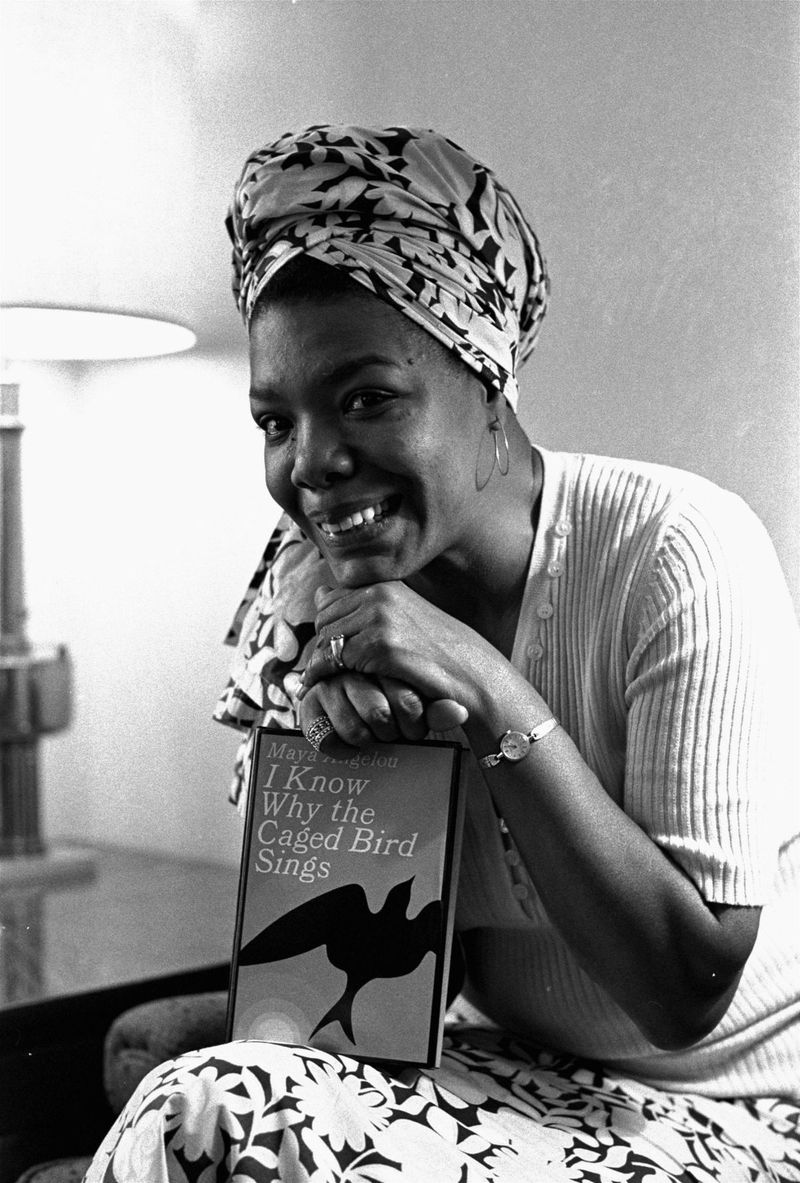

10. Maya Angelou: Voice of Survival and Celebration

Before becoming a literary icon, Maya Angelou lived many American lives—as a San Francisco streetcar conductor, Calypso dancer, civil rights activist, and single mother. Her groundbreaking memoir I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings transformed personal trauma into art, describing childhood sexual abuse with unflinching honesty.

Angelou’s deep, melodic voice carried the rhythm of African American oral tradition. Her poetry mixed everyday speech with powerful imagery, making complex ideas about identity and freedom accessible to readers of all backgrounds.

Having worked alongside both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., Angelou brought firsthand experience of America’s civil rights struggle to her writing. Her presence at Bill Clinton’s 1993 inauguration, reading “On the Pulse of Morning,” symbolized her role as America’s poetic conscience.

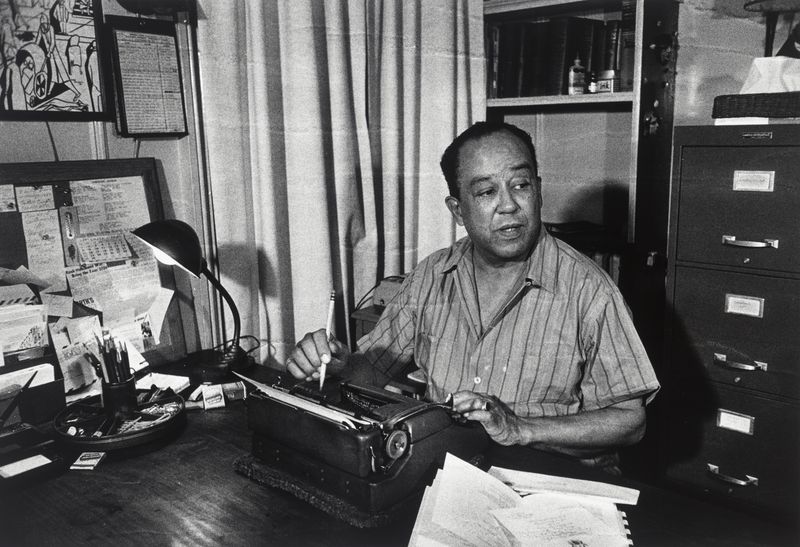

11. Langston Hughes: Poet of Harlem’s Renaissance

Langston Hughes carried a small notebook everywhere, jotting down the language of Black America he heard in jazz clubs, churches, and street corners. His poems like “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” and “Harlem” captured both the deep historical roots and contemporary struggles of African Americans.

Hughes deliberately wrote in simple, accessible language. “I have never been one of these poets who went in for intricate and obscure meanings,” he explained, believing poetry should speak directly to ordinary people about their lives.

As a central figure in the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, Hughes helped create a new Black artistic identity. His work balanced unflinching portrayals of racism with celebrations of Black joy, music, and resilience—showing America the full humanity of people often reduced to stereotypes.

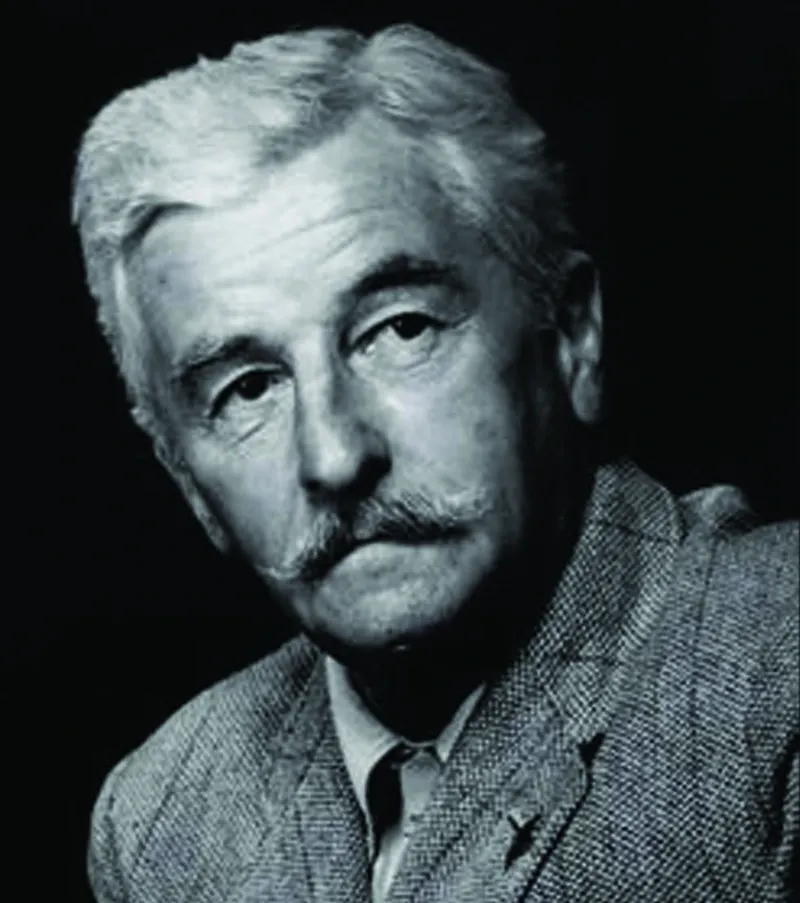

12. William Faulkner: Excavator of Southern Memory

William Faulkner rarely left his small Mississippi hometown, yet created an entire fictional universe within it. His imaginary Yoknapatawpha County became a stage where the South’s haunted past collided with its troubled present, revealing America’s unhealed wounds.

Faulkner’s novels like Absalom, Absalom! feature sprawling sentences and multiple narrators, mirroring how memory works—fragmented, contradictory, and emotionally charged. His characters carry the weight of history, struggling with the legacy of slavery and Civil War defeat.

Though sometimes dismissed as a regional writer, Faulkner addressed universal human questions. His 1949 Nobel Prize speech famously declared that writers must focus on “the old verities and truths of the heart…love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice.”

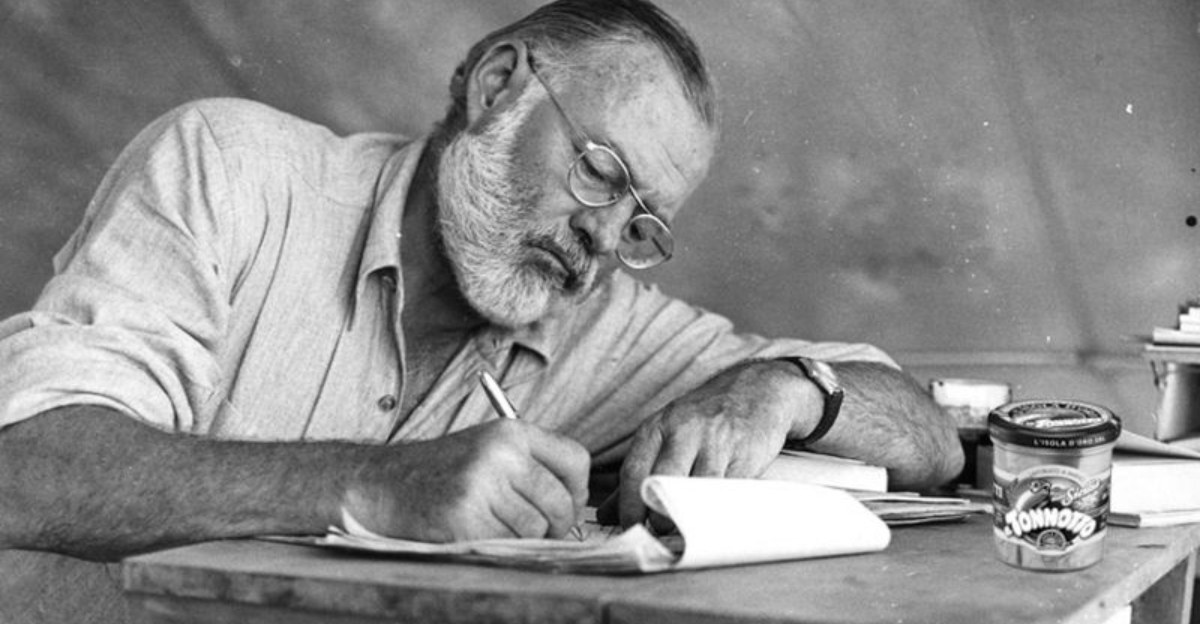

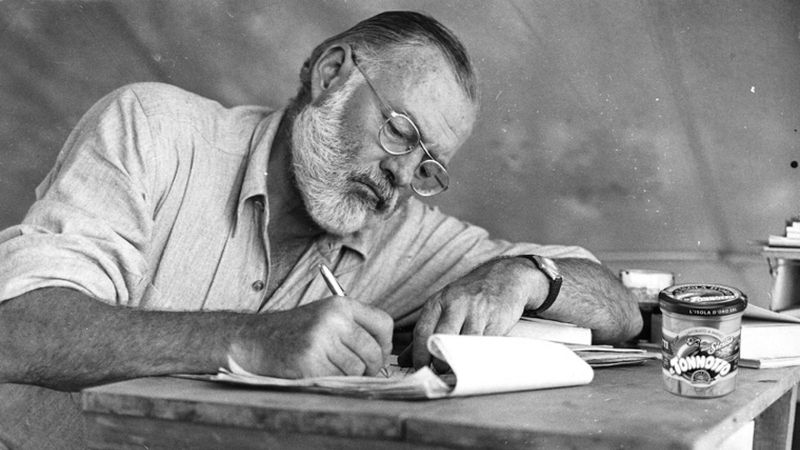

13. Ernest Hemingway: Masculine America in Sparse Prose

Ernest Hemingway stripped American writing down to its bare essentials. His famous “iceberg theory” suggested good writing should reveal only the surface, with deeper meaning hidden beneath simple words—just as most of an iceberg remains underwater.

Wounded as an ambulance driver in World War I, Hemingway became the voice of America’s “Lost Generation.” His characters—bullfighters, soldiers, and hunters—faced death with stoic courage, embodying a particular vision of American masculinity that still influences our culture.

Behind his macho public image, Hemingway’s work revealed vulnerability and fear. His novel The Old Man and the Sea showed how Americans define themselves through struggle, finding dignity even in defeat—perhaps his most enduring contribution to our national character.

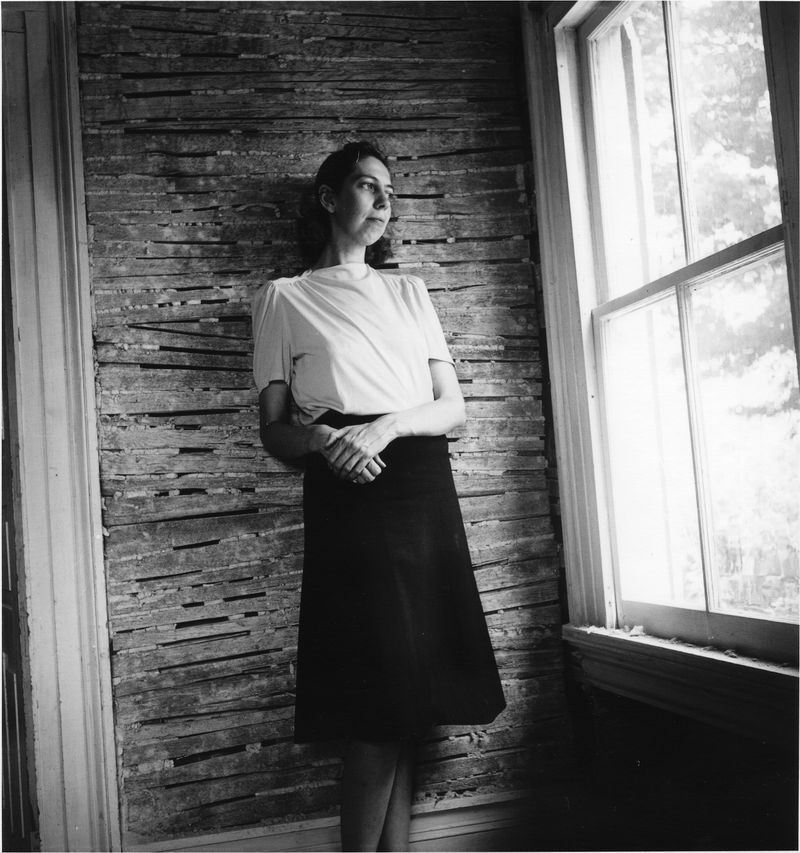

14. Flannery O’Connor: Gothic Storyteller of Grace and Grotesquery

From her peacock-filled farm in Georgia, Flannery O’Connor created stories populated by religious fanatics, con men, and misfits. Despite battling lupus that would claim her life at 39, she produced some of America’s most startling fiction about faith and human frailty.

O’Connor’s Catholic beliefs shaped her unique vision of the American South. Her stories like “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” often end in shocking violence that represents moments of divine grace—though readers might see only the horror on first reading.

Behind her Southern Gothic style lay keen observations about America’s racial tensions and religious hypocrisy. “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it,” she once wrote—a philosophy that made her work both disturbing and profoundly honest.

15. Sherman Alexie: Modern Voice of Native America

Growing up on the Spokane Indian Reservation with hydrocephalus (“water on the brain”), Sherman Alexie found escape through books. He later transformed his experiences into stories that blend heartbreak with humor, giving voice to contemporary Native American life rarely seen in mainstream literature.

Alexie’s breakthrough collection The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven inspired the film Smoke Signals—the first major movie written, directed, and acted by Native Americans. His characters navigate between reservation life and urban settings, battling alcoholism, poverty, and cultural erasure.

Through basketball-playing poets and reservation blues bands, Alexie shows Native Americans as fully human rather than historical relics or spiritual stereotypes—an essential corrective to America’s sanitized frontier mythology.

16. Eudora Welty: Photographer of Southern Lives

Before becoming a writer, Eudora Welty captured Depression-era Mississippi as a photographer for the WPA. This visual training shows in her fiction—she describes characters and settings with a photographer’s eye for telling details.

Unlike many Southern writers obsessed with the Civil War, Welty focused on the quiet drama of everyday life. Her stories like “Why I Live at the P.O.” reveal how family relationships and small-town gossip shape individual lives more than grand historical events.

Welty rarely left her mother’s Jackson, Mississippi home, yet her work transcends regional labels. Her characters—eccentric aunts, traveling salesmen, and small-town dreamers—represent universal human experiences of love, loss, and belonging, showing how America’s soul lives in its ordinary corners.

17. Joan Didion: Cool-Eyed Witness to American Breakdown

Joan Didion arrived in California just as the 1960s counterculture was collapsing. Her essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem documented this unraveling with clinical precision, from Haight-Ashbury drug casualties to Hollywood’s empty glamour.

Tiny in stature but massive in influence, Didion created a new kind of American essay. Her detached, observational style revealed national anxieties through personal experience, making her the perfect chronicler of an era when shared narratives were breaking apart.

After decades writing about political and cultural disorder, Didion turned her unflinching gaze on personal tragedy in The Year of Magical Thinking. This memoir about her husband’s sudden death showed how even the most analytical mind breaks down when confronting grief—much like America itself during its moments of crisis.

18. Alice Walker: Weaver of Purple Prose and Politics

Alice Walker made history as the first Black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction with The Color Purple. This epistolary novel unflinchingly portrays domestic violence, sexual abuse, and racism while ultimately affirming the healing power of sisterhood and self-expression.

Raised in rural Georgia by sharecropper parents, Walker drew on her own experiences of poverty and racism. She later became an activist in the Civil Rights Movement, where she met her future husband—a white Jewish lawyer at a time when interracial marriage was still illegal in many states.

Walker coined the term “womanism” to describe Black feminism rooted in African American women’s unique experiences. Her writing celebrates the creativity, spirituality, and resilience of Black women whose stories had been largely absent from American literature.

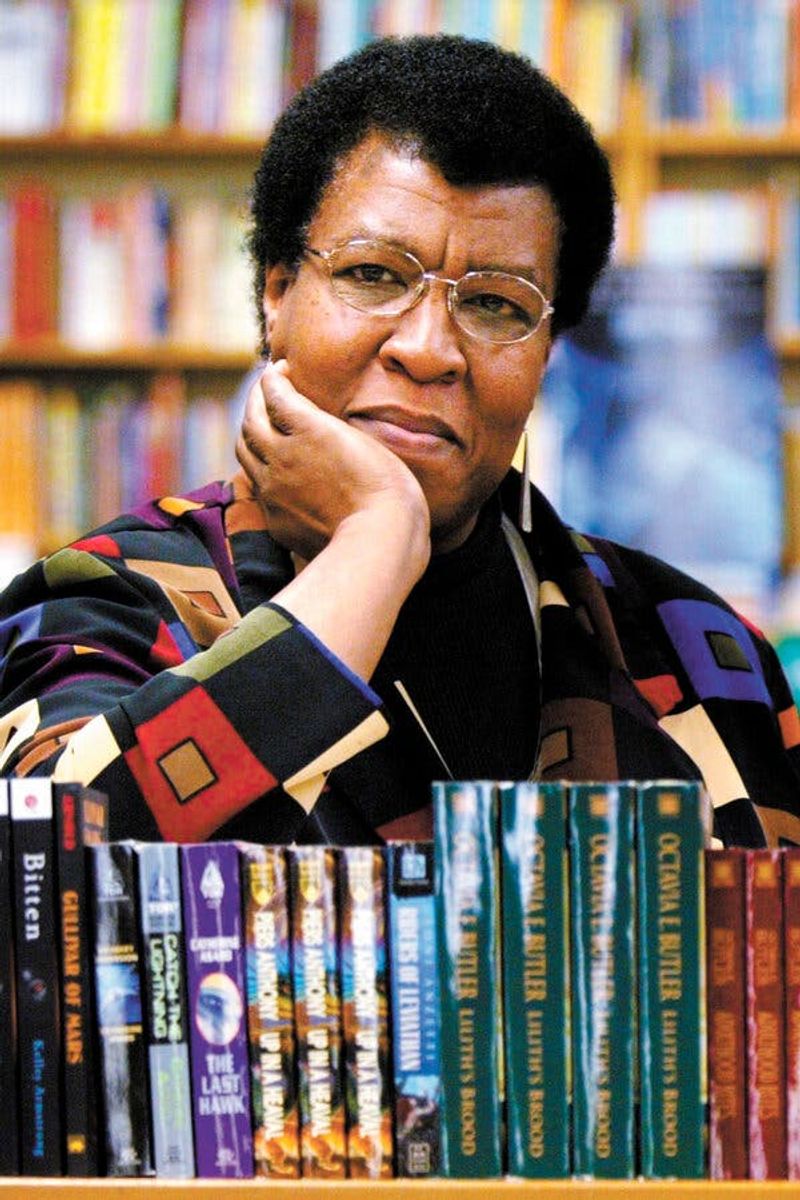

19. Octavia Butler: Prophet of American Futures

Octavia Butler transformed science fiction from space cowboys to serious social commentary. As a Black woman in a genre dominated by white men, she created futures where race, gender, and power are explored through thrilling stories of time travel, alien encounters, and post-apocalyptic societies.

Her novel Kindred sends a modern Black woman back to a plantation where she meets her enslaved ancestors. This brilliant device forces readers to confront slavery not as distant history but as living trauma that shapes contemporary America.

Butler’s Parable series eerily predicted climate disasters, wealth inequality, and even a presidential candidate promising to “make America great again”—decades before these became reality. Her work reminds us that understanding America’s future requires honestly facing its past.

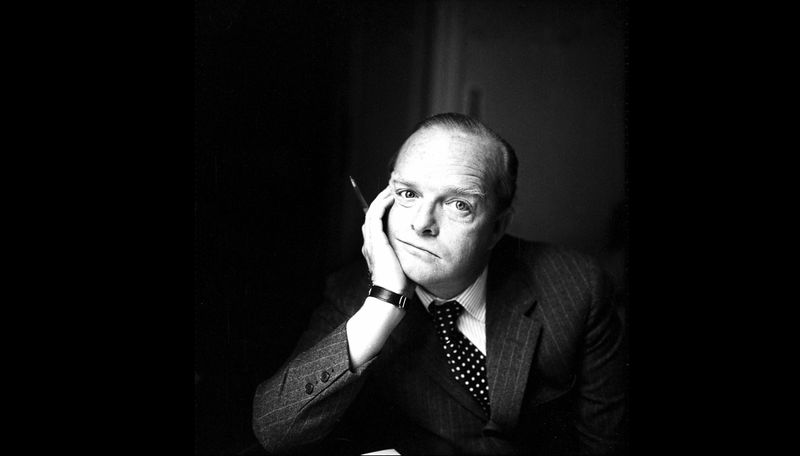

20. Truman Capote: Creator of America’s True Crime Obsession

Standing just 5’3″ with a distinctive high-pitched voice, Truman Capote might have seemed an unlikely literary giant. Yet this openly gay writer from rural Alabama revolutionized American literature with In Cold Blood, creating the “non-fiction novel” that blended journalism with narrative techniques.

Capote spent six years investigating the brutal murder of a Kansas farm family. He conducted over 8,000 pages of interviews, developing relationships with the killers themselves to understand their psychology.

Beyond true crime, Capote’s semi-autobiographical fiction like Breakfast at Tiffany’s captured American social climbing and reinvention. His famous Black and White Ball in 1966 represented the height of his celebrity before alcoholism and drug abuse cut short his brilliant career—a cautionary tale about fame’s dark side.

21. Gloria Anzaldúa: Borderlands Theorist and Cultural Bridge

Gloria Anzaldúa grew up speaking Spanish in Texas schools where this was forbidden. This early experience of cultural borderlands inspired her groundbreaking book Borderlands/La Frontera, which mixes poetry, memoir, history, and theory in both English and Spanish.

As a self-described “chicana dyke-feminist,” Anzaldúa created new language for those living between cultures. Her concept of “mestiza consciousness” describes how people at the margins develop fluid identities that challenge rigid categories of race, gender, and nationality.

Anzaldúa’s work explores physical borders like the U.S.-Mexico boundary and psychological borders between languages and identities. By refusing to translate Spanish passages in her English texts, she forces monolingual readers to experience the disorientation of border crossing—a quintessentially American experience.

22. Philip Roth: Chronicler of Jewish-American Neurosis

Philip Roth turned his Newark, New Jersey childhood into literature that both celebrated and satirized Jewish-American life. His controversial breakthrough novel Portnoy’s Complaint shocked 1969 readers with its frank treatment of sexuality, religious guilt, and assimilation anxieties.

Through alter egos like Nathan Zuckerman and David Kepesh, Roth explored masculinity in crisis. His later works like American Pastoral examined how the turbulent 1960s shattered post-war suburban dreams, showing one generation’s American success story becoming another’s nightmare.

Though sometimes accused of misogyny and Jewish self-hatred, Roth’s unflinching examination of human flaws made him one of America’s most important postwar writers. His work captures the contradictions of being both insider and outsider in American culture—a universal immigrant experience.

23. Sandra Cisneros: Voice of the American Barrio

Sandra Cisneros grew up as the only daughter among six brothers in Chicago’s Mexican-American neighborhoods. This experience of gender and cultural isolation inspired her slim but mighty novel The House on Mango Street, told through the eyes of young Esperanza Cordero.

Through short, poetic vignettes, Cisneros captures the texture of barrio life—the smells, sounds, and characters of a community rarely represented in American literature. Her work explores how physical spaces shape identity, particularly for Latina girls navigating both cultural traditions and American dreams.

Cisneros writes in English sprinkled with untranslated Spanish, creating a linguistic borderland that mirrors her characters’ experiences. Her work reminds readers that American literature, like America itself, has always been enriched by voices from its margins.